Last August, on holiday in Sicily, a short walk out of Ortigia through the hot dusty streets of Syracuse brought us to Neapolis, one of the largest archaeological sites in the Mediterranean. The entrance is beside the little Norman church of San Nicolò dei Cordari, which was built over part of an aisled Roman piscina, a reservoir to provide water for the nearby amphitheatre.

The Altar of Hieron II… built between 241 and 217 BC, was used for public sacrifices to Zeus, when as many as 450 bulls could be killed in one day. It was 198m long and 22.8m wide (the largest altar known) and was destroyed by the Spanish in 1526 in order to use the stone for harbour fortifications. The altar was presumably about 15m high and elaborately decorated; the sacred area in front of it contained a rectangular pool for ablutions and was delimited by a colonnade, more or less where the cypress trees stand today.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

As we approached the Greek Theatre we came under the medieval watchtower overlooking the site.

On the right-hand side of the road, opposite the altar, is a gate which leads to the Greek Theatre, the most celebrated of all the ruins of Syracuse and the largest Greek theatre in Sicily (138m in diameter). Archaeological evidence confirms the existence on this spot of a wooden theatre as early as the 6th century BC, and here it was that Epicharmos (c. 540-450BC) worked as a comic poet. In c. 478 BC Gelon excavated a small stone theatre, engaging the architect Damokopos of Athens. It was inaugurated by Aeschylus in 476 BC with the first production of ‘Women of Aetna’; his ‘Persian Women’ was performed shortly afterwards. The theatre was enlarged in the 4th century BC, under Timoleon, by excavating deeper into the hillside; it was again enlarged under Hieron II (c.230BC), by extending the cavea upwards, using blocks of stone. It could thus hold an audience of 15,000; some scholars think even more.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

An ancient solar dish, brimful with the scorching heat of the midday sun.

It was not a place to linger too long.

We found some shade under the rock wall above the theatre where there is a nymphaeum, a grotto fed by the Galermi aqueduct bringing water from the River Bottigliera near Pantalica, 33 kilometres away.

And lots of burial chambers, with recesses alongside for votive pinakes, painted memorial tablets.

At the left-hand end of the wall the Via dei Sepolcri (Street of Tombs) begins, rising in a curve 146m long. The wheel-ruts in the limestone were made in the 16th century by carts serving the mills which at that time occupied the cavea of the theatre. The Byzantine tombs and Hellenistic niches in its rock walls were all rifled long ago. Its upper end crosses the rock-hewn Acquedotto Galermi.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

From the edge of the wall we were able to see down into the Latomia, a spectacular deep quarry, now overgrown and transformed into a lush garden. It looked like an inviting, shady idyll, but sadly it was closed to the public on the day we visited.

From the gate opposite the altar, steps lead down to a beautiful garden with lemons, oleanders and pomegranates, the ‘Latomia del Paradiso’, the largest and most famous of the twelve quarries excavated in ancient times, and since then one of the great sights of the city. The size of the quarries testifies to the colossal amount of building stone used for the Greek city and for Dionysius’ famous fortifications… By following the path you will see a tall isolated column of rock, the only surviving support for the roof of the enormous cave which the stone-cutters had formed, both to reach the fine quality limestone deep under the surface, and to shelter themselves from sun and rain. The great blocks of stone fell when the vault collapsed during the 1193 earthquake.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

“By following the path you will see a tall isolated column of rock, the only surviving support for the roof of the enormous cave which the stone-cutters had formed…”

Tucked away under the back of the Greek Theatre we found a small corner of the quarry that still retains its roof, the ancient excavation known as the Ear of Dionysius.

The path continues to the Ear of Dionysius (Orecchio di Dionisio), a sinuous artificial cavern, 65m long, 5-11m wide, and 23m high, in section like a rough Gothic arch. Its name was given to it by Caravaggio in 1608. Because of the strange acoustic properties of the cavern, it has given rise to the legend that Dionysius used the place as a prison and, from a small hole in the roof at the far end, heard the whispers of his captives. Before Caravaggio, local people called the cave the ‘grotto of the noises’. It amplifies every sound and has an interesting echo, which only repeats each sound once. Now it is filled with the strange echoes of noises made by pigeons which nest here. Once your eyes get accustomed to the dark you can walk to the far wall. The entire surface bears the marks of the slaves’ chisels and you can see the regular size of the blocks they were cutting: exactly one square cubit.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

L’Orecchio di Dionisio o Dionigi è una grotta artificiale che si trova nell’antica cava di pietra detta Latomia del Paradiso, sotto il Teatro Greco di Siracusa.

