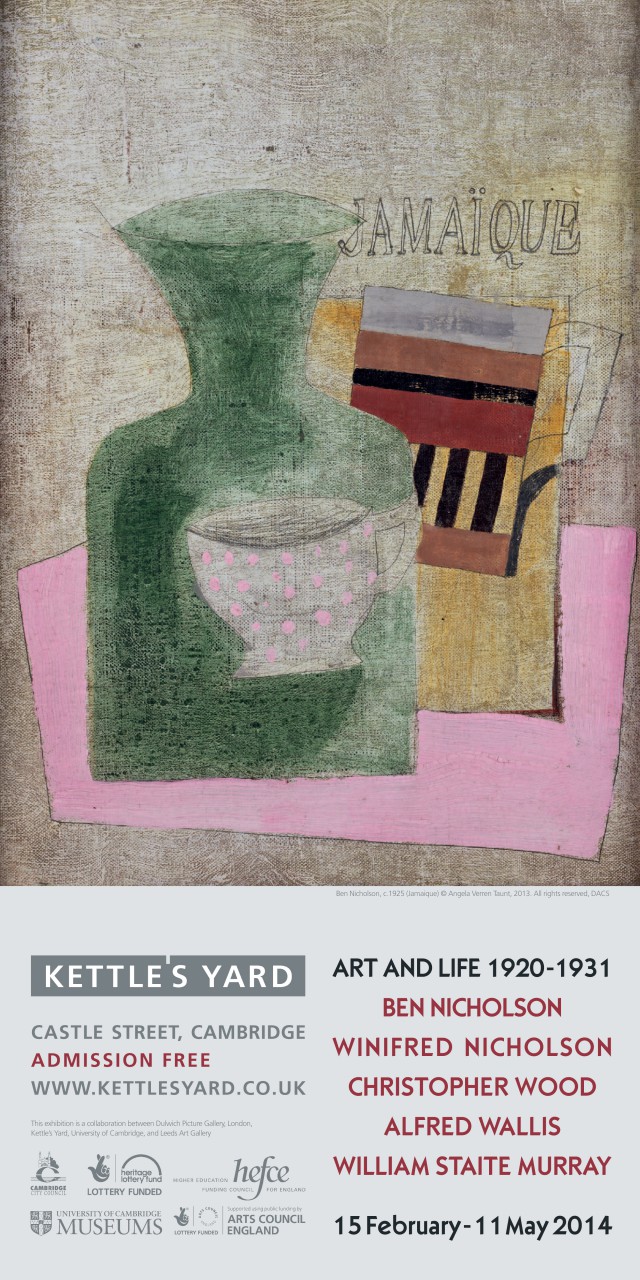

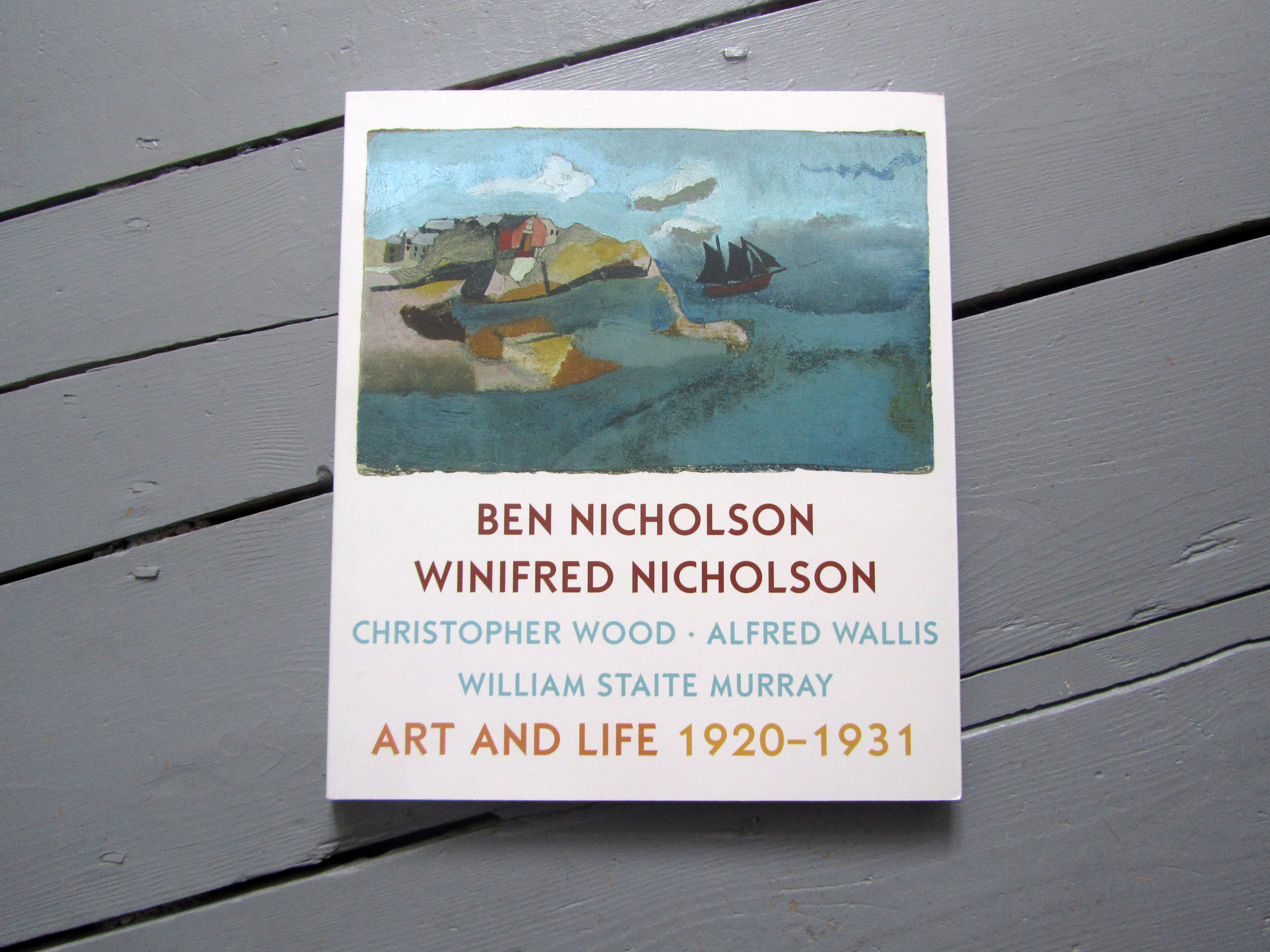

This painting by Ben Nicholson, titled c.1930 (Cornish Port), features on the cover of Art and Life 1920-1931, the catalogue for the exhibition at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, examining the artistic partnership of Ben Nicholson and Winifred Nicholson in the 1920s and their friendship and collaboration with Christopher Wood, Alfred Wallis and the potter William Staite Murray.

Inspired by each other, the Nicholsons experimented furiously and often painted the same subject, one as a colourist, the other more interested in form. Winifred wrote of her time with Ben –

‘All artists are unique and can only unite as complementaries not as similarities’.

The exhibition was a great invitation to visit Cambridge again, so we went up to Granchester for breakfast in the Orchard then walked alongside the river into town. It was a trip down memory lane. Seven years ago we came on a works outing from The Rowley Gallery and left our shadows here.

