The plateau of Cauria, 15 kilometres south of Sartène and 2 kilometres from the coast, is home to three historic sites emblematic of Corsica: the megalithic statue-menhirs of I Stantari and Renaghju, and the dolmen of Funtanaccia.

For the origin of sculpture, these monumental figures are as important as the cave drawings of Lascaux and Altamira are for the origin of painting. When you look at one, you know it represents someone — someone to whom you could give a name.

We left the car in the shelter of a magnificently gnarly old cork oak and followed the arrows

down the hot dusty lane to a second cork oak

and eventually to a third cork oak.

Quercus suber, commonly called the cork oak, is a medium-sized, evergreen oak tree in the section Quercus Cerris. It is the primary source of cork for wine bottle stoppers and other uses, such as cork flooring and as the cores of cricket balls. It is native to southwest Europe and northwest Africa. In the Mediterranean basin the tree is an ancient species with fossil remnants dating back to the Tertiary period.

The tree forms a thick, rugged bark containing high levels of suberin. Over time the cork cambium layer of bark can develop considerable thickness and can be harvested every 7 to ten years to produce cork. The harvesting of cork does not harm the tree, in fact, no trees are cut down during the harvesting process. Only the bark is extracted, and a new layer of cork regrows, making it a renewable resource.

As a pyrophyte, this tree has a thick, insulating bark that makes it well adapted to forest fires. After a fire, many tree species regenerate from seeds (as, for example, the maritime pine) or resprout from the base of the tree (as, for example, the holm oak). The bark of the cork oak allows it to survive fires and then simply regrow branches to fill out the canopy. The quick regeneration of this oak makes it successful in the fire-adapted ecosystems of the Mediterranean biome.

The ancient site of I Stantari contains two rows of standing stones: eleven remain upright where thirty once stood. They stand like stone phalluses, the simplest of figurative sculptures, two with carved faces, a congregation of stoic survivors. Their essential purity was sought by many modern artists; I see echoes of Constantin Brancusi and William Turnbull, and perhaps also Antony Gormley.

This photograph is courtesy of Le Patrimoine de Corse.

A little further and we arrived at Renaghju, a confusion of stones situated in a shady copse.

A community established itself here around 5700 (Neolithic Period), up against the rocky outcrop of ‘Punta di u Grecu’, near a spring and a still water pond. In 2006 a 20 m² rectangular shaped dwelling was identified (D’Anna’s excavations), with wooden posts, earthen walls, hearths and braziers. Two areas with anvils were located (for knapping obsidian, quartz and flint). The pottery – some of the oldest discovered and notable for its cockle shell imprint decoration, is known as Cardial Ware (remains on display in Sartène Museum).

After a period of temporary abandon, the site was occupied anew. Some 60 “petre zuccate” (raised stones or menhirs) existed around 4500 BC, rising in number to 180 towards the first millennium BC. This is the first time, in Corsica, that it has been possible to establish a precise time for such a site. Elsewhere, shovels or metal detectors have despoiled the stratigraphy to little or no gain.

V Maliet, Chief Heritage Curator, Collectivité Territoriale de Corse

Beyond Renaghju we came upon the mightiest of all the cork oaks we encountered that day.

A magnificent specimen that reached down to embrace us.

