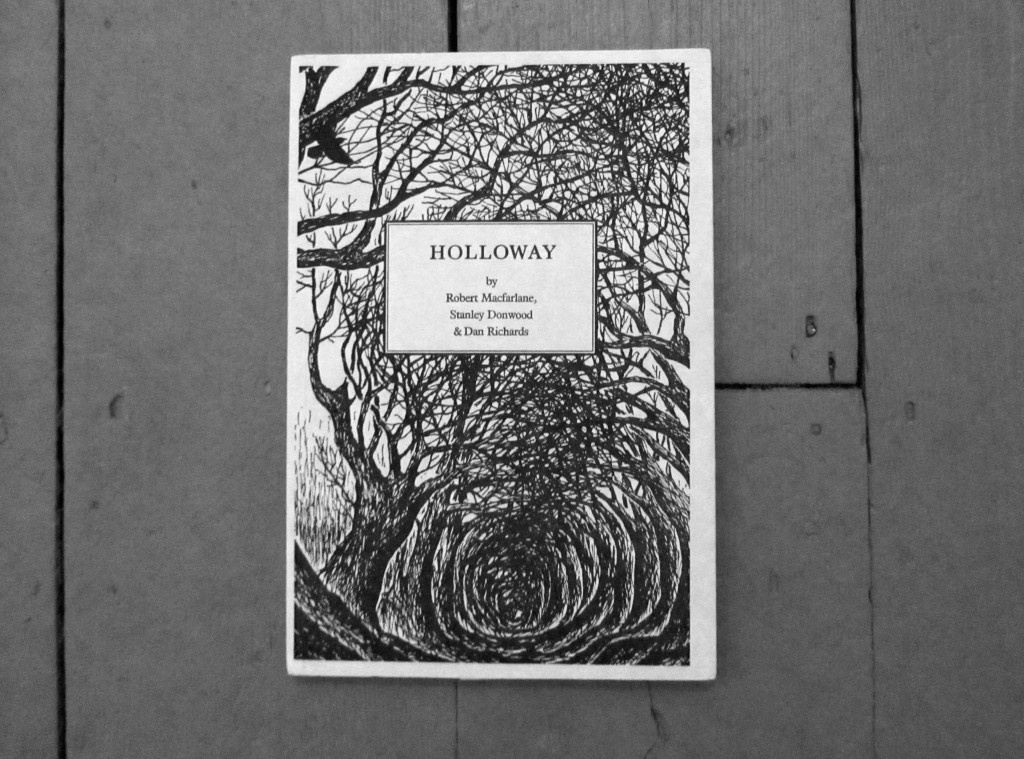

One of the many highlights of our recent trip to Cornwall was one that I took with me. Just a couple of days before we left London I received a copy of Holloway, a book by Robert Macfarlane, Stanley Donwood & Dan Richards. I kept it unopened in its Jiffy bag with Dan’s handwritten label and best wishes until we arrived, so that it became a part of our holiday. Inside, when I finally opened it, was a beautifully printed and illustrated book that told of the search for an ancient Dorset holloway, previously visited by Macfarlane with Roger Deakin. They were looking for the hide where the hero of Geoffrey Household’s novel Rogue Male went to ground. I’m not sure which I knew first, Household’s book or the film with Peter O’Toole. The abiding feeling was not so much of threat but of the safe harbour to be found beneath trees.