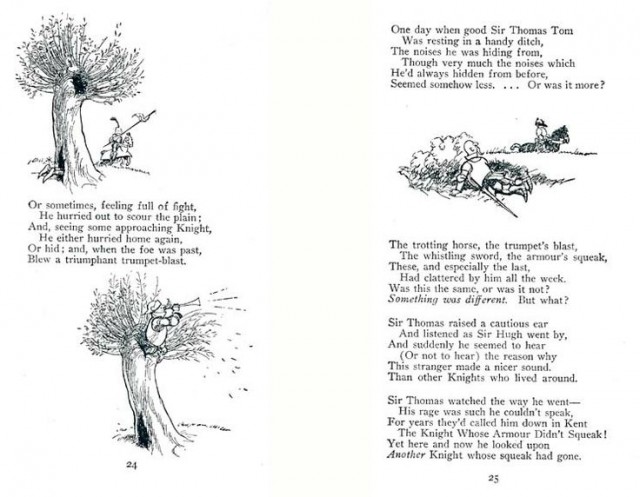

There’s something about these cracked riverside willows that always reminds me of E.H.Shepard, who illustrated The Wind in the Willows, but more memorable for this hollow tree from Now We Are Six.

We walked along the river through Paradise Nature Reserve and Sheep’s Green / Lammas Land to the Millpond, where the Granta, aka the upper river, reverts to the River Cam via the punt slipway.

It was here, thirty years ago, as we hauled our hired punt up from the lower river, that we were diverted from our intended picnic when Sue got a memorable monster splinter lodged firmly under her fingernail and we ended up at Addenbrooke’s Hospital for an emergency extraction instead.

This time we were welcomed into town by the cheers and applause of the Cambridge Half Marathon.

We came along King’s Parade by Great St Mary’s Church where once we saw Stephen Hawking in his time-travelling electronic wheelchair, being bustled along the cobbled street by his two female chaperones, late for an engagement at Gonville & Caius. We continued down past Trinity and St Johns, over Magdalene Bridge and arrived at Kettle’s Yard in plenty of time. The house is a time capsule.

