In the incongruous setting of London’s Southbank, among all its heavy-duty architecture and its everyday hustle and bustle, there is a safe arbour in the concrete jungle, a quiet sanctuary of beauty and harmony where we can remember the trees. The Hayward Gallery’s surprising exhibition Among The Trees reminds us of the many ways in which we have forgotten our close arboreal connections.

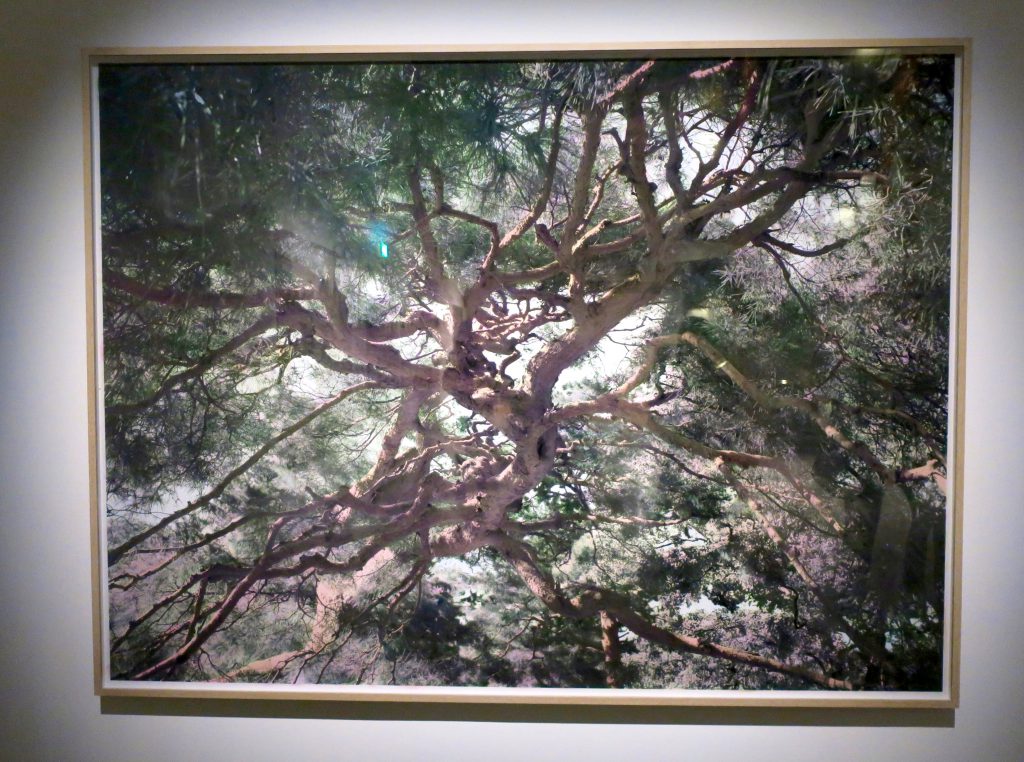

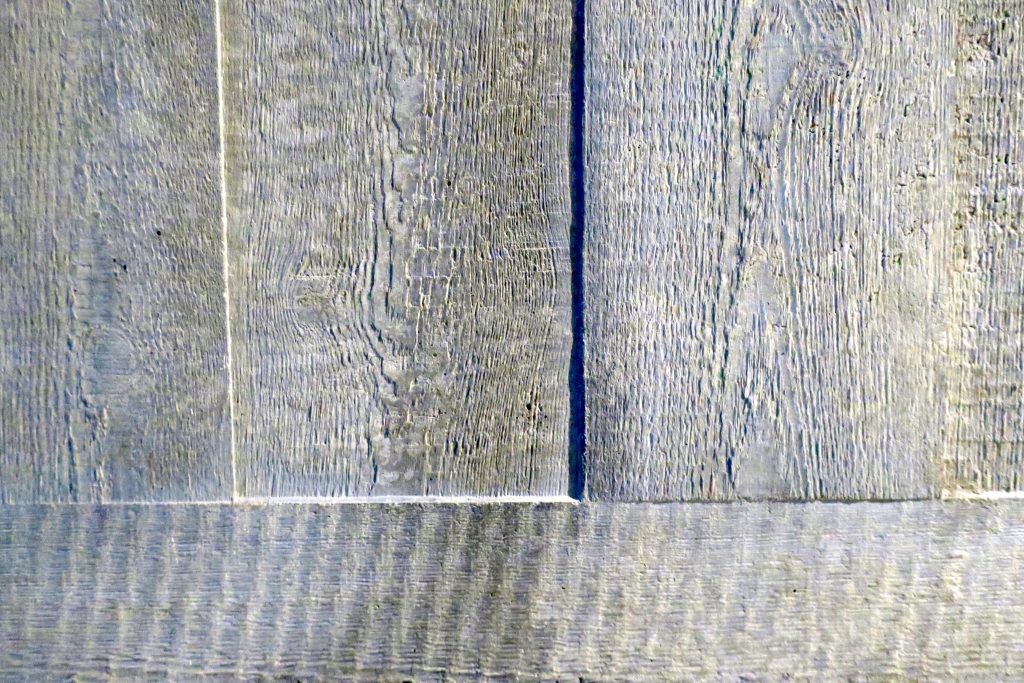

Shi Guowei: Pine 2016

painted photograph

At a time when the destruction of the world’s forests is accelerating at a record pace, ‘Among The Trees’ surveys how artists have responded to the crucial role trees play in our lives and imaginations. Spanning the past 50 years – a period that coincides with the modern environmental movement – it brings together artworks that ask us to think about trees and forests in different ways.

Environmental writer Barry Lopez has noted that ‘woods defeat the viewfinder… they cannot be framed’. Even a single bough can stretch the limits of our visual apprehension. With layers of interlacing branches and thousands upon thousands of leaves (a mature oak in summer might have well over 200,000), trees are stunningly complex and often visually confounding.

Many of the artists in this exhibition highlight those characteristics in order to engage us in an exploratory process of looking. Subverting traditional depictions of the natural world to help us see familiar forms afresh, their images also call attention to trees as interconnecting structures, chiming with recent scientific discoveries about the ‘wood wide web’ – the network of underground roots, fungi and bacteria that connect forest organisms.

Unlike classical representations of landscape, many of the works in this exhibition avoid the easy orientation offered by foreground, vista and horizon. Instead they invite us to get lost, and to experience – on some level – that uncanny thrill of momentarily losing our way in a forest, and seeing our surroundings with fresh eyes.

