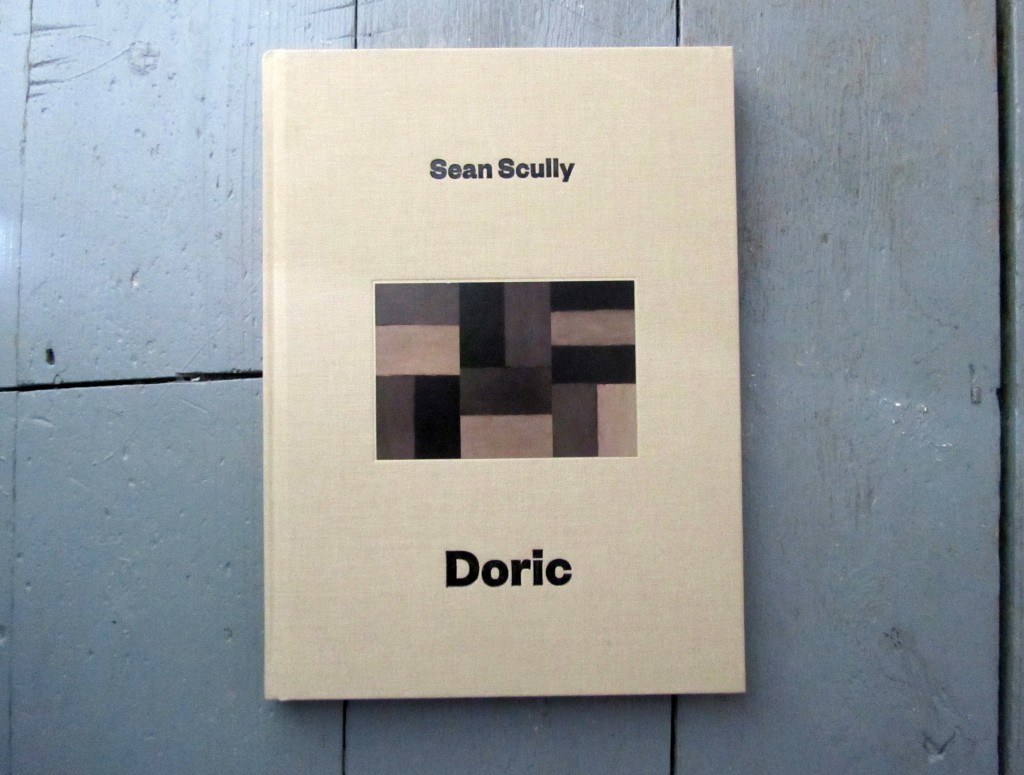

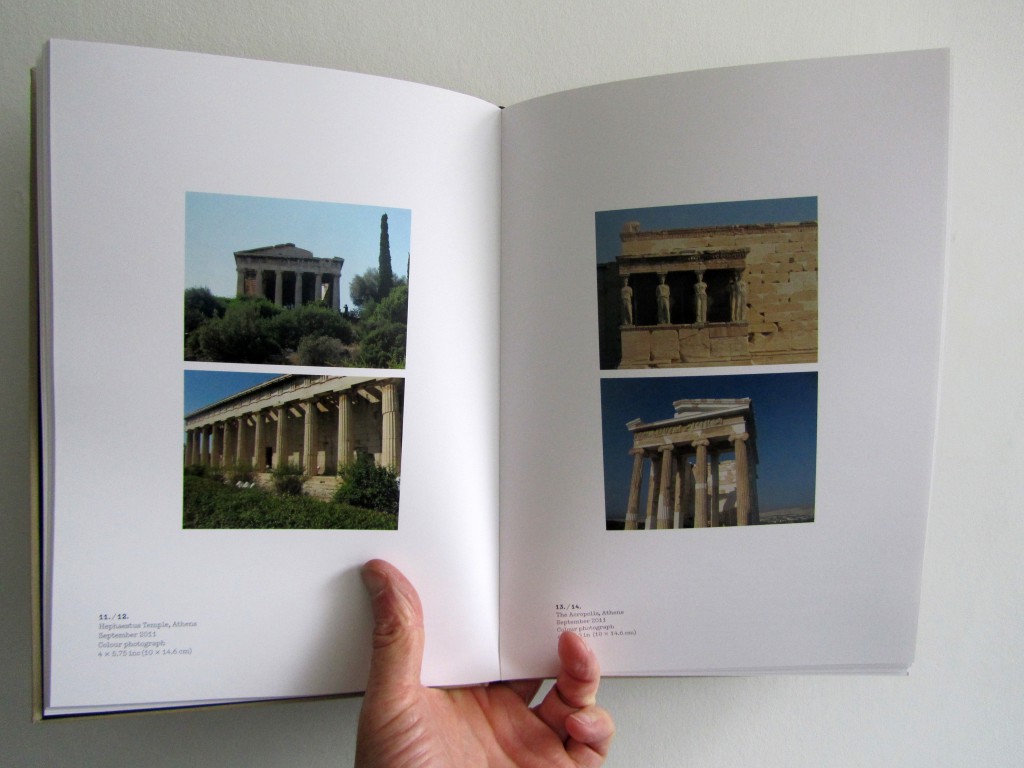

Doric is the title of a family of paintings by Sean Scully, an ongoing series inspired by ancient Greek architecture, first shown as a group at the Benaki Museum in Athens last year. Since then there have been Doric exhibitions at IVAM in Valencia, the Hugh Lane in Dublin and the MACM in Mougins.

The Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins is a tiny museum