※

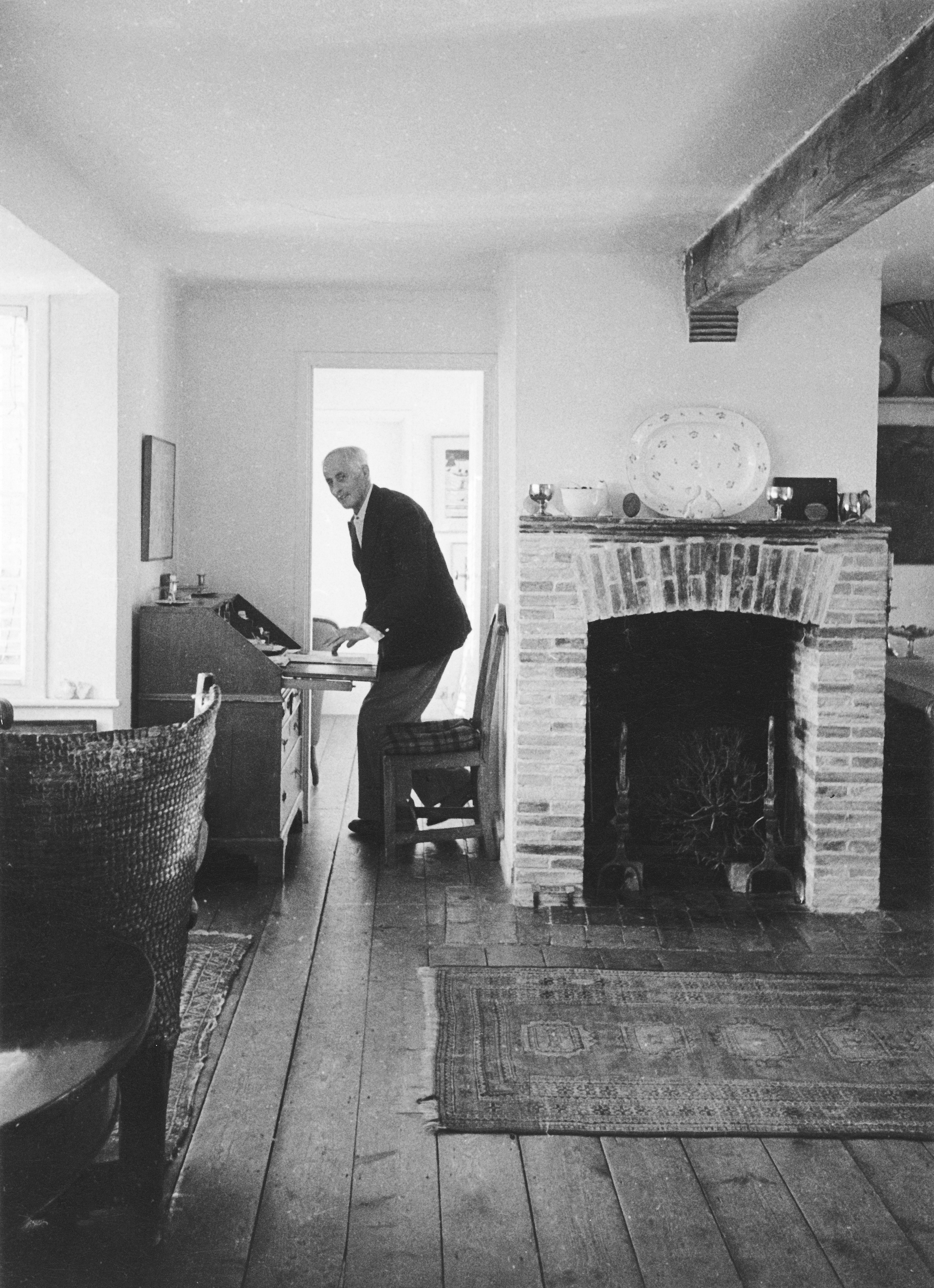

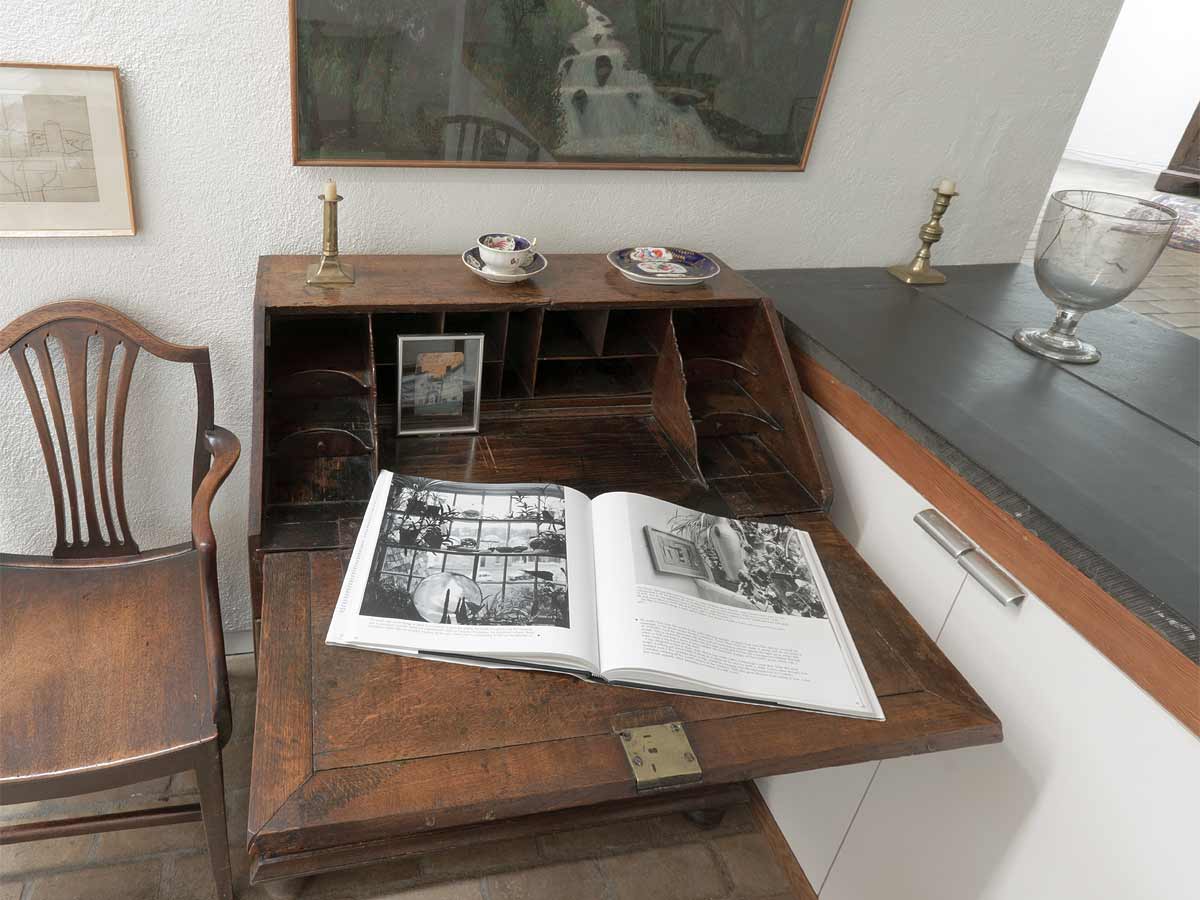

In 1956, Jim Ede bought four cottages here and transformed them into an open house ‘in which stray objects, stones, glass, pictures, sculpture, in light and in space, have been used to make manifest the underlying stability.’ Prior to moving to Cambridge he was a curator at the Tate Gallery in London.

Kettle’s Yard House has been kept pretty much as it was when he was here, with his remarkable collection of paintings by Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Alfred Wallis, Christopher Wood, David Jones and sculptures by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

It’s a fantastic place, full of harmonious arrangements and enthusiastic attendants keen to share their love of this treasure house. There’s always something new to discover here. I’d not noticed this tiny Ben Nicholson relief before, perched on a windowsill. But this scrubbed circular table with its spiral of pebbles and little bronze sculpture by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska is where I always stop and stare.

Happily here I can take as many photos as I like. And everything is photogenic. Wherever I point my camera I often find something delightful I’ve not seen before. But conversely, old favourites might sometimes disappear, temporarily withdrawn to give others a chance.

This upstairs bedroom, with its display case of paintings by Ben Nicholson and constructions by Naum Gabo, is usually the place to find Winifred Nicholson’s Daffodils and Hyacinths in a Norman Window but it wasn’t here on this visit, replaced by a display of paintings by Vicken Parsons.

Flora in Calix Light by David Jones is another favourite, a wonderful inside outside painting. I like to pay my respects every time I visit, it’s a touchstone, but this time it was also missing, replaced by another Vicken Parsons painting. I learned it had been removed to Discoveries at Two Temple Place in London, an exhibition of objects from eight Cambridge museums.

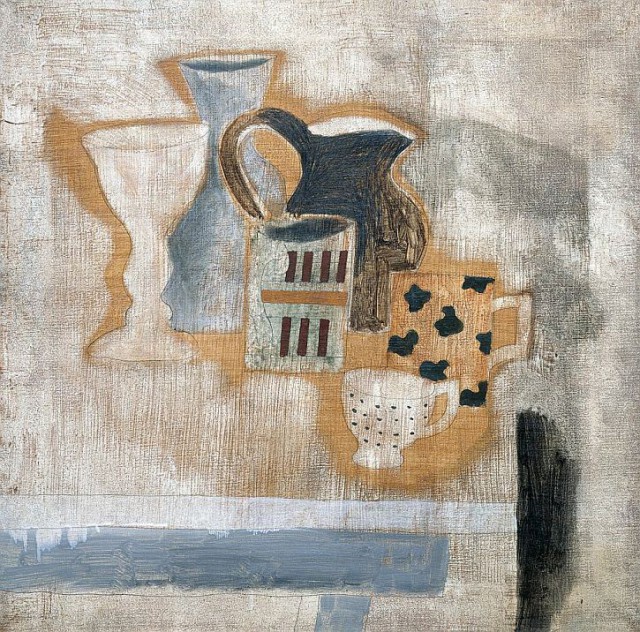

Another place to linger is always this window of dappled light, on the bridge between the older cottage building and the newer extension. Today it seems unchanged, still home to Ben Nicholson’s painting, 1944 (three mugs), in its quirky frame hung on a less than vertical wall.

I kept a postcard of this painting pinned to the wall of my workshop for many years. It inspired my own little homage, Still Life with Ben Nicholson Postcard, 1989.

I think my first introduction to Ben Nicholson could have been this handy little book, found in an anonymous second-hand bookshop somewhere back in the 1970s, looking for the ‘primitive impulse’.

It is extremely difficult to find in the visual arts today something as unselfconscious, as genuine, as direct and vital as we find in the most primitive art. A young and handsome black and white cat used to visit us almost every day in St Ives, usually looking down from our terrace through a window into the kitchen while we were eating, and asking to be let in. When we opened the door he would saunter in as if he owned the place, wander round, give our ginger cat a friendly push and brush past us with his whiskers as we sat at table to a particular highly polished spot in the middle of the floor and there he would perform a couple of extremely off-hand trial pirouettes followed by a single perfected pirouette, the circle of which was completed by his looking exactly under the kitchen dresser for an imaginary mouse. He made this pirouette on several occasions on this spot but I never saw him make it in any other place in the house and it is this kind of reaction to a set of circumstances which will have produced the first creative sculpture and painting.

A primitive painter only a little less primitive than the black and white cat will have worked on any form in which he was interested in order to try to realize in this some ‘experience’, something not on the surface but as deeply embedded in the material as in himself. This instinctive and unspoilt approach has a natural conviction and is capable of producing something even more actual than the original experience.

If a painting is worked out within the terms of its medium then its edge, the outside edge of the form on which it is painted or worked, has a vital importance. The artificial conditions produced by painting on a stretched, rectangular canvas, later to be framed and sent to an exhibition, have forced painting out of its true direction and out of its natural and direct relationship to our lives, and it is difficult to understand why so many painters accept this convention without question: the entire form of a painting must be considered just as the entire form of a sculpture has to be considered; and it is this consciousness of the form , of the ‘total form’, in classical painting which makes possible its extension into the other arts and into our lives.