Thomas Struth: Paradise 11, Xi Shuang Banna, Yunnan Province, China 1999

chromogenic print

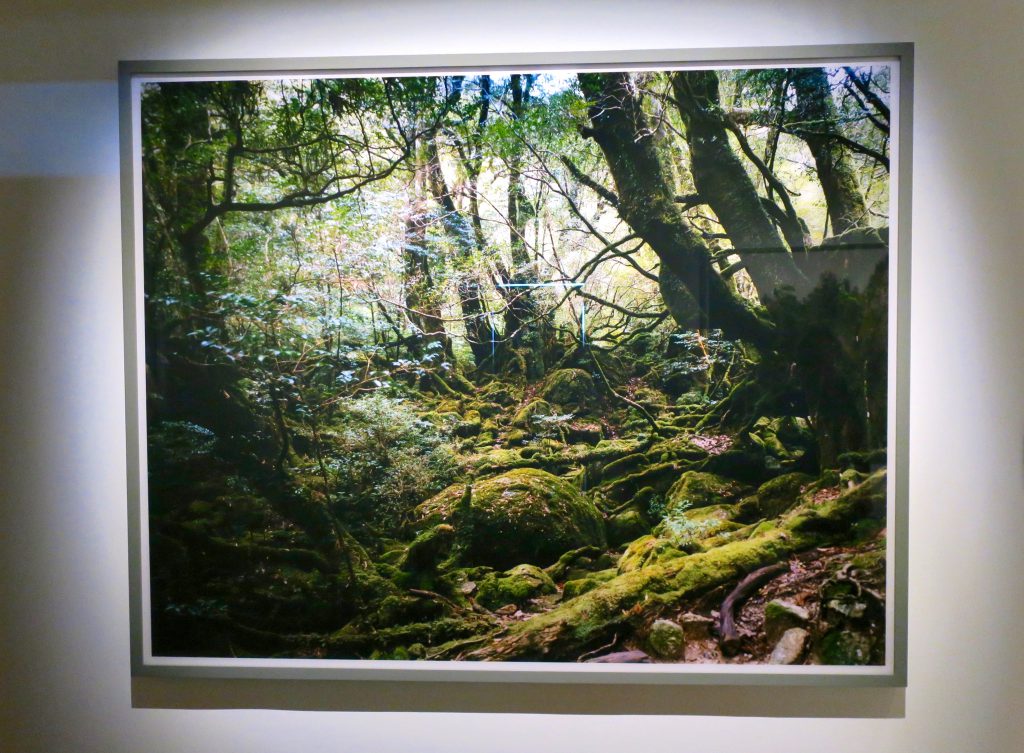

Thomas Struth: Paradise 13, Yakushima, Japan 1999

chromogenic print

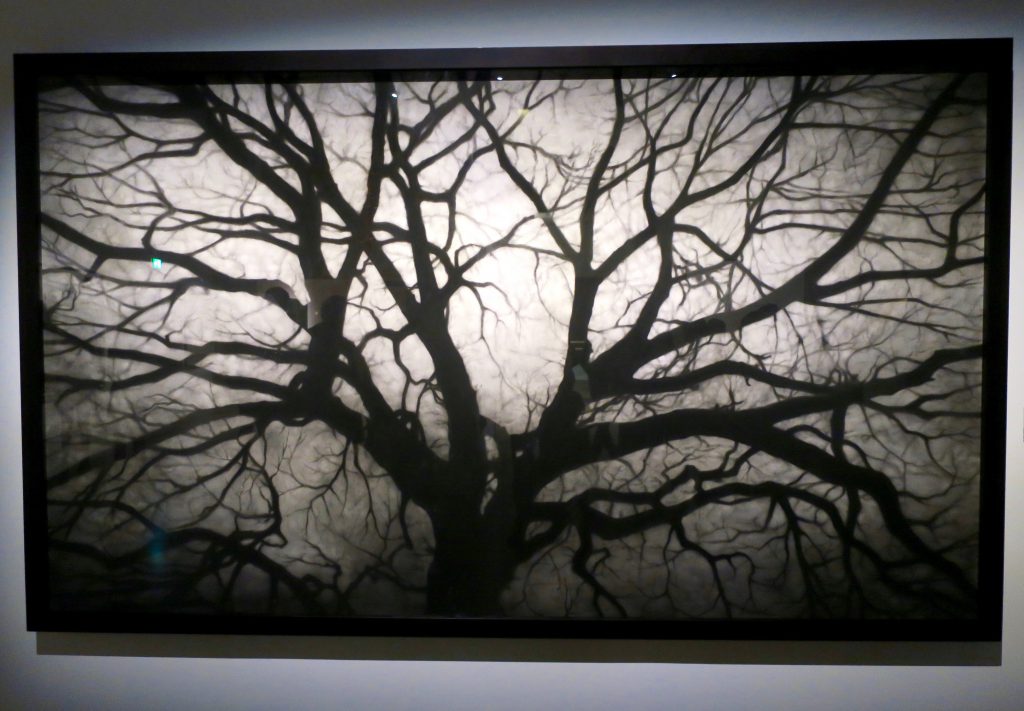

Robert Longo: Untitled (Sleepy Hollow) 2014

charcoal on mounted paper

Toba Khedoori: Untitled 2018

oil, graphite and wax on paper

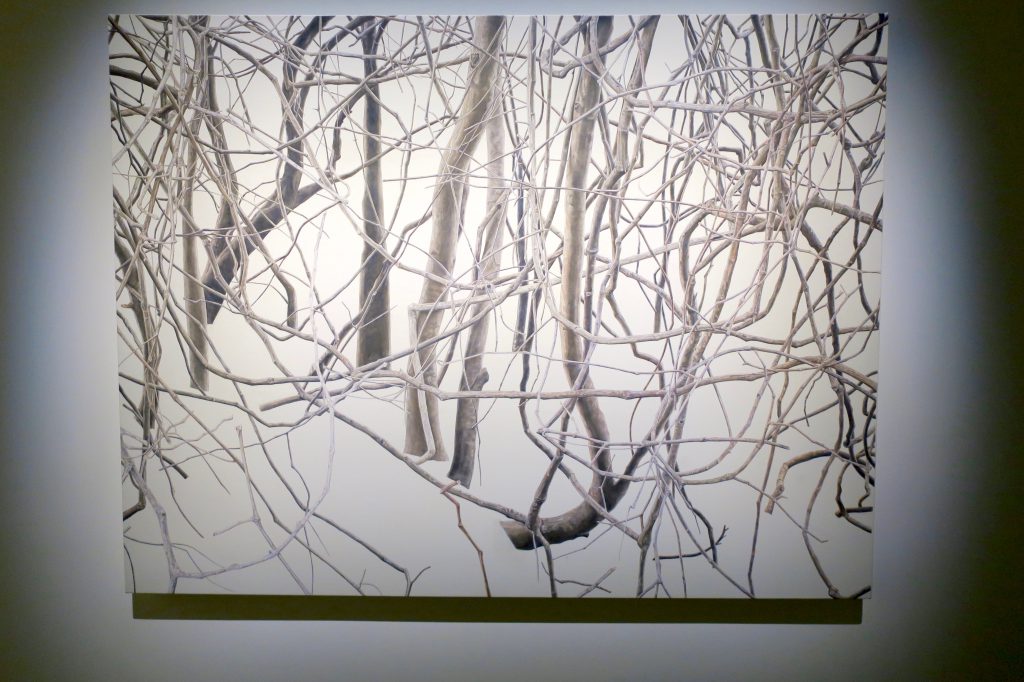

Toba Khedoori: Untitled (branches 1) 2011-12

oil on linen

Peter Doig: The Architect’s Home in the Ravine 1991

oil on canvas

Eva Jospin: Forêt Palatine (detail) 2019-20

wood and cardboard

Tacita Dean: Crowhurst II 2007

gouache on photograph

The yew in this photograph is one of the oldest living trees in the UK. Like many ancient yews, it stands in a churchyard. Associated in Christian thought with resurrection and eternal life, yews were also considered sacred by druids, and some predate not only their neighbouring churches, but also Christianity. As Dean’s photograph shows, some of the branches of this tree have been propped up with crutch-like supports – potentially misguidedly, as when a yew’s drooping branches reach the ground, they are able to take root. ‘Crowhurst II’ is one of a series ‘painted trees’ that the artist began in 2005. Setting out to research the UK’s oldest living trees, Dean discovered that one (Majesty) grew close to her childhood home, while another – the yew pictured here – shared its name with Donald Crowhurst, an ill-fated amateur sailor lost at sea in 1968 – and the subject of a number of Dean’s earlier works.

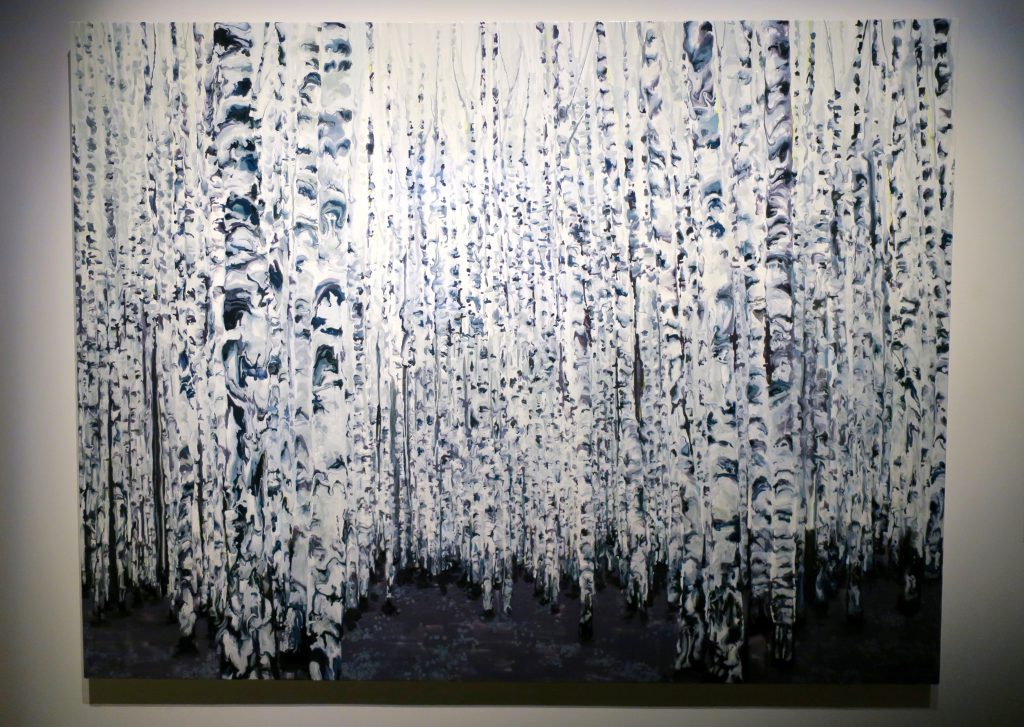

Kirsten Everberg: White Birch Grove, South (After Tarkovsky) 2008

oil and enamel on canvas on panel

Giuseppe Penone: Tree of 12 Metres 1980-82

wood

For Giuseppe Penone, trees are ‘perfect sculptures’. ‘What fascinates me about trees is their structure’, he comments. ‘The tree is a being that memorialises the feats of its own existence in its very form’. For ‘Tree of 12 Metres’, Penone took a large piece of industrially planed timber and – following one of its growth rings and paying attention to its knots – scraped away at the wood to reveal the organic form of the once-living tree inside. For Penone, every wooden ‘door, table, window, or board’ contains ‘the image of a tree’. Over the past 50 years, he has made a number of similar sculptures at different scales. To him, the process offers ‘a new adventure every time’. Penone’s ‘Tree of 12 Metres’, an American larch, is shown here in two parts – its top section upside down.

Rodney Graham: Gary Oak, Galiano Island 2012

transmounted c-print

Robert Smithson: Upside Down Tree 1, 1969

Alfred, New York, USA

exhibition print from 35mm slide

Robert Smithson: Upside Down Tree 2, 1969

Captiva Island, Florida, USA

exhibition print from 35mm slide

Robert Smithson: Upside Down Tree 3, 1969

Yaxchilan, Yucatán, Mexico

exhibition print from 35mm slide

Eija-Liisa Ahtila: Horizontal – Vaakasuora 2011

6-channel projected installation

Eija-Liisa Ahtila describes this massive multi-part video-work as a ‘portrait of a tree’. The spruce is common to the artist’s native Finland. With this work, Ahtila attempts to show the tree in its entirety, as far as possible retaining its natural size and shape. Because a tree of this scale does not fit easily into a human space, it is presented horizontally in the form of successive projected images. Each of the six sections plays slightly out of sync. The work is a record of a living organism. It also deals with the limits of recording technologies that we use to create images of the world around us. In particular, it addresses the difficulty of perceiving and recording other living beings through methods invented by humans, which record and reproduce our human perspective of the world. Photo @vanesther1.