on four floors with a surprisingly large and diverse collection. I was unsure of the figure abseiling down the wall but the couple facing each other is Reflection by Antony Gormley, more familiar from the Euston Road.

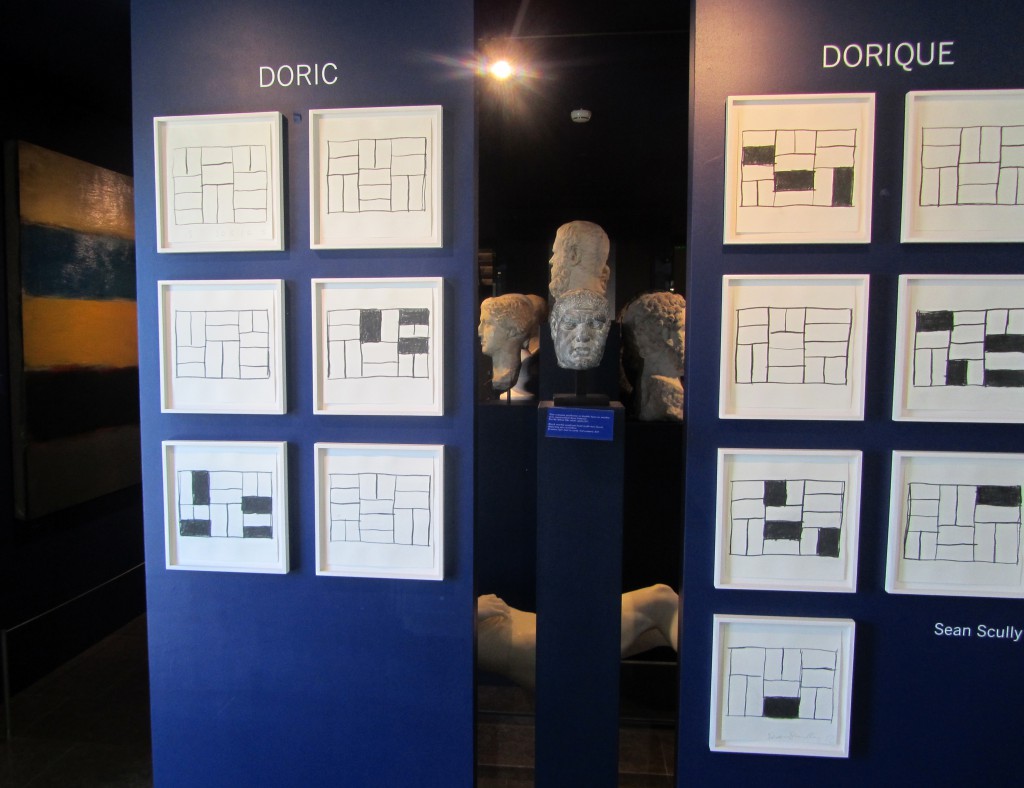

The Doric exhibition was also tiny and was introduced by a series of thirteen charcoal drawings, the opening bars of an unresolved sequence, a cycle from dawn to dusk, a calendar of days and nights.