Ben Nicholson 1962.

I’ve been trying to remember my first visit to Kettle’s Yard. I think I discovered it at the end of the 1970s after I moved to London. I used to cycle up to Cambridge on pilgrimage to Kettle’s Yard. It’s mixed up with the memory of a film by Ken Russell called Savage Messiah after Jim Ede’s book about Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. But mostly I came looking for Ben Nicholson, though I found much more. I remember one occasion turning up to find it closed; I tugged on the bell-pull at the door to the house and it was opened by the curator, Mike Tooby. I handed him a set of slides of my paintings and suggested he might like to exhibit them. In retrospect I’m grateful he didn’t laugh, I was good at making a fool of myself in those days. But Sandy Nairn, brother of the present director of Kettle’s Yard, gave a group of us an exhibition at the ICA and when it later travelled to St Andrews, Mike Tooby very kindly wrote the catalogue essay. So, maybe a kind of Kettle’s Yard exhibition by proxy!

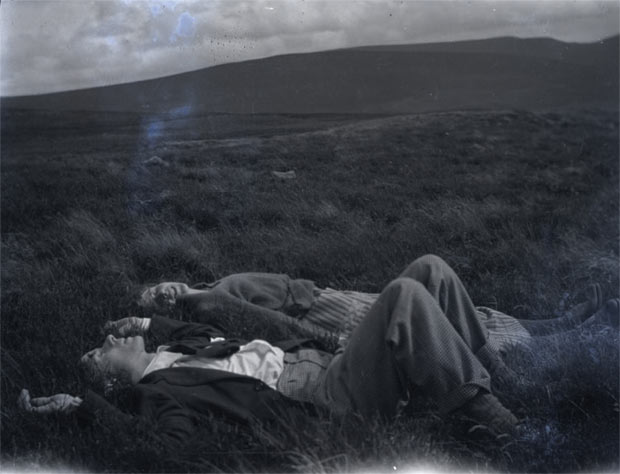

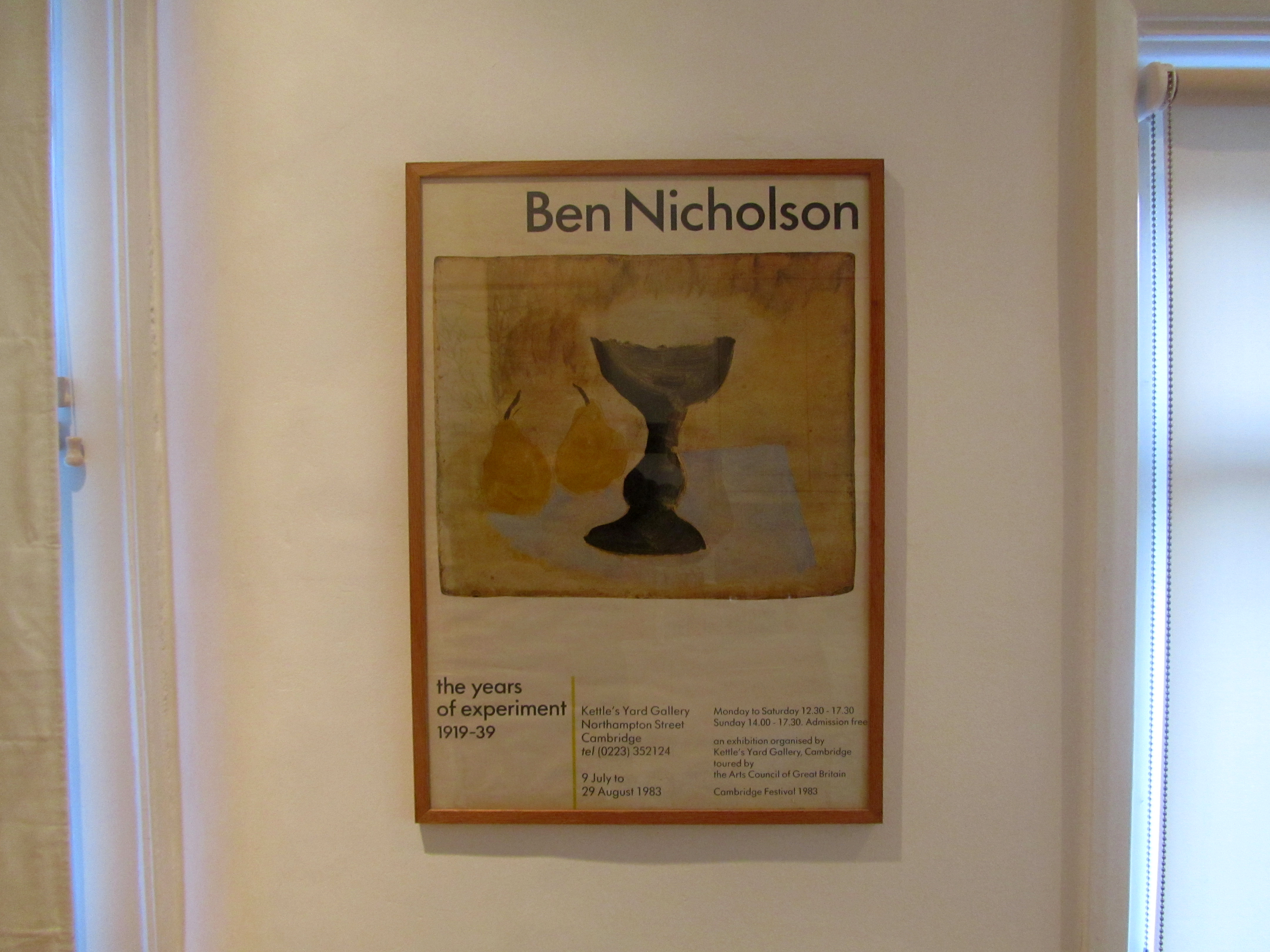

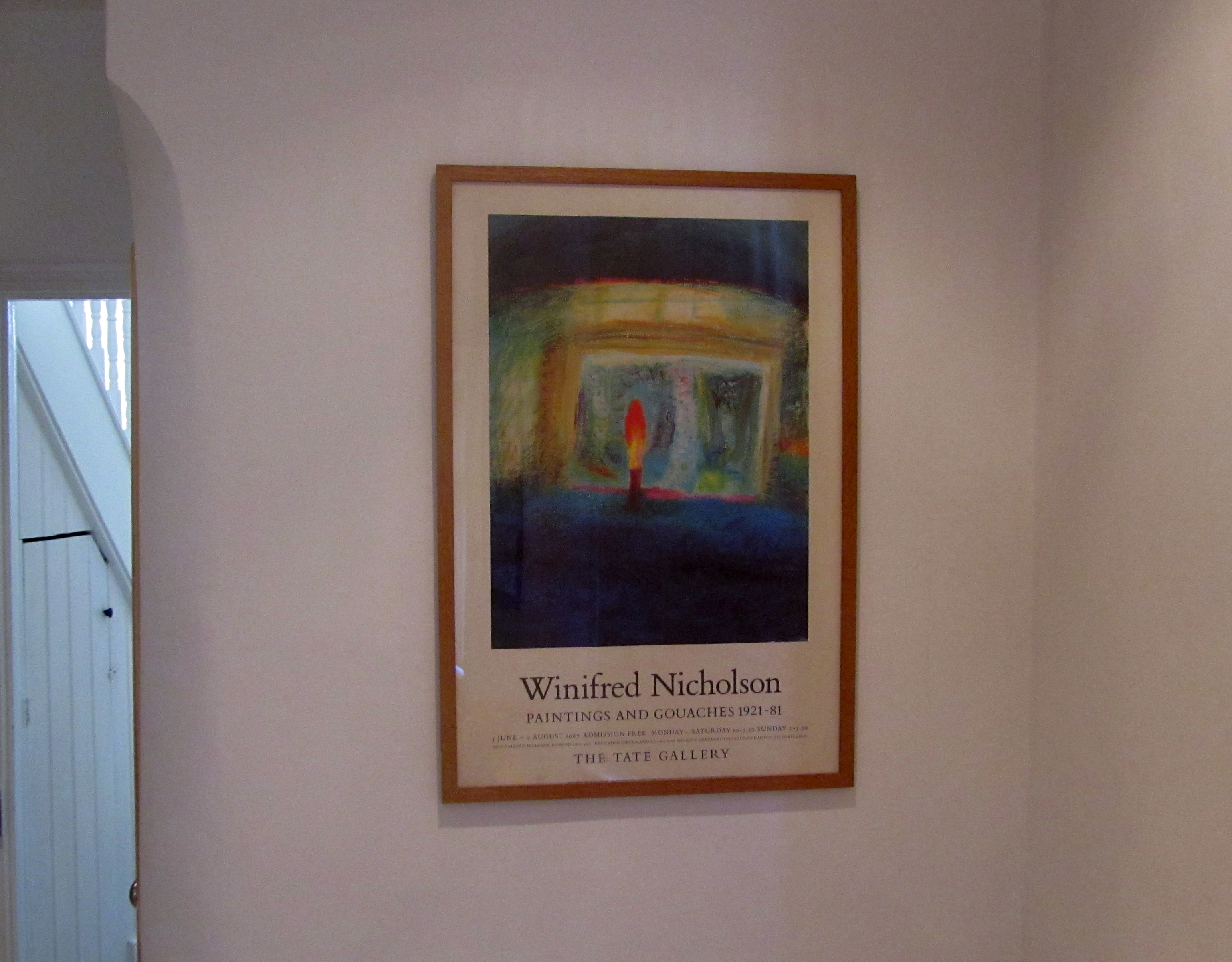

Two posters at home from the 1980s, souvenirs of two memorable exhibitions. Art & Life promised to be a revisitation. On the bench outside the entrance to the gallery we found ghosts of an earlier visit.

In 1970 Kettle’s Yard house was extended and a small gallery was added, opened by Prince Charles with a performance by Daniel Barenboim and Jacqueline du Pré. In 1981 the gallery was extended, then again in 1986 and a further extension opened in 1994. Work continues on plans to develop Kettle’s Yard still further; view the architect’s proposed drawings here.

※

Ben Nicholson was born on 10 April (a good day for a birthday), 1894 in Denham, Buckinghamshire to the painters William Nicholson and Mabel Pryde. He enrolled at the Slade School of Art in 1910 but left after only one year. Winifred Roberts was born on 21 December, 1893 in Oxford to Charles Roberts MP and Lady Cecilia Howard. In 1912 she enrolled at Byam Shaw School of Art, which was then located on Campden Street in Kensington, just up the road from The Rowley Gallery. When I first started working there we would often leave redundant frames out in the street for Byam Shaw students. I like to imagine that in earlier days Winifred might have taken one. Ben and Winifred met in the summer of 1920 and married later the same year. They honeymooned in Castagnola by Lake Lugano on the Swiss Italian border, where they returned each winter for the next three years.

These three paintings which begin Art & Life were produced during their time together at Lugano. Photography was not permitted in the gallery; exhibition images are courtesy of Kettle’s Yard.