Gallery 1 and Gallery 2 are dimly lit subarboreal spaces with pictures illuminated in pools of light, an enchanted forest with the rustling of branches and occasional birdsong on the installation soundtrack. After a magical woodland walk we emerge blinking into the bright lights of Gallery 3…

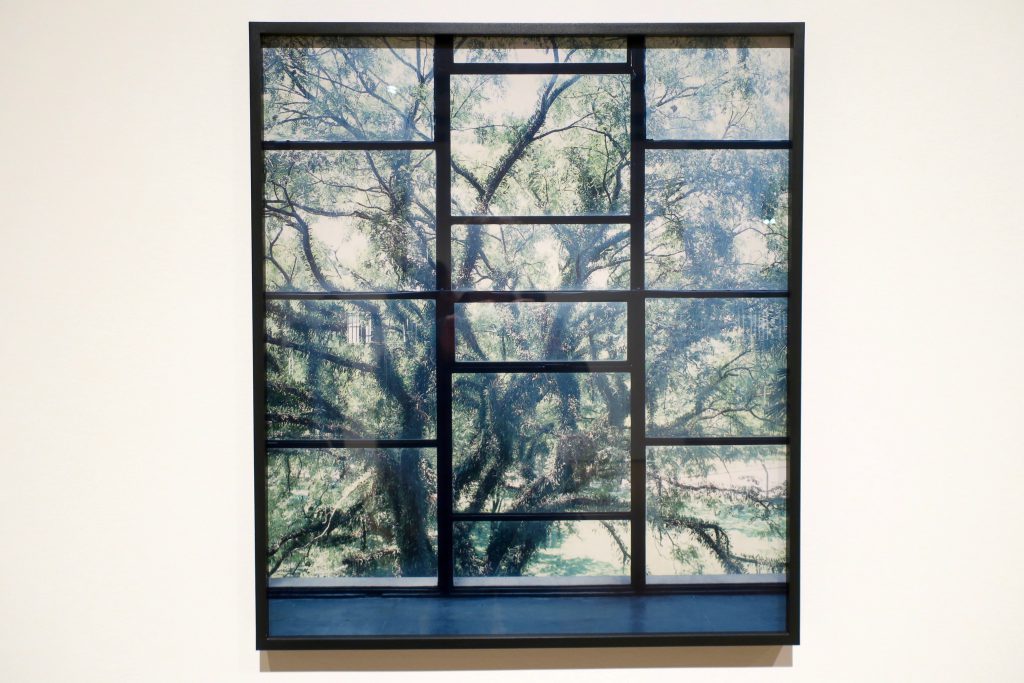

Luisa Lambri: Untitled (Palácio da Indústria #01) 2003

lambda print mounted on acrylic

It is impossible to separate the life of trees from the impact of human activity. A recent study estimates that the number of trees on earth has declined by almost 50% since people started farming 12,000 years ago.

Many of the artworks in this section of the exhibition address the ways in which arboreal life has been affected by industry, agriculture and human conflict, as well as the growth of towns and cities. Instead of depicting trees as belonging to a separate world of ‘nature’, these works underscore how entwined their existence is with our own. We are presented with woods as places of work; as sites of revelry and excess; and as places marked, and in some cases haunted, by historical events. These artists remind us that while trees and forests are indispensable to our lives and our imaginations, our relationship to them is far from simple.

Some of these artists also reflect on the different cultural filters – the common traditions and visual conventions – that colour our perception and understanding of trees and forests. In the process, they open up new possibilities for thinking about how we relate to them, and the varied roles – economic, practical, emotional – they play in our everyday lives.

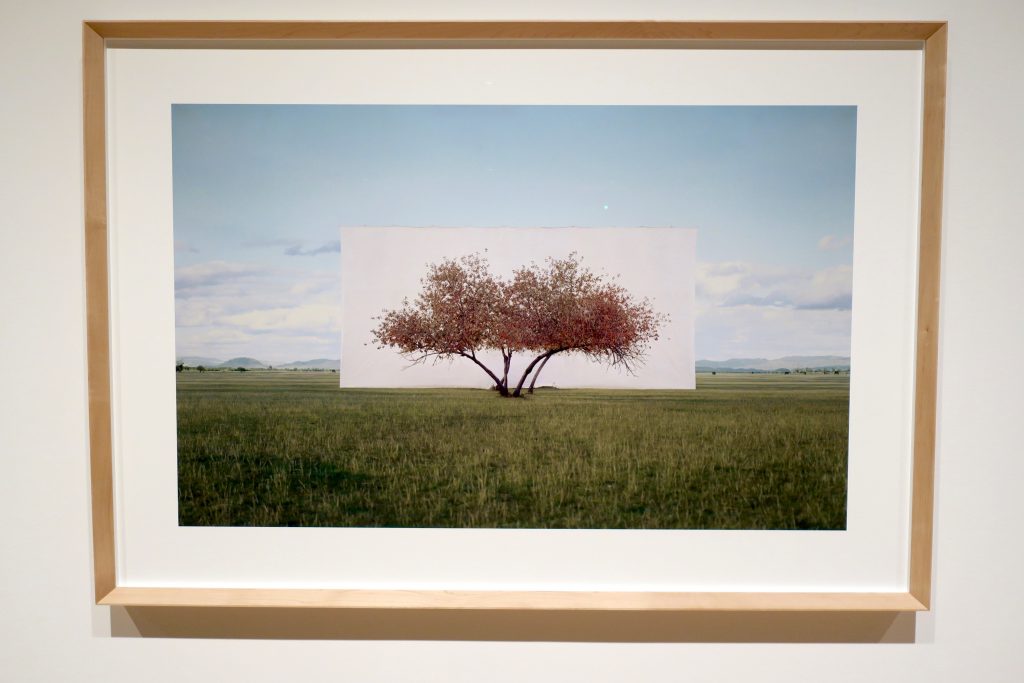

Myoung Ho Lee: Tree… #2 2012

ink on paper

Sally Mann: Deep South, Untitled (Scarred Tree) 1998

gelatin silver print – tea-toned

Sally Mann: Deep South, Untitled (Fontainebleau) 1998

gelatin silver print – tea-toned

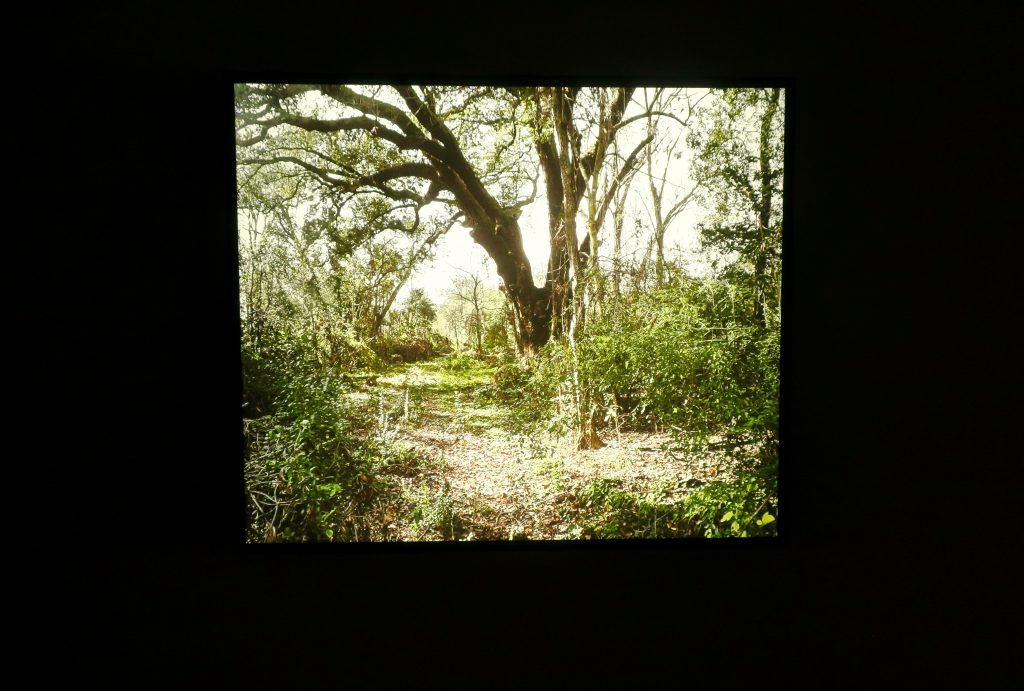

Steve McQueen: Lynching Tree 2013

light box with transparency

Roxy Paine: Rotoplasm 2012

stainless steel and enamel

Abel Rodriguez: Terraza Baja, 2018

acrylic on paper

Abel Rodriguez: Terraza Alta II, 2018

acrylic and ink on paper

Abel Rodriguez, an elder from the Nonuya ethnic group, native to the Cahuinari river in the Colombian Amazon, learnt everything he knows about trees and plants from his uncle. He first started drawing in his 60s, having had no prior training. In the 1990s, Rodriguez and his family were displaced from their home as a result of armed conflict. His detailed drawings – which often depict the rainforest’s intricate ecosystem as it appears at different times of the year – are made from memory.