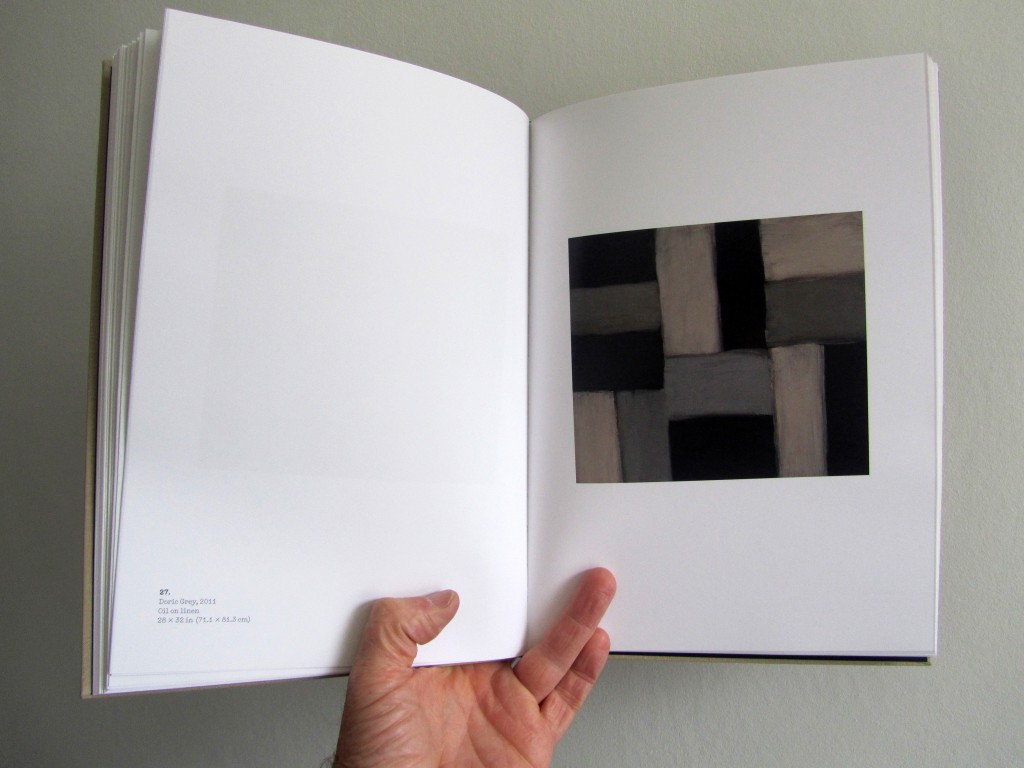

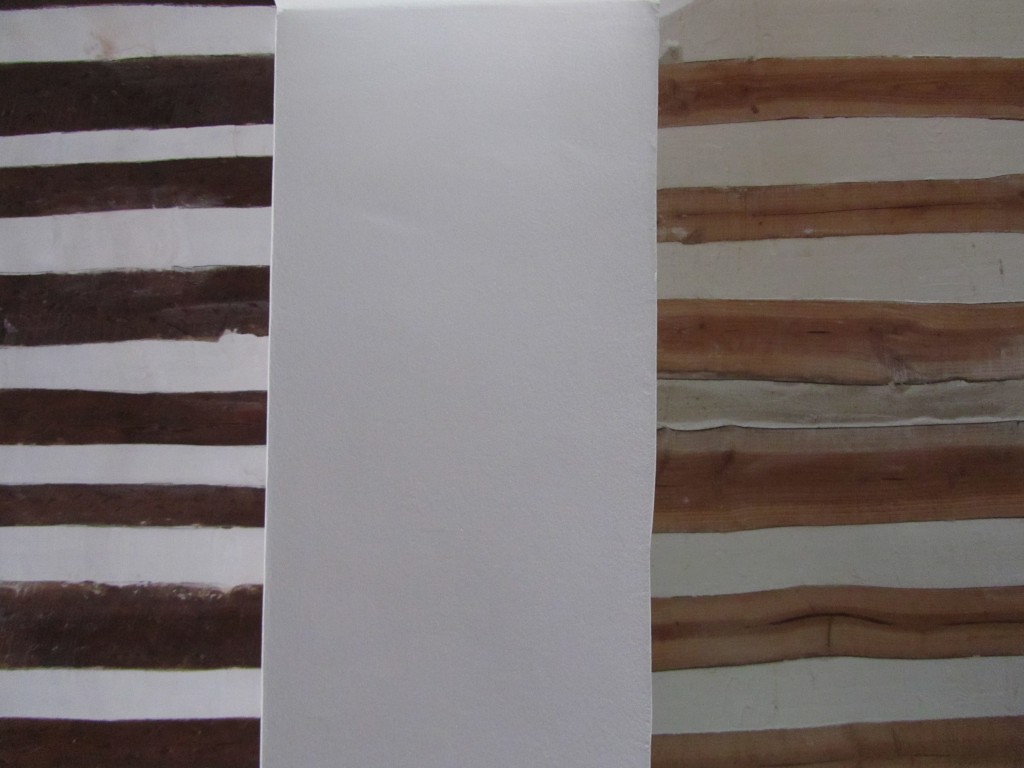

The Doric paintings feature Scully’s signature binary system of handmade horizontal and vertical blocks, mostly in monochrome with varying degrees of light and shade and some occasional colour.