Next door we found – the Grotta dei Cordari, named after the rope-makers who worked here for centuries. The vault of this picturesque cavern is supported by huge pillars and the walls are covered with maidenhair ferns and coloured lichens. Access, unfortunately, is prohibited because of its perilous state.

The Roman Amphitheatre is an imposing building, probably of the 1st century AD, partly hollowed out of the hillside. In external dimensions (140m by 119m) it is only a little inferior to the one in Verona. Beneath the high parapet encircling the arena runs a corridor with entrances for the gladiators and wild beasts; the marble blocks on the parapet have inscriptions (3rd century AD) recording the ownership of the seats. In the centre is a rectangular depression, probably for the machinery used in the spectacles. The original entrance was at the south end, outside which a large area has been exposed, including an enclosure thought to have been for the animals, and a large fountain. Excavations here have revealed the old road, mentioned by Cicero, and the base of an Augustan-era triumphal arch directly to the east of the amphitheatre. The stone sarcophagi laid out here were found in the necropoleis of Syracuse and Megara Hyblae and brought here by Paolo Orsi.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

Our ticket to Neapolis Archaeological Park also entitled us to visit the nearby Museo Archeologico Regionale Paolo Orsi – This museum, dedicated to the great archaeologist Paolo Orsi, superintendent of antiquities from 1895-1934, has one of the most interesting archaeological collections in Italy, especially representative of the eastern half of Sicily. The material from excavations made by Orsi himself is outstanding. The collections are displayed in an unusual, low-level functional building in the shape of a broken triangle designed by Franco Minissi in 1967 and opened to the public in 1988.

We started our tour in the basement, in the Medagliere, the numismatic collection. Mostly I had no idea what I was looking at, I just clicked my camera magpie-like at whatever bright shiny coins caught my eye. There were labels but the information took some unravelling and I didn’t want to attract attention by taking too many pictures. I got the feeling photography was not really approved of.

The exceptional numismatic collection includes coins from the Greek cities of Sicily and southern Italy, together with Roman, Byzantine and Islamic coins, the first coins minted by the Normans, followed by Swabian, Aragonese and Spanish examples. The first coins issued on the island are from Naxos, showing Dionysus or Silenus and bunches of grapes; the earliest go back to about 525 BC. Beautiful examples were also made in ancient Katane (Catania); see the splendid tetradrachm with the head of Apollo, made by Herakleidas at the end of the 5th century BC. Coins from Gela show Zeus as a human-headed bull. Ancient Syracuse was famed for the beauty of its coins minted from the late 5th to the early 4th century BC, and some of the finest of these can be seen in Case 16, mostly in silver, but you will also find a gold coin showing Herakles strangling a lion. Among the rarities from the famous Floristella collection is a small gold coin of Messana (Messina) showing a hare on the obverse and a chariot drawn by mules on the reverse. There are also interesting examples of the art of Sicilian goldsmiths, from prehistory to modern times, with lovely seal-rings from Sant’Angelo Muxaro, rings and Byzantine earrings from Pantalica, and necklaces.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

This one, Head of Athena, was attributed to Eukleidas, a renowned Ortygian medal-cutter.

Looking at these beautiful handmade miniatures it’s hard not to regret the loss of a tangible token of currency, surrendered for the flippant exchange of a binary code. Give me that old time communion.

Tomb door from Castelluccio

A stand of goddesses

Statue of a headless mother goddess breastfeeding twins

(I’ve heard that can make you lose your head)