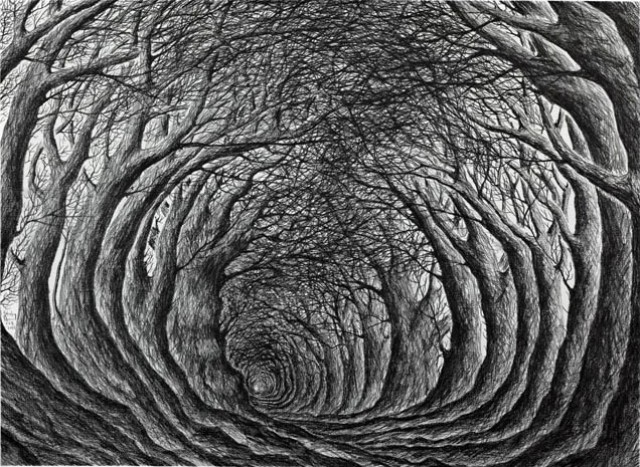

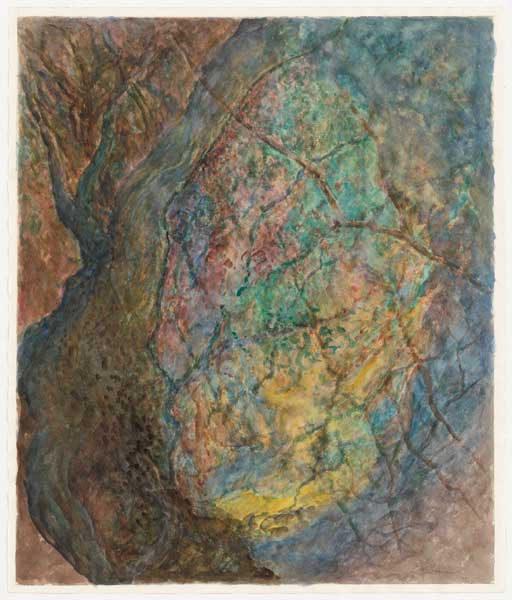

This image is from Slowly Downward, Stanley Donwood’s website.

Greenways, droveways, stanways, stoweys, bradways, whiteways, reddaways, radways, rudways, halsways, roundways, trods, foot-paths, field-paths, leys, dykes, drongs, sarns, snickets, bostles, shutes, driftways, lichways, sandways, ridings, halter-paths, cart-ways, carneys, causeways, here-paths – & also fearways, danger-ways, coffin-paths, corpseways & ghostways.

Inspired by the book I started looking for holiday holloways. Since Cornwall is mostly granite and the Lizard, which was where we were staying, is mostly serpentine, both of them hard and unyeilding, there were few of the Dorset type of worn and eroded holloways. Cornwall’s sunken paths are formed mostly by high banks and hedges, but they still give that protected sense of being sheltered by the landscape, immersed in its embrace and dappled shade. Their depths seem emphasised by the expansive views beyond, the contrast between the intimate and the distant.

This green frame was in the woods below Kestle Barton, one of three we encountered on our walk to Frenchman’s Creek. It describes a site selected for special attention, a green entrance to a green corridor, reduced to two dimensions. The threshold to an unborn holloway. There was a much older holloway at Trelowarren, where we found the Halliggye Fogou, an Iron Age complex of underground passages, dark and inhospitable but a welcome roost for hibernating Greater Horseshoe Bats.