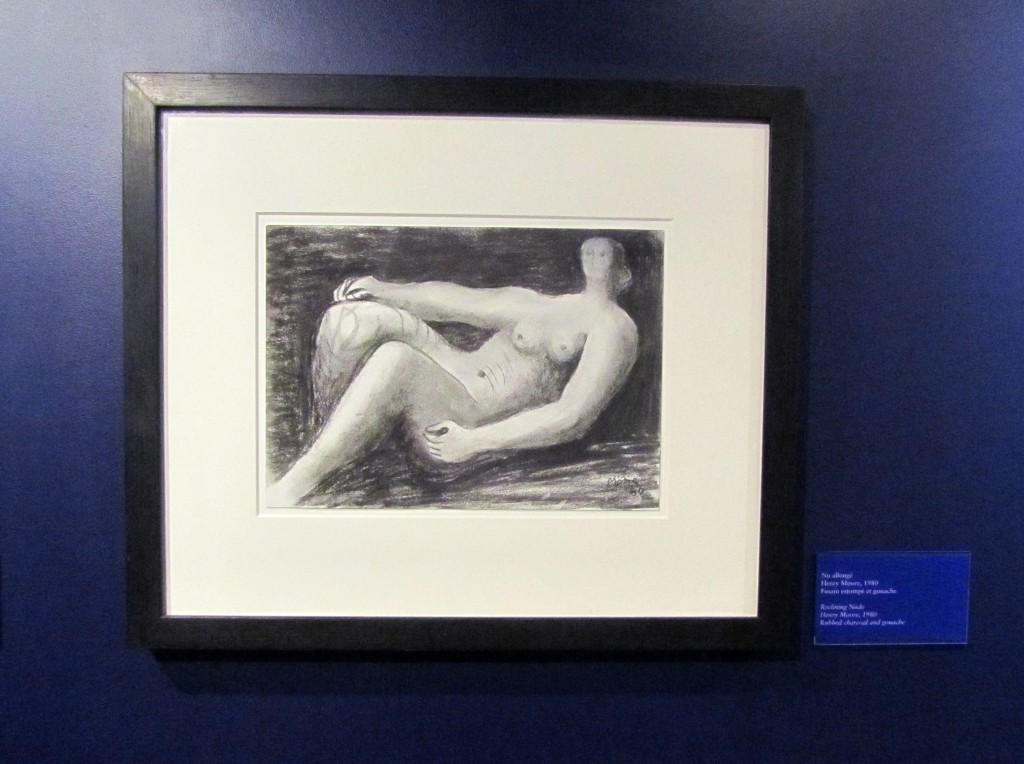

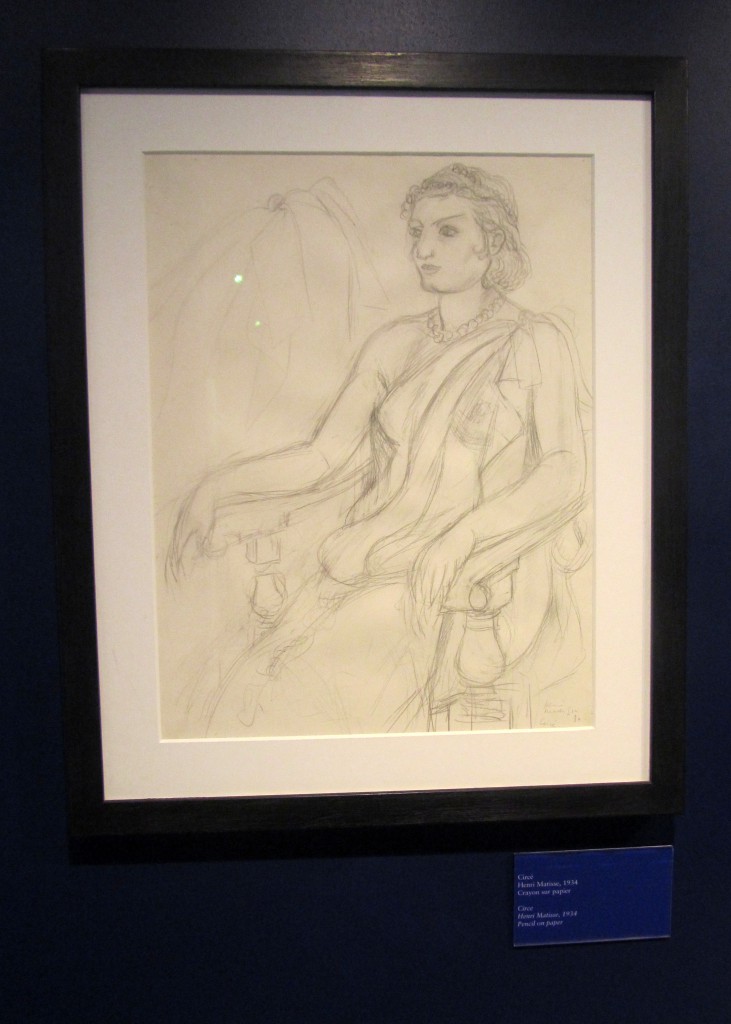

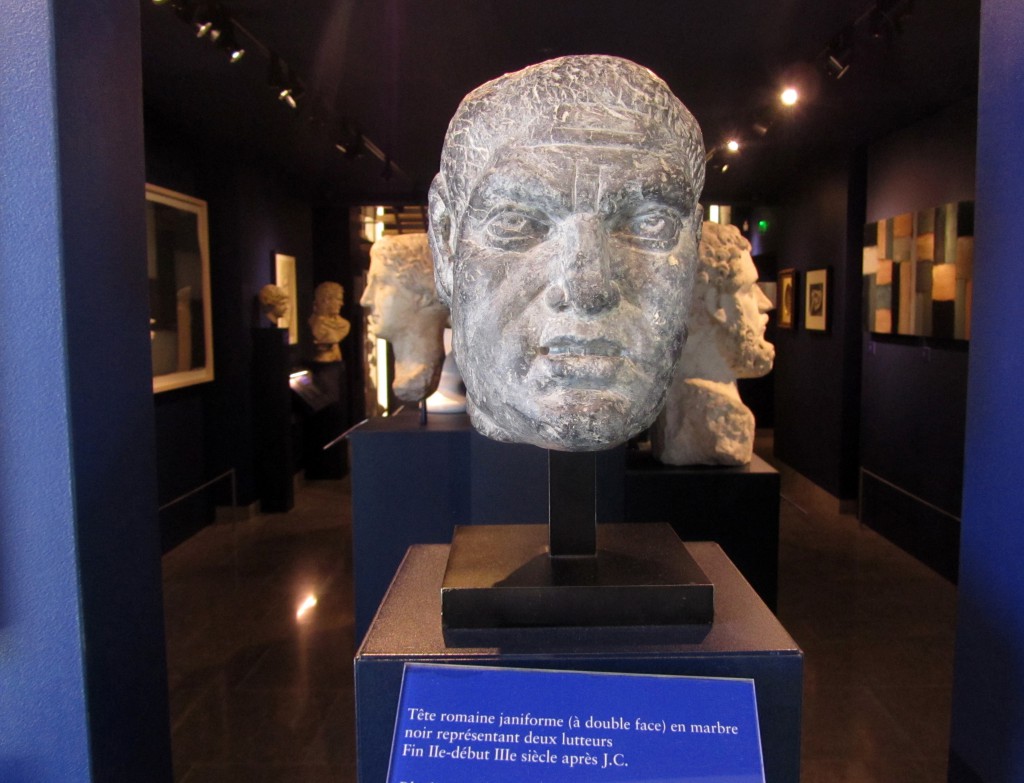

They were hung in the first room on the ground floor around a central display of ancient and modern classical portrait busts by Maillol, Sosno, Quinn, Anon and alongside drawings by Moore and Matisse.

Sean Scully’s paintings were in good company. This Roman carved Janus head, double faced, open & closed, positive & negative, dark & light looks suspiciously like a portrait of the Scully as a young man.

