I suppose that’s a bit of an exaggeration, we didn’t stay overnight, but it sounds better than two visits or two day trips to Epping Forest. The first was a week after Easter, on St George’s Day, inspired by blogposts and tweets about holloways, I wondered what’s the closest thing to a holloway in Epping Forest? And so we went up to Jack’s Hill and walked to the western edge of Ambresbury Banks.

Ambresbury Banks is one of two ancient earthworks in Epping Forest. It is believed that both Ambresbury Banks and Loughton Camp were built circa 500 BC and were used as animal folds in times of attack from other tribes, or as look-out posts and boundary markers between the two neighbouring tribes of the Trinovantes and the Catevellauni. Evidence suggests that they were in use until after the Roman invasion.

The earthen banks enclose over four hectares of land. When first built the banks would have been about three metres high and the ditches outside them three metres deep. They would have been built by hand with wooden or bone tools used to scrape the soil.

According to local legend, Ambresbury Banks was the site of the defeat and death of the great British Queen Boudicca (Boadicea), at the hands of the Romans in AD 61. In recent years, that story has been disproved but Ambresbury Banks still retains a mystic and majestic atmosphere.

It’s also a bit of an exaggeration to call this ditch a holloway. It’s not very steep and it leads nowhere, just around in a circle to back here again. But cleared of centuries of leaf litter, with a timber revetment above the bank, it might almost be a canyon. Though today it’s more like a shalloway.

We walked across the centre of the camp, now the line of the parish boundary between Epping and Waltham Abbey, the beech mast popping and crackling under our feet as if it were on fire, just as two riders broke cover on the far side, their horses galloping at high speed down the Green Ride.

As the rhythmic echo of their clattering hooves subsided and silence prevailed, I dreamed this was perhaps a holloway after all, worn down by the passage of time.

The idea that generations of feet and hooves and wheels could literally carve a hollow way should humble us. Oliver Rackham cited 38 mentions of ‘hola weg’, hollow ways and hollow paths, in Anglo-Saxon charters. These and the names Holway and Holloway, as in the Holloway Road, north London, are likely to signify extremely ancient routes.

Sue Clifford & Angela King: England In Particular

But the shadows of the trees, their branches not yet cloaked with leaves, accentuate the curves and slopes of the banks and the ditch. Most of them are beech pollards, some might even suggest hands, their branches become fingers, a reminder that Ambresbury Banks was in fact not eroded by feet but made manually, excavated by countless digging hands. So why not dream a tree of hands instead?

Then in the distance, a dark triangle of black earth with a shining white circle at its centre. An Anish Kapoor in the forest. But as we approached it was revealed as the upturned root ball of a fallen tree.

The trees here are warm and welcoming. Over the years many visitors have been moved to leave their mark, and taken away a blessing from this place. I stepped inside the arms of this coppiced beech and looked up, and discovered a new map of the sky above Epping Forest.

I don’t usually go for tree anthropomorphism, but this pollard, with arms upstretched, twisting torso and pumped-up muscles, seemed to suggest the posturing stance of an overdeveloped bodybuilder.

We left the precincts of Ambresbury Banks and walked on, following the circuit around Epping Thicks towards Kemp’s Lawn, where we came upon the lower and upper ponds, also known as the Pizzle Pits.

U WOZ ERE

At Bell Common the path skirts the edge of the Epping Foresters Cricket Club, and their unique cricket pitch. This idyllic field was laid down directly above the M25 motorway, sunk into a cut and cover tunnel below. Village green leather on willow disguising metropolitan infrastructure pollution.

We were on Crown Hill Bridge, the very spot to which Tony Sangwine (the Highways Agency landscaper) had brought us – when he wanted to show the best the motorway could offer. Sangwine’s vision is not so far removed from the builders of the Ambresbury Camp. ‘I think we’ve done a good job in treating the road here. Not just the planting but also the alignment. The way the earthworks have been blended. A combination of good engineering practice, good landscape architecture, good horticulture.

The M25, if it is ever to work as archaeology, as a circuit that combines ‘good engineering practice’ with good faith, will depend on the quiet labours of men like Sangwine, practical transcendentalists. Think of the motorway in terms of Maiden Castle or Avebury, earth engines, machines designed to provoke enlightenment. The hoop of continually moving light is a gigantic crop circle, visible from space. A doughnut of powdered glass. A winking eye.