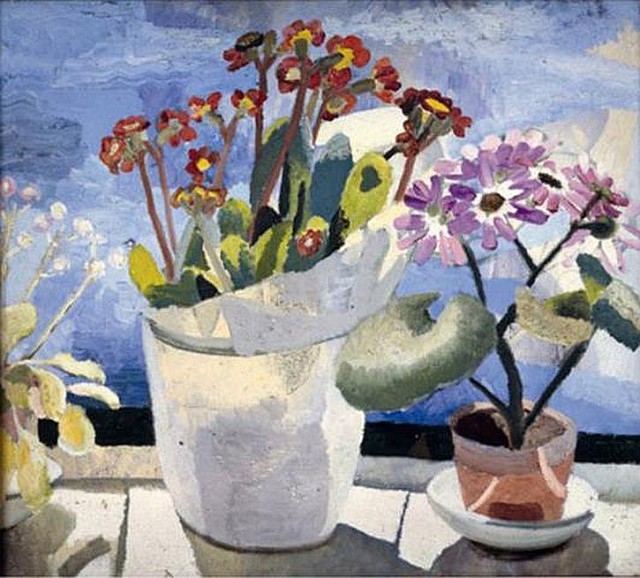

Winifred Nicholson, Cyclamen and Primula, c.1922-23, Oil on board, Kettle’s Yard.

[Cyclamen and Primula] has not only the local life of these particular objects, flower, pot, plant, paper; it has the sense of air and space, of birds in the air, of sounds and warmth, of domestic life in its essential simplicity; and of the joy of opening windows; not only material ones, into a bright morning. Much more beside; the poetry of life, but seasoned with a strong robust element of common sense, the touch of reality; that actual world which is so necessary to such an artist as Winifred Nicholson in order to call out her power and response; a response which is to produce a work of her own in the likeness of the world that touches her.

Jim Ede 1984.

※

Ben Nicholson, 1921-c.1923 (Cortivallo, Lugano), Oil on canvas, Tate.

This mounting sense of freedom and excitement, and his realisation of the importance of intuition and spontaneity, must have been greatly helped by Winifred Nicholson’s own work and by her originality during their joint voyage of exploration. Painting in Castagnola with her, he began to see how pictures could be turned into physical events by treating them physically, by incising and scraping, by letting a pencil line escape across a board in pursuit of the nervous system of walls on a viridian fellside, by wiping clear a patch in a field in which to stand a farm animal, or by drawing the simple solid geometry of white farm buildings. Often he spoke of the artist’s freedom to base decisions on nothing more complicated than the pleasure to be derived from taking them: the way in which a picture is an exhilarating experience to make can also communicate itself to the viewer as an experience, not just as an object.

Christopher Neve 1993

※

Winifred Nicholson, Polyanthus and Cineraria, 1921, Oil on canvas, Private Collection.

[Winifred Nicholson’s] flowers which seem so flower-like, and I know of no one who approaches so closely to the pure clarity of flowers themselves, are profoudly characteristic of the strength of mind and character which has received and responded to the flower life; making from this life a life of its own, a massive simplicity which is yet so delicate, so poised, so true…

Winifred Nicholson is a colourist. Colour has always been her chief interest. She wrote, ‘as a child I painted rainbows… sunlight coming through chestnut leaves, setting a leaf aglow… things up against windows so that the sunlight could be seen coming through them, all luminous; contrasted with the sunlight striking on them, all shine. I never painted in a room that did not face the sun, nor when the sun was not shining’.