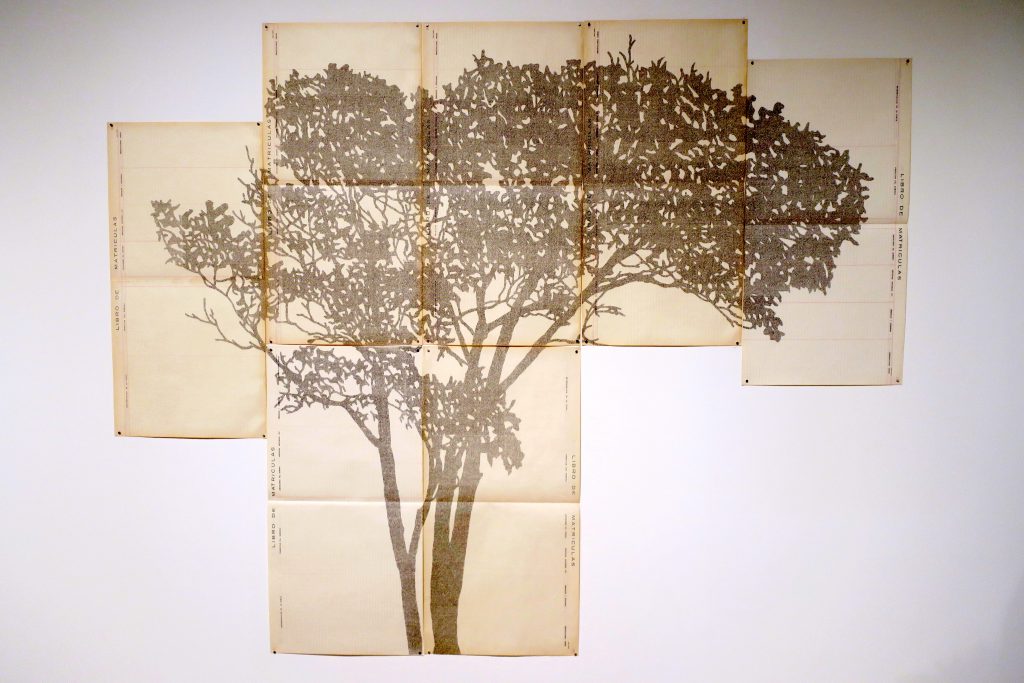

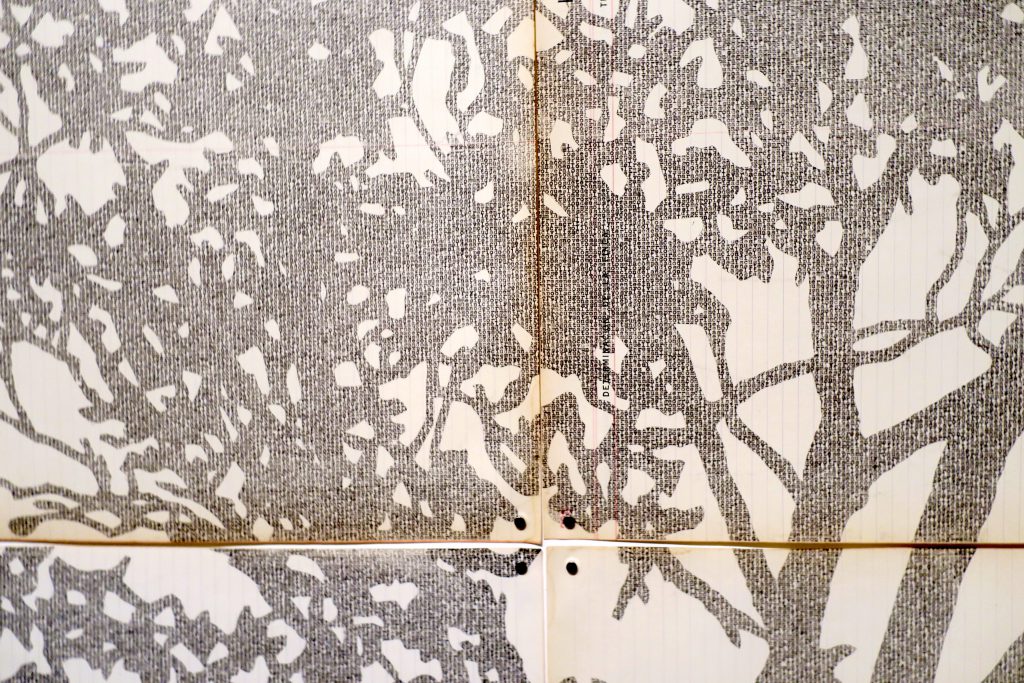

Johanna Calle: Perimetros (Nogal Andino) 2012

typed text on vintage notarial ledgers

Johanna Calle tackles emotive subjects using materials and processes that are, in her words, deliberately ‘austere’. In this work, the silhouette of an Andean walnut tree has been formed from dense typewritten text taken from Colombia’s 2011 Law of Land Restitution, a law that recognises the rights of people displaced by armed conflict. Calle has typed the text onto blank pages taken from an antique notary book that once recorded changes in land ownership. Like much of Calle’s work, this drawing questions the power and authority of the written word over oral traditions. The silhouette of the Andean walnut refers to the historic practice of planting trees to delineate land ownership.

There was something intriguingly familiar about this one. Then I remembered @fondationcartier.

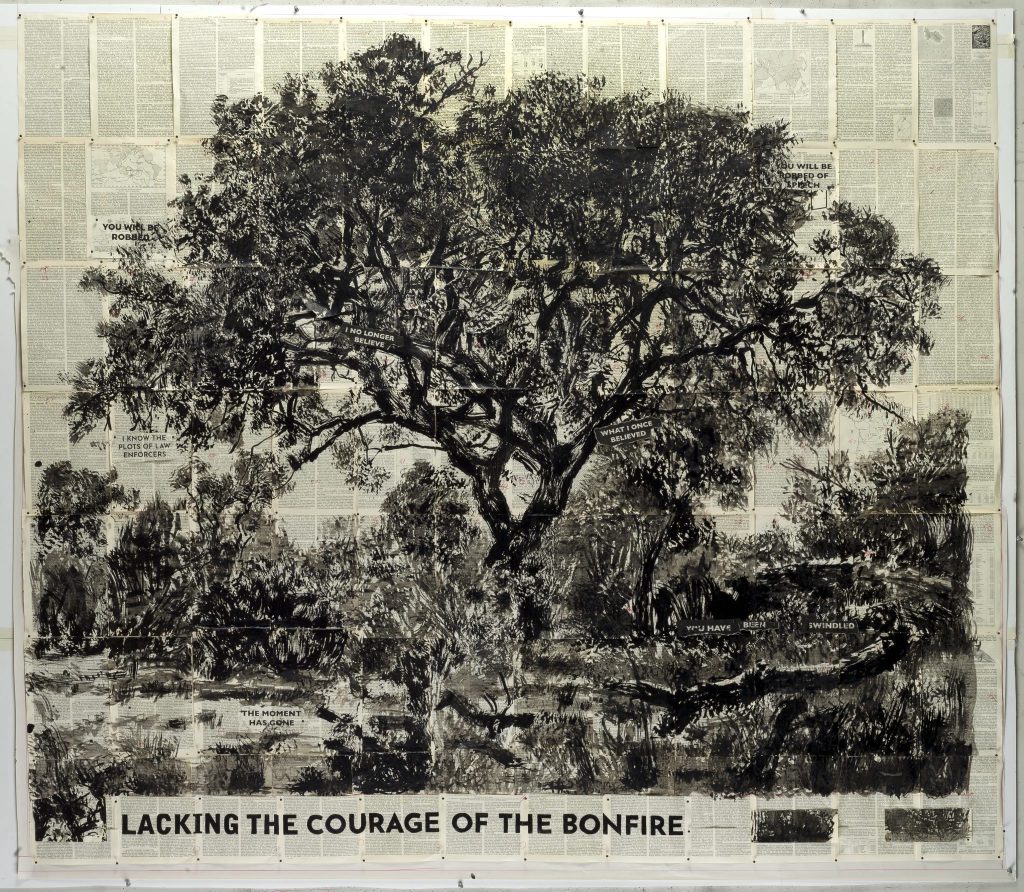

William Kentridge: Untitled (Lacking the Courage of the Bonfire) 2019

Indian ink on found papers

Anya Gallaccio: because I could not stop 2002

direct-cast bronze, ceramic, rope

This bronze apple tree was cast from a living but condemned tree. Apple trees are of interest to Anya Gallaccio partly because of the way they function as sculptural objects. Dependent on human intervention to perform at their best, they are – as Gallaccio sees it – already ‘designed’, ‘constructed’ and ‘sculpted’ by the labour of the gardener. Strung across the boughs of this bronze tree are swags of ceramic apples, a fruit laden with conflicting cultural associations – from health and wellbeing to original sin. The scorched floor it sits on adds to a sense of ill-defined unease – a reminder, perhaps, of the vulnerability, or combustibility, of wood.

