We came to Symondsbury for breakfast, the best coffee and bacon roll in months, then down past the church and up the hill to Shute’s Lane. We were staying under Eggardon and we’d already driven down a tunnel of green lanes to get here. This one was closed to traffic so now we were on foot.

Pretty soon we were swallowed up by a clean-cut dream of dappled shade, banks of ferns and overarching trees and a delicious bath of green light.

I looked up at the top of the bank just as a figure ran past, calling out as she went, and I imagined Alice’s sister above as we descended into Wonderland.

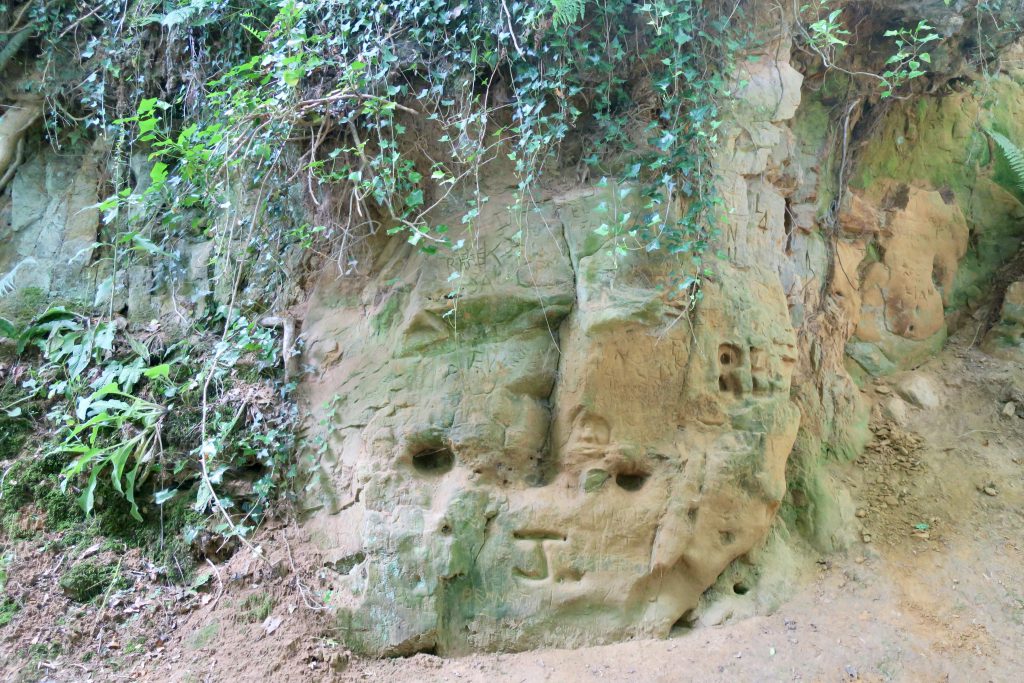

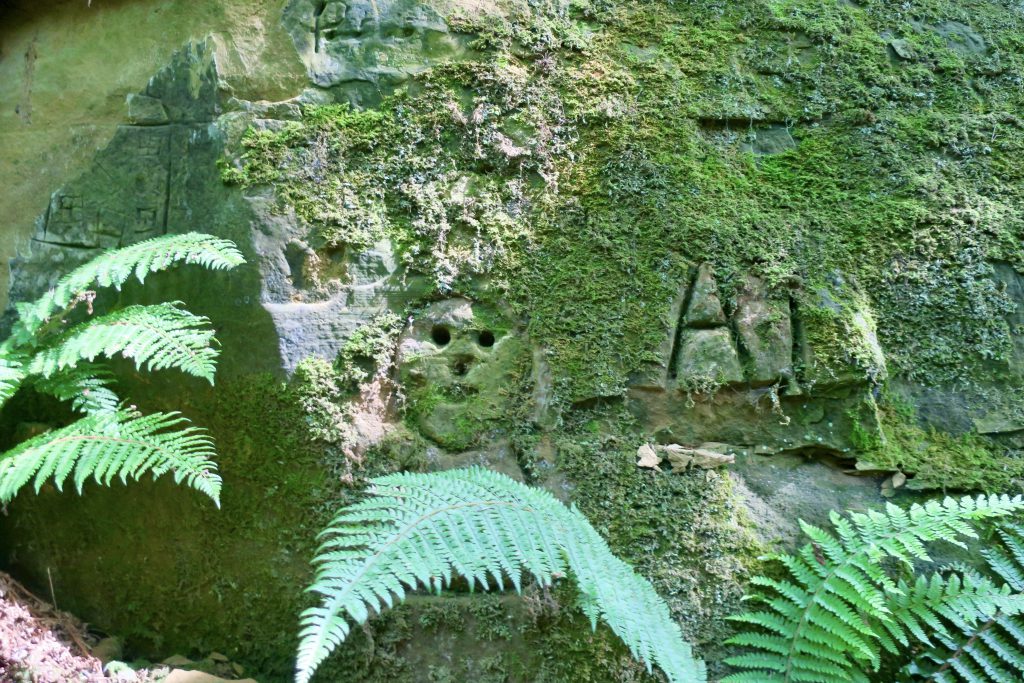

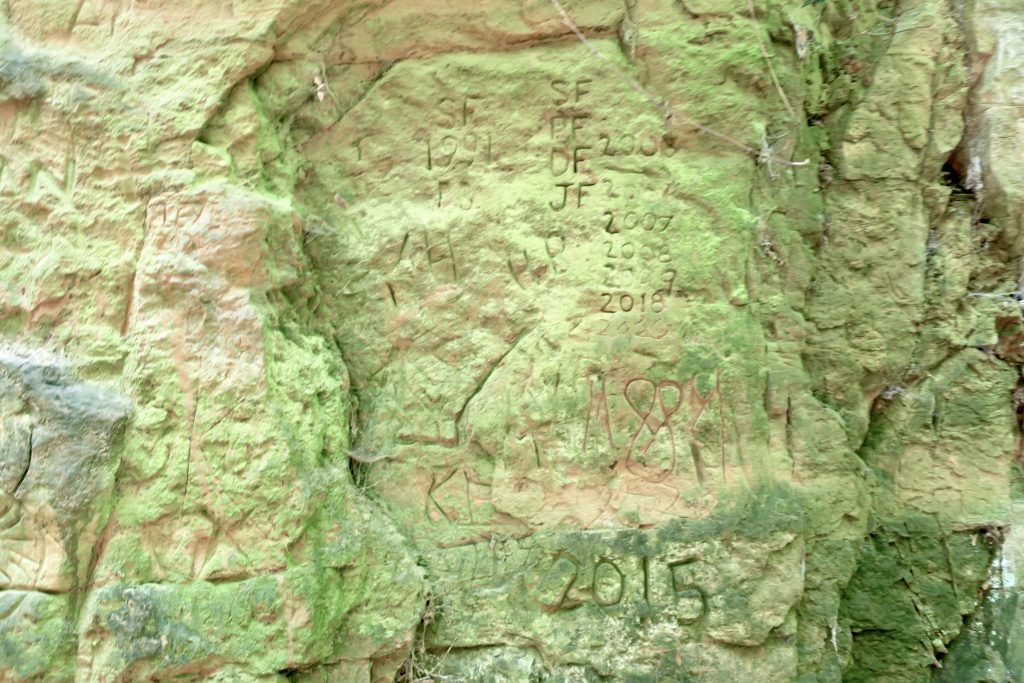

Here and there the exposed sandstone rocks have been inscribed with brief cryptic messages, glyphs and tags and recipes from the underworld.

After maybe half a mile or so of narrow single carriageway it was a surprise to come upon a little house with a little car parked outside. Perhaps it’s the home of the holloway gatekeeper? Where the holloway caretaker lives?

The path forks and descends deeper into a steep-sided sunken lane between sandstone cliffs, so though we’re still climbing we’re further underground.

We’re illuminated by dancing spotlights shining through the leaves.

We’re watched by holloway guardians carved into the rock walls.

This whole holloway is itself a carving, carved by water and feet and hooves and cartwheels, carved by the passage of time and weather, of light and life.

There are carvings that dance quickly on the wall.

And carvings that don’t move at all.

Light moves and carves the walls with shadows.

Dazzled and delighted we emerge at last at Quarry Cross, a brief moment under the hills and sky, before we go down the rabbit hole into Hell Lane.

It’s gloomy and damp, with none of the fine carvings of Shute’s Lane, just random graffiti and a steep path, rutted and ankle-twisting, but it’s green and enveloping and there’s nowhere I’d rather be. Back down to earth…

Occasionally surfacing…

Coming up for air to get our bearings and to meet the neighbours, before diving back down again into the green.

