What first strikes you about these Ice Age objects, suspended on transparent plastic stands in glass cases amidst crowds of 21st-century humans, is that they are absolutely tiny. The largest works are approximately the span of a man’s hand, the smallest the size of a child’s fingernail. For a big show it’s an intimate experience. There’s a lot of squeezing about, bending down and peering in, the peculiar sensation of having to adjust your perception to match their scale, as if squeezing yourself down through the same narrow aperture that leads to the wonders of Chauvet and Lascaux. What you’re experiencing is time travel. You adjust yourself to the conditions, and when you become accustomed to what you see, it’s as if you’re looking back to your own time through the wrong end of a telescope, the one that makes everything far away but pin-sharp.

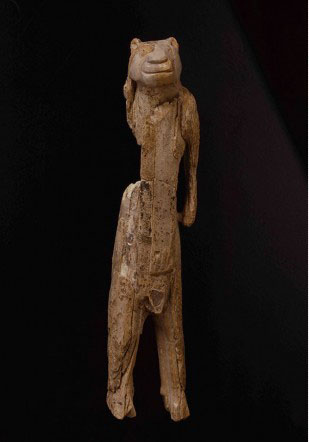

The art is recognisably of our making as an imagining, fashioning species, and yet so remote from us in time. But that thread of recognition is very long, very fine and very strong. The first figure you see is the Venus of Lespugue, the pregnant woman that astonished and fascinated Picasso. Beside her, in another glass vitrine, is the famous Lion Man. There is another, tinier Lion Man, and a one-armed puppet man, from the grave goods of what may have been a shaman – but the majority of human figures here are women.

Obese, pendulous-breasted, birth-giving women; women in the very moment of birthing, kneeling, the crown showing; young women in their prime with high breasts and thin waists; women in early pregnancy, their hands melting over their small bellies. They are acutely and beautifully observed; there is one head with distinct facial features – a drooping eye, a twisted mouth; on others you feel the weight of the heavy buttocks, the folds of fatty sexual flesh, the deep furrow of the genitals; they feel at once particular and universal; a woman, and all woman (we cannot say if they were fashioned for or by women or men). They are observed and conjured with the same kind of relish and intimate attention given by these artists to the depiction of animals.

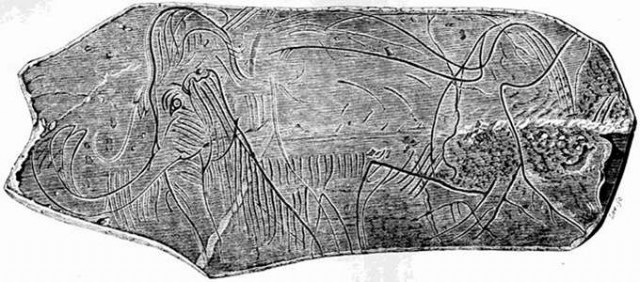

And there is a lot of wildlife – a lion in mid-leap; two reindeer in midstream, the male swimming behind the female, nose to tail; water fowl, barely bigger than a fingernail, but you sense its flight trajectory as if you were following its arc across the sky. There is an extraordinarily beautiful bison cow, in which the sense of mass and movement is vivid enough to stop you in your tracks; you feel its life force moving through the stone, and that force is mysterious now as it was then. A mammoth drawn on a mammoth’s tusk pulls you up short. A mammoth. This is art drawn from life. This is what the artist saw. It gives you a sense of perspective.

You feel like you’re at the fountain head of significant forces. What those forces are remain a mystery, or an illusion, because we still cannot understand consciousness, or why we must represent what we see and feel, or why we make symbols and invent metaphors, like men with lion’s heads, or why one of our species sat down and drew a mammoth on a mammoth bone. Did it just happen, like a cat sitting down to draw a dog? As your eye accustoms to the faint scored lines etched into its surface, you do feel the image rise up into life as you recognise it, as if it’s animated by the act of being looked at. It feels like direct contact, as if the artist’s breath is at your neck, the weight of that extinct body mass moving slowly to life, an image clarified from cloudy waters, from the narrow corridors of human perception. What is it but time travel? You’ve made something ancient come alive. Science tells us about the observer effect.