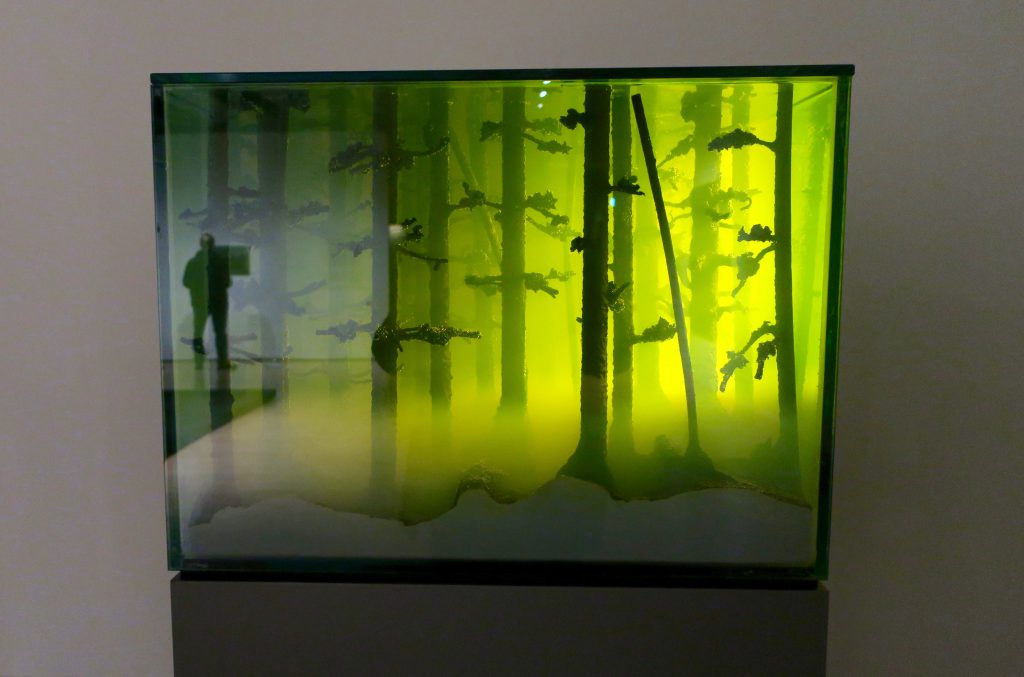

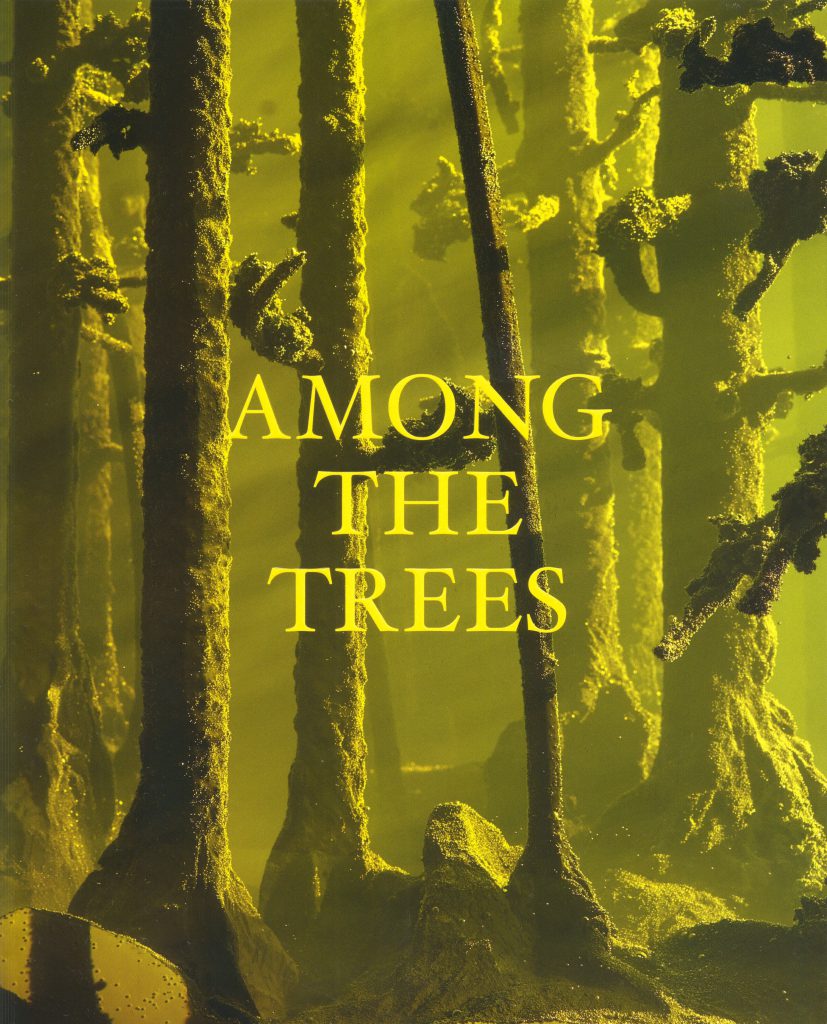

Mariele Neudecker: And Then the World Changed Colour: Breathing Yellow 2019

mixed media including water, acrylic, salt, fibreglass, spotlight

With her submerged landscapes, Mariele Neudecker hopes to create a space where ‘the real and the imaginary collide’. Her tank sculptures raise questions about how we perceive and respond to images of the world around us, particularly the ‘natural’ world. In these works, the sublime landscapes depicted by Romantic painters appear simultaneously vast and uneasily contained. Although this forest is empty of people, the artist intends their presence to be felt. We are looking at ‘a cultural, human space, not an untouched bit of nature’. The yellow light that suffuses the scene adds to its sense of otherworldliness, and reinforces the idea that this is a landscape contaminated by human activity.

It also features on the cover of the exhibition catalogue.

From Gallery 3 we ascend the Hayward’s brutalist concrete staircase, climbing alongside Giuseppe Penone’s Tree of 12 Metres, overlooking Gallery 1 where we started from. It’s suddenly reassuring to notice the detail of the shutter-formed walls and their echoes of ancient half-timbered constructions.

Pascale Marthine Tayou: Plastic Tree B 2020

wild tree, plastic bags, plants and pots

Errant plastic bags caught in trees in Ireland are colloquially known as Witches’ Knickers.

Jennifer Steinkamp: Blind Eye, 1 2018

video installation

As we watch this computer animation of birch trees swaying in the breeze, their leaves changing colour with the seasons, falling to the ground then being reborn, I begin to feel queasy. I imagine it projected onto the wall of a hotel lobby when the trees are all gone and we need to be reminded what they looked like. I’m being processed, undergoing a “visitor experience”, and I wish I was in the forest. I can’t help thinking of Joni Mitchell…

They took all the trees

And put them in a tree museum

And they charged all the people

A dollar and a half just to see ’em

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot.

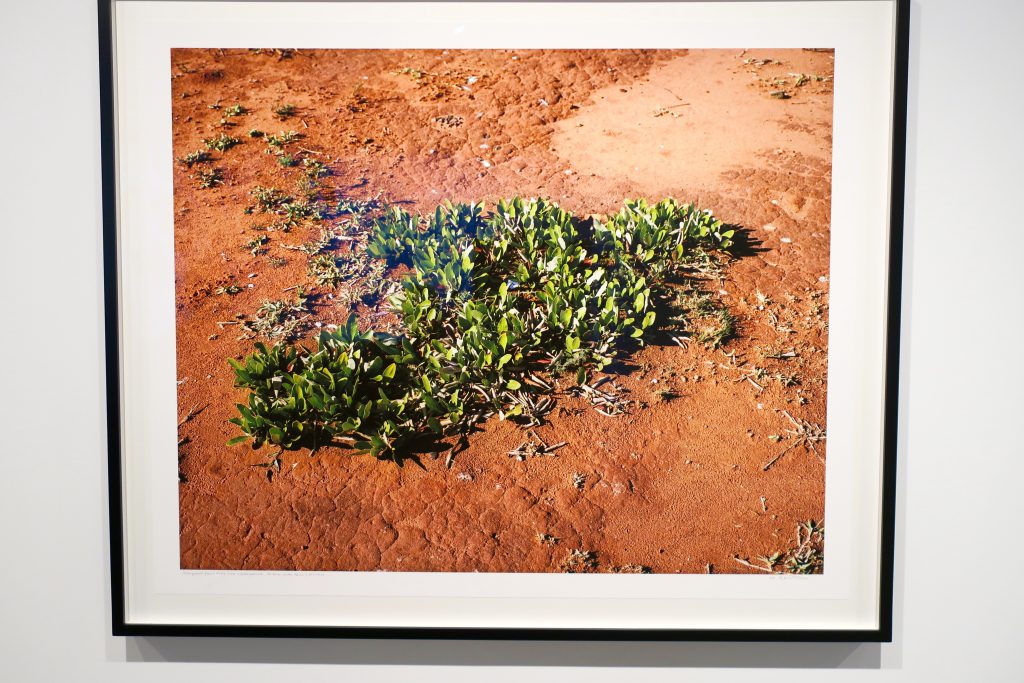

Rachel Sussman: Underground Forest #0707-1333

(13,000 years old; Pretoria, South Africa) DECEASED 2007

archival print

The greenery in this photograph is not a shrub, but rather the uppermost crown of an underground tree growing in Pretoria, South Africa. Botanists speculate that these remarkable trees – known collectively as underground forests – have migrated underground in order to avoid being damaged by the area’s regular wildfires. This 13,000-year-old clonal tree, like many of the organisms that Sussman photographed, has since been destroyed as a result of human activity, in this case the construction of a new road.