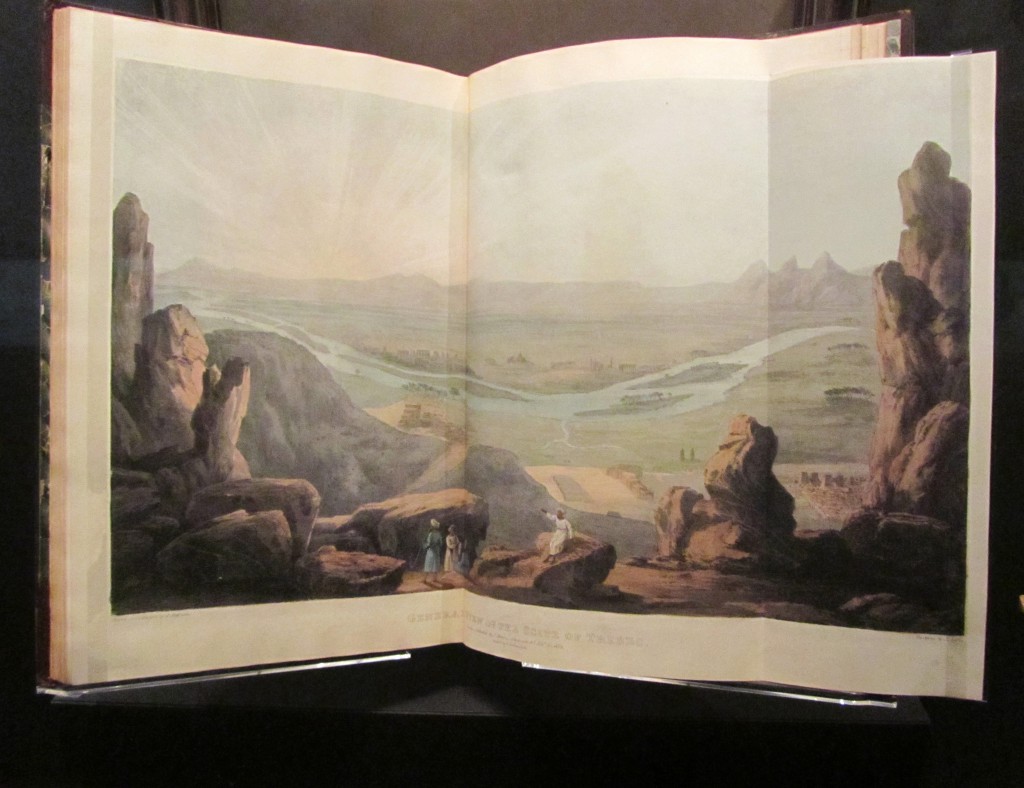

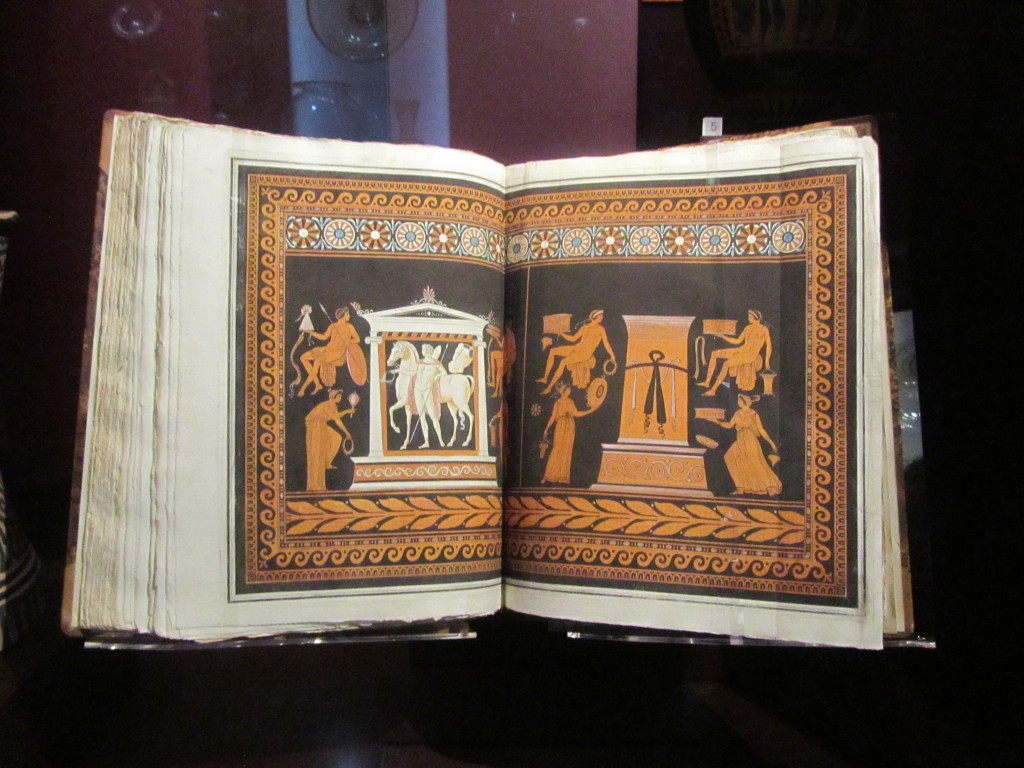

The ground floor is classified as Célébrités. On the floor below is Egypte Antique, Thebes, Isis, Ptah.