Jim Ede 1984

We have cobalt green with our coffee for breakfast, lunch at 4, and rose madder for supper, and all our clothes smell of turpentine.

Winifred Nicholson 1922

※

Ben Nicholson, 1923 (Dymchurch), Oil on canvas on board, Private Collection.

On the opposite wall there’s a painting that I’d not seen before. It was made after Ben and Winifred visited Paul and Margaret Nash at Dymchurch on the Kent coast. Its flat bands of colour emphasise the painting as an object, and particularly as seen in the exhibition where it was enclosed by a wide grey-green roughly painted frame.

※

Ben Nicholson, 1924 (first abstract painting, Chelsea), Oil on canvas, Tate.

This painting is the result of a collage, the shapes evoke torn paper. It’s a taste of things to come, his abstract table-top compositions and even a suggestion of The Snail by Henri Matisse 30 years later.

※

Ben Nicholson, 1925 (still life with jug, mugs, cup and goblet), Oil and pencil on canvas, Private Collection.

But of course I owe a lot to my father – especially to his poetic idea and to his still life theme. That didn’t come from Cubism, as some people think, but from my father – not only from what he did as a painter but from the very beautiful striped jugs and mugs and goblets, and octagonal and hexagonal glass objects which he collected. Having those things throughout the house was an unforgettable early experience for me.

Ben Nicholson 1963

※

Winifred Nicholson, Dressing Table, Sutton Veny, c.1925, Oil on canvas, Private Collection.

It was painted while staying with Ben’s father, William Nicholson, at Sutton Veny in Wiltshire.

Fresh clear sunlight and silvery shadows of rain, white violets and smell of green buds in the outside world and… a queer almost unbelievable harmony. We all get on so well together. There seems a kind of unspoken understanding that seems magic, like things look reflected in water. Each morning I wake up expecting it to be broken and vanished, but there it is persistent, frail, unseen, yet with a kind of glowing light…

Winifred Nicholson 1925

※

In 1923 Ben and Winifred bought Banks Head, a farmhouse on Hadrian’s Wall in Cumberland, where Paul and Margaret Nash, Ivon Hitchins and Christopher Wood came to visit them. They explored the surrounding landscape and sometimes they painted together. Christopher Wood said – ‘Banks Head is the painter’s life’ and ‘I am on the verge of the real thing after what I learned at Banks Head’.

Winifred Nicholson, Northrigg Hill, c.1926, Oil on canvas, Private Collection.

The earth of Cumberland is my earth, way back to the Medieval, to the Roman times, the Celtic bronze-age time. I have always lived in Cumberland – the call of the curlew is my call, the tremble of the harebell is my tremble in life, the blue mist of lonely fells is my mystery, and the silver gleam when the sun does come out is my pathway.

Winifred Nicholson

※

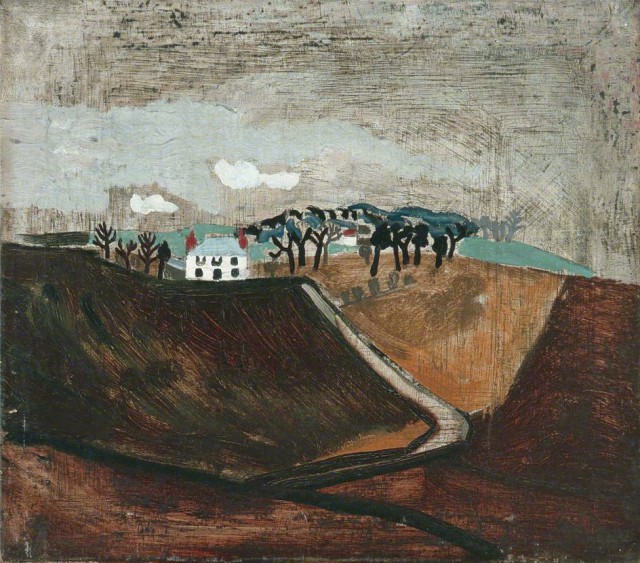

Christopher Wood, Cumberland Landscape (Northrigg Hill), 1928, Oil on board, Kettle’s Yard.

The interaction of these three spirited artists was complex and is not easily analysed, owing partly to the insecure dating of many of their works… Kit Wood brought up-to-date information about art in Paris and its many styles and methods. During the earlier years of their friendship, his landscapes were more traditionally descriptive and thinly painted, and rooted in tonal relationships rather than relationships of colour. After 1928 they tend to be less detailed and more inventive in the selection and simplification processes they depended on. Here Ben Nicholson’s influence was important – Wood used to say to Winifred about his own latest work that Ben Nicholson would probably tell him he should have left more out.

Norbert Lynton 1993

※

Ben Nicholson, 1930 (Cumberland farm), Oil on canvas, Brighton & Hove Museums.

[The Nicholsons’] direct and simple approach, the nearest Wood ever came to realising in paint his long-stated intention to see with the eyes of a child, was reinforced by a simple and unfussed approach to preparing the canvas. He encouraged Ben and Winifred to use a technique he had devised of coating the surface with a thick white paint called coverine. It dried fast and could be put on over old work, a useful recycling technique for once- twice- or thrice-used canvases and, as the layers built up, it gave the new surface a rich and varied texture, giving… a sense of history to the work.

Richard Ingleby 1995

※

Ben Nicholson, 1928 (Walton Wood Cottage no.1), Oil on canvas, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

For Ben sophisticated naivety was the necessary first step in slowly building up a personal language which would eventually go beyond the faux-naïf and, by an ever greater refinement of complexity, regain the ‘simple’. In Walton Wood Cottage no.1, which he painted in spring 1928, the swift execution is one facet of his deliberate primitivism.

Peter Khoroche 2002

※

Christopher Wood, Still Life in a Bankshead Window, 1928, Oil on canvas, Fine Art Society.

Painted after receiving a black & white photograph sent by Winifred of Ben’s painting, Walton Wood Cottage no.1.

The resulting painting ‘Still Life, Bankshead’, lifts the wood and cottage almost directly from Ben Nicholson’s picture and replaces his large foreground tree with the blue glass full of flowers. The colour is much sharper than his usual palette, a sign perhaps that he was trying to force the Bankshead jollity. One curiosity concerning Wood’s picture is the way that the trees seem to be floating among clouds or some sort of fog. This was presumably his reading of Ben’s black-and-white photograph from which he got slightly the wrong impressions of the early morning mist. The Nicholson original has no sky. In Wood’s picture the sky seems to be taking over.

The flowers, and to some extent the colour, came from Winifred. The landscape from Ben. It is a picture which, appropriately, either he, or his mother after his death, gave to Winifred. I have mentioned his insistence on the completeness of their relationship and in this picture he has very deliberately painted them both in and, of course, he is there himself. It is a picture with all the right ingredients, but it falls short of being one of his best. The combination does not quite work. In some ways it is an appropriate metaphor for their three lives. ‘Bankshead satisfied me’, he said in another letter, ‘…because it was complete’, but he continued, ‘complete without me, therefore is not mine’.