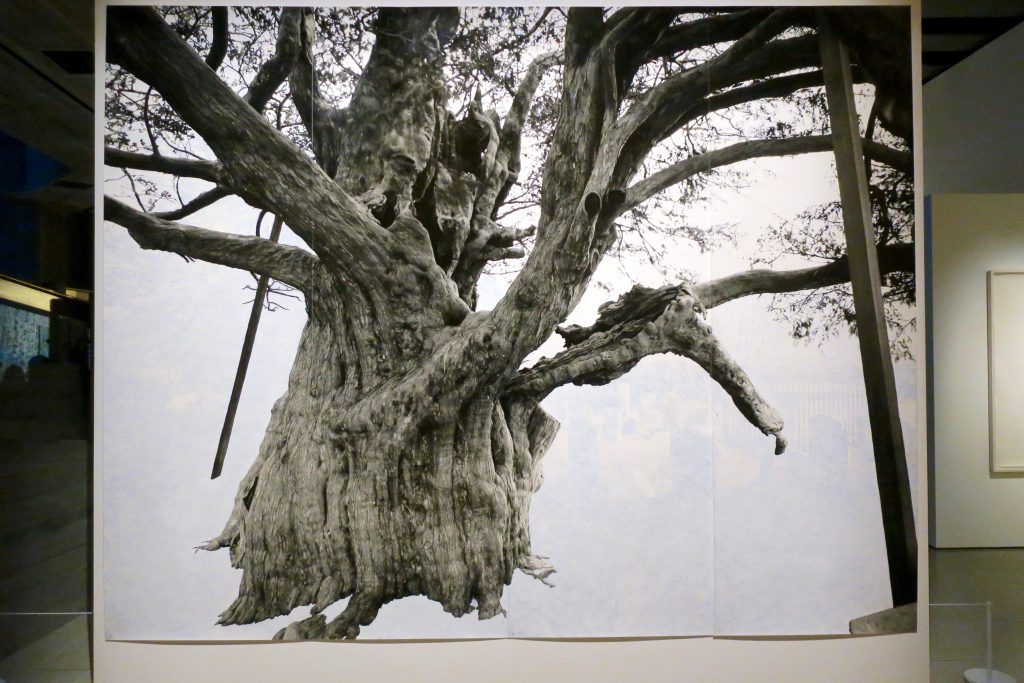

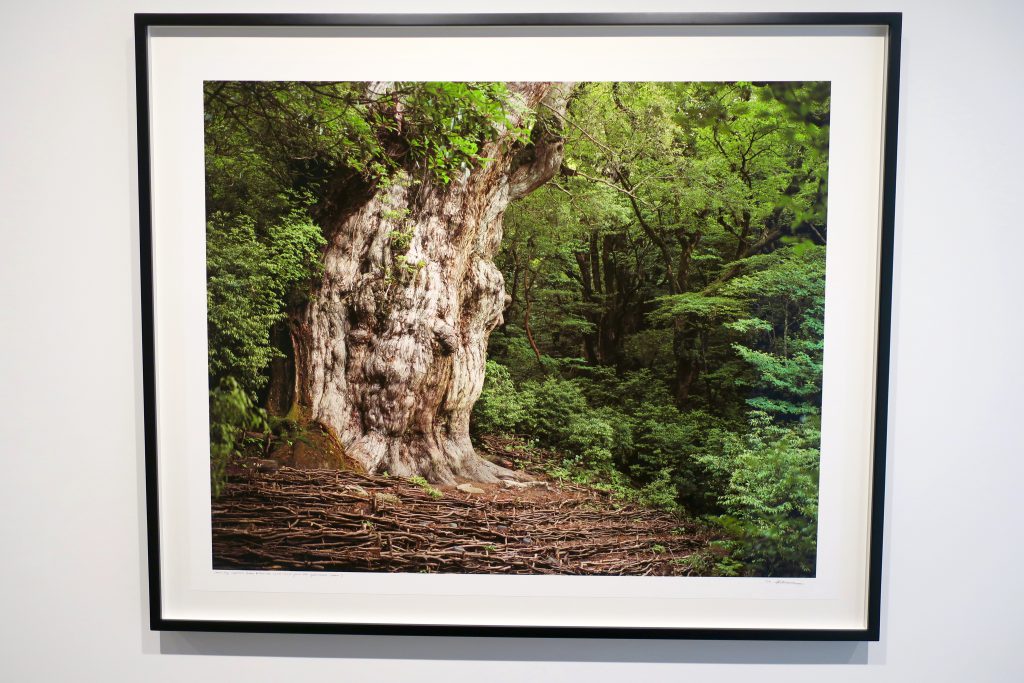

Rachel Sussman: Jamon Sugi, Japanese Cedar #0704-002

(2,180-7,000 years old; Yakushima, Japan) 2004

archival print

In ‘The Tree’, novelist (and amateur naturalist) John Fowles remarks that trees create a variety of times: their existence reflects seasonal changes as well as annual cycles of growth, while their life spans – which can reach thousands of years – often far exceed our own. A tree’s rings, meanwhile, comprise a kind of organic recording device that contains information about past climate conditions – including temperature and rainfall – as well as data on events that in some cases date back to earlier eras of human history. As the artist Giuseppe Penone remarks, ‘The tree is a being that memorialises the feats of its own existence in its very form’.

A number of artists in this section of the exhibition explore the layered relationship between trees and time. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of these works read as memorials, or memento mori. They confront us with the increasing precarity of arboreal life due to unsustainable human activity, as well as with the relative briefness of our own lives compared to these long-lived organisms. These multifaceted artworks also invite us to recalibrate our mental clocks, and to consider the ways in which different living organisms can be seen to inhabit distinct, but co-existing time zones.

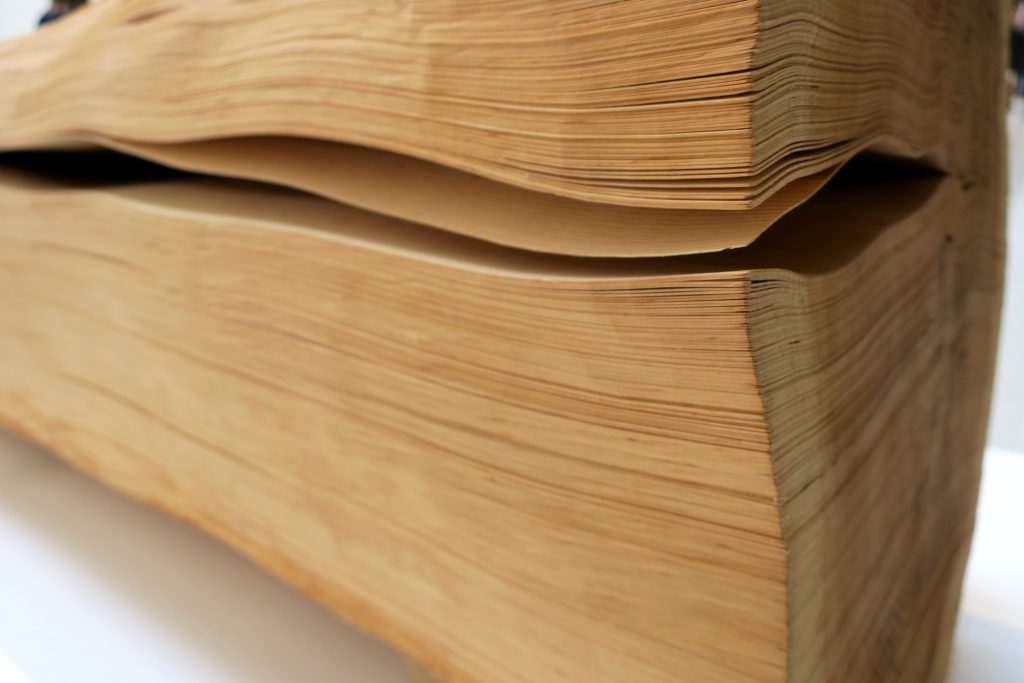

Kazuo Kadonaga: Wood No.5 CH 1984

cedar

Kazuo Kadonaga comes from a long line of people who work with trees. His family owned cedar forests and ran a lumber mill in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. For the past 50 years, Kadonaga has made three-dimensional works that treat both the material and his processes as subjects by exploring the physical properties of materials such as wood, bamboo, paper, glass and silkworms. To make ‘Wood No.5 CH’, the artist stripped the bark from the trunk of a cedar tree and sliced it into around 800 paper thin sheets, using a machine commonly used to make decorative veneers. Once dried, these sheets were carefully reassembled, and the trunk restored to its original form.

Ugo Rondinone: cold moon 2011

cast aluminium, white enamel

Ugo Rondinone’s ‘cold moon’ was cast from an ancient olive tree growing in southern Italy. The tree’s peculiar shape is the result of centuries-long exposure to the elements. It is one of a series of 12 sculptures, each named after a full moon and cast from trees aged between 1,500 and 2,000 years old. For Rondinone, this ungainly, ghostly tree acts as a ‘memorial of condensed time’. ‘Time becomes a lived abstraction’, he comments, ‘where the shape of the ancient olive tree is formed by an accumulation of time, and the force of earth, air, water and fire’.

Next up, and probably the highlight of the exhibition for me, was this corner of Gallery 5 devoted to three more works by Giuseppe Penone. I’m reminded of Andrei Tarkovsky’s book, Sculpting In Time.