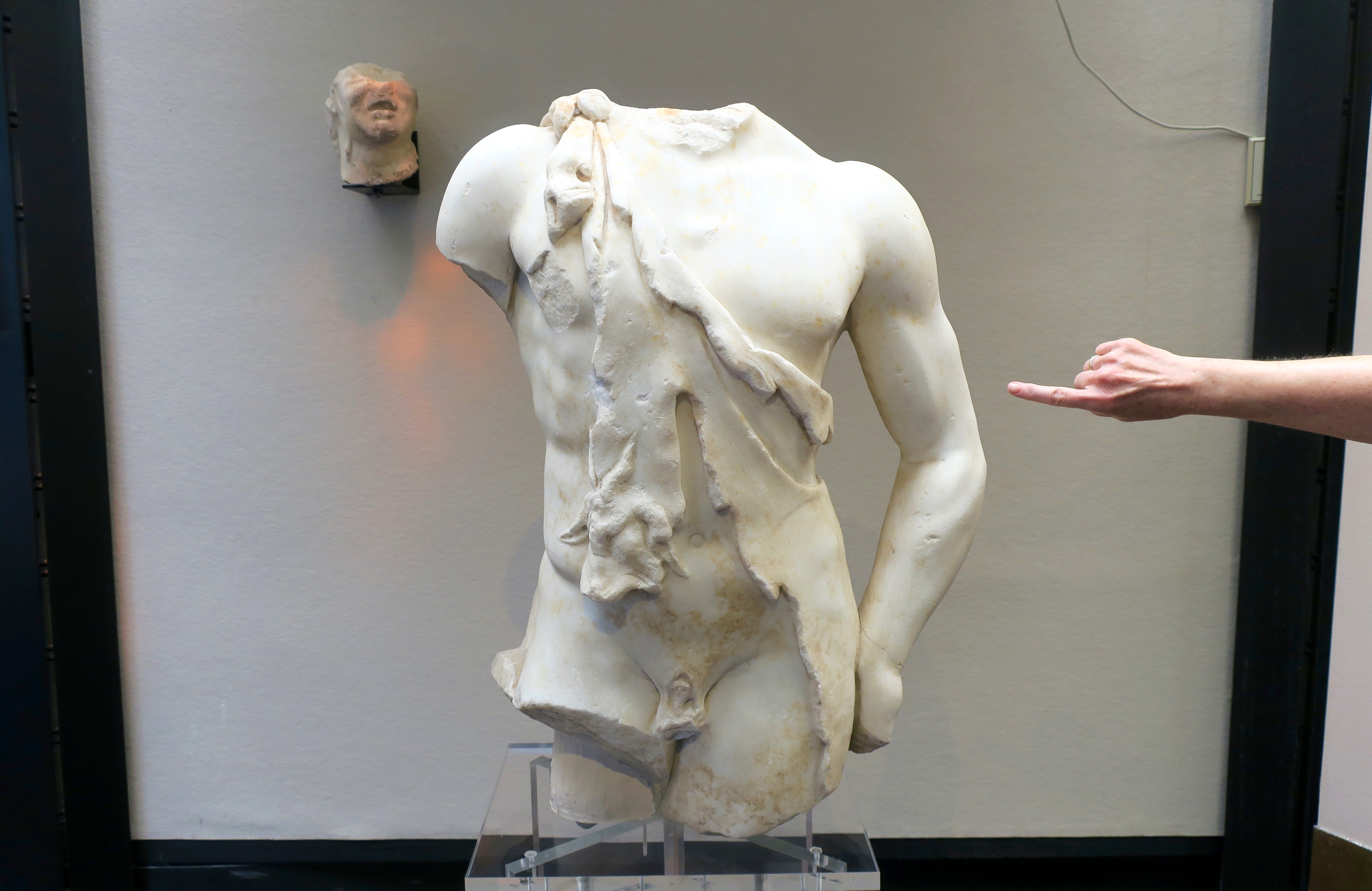

Hands & heads

Terracotta statuette of an ithyphallic dancing Silen raising a cup (520-480 BC)

A courtyard filled with trees of heaven

Terracotta figs – food for the afterlife

Two goddesses

(Susan Sarandon & Sophia Loren)

The Landolina Venus

The highlight, however, is the famous ‘Venus Anadyomene’, (emerging from the water), an Imperial Roman work inspired by Praxiteles’ famous Cnidian Aphrodite of the 4th century BC. Found in Syracuse in 1804 by the aristocrat and amateur archaeologist Saverio Landolina, she was greatly admired by Guy de Maupassant, who came purposely to see her in 1885 and left a vivid description of his emotions when he saw her: ‘It is not woman poeticised, idealised, divine or majestic like the Venus de Milo; it is woman as she is, as she is loved, desired and should be embraced’.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

