I was in a room with many people. They were mostly grey haired and quietly dressed in the way of National Trust members. One or two young men stood intently looking. The room titled We Are Making A New World is the gallery in the Tate exhibition devoted to Paul Nash’s WW1 paintings. It is quiet except for the gentle tap of feet or the occasional mute whisper. The mood is that of a chapel of remembrance. As though the only person with a right to speak was Nash. The silence of these works is awe inspiring considering the ear shattering noise that would have dominated the scene, as well as the stink of shit, rotting flesh, tobacco smoke and cordite. We are silenced by the works hung on these walls. The older visitors seem to be wrapped in memories passed to them by fathers and grandfathers who had seen this for themselves. The young men I take to be artists come to understand how this great artist had made these images, witness to such pointless violence.

I have been worrying about how to make new work interpreting landscape. It might be that Paul Nash and his relationship with the land holds clues to how I might proceed. For the past 30 years or so I have been visiting a location that was an inspiration for Nash through much of his life. Wittenham Clumps, a pair of small hills in the Thames Valley just south of my home in Oxford.

They rise from the plain of the Vale of the White Horse at the most a few hundred feet. Conjoined hillocks. Now in the stewardship of The Earth Trust; but a centre of human activity from pre-Roman times. Each is topped by a grove of trees, the lower of the two enclosed by an earth ditch and embankment engineered in the iron age. They sit over the river from Dorchester on Thames, a town with origins in Roman Britain whose abbey contains a wonderful tomb figure of a knight, much admired by 20th century modernist artists, Henry Moore and John Piper.

I have painted here often, en plein air, but found one is almost always looking outward. The image of the clumps comes from an accumulation of experiences that add up to a composite image that one sees only in the mind’s eye. The Nash paintings from the end of his life, Landscape of the Vernal Equinox and others are based on a view he had from Boar’s Hill. I went there and one hardly notices the hills they are so far off. Nash looked at them through binoculars which had the effect of flattening the perspective and reducing the distance.

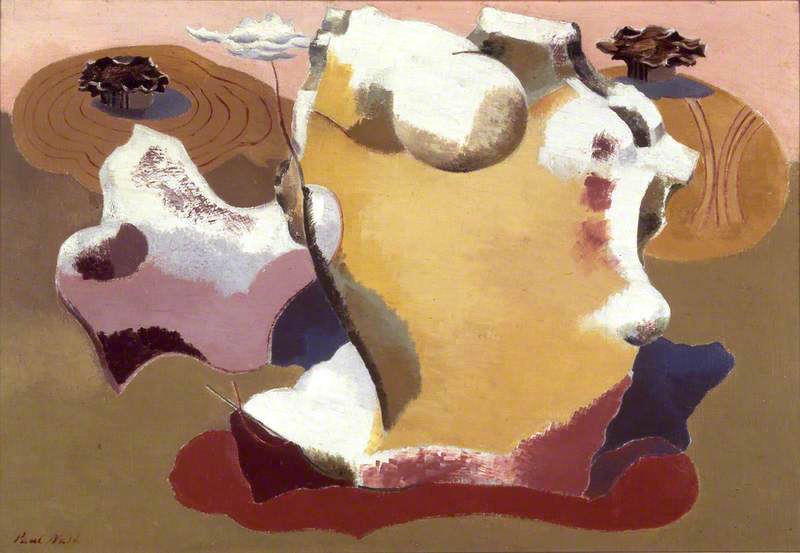

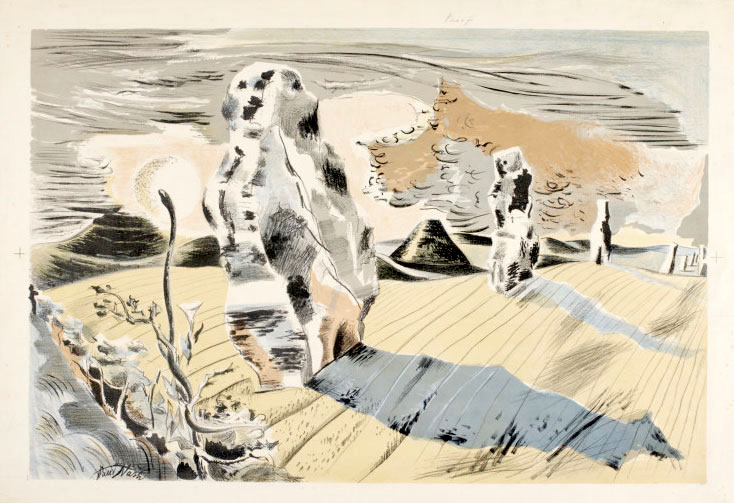

When visiting the Tate’s Nash exhibition I was struck by the obvious fact that he painted his landscapes in the studio. I guess he may have made some small working notes in pencil or watercolour out in the landscape but his work is of what the poet Kathleen Raine called “the landscape of the mind”. Never a topographical artist, his work was an exploration of the complex relationship accumulated through his own experience, walking, looking, remembering, combined with knowledge of archaeology, myth and poetry. His writings are extensive, demonstrating a hugely ranging intelligence.