It’s curious that many of these masterpieces of the prehistoric were smashed once they were made. There are a number of tiny lions’ heads, baked in clay, taken from a site where thousands of such animals were fashioned, and then fired when wet, so that they exploded in the kiln. The destruction of the art was seeded in the making of it. Many of the pregnant women were smashed, too, once they were done with. What point, exactly, had been reached when they were done in? What trigger was being released? Was the meaning in the making more than the viewing? Big questions, no answers, but a powerful sense of connection. It is said that when Picasso saw the art of Lascaux he exclaimed: “We have invented nothing new!” We leave this exhibition with a modified sense of our own scale. This is art with a purpose, and when you leave, the images leave with you. You leave together feeling incredibly alive.

*The show ends on 2 June but for those unable to visit, the catalogue is highly recommended.

Tim Cumming / The Rowley Gallery

※

Tim Cumming’s Radio Carbon film poem explores the potency of prehistory and the motions of the deep past and the vertigo of deep time in the present day.

When cosmic rays strike the atmosphere they create the radioactive isotope carbon 14, which can be detected in living matter and decays at a fixed rate over many millennia. Radiocarbon dating is the method by which we measure prehistoric time, and with which our own detritus will one day be measured. The filmpoem Radio Carbon takes this transient yet permanent record of time as a personal metaphor, fashioning a hypnotic journey into the human past, from the neolithic to the present moment. It’s a film with eternity at its centre, the vastness of space at its core, and a reverie of images clustering to the lens like the flashing in a stranger’s eye.

Both beautiful again. I love the tiny figures and then the poem, but I’m not sure about the man’s voice. Is the poem published anywhere?

Dear Stephanie, I’m afraid the poem only exists in the film-poem form but if you have a contact email I would be happy to send you a PDF of the poems. Glad you liked the blogs, the figures and the poem, it is a stunning show.

Dear Tim,

Thank you, I would like that. The film was exquisite in places too but there was so much music in the words that I think the reader did not quite capture. Perhaps the voice was too harsh for the dream-like quality of the rest.

Have you seen Humphrey Jennings’ film ‘Words for Battle’. Not that it is quite the same sort of thing but in it Olivier reads poems by Blake and Kipling, among others, over images of World War II. In that he reads part of Kipling’s poem that begins, “Nobly, Nobly, Cape St Vincent”, against images of sunset. It is perfection, something other in itself. I will try to post it on here.

http://youtu.be/nnZ5ExcXMxo

Here is a link to ‘Words for Battle’ (I hope!).

Thanks Stephanie, I’ll forward your email address to Tim.

Beautiful and fascinating Tim. I’m so glad I saw this show. I was mesmerised by the Venus of Lespugue. So many treasures it was breathtaking. Perhaps my favourite was this multiple drawing of horses, one on top of another like a palimpsest, made me think of those Muybridge animal locomotion photos.

Yes it’s a stunning drawing. And that sense of animation in the bison and also the lions in Chauvet cave. One feels the sense of hypnagogia – involuntary, animated, hologram like images on the verge of waking and sleep …

Dear Tim, I just received this email –

Hi Chris

Tried to post this comment (below) but it was rejected – maybe because I’m on a phone rather than computer?

I’m abroad now until Monday but if there’s any way you can post it for me then please do so.

Cheers, Susie

‘Grateful for your words & wisdom Tim, enabling seeing without jostling. I may make it to the BM now you’ve opened the door. Film poem fantastic.’

Susie Pocket

Dear Susie, I hope you get the chance to see it, and so glad you liked Radio Carbon too.

The show also has 20th century works – the Brassais were a good addition, though the others didn’t have much effect for me. And a rather hypnotic film of some of the Chauvet cave art