Iain Sinclair: London Orbital

From here the path looped back, altering our course from northeast to southwest, back to Epping Thicks, where fallen branches, writhing like a nest of snakes, are welcomed back down to earth by the tender green shoots of new ferns unfurling beneath them.

A little further and we suddenly realised we were being watched. In the near distance, hidden in a thicket of holly, four roe deer stood stock-still and watched us pass. As I adjusted my camera for a better shot, they turned and disappeared into the forest.

Animals make tracks, humans make paths. But paths in forests model the complexity of their surroundings. They ‘branch’, then they branch again. The artist Olafur Eliasson… tried to capture some of these compacted meanings in his 1998 installation ‘The Forked Forest Path’, which turns the art gallery into a wood, branches rising up round the path to make a tunnel through which the viewer walks… maybe it catches a whiff of the panic of feeling lost. But the clean lines… seem to me to work against the messy physicality of the path… something which, harking back to the word’s Germanic roots, is ‘trod’. In that sense, Richard Long’s famous and self-explanatory ‘A Line Made by Walking’ comes closer to expressing this ‘pathness’, though in its monomania, its ramrod-straight intensity and the fact that it goes nowhere, it is in other senses not a path at all.

Another reading of Olafur’s work is possible. In the forest we are forced, again and again, to answer a particular question: this path or that? The forest becomes, in this way, a kind of physical representation of life, or at least those crises in life when a choice has to be made. Except on these paths you can always turn back… The title of the installation seems to contain an allusion to ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’, a story by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, in which, somewhere in a crazy nest of narratives, the ‘learned Sinologist’ Stephen Albert explains to the spy Dr Yu Tsun the true meaning of a novel of that name written by the latter’s ancestor: ‘In all fictional works, each time a man is confronted with several alternatives, he chooses one and eliminates the others; in [this work] he chooses – simultaneously – all of them. He ‘creates’, in this way, diverse futures, diverse times which also proliferate and fork.’ The author, Albert tells Tsun, has created ‘an incomplete, but not false, image of the universe’. The universe of any single human life, though, is not infinite, any more than an art gallery is. Whichever path you choose you eventually turn up in the same place. A dead end.

The path we chose was the Green Ride, past countless sentinel beech pollards, wayside guardians on our route by the Four Wantz and Long Running to Jack’s Hill and, after lunch at the Woodbine Inn, back home again, home again – Ah, but I miss the trees, and I wish that I were home again.