Giuseppe Penone: Soffio di foglie 1982

wood, bronze

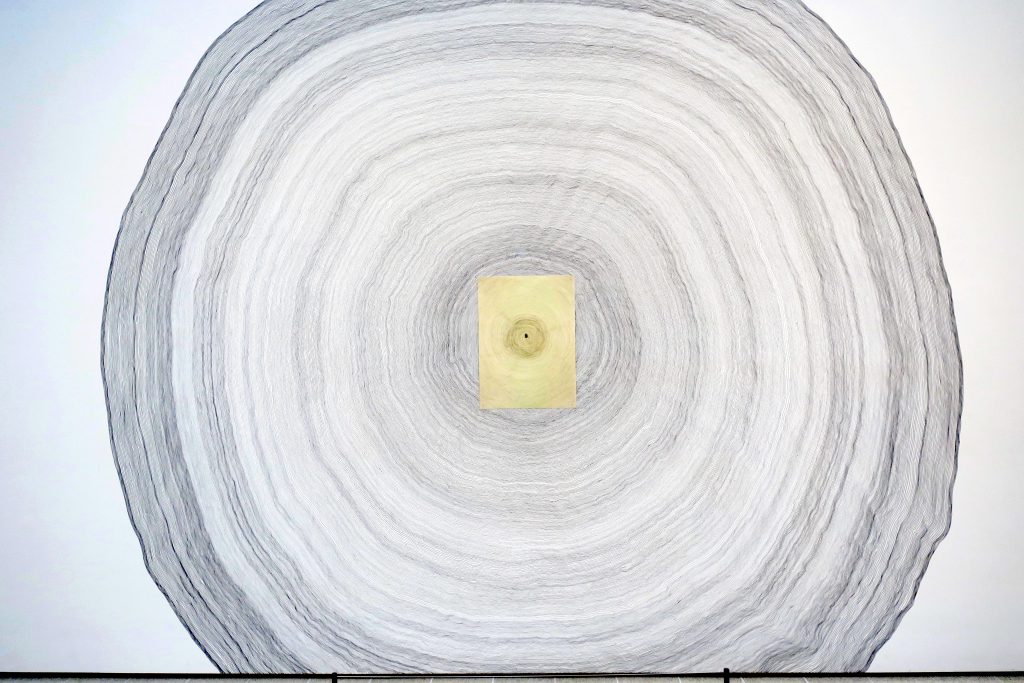

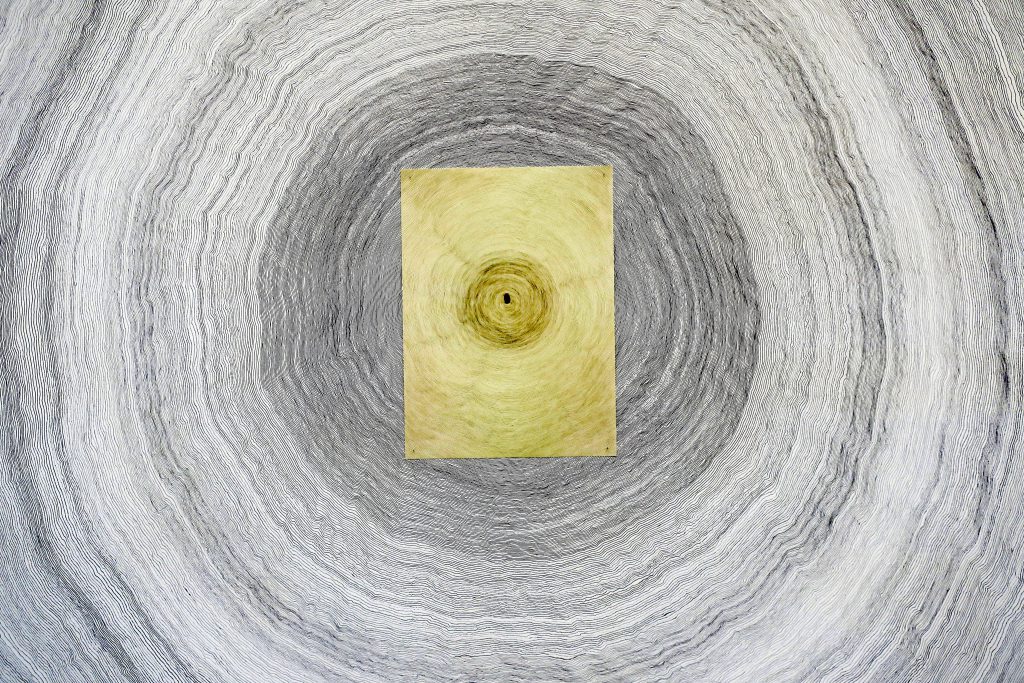

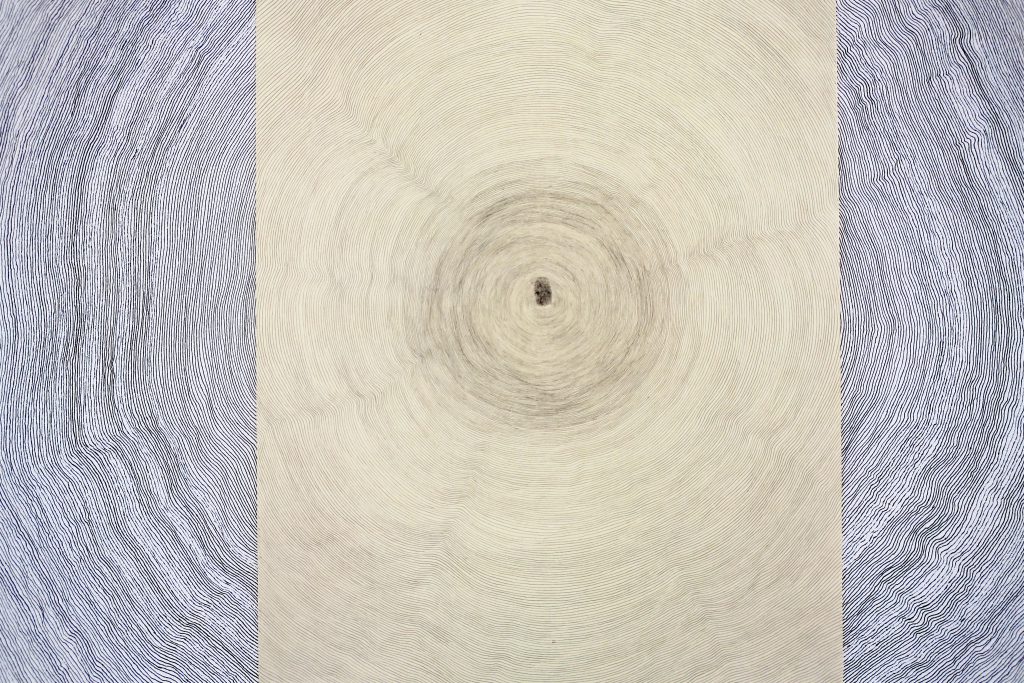

Giuseppe Penone: Propagazione 1995-2019

wall drawing

Giuseppe Penone: Albero Porta 2012

cedar

Giuseppe Penone carved ‘Albero Porta’ from a large, untreated trunk, using the same process that he used for ‘Tree of 12 Metres’, on display downstairs. This sculpture – made more than 40 years after the artist started working with trees – is concerned with time, and the process of ageing. Visible at the base of the cavity are the rings that chart the tree’s growth. The same concentric circles or ‘growth rings’ make up Penone’s large-scale wall drawing ‘Propagazione’, at the centre of which is the artist’s thumbprint. Although his primary material is wood, Penone also makes sculptures using bronze, a material he considers almost ‘vegetal’. The bronze element of ‘Soffio di foglie’ (in English, ‘breath of leaves’) is a cast of the shape of the artist’s body made in a pile of leaves.

This seems to me to be the ideal sculpture. To carve into the wood to find the idea waiting to be discovered. He peels away the growth rings to expose a younger version of the tree hidden inside. It appears to be the tree’s skeleton and also its memory. A doorway into the past revealing the once new life within. A secret place, a woodland chapel, the immanent heart of the forest.

※

Among The Trees is a fantastic exhibition, very welcome and long overdue. There’s much to admire and I particularly love these pieces by Giuseppe Penone, but he’s a hard act to follow. This was the penultimate exhibit. The sad finale was where the exhibition fizzled out, in a space devoted to an unconvincing tableau of wildfire embers that looked more like a giant domestic log-effect electric fire.

※

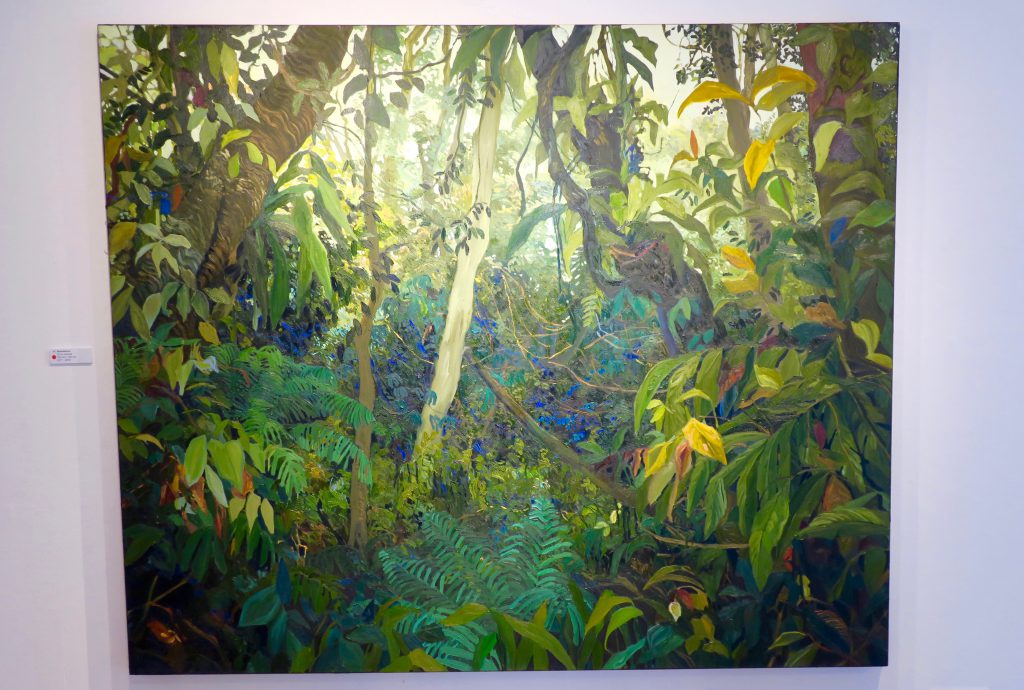

But here, on Frames of Reference, I can substitute my own alternative ending. And I can’t help but imagine that final room occupied by four of Jelly Green‘s magnificent and monumental rainforest paintings. And with a soundtrack of Jonathan Pryce reading from W G Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (just as he did in Grant Gee’s film Patience (After Sebald)).