A carved gladiator’s skirt decorated with gorgon masks

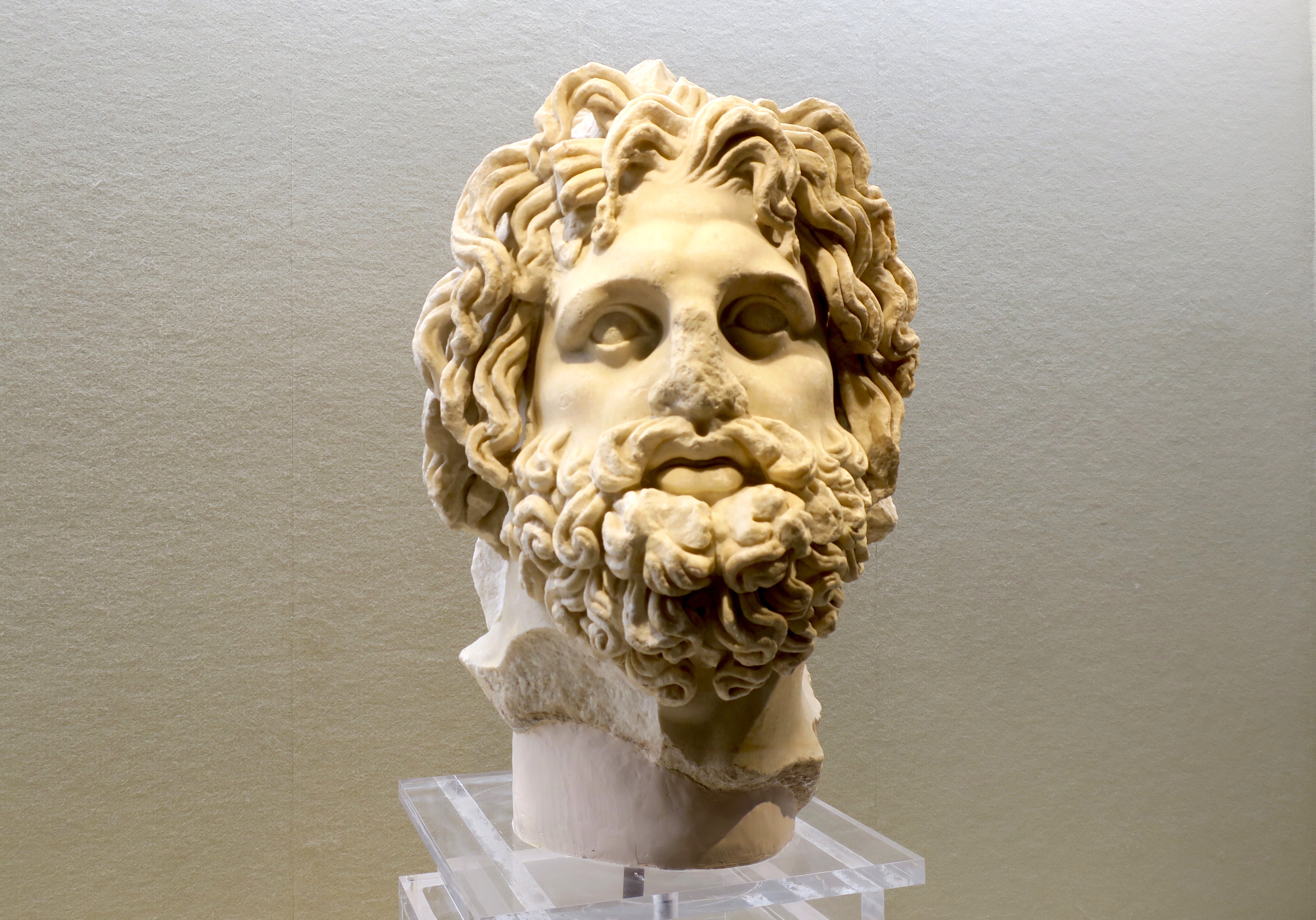

Head of a god

(Jim Morrison)

Sarcofago di Adelfia

As we approached the final gallery an attendant abruptly drew a rope across the entrance and told us the museum was now closing, and all of a sudden we were denied access to the last part of the puzzle.

This section is devoted to a somewhat shadowy period in the history of the city. Christianity is no longer a forbidden cult but times are difficult, epidemics and pirate raids are frequent, and the economy suffers accordingly. The highlight of the collection is the Sarcophagus of Adelphia, a white marble coffin carved in high relief with episodes from the Bible, including the Nativity, Flight into Egypt, and Massacre of the Innocents, surrounding the central medallion with the magistrate Valerius and his wife Adelphia.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

Outside, a carved tree, curiously perforated, and a chorus of birdsong.

The vast tepee-shaped sanctuary of the Madonna delle Lacrime, Our Lady of Tears was begun in 1970 to enshrine a small mass-produced plaster image of the Madonna, and inaugurated in 1994. The figure is supposed to have wept for four days in 1953 in a nearby house. The sanctuary (by Michel Andrault and Pierre Parat) incorporates a late Roman tomb and numerous ex-votos in the crypt. The huge conical spire (98m high, including the statue) towers incongruously above the city.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

And then later, back over the bridge in Ortigia, by the bronze statue of Archimedes, a spiral set into the marble base, a spiral to square the circle, to refresh and to rewind and to let us go round again…

Did virtually the same visit two years ago. But early on cold first day of the year and we had the place all to ourselves for a while. Thanks for all the memories!

Thanks Josie, nice to think we were following in your footsteps! It’s an amazing collection of ancient sites and sights, hot and crowded when we were there, and sorry not to see the quarry paradise garden, but dazzled by the bright histories.