※

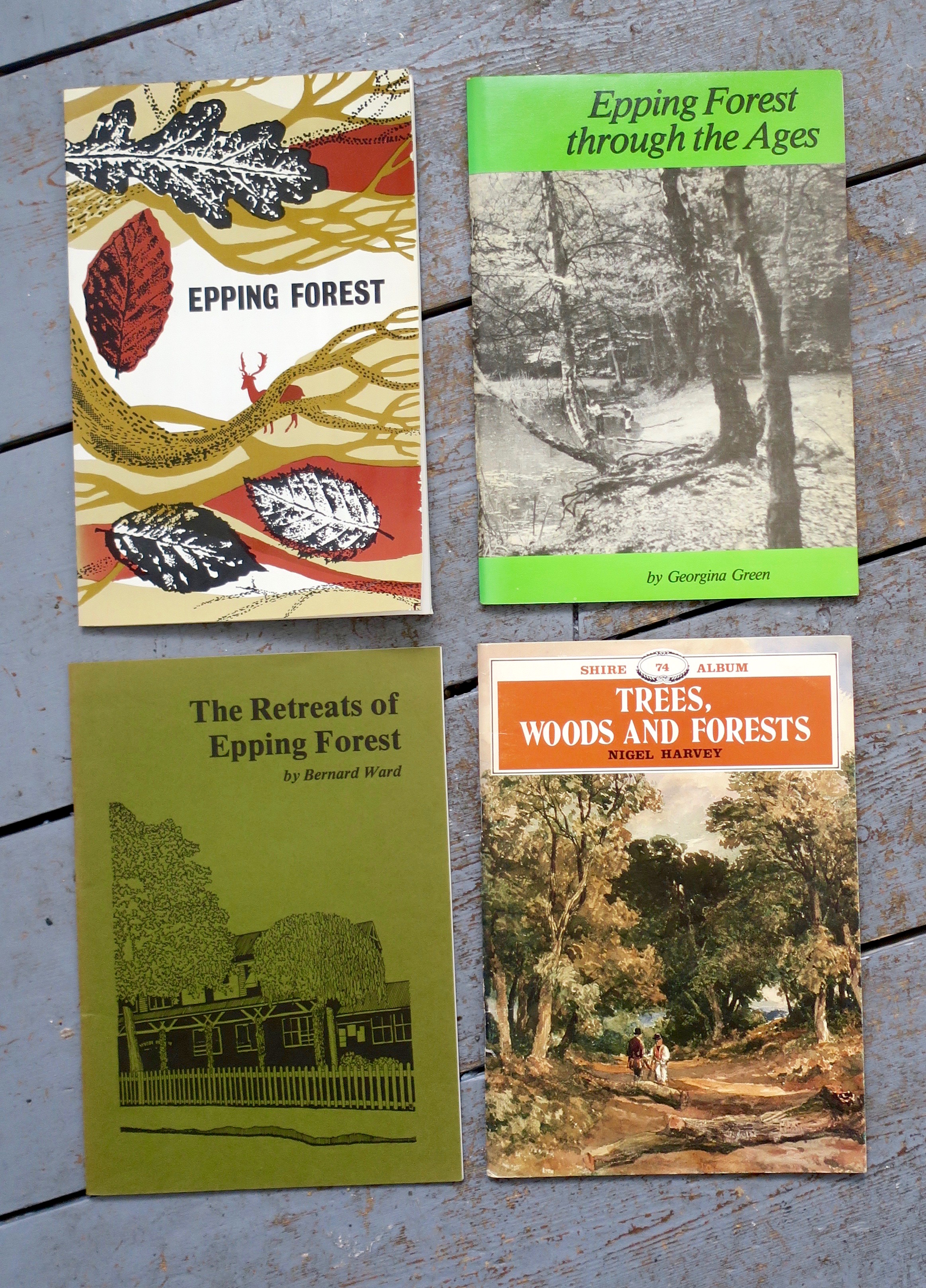

We returned a week later, on May Day, to a part of the forest not visited before. I’d recently bought a new map of Epping Forest and noticed a landmark tree that was not mentioned on my old map. It was marked as Qvist’s Oak on Warren Hill near the offices of Epping Forest at Warren House. By a nice coincidence this was just as I rediscovered a collection of pamphlets, hidden on the bookshelf since the early 1980s. One of them, called simply Epping Forest, a revised edition from 1971, was by Alfred Qvist, Superintendent of Epping Forest. The oak tree must have been named after him. It seemed like a good excuse for a return trip.

We came up to Buckhurst Hill and another cricket pitch, this one in a clearing of Powell’s Forest.

There are not many horse chestnuts in Epping Forest, it’s mostly beech, oak, hornbeam, silver birch and holly, so this sapling beside the cricket ground was a rare opportunity to view one from above.

The pride of [Epping] Forest is its hornbeams.

There is no larger forest of hornbeams in England,

nor perhaps in the world.

Nikolaus Pevsner: The Buildings of England

Ne’er cast a clout till May be out

Anon

As we approached Warren Hill I was on the lookout for notable trees. I’d not seen Qvist’s Oak before so I didn’t know what to expect. I wondered if it might be this old staghead. I left the path for a closer look and my feet quickly discovered that Warren Hill is riddled with ankle-twisting rabbit holes.

But then at the top of the hill there was no doubt. This graceful and statuesque tree had to be Qvist’s Oak. There was nothing else to touch it, standing in its own clearing, watching over its own neck of the woods, this is a most singular and distinguished pollard oak. A good excuse for a walk in the forest.

There’s a confusion of paths, some are named but many are not. There’s the Gas Ride, the Green Ride, the Three Forests Way, but we chose the path by the bluebells. On the way up it was empty, on the way back three women sat here, smack in the middle, soaking in the fragrance, bathing in bluebells.

We came by Strawberry Hill Pond and Earls Path Pond to the Green Ride and down to Debden Slade.

A grass hollow, in the heart of the woodland, which is now developing a crop of oak seedlings. On the northwest fringe (as also near Blackweir Pond) may be seen specimens of the wild service, a rare but typically indigenous forest tree, turning a fine reddish purple in autumn.