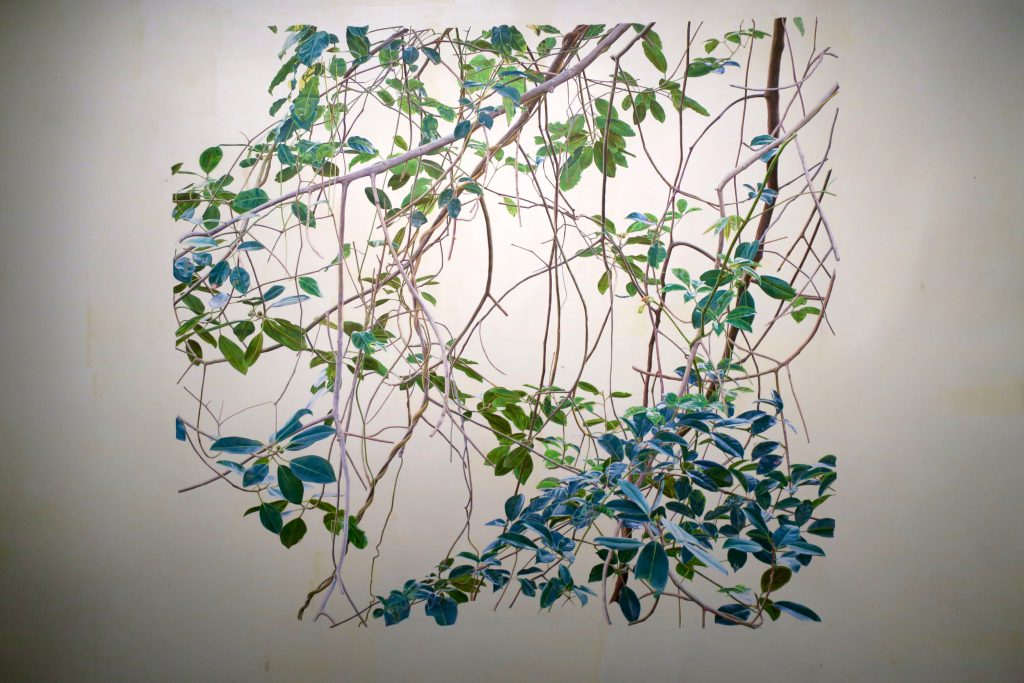

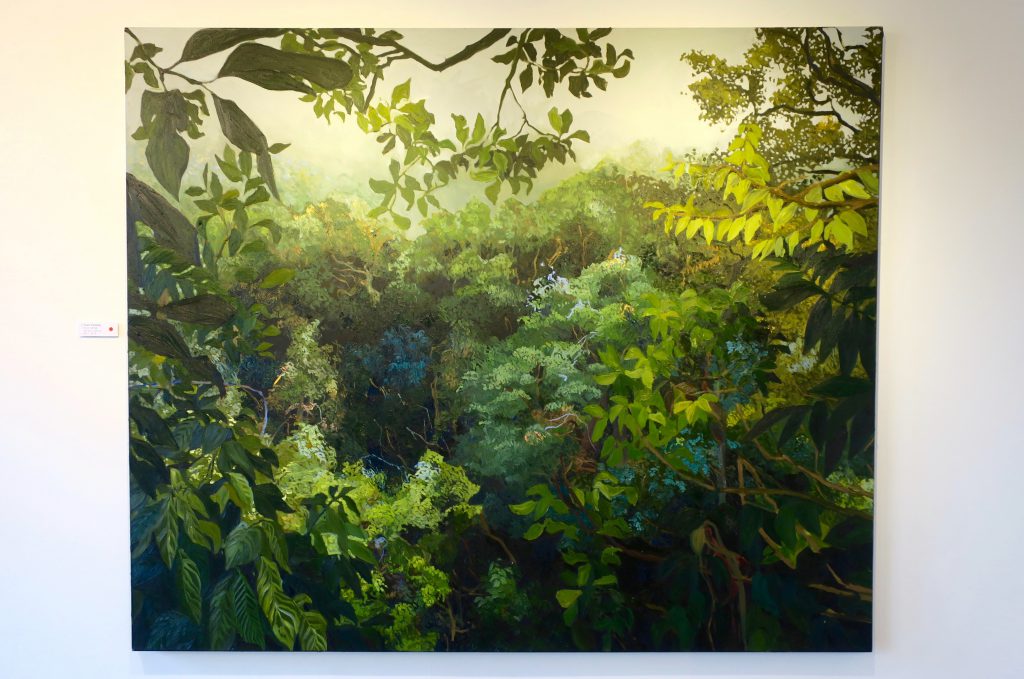

Jelly Green: Abundance 2017-18

oil on canvas

It had grown uncommonly sultry and dark when at midday, after resting on the beach, I climbed to Dunwich Heath, which lies forlorn above the sea. The history of how that melancholy region came to be is closely connected not only with the nature of the soil and the influence of a maritime climate but also, far more decisively, with the steady and advancing destruction, over a period of many centuries and indeed millennia, of the dense forests that extended over the entire British Isles after the last Ice Age. In Norfolk and Suffolk, it was chiefly oaks and elms that grew on the flatlands, spreading in unbroken waves across the gently undulating country right down to the coast. This phase of evolution was halted when the first settlers burnt off the forests along those drier stretches of the eastern coast where the light soil could be tilled. Just as the woods had once colonised the earth in irregular patterns, gradually growing together, so ever more extensive fields of ash and cinders now ate their way into that green-leafed world in a similarly haphazard fashion.

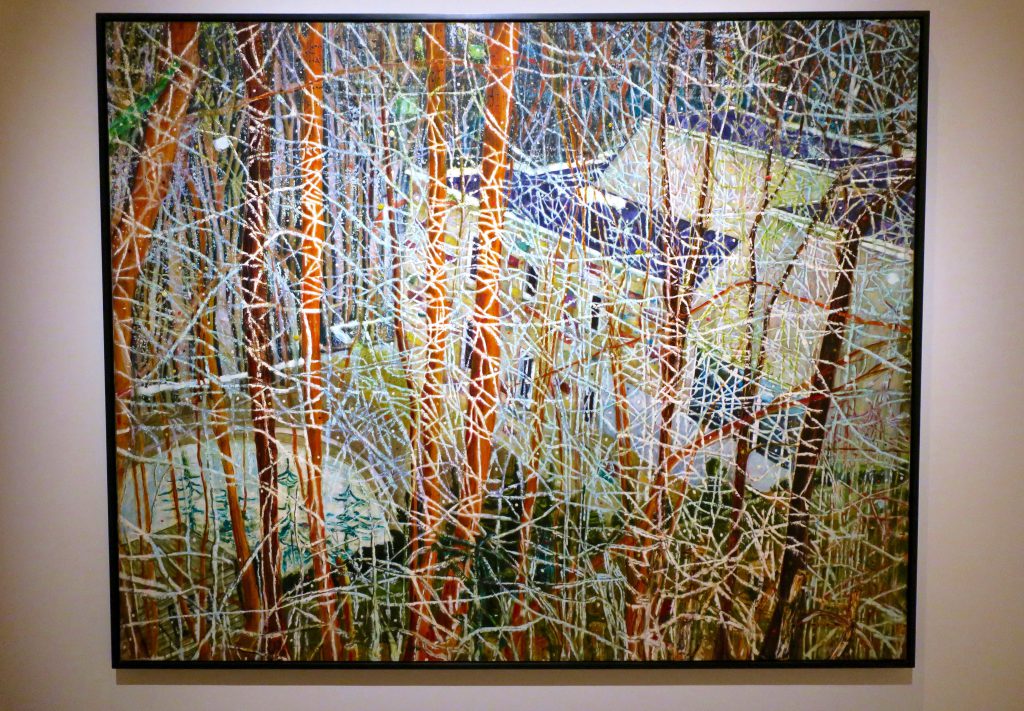

Jelly Green: Fool’s Paradise 2017-18

oil on canvas

If today one flies over the Amazon basin or over Borneo and sees the mountainous palls of smoke hanging, seemingly motionless, over the forest canopy, which from above resembles a mere patch of moss, then perhaps one can imagine what those fires, which sometimes burned on for months, would leave in their wake. Whatever was spared by the flames in prehistoric Europe was later felled for construction and shipbuilding, and to make the charcoal which the smelting of iron required in vast quantities. By the seventeenth century, only a few insignificant remnants of the erstwhile forests survived in the islands, most of them untended and decaying. The great fires were now lit on the other side of the ocean. It is not for nothing that Brazil owes its name to the French word for charcoal.

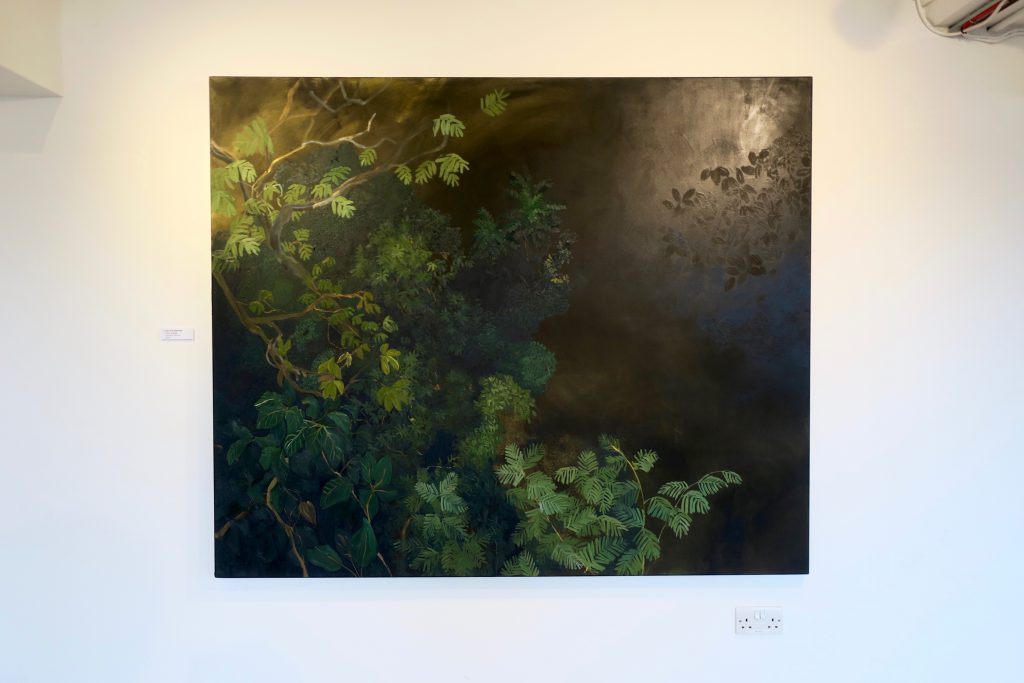

Jelly Green: Into The Shadows 2018

oil on canvas

Our spread over the earth was fuelled by reducing the higher species of vegetation to charcoal, by incessantly burning whatever would burn. From the first smouldering taper to the elegant lanterns whose light reverberated around eighteenth-century courtyards and from the mild radiance of these lanterns to the unearthly glow of the sodium lamps that line the Belgian motorways, it has all been combustion. Combustion is the hidden principle behind every artefact we create. The making of a fish-hook, manufacture of a china cup, or production of a television programme, all depend on the same process of combustion. Like our bodies and like our desires, the machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers…

Jelly Green: Decimate 2017-18

oil on canvas

※

Awesome and beautiful, thanks for posting so that I could experience this exhibit.

Thank you for this wonderful post Chris. I cancelled my planned London trip next week – Ceramic Art London cancelled and travelling started to look a bit stupid! So I’m missing this exhibition, amongst others – so it’s brilliant to get all your detail and I’m sure I’d prefer your end to the exhibition to the actual exhibit. I loved your moving Hepworth post too – sad times for you but art always helps. Hope you and Sue are well – I will be down once this chaos is all over!

Julia

Yes, now is probably not the best time to be coming down from Scotland. They say we’re at the epicentre of covid 19 in Kensington & Chelsea, so not sure how much longer we’ll be able to stay open. Stay home and stay safe!

Wonderful to view from Florida, USA.

Better late than never.

Fabulous exhibit. Thanks.