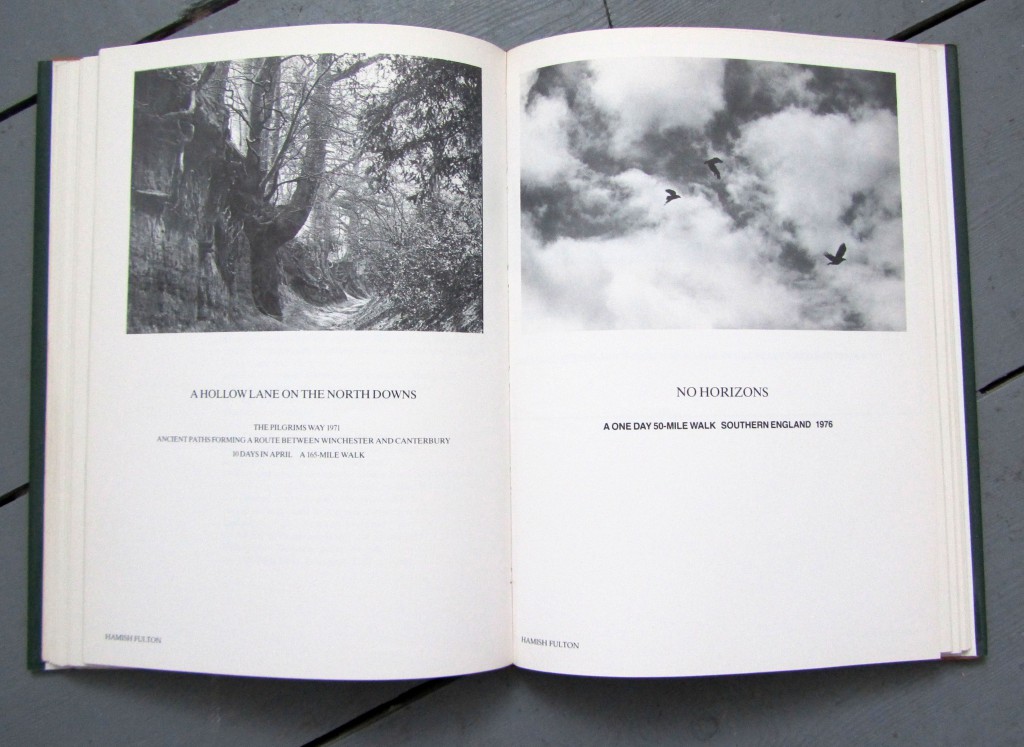

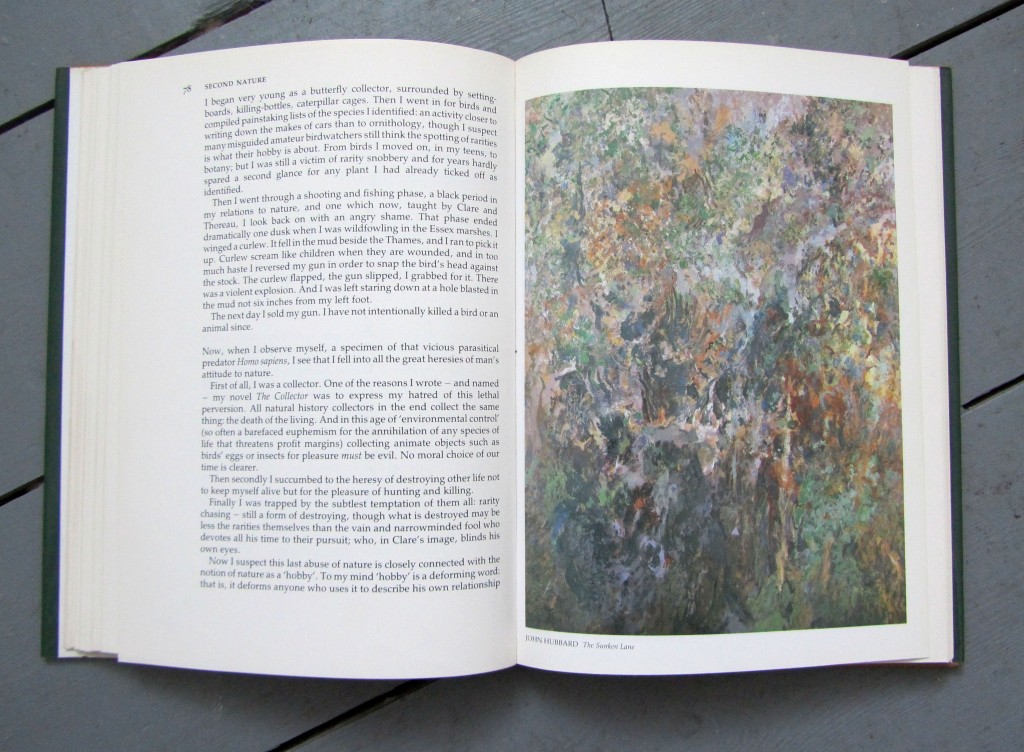

Then I remembered Second Nature, a book published by Common Ground in 1984. It was a collection of work by artists and writers and also a memorable exhibition in Covent Garden. There was a beautiful photograph & text piece by Hamish Fulton, A Hollow Lane On The North Downs, and a painting by John Hubbard called The Sunken Lane that was so inviting I just wanted to climb inside.