On the first floor, Gods & Goddesses, there was Andy Warhol’s Birth Of Venus, Yves Klein’s Venus Bleue, Salvador Dali’s Venus As A Giraffe plus other anonymous effigies of Venus and Aphrodite.

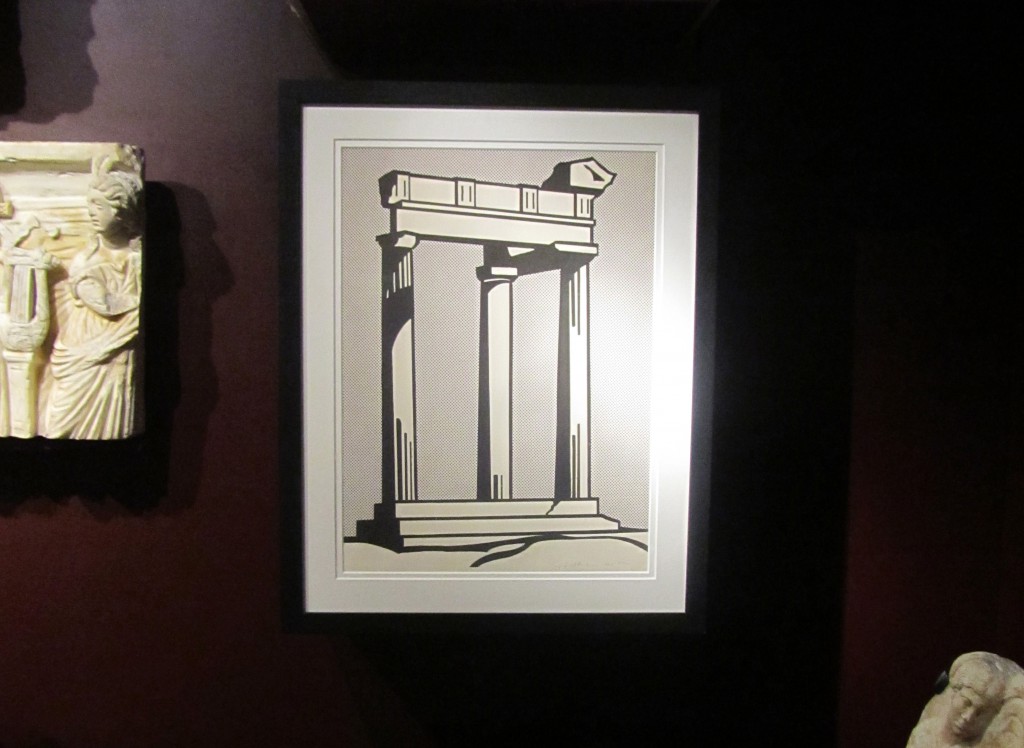

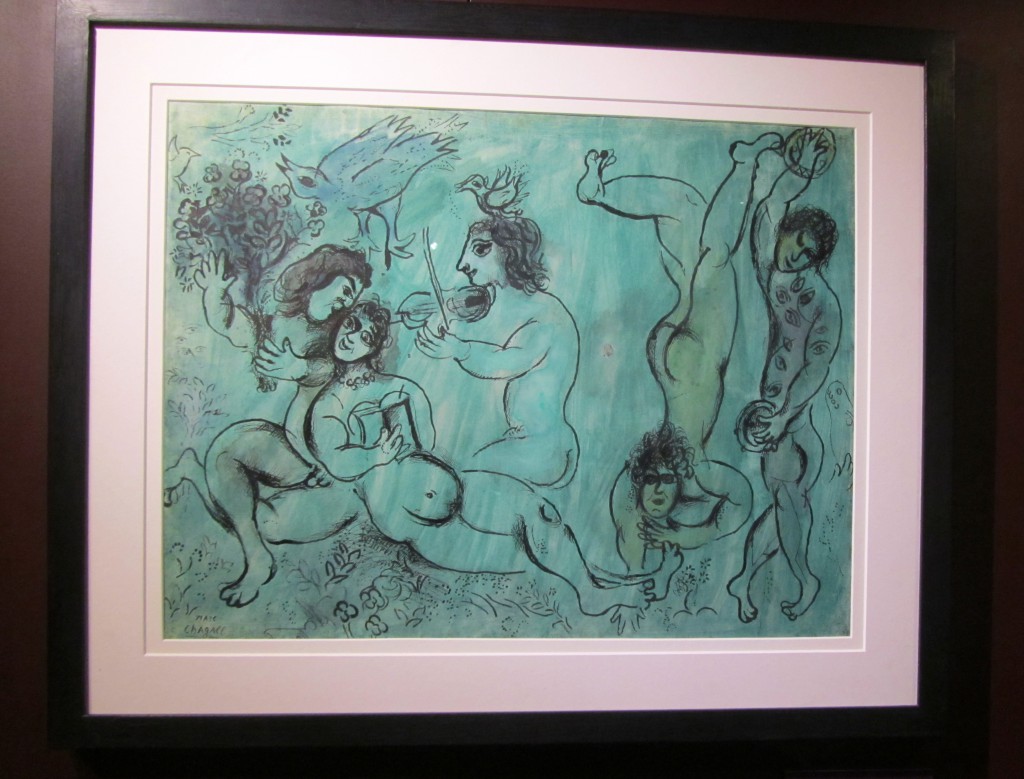

There was a Bearded Man Crowned With Vine Leaves by Pablo Picasso, a cabinet of Etruscan gold, a Temple by Roy Lichtenstein, a terracotta vase by Keith Haring, a Bacchanal by Marc Chagall, a two faced janiform marble bust of Bacchus & Ariadne and finally, on the second floor, the Armoury.

But all these treasures were just a diversion from the real reason for our visit, a little taste of Doric.

The exhibition was disappointingly small, though given the size of the museum it could hardly have been any bigger. It was a tantalising teaser for the much larger versions in Greece, Spain and Ireland.

The foreword to the catalogue is by Oscar Humphries:

I first saw one of Sean Scully’s ‘Doric’ paintings at an exhibition held at the Timothy Taylor Gallery in London. This painting, ‘Doric Brown’, now hangs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, my home town. I remember Sean telling me that he wanted to make more of them, and that they were important. Standing in front of the large ‘Doric’ paintings this is obvious. First they overwhelm, then they force us to consider art, history, and finally ourselves. I was struck by how they behaved like great architecture – something about their structure and their scale humbled me, as ancient temples humble us.

Nearly three years later, there are indeed more ‘Doric’ paintings and they will be shown, en masse for the first time, in Athens – the city which is their genesis. Sean Scully says that “it is very rare that an artist’s intentions are met so directly by location.” This show, and the ‘Doric’ exhibitions in Spain, Ireland and France that will follow it, are a testament to the universal in art: that fragile line that links all great art, from the ancient to the modern, which one can trace from the murky recesses of art history into the studios of our best living artists.