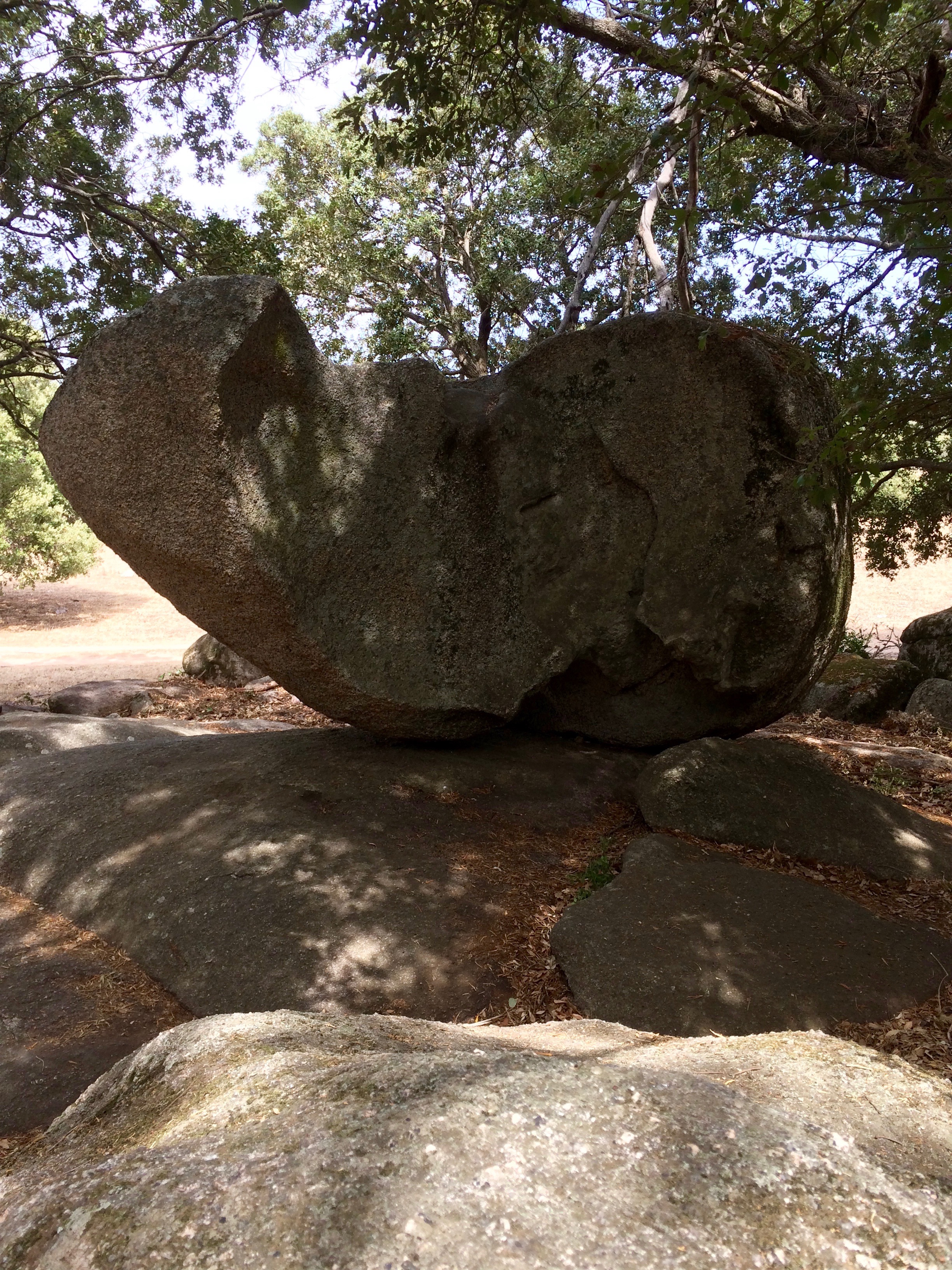

Over the bridge and into the oak grove, this time holm oaks growing among the boulders.

It is a natural sculpture garden.

Then up the hill to Funtanaccia dolmen.

Sitting atop a naturally occurring hillock, this is Corsica’s best known and preserved dolmen. As well as making a deep impression on people, it served as a place to pay one’s respects to the deceased. A collective burial chamber, the roof consists of a single stone slab (3.40m x 2.90m) placed on 6 vertical stones (orthostates: 3 to the west, 2 to the east, 1 to the north). Built using two different types of granite (coarser grained for the vertical stones or orthostates, finer for the stone roof), it dates from the second millennium BC (the first megalithic tombs date from around 3000 BC). Running in a north-south direction, the funeral chamber was sealed by a stone slab, although nowadays only the threshold remains.

V Maliet, Chief Heritage Curator, Collectivité Territoriale de Corse

Known to locals as Stazzona del Diavolu (the Devil’s Forge), the Fontanaccia Dolmen is considered the best-preserved dolmen in Corsica. Nearly two meters high, with six huge granite blocks supporting its great stone roof, it was once entirely covered by an earthen mound, long since eroded away.

Scattered across the thinly populated hills of southwestern Corsica are numerous megalithic sites dating from as early as the fifth millennium BC. Little studied, the identity of their builders and purpose remains mysterious. A comparison to similarly shaped prehistoric structures in continental Europe suggests the Corsican alignments of standing stones, or menhirs, were used for astronomical observations and the chambered mounds, or dolmens, were used for ceremonial or healing purposes. A common misconception perpetuated by tourist guidebooks is that the human skeletal remains found inside and around a few of the dolmens indicate their use as funerary chambers. There is, however, no archaeological evidence to support this notion. The stone structures are far older than the bones found inside some of them. An ancient culture built the dolmens, while more recent people used them as convenient, already excavated places suitable for burial of the dead.

Martin Gray, Sacred Sites of Corsica

The true reason for these structures, the dolmen and the alignments of menhirs, remains a mystery. But in a place so littered with rocks and boulders, man’s natural inclination to tidy-up and domesticate his environment must have played a large part in the arrangement of these stones.

We followed the arrows back to the car under the magnificently gnarly old cork oak.

Fantastic.

And lots of twig saints lurking in the bushes.

Wow… I must visit this place!

Yes, you’d love it. Hooded crows, red kites, choughs and jays.

I’m impressed with how peaceful and natural the place seems to be. It’s nice to be able to enjoy something so ancient outside the shadows of modern sprawl.

Not much modern sprawl anywhere in Corsica that I could see. Just wild and ancient. L’Île de Beauté!

Interesting the dolmen was known as The Devil’s Forge. The long barrow known as Wayland’s Smithy on the Ridgeway near White Horse Hill might have similar myths that are linked.

Looks like the devil had his irons in many fires!

It looks fantastic Chris, next year perhaps.

Some wonderful winding corniche roads with spectacular views around every corner. I think you’d like it.

What an amazing place! Definitely on my wish list… 🙂

Cheers Jim, thanks for looking.