Richard Ingleby 1995

※

Ben Nicholson, 1929 (Holmhead, Cumberland), Oil on canvas, Private Collection.

From 1928-30 Nicholson painted a series of ‘naïve’ landscapes and seascapes… which are suggestive of directness, expressiveness and innocence, while at the same time showing considerable thoughtful reworking. The trees in a painting such as ‘1929 (Holmhead, Cumberland)’ recall the work of Van Gogh in their anthropomorphic nature (a characteristic also of Wood’s paintings at this time), whereas the depiction of the horse can be associated with the art of children. The weathered texture is typical of Nicholson’s paintings in this period.

Jeremy Lewison 1991

※

Winifred Nicholson, Summer, 1928, Oil on board, Leamington Spa Art Gallery and Museum.

In the summer of 1928 the Nicholsons holidayed at Pill Creek, Feock in Cornwall. According to Winifred – ‘It was a sleeping beauty’s countryside of southern foliage, sheltered creeks and wide expanse of placid water’. They were joined by Christopher Wood – ‘This is a beautiful place, a little creek with pine woods and white yachts at the end of the large inlet with Falmouth at the head’.

※

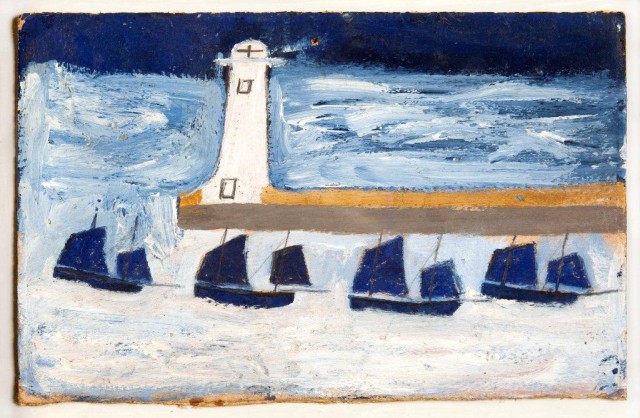

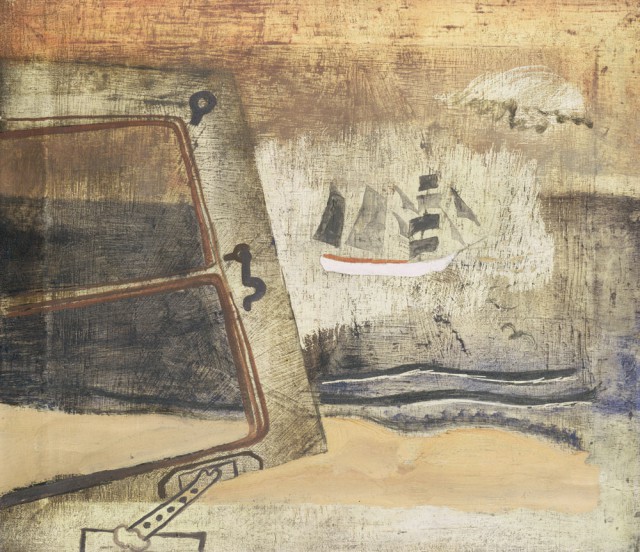

While staying at Feock, Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood made a day trip to St Ives where they met the self taught marine painter Alfred Wallis.

Alfred Wallis, Four Luggers and a Lighthouse, c.1928, Oil on card, Private Collection.

What I do mosley is what use To Bee out of my own memery what we may never see again as Thing are altered all To gether Ther is nothing what Ever do not look like what it was sence I Can Rember.

Alfred Wallis 1935

※

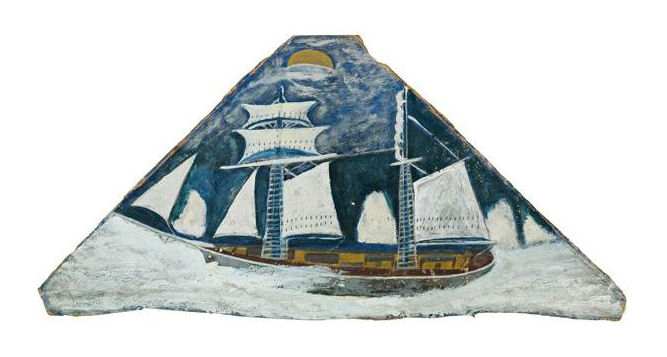

Alfred Wallis, Schooner and Icebergs, c.1928, Oil on card, Private Collection.

He paints all day – imaginative, elemental strange pictures on scraps of cardboard or old boxes. His simple ferocity makes most painting look utterly insipid.

Winifred Nicholson 1928

[Wallis] enjoyed talking about his paintings, speaking of them not as paintings but as events and experiences.

Ben Nicholson 1943

In seventy years’ contact with the sea awake at any time – day or night, in darkness or light, storm or calm, a great deal of experience must have accumulated, and it is out of this store that this old man produced his paintings. When he painted the sea and a ship he knew that the ship is feather-light as compared to the vast weight of the sea. How was he to express this in terms of paint, this very obvious fact so little realised by other painters? It is not easy to express and I wrote of it at length – but I don’t suppose that Wallis gave it a conscious thought, for when he painted, his awareness being so sure, it comes out right. He knew what it was to be at sea – entirely and totally – his paintings carry with them a ship-feeling, and a land-in-the-distance feeling and a pitching and tossing and a passing of lighthouses and other ships and a blinding of spray, and a vastness of sky which somehow seems above and below.

Jim Ede 1984

※

Ben Nicholson, 1928 (Porthmeor Beach no.2), Oil on canvas, Private Collection.

Clearly Wallis appealed to Nicholson’s romantic (and modern) valuation of the primitive and childlike. But more specifically he was excited by Wallis’s ability to make his pictures come alive, partly by the sheer intensity of his feeling, partly by his method of working, which allowed the material make-up of the painting to be undisguised yet, through the viewer’s eye, to be transformed into a vivid experience. This confirmed Nicholson in his tendency to stress in his own paintings the process of their making, so that they should be artefacts to be appreciated for themselves as much for whatever they might refer to outside themselves.

Peter Khoroche 2002

※

Winifred Nicholson, Seascape with Two Boats, c.1932, Oil on canvas, Kettle’s Yard.

… A swirl of grey brushstrokes marks the progress of the sailing boat at the centre of the painting; the background landscape of khaki green shimmers in a welter of rapid brushstrokes. The colouration here remains very much Winifred’s own; there is no sense of Wallis’s ‘peculiar, pungent Cornish greens’ or his angular, dizzying perspective. Winifred’s depiction of one of her children playing with the toy yacht that Wallis had made for them is a very personal way of acknowledging the old painter’s importance as one element held in tension against others in a continually developing motion.

Jon Blackwood 2001

how is The little as he sailed is Boat yet i serpose you have a pool with you near By try it i do not think it ever Been tried if he is like me i was always for Boats you must go out and Try it

Alfred Wallis 1929

※

Christopher Wood, Le Phare, 1929, Oil on board, Kettle’s Yard.