I recently spent a day with my son, high above the Sussex coast on the South Downs at Chanctonbury Ring. We had gone there as a test to see what might happen if we worked in the same place. He is a maker of TV documentaries and a photographer.

On the way home, trudging along an icy track crunching frozen puddles and frosted flints, we discussed what might come next. It occurred to me that Britain, with its long history of landscape art is missing something; it has a National Portrait Gallery, a National Maritime Museum, The Imperial War Museum, the V&A etc but no National Landscape Gallery. Is it so obvious that it has never occurred to anyone that this is a strange anomaly? Tate Britain has the Clore Gallery devoted to J.M.W.Turner but there is no gallery solely devoted to our engagement with the land. Maybe we need a campaign to initiate one.

Paul Nash, while almost exclusively concentrating on working from his home environment, made images of universal significance. I have painted at various times in India, Spain and Canada. Last autumn I drove over the Rockies from Alberta across British Columbia to the west coast. A thousand miles of zig zagging route. When possible I stopped and made drawings or watercolours. Quick notes to prod my memory when I got home. On previous visits I found that the colour palette that is natural to me is one tuned to the soft humid climate of England. The scale, distance, light, fauna etc of BC needs a distinct palette. This time I just worked in Payne’s grey as I knew there was not enough time to adjust my retina to see the spectrum of western Canada. It might be that I am unable to, however long I spend there. There are blues so vibrant and deep that no paint can capture the luminosity. Strange milky emeralds in rivers and lakes, the colour formed from glacial meltwater.

So many contradictions. We experience the world in many environments, many cultures, at different speeds. We fly, drive, cycle, walk. To sit and quietly look is difficult with all the chatter in the world. Politics or family concerns are ear-worms nagging away to distract from where we are. One aspect of painting for me is the slowing down needed to be open to what is there before my eyes and what I hear and smell. I guess it is a kind of meditation. From this I have made a few paintings that seem to work. But here is Nash pointing outward to many other pathways. His work seems to predict Richard Long and James Turrell, and many of the experimental artists of the present. After all, while he is thought of as a painter, he also wrote eloquently and was an interesting photographer. His fascination with the megaliths of Avebury, his illustrations of the C17th writings of Thomas Browne, are lessons that I hope to learn from.

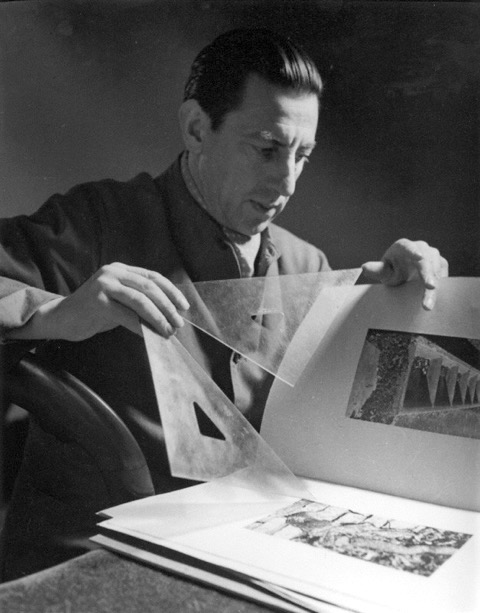

My feeling of connection with Nash is also that, though he died the year before my birth, he lived in Oxford for his last six years in a house not half a mile from my home. I can cycle to Boar’s Hill and Wittenham Clumps from my present home. My mother’s great friend, Helen Muspratt, a great photographer, had taken his portrait. If only I had known when I was younger I could have asked her about him but I was ignorant of her reputation as a photographer, thinking of her as someone who was yet another left wing CND activist who frequented our house.

And so standing in front of the wonderful painting of beech trees, Wood On The Downs, from Aberdeen Art Gallery I am transported out onto the hills of the South Downs, the wind shaking the winter branches that my son is photographing. A woman circles the ditch and embankment of Chanctonbury Ring in some form of private rite. We brew tea with a small fire of twigs and leaves. The wind cuts through clothing as it arrives from somewhere chilled on the continent and the sun arcs across the English Channel.

Paul Nash at Tate Britain / Wittenham Clumps

Andrew Walton / The Rowley Gallery

I grew up on a farm that looked on to Wittenham Clumps. I went to art college and became obsessed with Nash and his take on the Clumps so much so that in 1992 I revisited the hills and drew the results can be seen here. I never split up the sequence of drawings as I rightly suspected I would not get another chance to document them in this way. I have never shown them which a shame.

The images can be seen here:

http://www.shaunbelcher.com/painting/?p=843

http://www.shaunbelcher.com/painting/?p=778

Hope you may find of interest and thank you for the blog post above.