The rejuvenating green.

Our path became a stream and we were grateful for waterproof shoes.

At North Chideock we visited the Church of Our Lady, Queen of Martyrs & St Ignatius and its museum of Chideock through the ages – Cidhoc, Cydyok, Chydiocke, Chydyok, Chideok, Chidiocke, Chidyoke, Chidwick.

“Where the road ran to its end, we found an emblem for our adventure. Just to the east of the road, set back amid oak trees and laurel bushes, was a small Catholic chapel, built of pale sandstone in a Romanesque style. We pushed open a wooden gate, and walked down a leaf-strewn path to the chapel’s porch. Its door was huge, of ridged oak, studded with black square-headed bolts. It opened with an ease that belied its weight, its bottom edge gliding above the flagstones of the porch, which were dipped by the passage of many feet.

The air inside the church was cool, and the sandstone of its walls and pillars was chilly to the touch. There was a faint odour of must, and everywhere the glint of gilt: saints in their niches, a golden altar rail, a gleaming candlestick at either end of the mensa. Striking through the air at angles were needles and poles of sunlight, sieved by the windows, in which dust motes rose and fell slowly, like gold leaf in warm water.

The Chideock Valley has a recusant past. After the Act of Supremacy in 1558, when Catholic priests were banned from Britain, missionaries began to re-infiltrate England in order to keep the faith alive. Chideock had long been a Catholic enclave, and several priests came to the area to offer clandestine ministry. A high-stakes game of hide-and-seek began. The priests went fugitive in the landscape, taking asylum in the woods, caves, copses and holloways of the area. Soldiers combed the countryside for them and their supplicants. Mass was held in secret in a hayloft in one of the Chideock farmhouses. Over the course of fifty years of this recusancy, at least three laymen and two priests were caught, tortured and executed. The chapel had been built in the nineteenth century as a memorial to these ‘Chideock Martyrs’.

Robert Macfarlane: The Wild Places

We bought a map (2.5 inches to the mile) from the village stores and drove up to North Chideock, where we left the car in the leafy, shaded car park of the Catholic Chapel of Chideock Manor. It is a hidden, well-wooded, secluded place, reached by walking along a tall box hedge and passing the spreading arms of laurels, limes, planes and oaks. All its traditions relating to the Chideock Martyrs, the Catholic priests, are about hiding, outlaws, covert activities. The Chideock Martyrs actually hid from the authorities and lived in the woods for some weeks – sixteen, I think.

We packed our rucksacks with water and food, and camping gear, and set off up the hill through the village towards Venn Lane, which we entered about midday. Past Venn Farm, going north uphill, it soon became deeply sunken and damp, evidence of a winter-bourne when the land was flooded by the rains. Sticks were jammed into little beaver dams, and the plants of stream banks, brooklime and water mint, grew in profusion, as well as various sedges. Further up the lane we found ourselves walking between ‘steep, high banks reaching to fifteen or twenty feet, with the hedgerow trees growing along the bank’, as described by Household. To our right was a grazing pasture, rising away up to a rounded down, and to our left the land fell away steeply in other grazing fields, with a double hedge of thick hazel, ash, blackthorn, sallow and holly, with here and there an oak tree or a massive ash.

Towards the high point of the lane, the going became harder than ever, as the brambles, bracken and ‘shoulder-high nettles’ closed in from either side in a deep, dark tunnel. We persevered, and came to a place beside a huge, slightly ragged ash tree with a trunk some twelve feet in girth. The bank wall of the lane to the east here was fully eighteen to twenty feet, and to the west the hedge was so dense that it would be possible to sit within its cover all day observing the comings and goings in the valley below without ever being seen.

Roger Deakin: Notes From Walnut Tree Farm

We walked up Venn Lane between high hazel hedges and statuesque oaks to Venn Farm. If we’d taken the path on the left, like Deakin and Macfarlane before us, we could have been gone for days. But we continued to the right.

There was a notice for a permissive path, tempting us off course, but we kept on past North End Farm, climbing up through steep pasture, with a panoramic view behind us to Langdon Hill and a glimpse of the sea beyond.

Ahead of us was a distinctive clump of small trees on Jan’s Hill, a sign that we should turn right and continue into another smaller kind of holloway.

And another in the bank along the way.