This work was made on Wood’s first visit to Brittany. Its title emphasises the French context, yet its content and method is the most powerful example of Wood’s affinity with Alfred Wallis. The tilt of the boat as it turns in the flat wall of colour that denotes the sea is almost a pastiche of the work of the old St Ives fisherman artist. Even the support, a piece of old board, adds to the sense of the work as an act of homage. The newspaper that gives the work its title, ‘Le Phare’ (The Lighthouse), is a deliberate recollection of the image of the lighthouse that figured in so many of Wallis’s compositions, as well as in Wood’s own work of the previous year. Wood sets this reference to a guiding light alongside the playing cards, used in other works of this time. Painted in France, this work clearly shows that Brittany evoked strong memories of Cornwall for Wood.

Michael Tooby 1997

※

Art & Life is interspersed with stoneware pots by William Staite Murray, who often showed his work alongside Ben and Winifred Nicholson. He believed pottery offered the potential to combine the abstract possibilities of both painting and sculpture.

William Staite Murray, Roundabout, 1926, Stoneware vase, York Art Gallery.

The clay spirals upward in the hands of the potter, this spiral formation allows the clay to expand and unfold, for a pot grows from within, much as the whorled rose unfolds her petals, and all forms of organic life unfold their spiral construction in growing. The potter’s wheel establishes the fact that spinning Earth is a vast potter’s wheel, moulding organic forms out of earth and water.

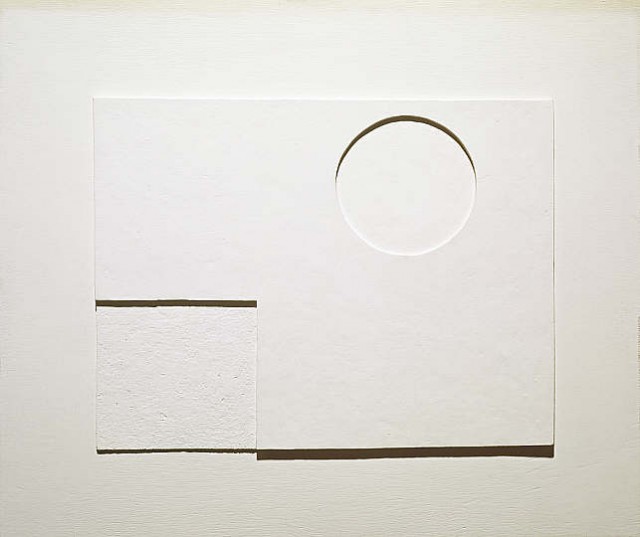

The exhibition ends with a trio of abstract paintings, Winifred’s in the middle, Ben’s on either side and the revelation that she gave him the circle idea, which he took as the seed for the development of his later, more familiar, abstract paintings and reliefs. In a letter to Winifred, Ben wrote:

I do connect the ‘circle’ idea as coming a great deal from your constructive thought and all the new ideas you have found since then.

Ben Nicholson, 1935 (white relief), Oil on carved board, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

※

Art & Life seems naturally suited to Kettle’s Yard, the perfect exhibition seen as an extension to the permanent collection on display in the house. But it’s actually a touring show. It was first seen at Leeds Art Gallery and after Cambridge it will travel to Dulwich Picture Gallery. Maybe I’ll see it again there.

In his book, A Way of Life, Jim Ede recalled:

The forming of Kettle’s Yard began, I suppose, by my meeting with Ben and Winifred Nicholson in 1924 or thereabouts, when I was an assistant at the Tate Gallery… It wasn’t until I was nearly thirty that the Nicholsons opened a door into contemporary art and I rushed headlong into the arms of Picasso, Brancusi and Braque…

… in a world rocked by greed, misunderstanding and fear, with the imminence of collapse into unbelievable horrors, it is still possible and justifiable to find important the exact placing of

two pebbles.

The Venetian mirror… When I first hung it in our bedroom we could not sleep all night, it was like having the moon for company, so bright it shone.

And then there’s another, much smaller book in the shop as we leave, A Room to Live In, a delightful compilation of writings in celebration of Kettle’s Yard.

… successive visits bring recognition and growing familiarity but also, always, objects and juxtapositions noticed properly for the first time. It is a bit like walking into that nexus of the moment and timelessness embodied in Eliot’s ‘Four Quartets’. – Lawrence Sail

I ring the bell of the house, sign in and go straight upstairs. The house is full, as usual, of happy-looking visitors. You can tell the new from the old. The new ones wander about in a wide-eyed exclamatory ecstasy of disbelief. The ones who’re returning either wander through the house with the kind of pride that means they think it belongs to them, or, if they’re with someone, make straight for their favourite places and artefacts, saying things like Come and see! or Wait till you see it! – Ali Smith

From this distance, you can only speculate how this mannerly English gentleman [Jim Ede] would have reacted to the plentiful crowds who presently flow through Kettle’s Yard, and who now treat its existence as an artistic given. It’s become a rare example of something which is no less beautiful for being bigger. But in those days, there were certainly long afternoons when I was alone, or in the company of only one or two friends. It wasn’t any particular work of art or artefact which drew me… it was the feeling, completely new to me, that modernity could be calming, and that the place where you lived could embody the idea of who you were as a person. – David Hare

※

Outside, recycled and recharged with life-affirming art, it’s time to find refreshment back in town. The Eagle is a good source of life-giving DNA. It was here that Francis Crick and James Watson announced they’d ‘discovered the secret of life’ in 1953, at the nearby Cavendish Laboratory. Today, the pub commemorates their discovery by serving a special ale known as ‘Eagle’s DNA’.

We returned along the river, our way marked by willows and poplars, punters and anglers, handy with poles and wary of splinters, sprinters in kayaks and territorial swans – and a river of green is sliding unseen beneath the trees, laughing as it passes through the endless summer making for the sea.

Pink Floyd – Grantchester Meadows

Television Personalities – I Know Where Syd Barrett Lives

Art & Life / Kettle’s Yard / Grantchester

※

PS: Next day, in the Guardian: England’s hottest day of the year so far, with temperatures reaching 20C, drew many to the river Cam while runners sweated nearby in the Cambridge half-marathon. Eyewitness: Cambridge, UK.

Thank you for this wonderful post. Whenever I feel I need my batteries charging, I take out my copy of ‘A Way of Life’

I LOVE Kettles Yard. In fact I wish I lived there!

A Way of Life looks like a great book. You’re fortunate to have a copy. It would make a perfect birthday present. Maybe one of these days!

Wonderful combination of art and place. Kettle’s Yard has been one of my haunts since I went on a art department trip from Goldsmiths’ College in the late 70s. I had read Savage Messiah too. The house has such a serene atmosphere, life as art. I am going to the exhibition shortly I hope so thanks for the preview! There is also one on John Craxton at the Fitzwilliam until 21st April.

Thanks Diana. I hope you get to see the exhibition at Kettle’s Yard. It makes perfect sense there. I would’ve liked to have seen the John Craxton exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum too but we ran out of time.

What a wonderful post. The music was a nice touch.

By the way, 21 December is also a good day for a birthday.

Cheers Bill, thanks for looking. 21 December is also my brother’s birthday.

Oh this is wonderful thanks. I went to Kettles Yard some years ago and was amazed at how beautiful it was. I haven’t been around very much but now I realise what I’ve been missing! Great pictures as always. Hope you’re well and enjoying the spring. Sarah