I wondered if this painting could perhaps have been inspired by the same holloway that originally inspired Geoffrey Household. When I asked John about it he said:

I’m afraid I don’t know which one GH had in mind but my impression, on reading his book years ago, was that the hero concealed himself in hollows round the edge of the Marshwood Vale which is close to Chideock. I would guess he had in mind the ancient hill forts of Lambert’s Castle or Coney’s Castle. The deep lanes I have been excited by are mainly nearer where we live, although there is a fine one in the village of Symondsbury which rises to the rim of Chideock Valley.

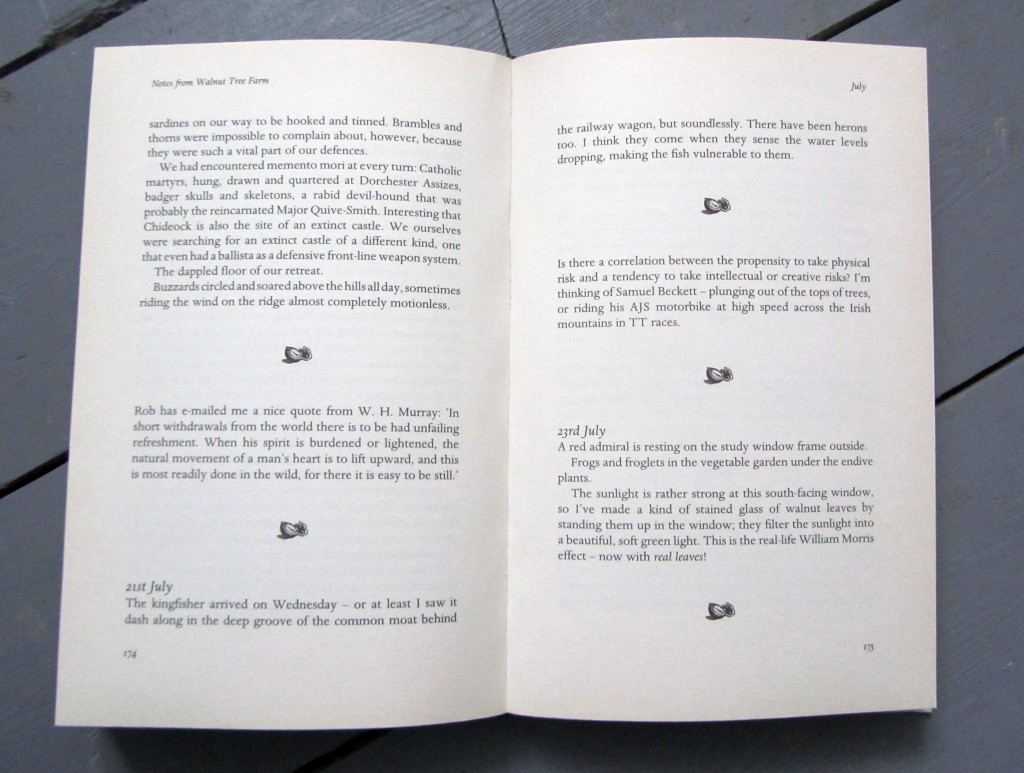

Then I went back to read Roger Deakin’s account in Notes From Walnut Tree Farm:

We bought a map from the village stores and drove up to North Chideock, where we left the car in the leafy, shaded car park of the Catholic Chapel of Chideock Manor. It is a hidden, well-wooded, secluded place…All its traditions relating to the Chideock Martyrs, the Catholic priests, are about hiding, outlaws, covert activities…We…set off up the hill through the village towards Venn Lane…it soon became deeply sunken…Further up the lane we found ourselves walking between ‘steep, high banks reaching to fifteen or twenty feet, with the hedgerow trees growing along the bank’, as described by Household…Towards the high point of the lane, the going became harder than ever, as the brambles, bracken and ‘shoulder-high nettles’ closed in from either side in a deep, dark tunnel…The bank wall of the lane to the east here was fully eighteen to twenty feet, and to the west the hedge was so dense that it would be possible to sit within its cover all day observing the comings and goings in the valley below without ever being seen…Household, with his interest in concealment, thinks unconsciously of Chideock and the martyrs hiding in their natural bolt-hole. And the badgers, persecuted and in hiding underground too – a topical touch. Even the mason bees made little burrows there in the wall of the lane.