The catalogue includes an essay, Breaking Doric Down, in which Kelly Grovier contrives this nice comparison with Oscar Wilde:

…For those unfamiliar with the classical architectural orders, ‘Doric’ and its cognate ‘Dorian’ may bring to mind instead the protagonist of Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, a novel whose gothic decadence may initially seem at furthest remove from the soul of Scully’s paintings, and the slow erasure of phenomenal sense argued for here. Certainly few works feel more temperamentally opposed to the spirit of Scully’s stark ‘Doric Grey’ than the famously debauched decay of Ivan Albright‘s egregious 1943 portrait of Wilde’s Dorian. Nonetheless, when one considers how Wilde reverses the permanaence of art versus the perishability of life – the portrait shows the corruptions of age and vice, while the subject remains gloriously unchanged – a dialogue between the respective visions of the Irish novelist and the Irish painter becomes truly intriguing. For Wilde, art is a plane on which life can be outlived, not because of naive fallacies asserting its permanence or immutability but because it is more vital than life and thus more susceptible to the vicissitudes of disintegration and change. Scully’s ‘Doric Grey’, in other words, like Wilde’s ‘Dorian Gray’, has endeavoured to depict the undepictable, to make art do what we rationally know it cannot: to see the space between the real and the imitative, the tonal gap between life and death.

Outside the cicadas drone in the midday heat. The air vibrates all the way to the distant Alps. I’m buzzing with Scully’s enriched minimalism and it’s easy to begin to see the world through his eyes.

Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins: Doric

Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane: Doric

Instituto Valencia d’Art Modern: Doric

The Benaki Museum, Athens: Doric

Great post. Loved that end section of the world through Scully’s eyes.