Alfred Qvist: Epping Forest

Over to our left, we felt the pull of Loughton Camp, hidden in the green depths, but we resisted its charms and pressed on to the junction with the Clay Road. Here again we were tempted to leave the path, this time for the Lost Pond (also known as Blackweir Pond), probably my favourite place in all the forest. Its an oasis of calm, a pool to reflect the sky in a circle of beech and holly. But today we passed by, down to Baldwins Pond and up to Baldwins Hill.

The Foresters Arms is a good place for a glass of Adnams, but proceed with caution. Last time we were here I found Margaret Thatcher lurking in the gents, so now I prefer to go behind a tree.

Baldwins Hill is also the name of the street that skirts the edge of the forest. Over the years it’s been home to some notable residents.

Ken Campbell (1941-2008) actor, director & playwright lived here.

Sir Jacob Epstein, sculptor, born 1880, died 1959, lived in this house from 1933 to 1950.

Muriel Lester (1884-1968) and her sister, Doris (1886-1965) peace campaigners and philanthropists lived and worked here.

Down the grassy slope and back to Baldwins Pond by the slippery route. It was the first time I’d ever seen anyone fishing here. There were two of them and according to the sign it was the closed season.

All the watercourses in the Monks Woods and from Broadstrood come together at a point on Green Ride known as Pig Corner or Bellringers’ Hollow. Thence they flow in one stream to form Baldwins Pond and then Loughton Brook, supplemented by other watercourses rising and gathering together further south.

Most of the ponds are stocked with fish to a greater or lesser degree, the public being at liberty to fish in all excepting where a toll is charged. This freedom to fish is, of course, subject to the bye-law against foul fishing and to the close season operating throughout the country. The Conservators have the power to impose closer control but hitherto it has not proved necessary to invoke it.

Alfred Qvist: Epping Forest

And then the rain started. The softly sussurating sound of raindrops falling on leaves, dripping to the ground in sensurround, louder and louder until they became a deafening downpour. I ran for the shelter of the trees by Loughton Brook but the sodden leaves offered little protection.

Sue carried on regardless, sensibly attired with waterproof hood, while I followed on behind, dodging from tree to tree, my corduroy jacket heavy and wet. We halted beneath Qvist’s Oak and the sun came out, the rain cleared and a rainbow appeared to bring us back home, my jacket gently steaming.

※

If you enjoyed this post you might also like

Ambresbury Banks / Epping Snow / In Epping Forest / Pulpit Oak / Chasing Golden Light

I did enjoy this thoughtful and attentive post. And such good portraits of trees.

Thanks for looking Jean, I’m glad you liked it.

More great photos & excellent description of An Outing! The bit about the holloways made me remember the camp where I grew up in Buckinghamshire. Camp Road in Gerrards Cross encircles what I was told was a Roman Camp, but your post makes me think it must previously have been a prehistoric enclosure, and asks for more scrutiny on my next visit.

Reading about the “pollard oak” I wondered whether, and how (not as in France), the forest had been used: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pollarding

Many purposes, it turned out, and now we have that dense bright canopy primarily as a respite, for men and trees, deer and bluebells, wonderful to see in May, when leaves are new. Thank you for sharing the day and what you saw, it will bear another read.

You might have guessed Warren Hill would be an ankle-twister, but sometimes we lose the clues of the old names!

We were here a few weeks ago, the leaves will be greener now, it’s different every time. Thanks for the Pollarding link, that pollard beech looks very familiar!

What a wonderful, informative, insightful post. I’ve known and loved this forest since childhood but you’ve given me an entirely new appreciation of it. Thank you so much.

I’ve been coming here since 1979 and it’s like I discover it afresh each time. It’s always fantastic.

Such a beautiful place. But in the second and third photos from the end, the apartment building seems an ugly intruder. Having said that, I suppose it is a nice place to live for people who enjoy nature walks.

I wouldn’t mind an apartment there, good access to the trees and views of the cricket. I like the way the forest infiltrates suburbia. We’re a crowded island so we must take our pleasures where we find them.

Thoroughly enjoyed this read. And thank you for the idea of visiting the pub The Woodbine – an excellent choice for a spontaneous Sunday lunch. I was inspired to investigate further and find your blog after reading Oliver Rackham (1976, Trees and Woodland in a British Landscape) who mentions the pollards at Epping: ‘I have found oak pollards in Epping Forest of only 50 inches girth which are at least 350 years old, having maintained an average ring width of 0.4 mm since 1729; this must be close to the slowest rate at which an oak can grow and yet remain alive’.

Thanks Rachel. I enjoyed reading about your Kali’s Wood.