Before long we were totally submerged in green. I thought of a favourite little painting by Jelly Green called Darsham Ditch. It was painted at the beginning of the first lockdown, when no-one was going anywhere. All we had was right in front of our eyes. Jelly came out of her house and sat in a ditch and painted just what she saw.

Writing in 1938, the painter Paul Nash spoke of the ‘unseen landscapes’ of England. ‘The landscapes I have in mind,’ he wrote, ‘are not part of the unseen world in a psychic sense, nor are they part of the Unconscious. They belong to the world that lies, visibly, about us. They are unseen merely because they are not perceived; only in that way can they be regarded as invisible.’

An artistic tradition has long existed in England concerning the idea of the ‘unseen landscape’, the small-scale wild place. Artists who have hallowed the detail of landscape and found it hallowing in return, who have found the boundless in the bounded, and seen visions in ditches.

Robert Macfarlane: The Wild Places

This landscape is beautifully immersive, we can see hillforts on the horizon and cobwebs under our nose, and know that both are intimately connected.

We come down off Henwood Hill and find ourselves back at Quarry Cross.

There’s a brief view of Colmer’s Hill ahead of us before we dive back down again into Shute’s Lane and see it all rewound in reverse. Both sides now. Back to front and upside down, and all the way there and back again…

It’s a gallery of graffiti and a tunnel of green light. I don’t go for tattoos but I love carvings. I should’ve carved a tree for Jazmin but something tells me she’s already here. It’s a floating world, I breathe it in and I breathe it out.

And the road descends through fern banks and dappled light, shadows and delight, day and night, blindness and sight, never wrong but always right.

All the way back to Symondsbury where we started from, and ending up at the Ilchester Arms for a late lunch. Thank you.

※

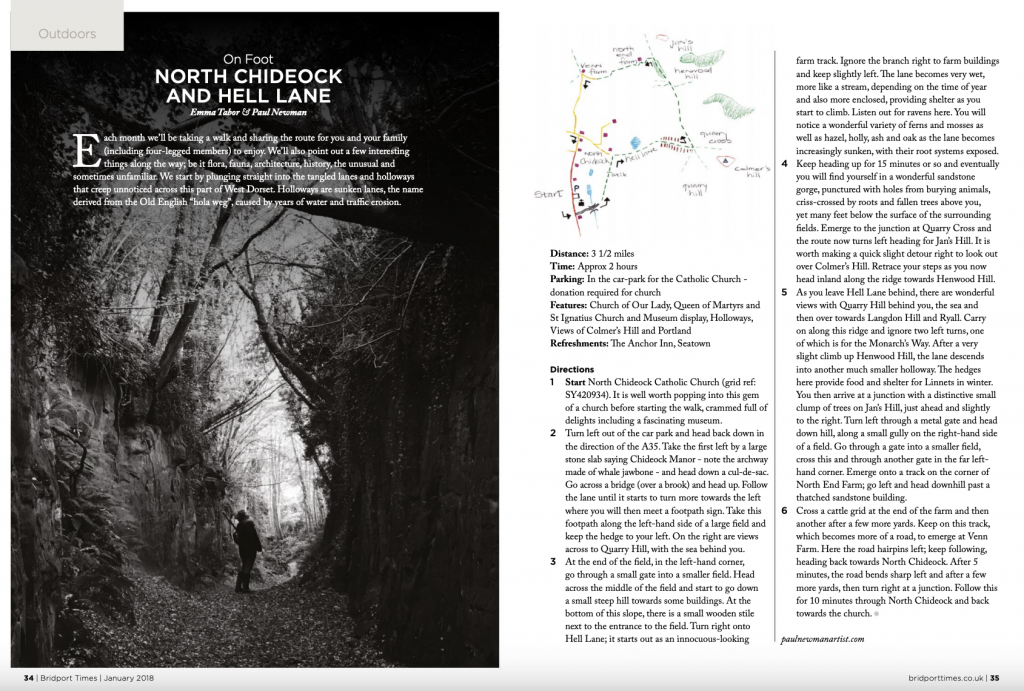

This was another walk suggested by Paul Newman. Thank you. We went around in reverse and added a link to Symondsbury.

※

Thanks to Robert Macfarlane and Roger Deakin for dreams and inspiration.

※

And thanks to Liz Somerville for setting us on the right track.

※

Please also see Holloway and Deep Lanes & Holloways.