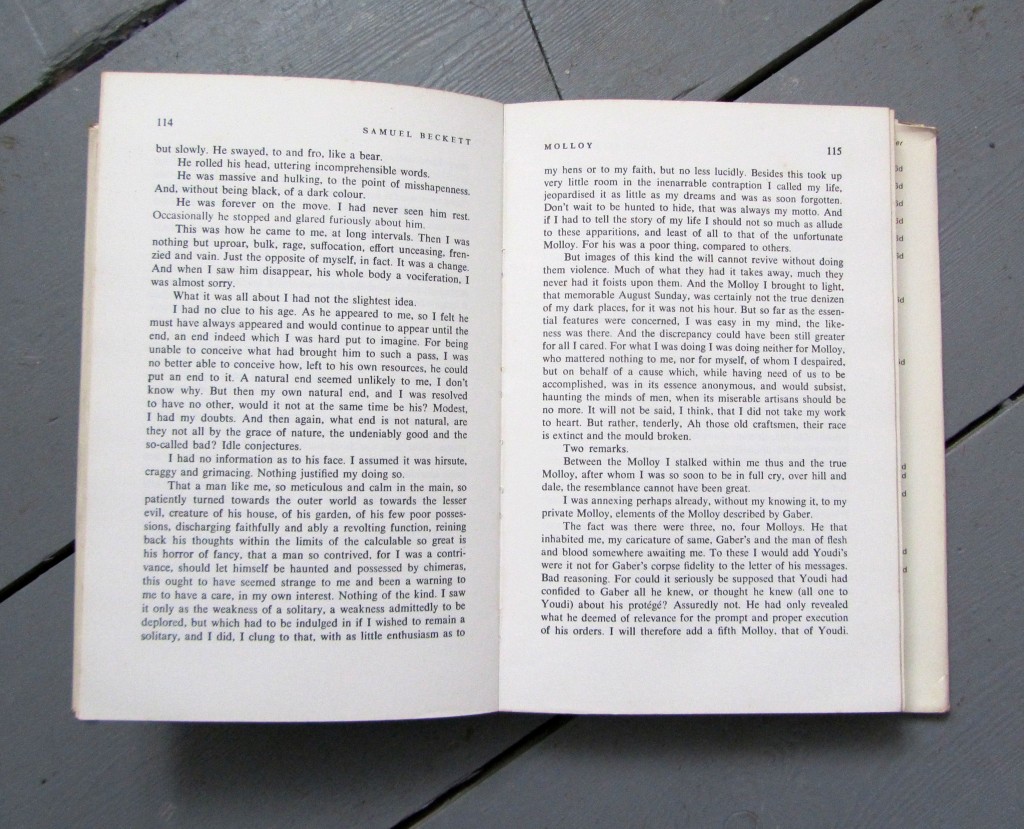

It’s a happy coincidence that on the next page he finds himself thinking of Samuel Beckett. Moran, the stalker, in Beckett’s novel Molloy famously says:

Don’t wait to be hunted to hide, that was always my motto.

I have never stopped to think about what holloway means before…tsk tsk. Really interesting. There are a couple of herds of Traditional English Herefords with the prefix Holloway too. Think I’ll be putting in an order for this book, there’s a birthday coming up!

I know of a holloway near the Cross and Hand in north west Dorset, up a steep steep hill and through a dying, moss-covered wood up from Batscombe. Very bleak place in winter. Even in summer the world looks very far away. I know Porthbeor as well, in the Roseland peninsula – one of the photos above. Pretty well all the roads are holloways…. The book looks amazing.

Thanks Tim. One of these days I must explore Dorset’s sunken lanes. There was a very good pub near where we stayed in Cornwall called Trengilly Wartha that was only accessible through deep sunken lanes.