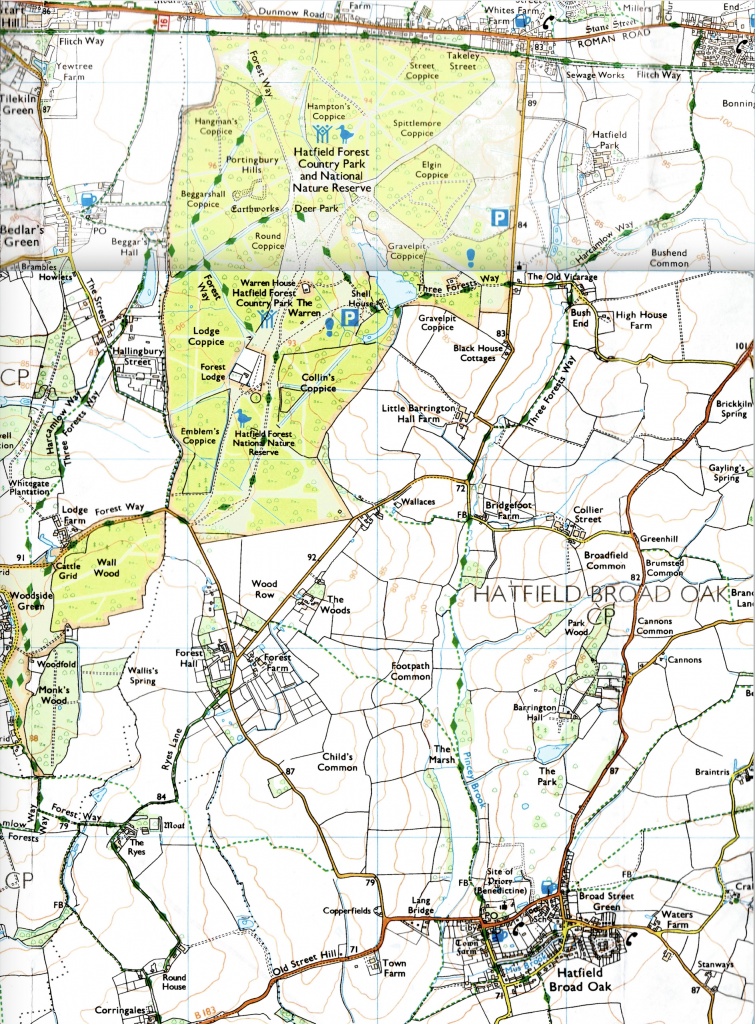

Another Covid walk, this time back in early September last year. We’d been wondering about returning to Hatfield Forest for months, but each time we checked the National Trust website we were discouraged from visiting. The car park had to be booked in advance, and whenever we tried it appeared to be full. You will be turned away if you arrive without booking. So, in the end, we decided to drive to the nearby village of Hatfield Broad Oak and walk to the forest from there.

We parked below the church and came down through this cow pasture to a footbridge over Pincey Brook, winding its way through the water meadows.

Whenever we set out on a walk like this I always have to rush up and greet the first tree we see. And I think this field maple was pleased to see us too.

The brook splits into three and forms a lake surrounded by marshland where last we saw egret, heron and lapwing. Today we found only feathers. I’d guess they’re pheasants’, but had they fallen or were they plucked?

Pheasants are bred and reared in captivity, and then released to wander lost and disoriented through the countryside. Intrepid hunters are allowed out at playtime to come and find them, ready or not, and to shoot them for fun.

But better to pick the feathers like flowers for fun.

Plaited oak

Threaded hops

Twisted willow

We’d walked by hedgerows full of sloes and draped with hops, along the feathered path, and perhaps it was just as well we hadn’t driven this way.

At the top of the hill we entered the forest by Doodle Oak Gate. It felt slightly transgressive, like we were breaking the rules by avoiding the car park and coming in through the back door. But it was fine, we needn’t have worried. There was more space and less people than on our most recent visit to Hampstead Heath, which had felt decidedly dangerous by comparison.

We breathed a sigh of relief, happy to be among the trees. They filter the air and lockdown the virus. Its doublespeak is safely impeached, rendered harmless and reunified with Europe. There is a balm in Hatfield Forest. Its mycorrhizal networks reach out to Stansted Airport, from where they are transported around the world to cool global warming.

Writing these words in January, Hatfield Forest is a midwinter day’s dream.

We diverted off the main path into scrubby woodland to our left, following a winding track along the edge of the forest. I had a map with me, bought on a previous visit, with a big red arrow pointing to this neck of the woods. The caption reads:

Largest Ancient Oak. Tucked into the scrub here is the largest Oak tree in the Forest. It is an ancient Oak pollard, but probably hasn’t been cut for 150 years.

There were a few oaks, but not many, and none of them looked ancient.

Mostly we encountered ash trees.

The Tree at the Centre of the World

We emerged into a clearing where we found a forest ranger stacking logs on the back of his Gator. I showed him our map and asked if he knew how to find the Largest Ancient Oak. “I think that map’s out of date” he said, as he considered where to find the tree. “Down here, turn right through the gap, and go on until you get to the horse chestnut. There’s an old oak behind there, deep undercover. Maybe that’s the one.”

We cut through a hedge and along Elm Walk to the horse chestnut tree.

It’s impressive, tall and wide, a great stand alone tree. We enter beneath its canopy, a gateway to the understorey, where we wend our disoriented way through brambles and nettles and trees of all kinds, until we find one that looks like its been here forever.

But I think we’re too late. This oak tree is but a shadow of its former self, it is leafless and past its best. Its hollow trunk is a vent for the underworld.

We returned to the main ride through the forest. This wide greenway is here called Old Ladies Drive. As it progresses further north it’s known as London Road. We walked as far as Forest Lodge then through Lodge Coppice. We had no agenda now, having found the Largest Ancient Oak (maybe), we were free just to follow our feet. As we walked a buzzard circled overhead.

Hatfield was a wooded Forest, but it was not all woodland. It was, and still is, divided into coppices and plains. The coppices are definite woods of between 26 and 60 acres, each surrounded by an earthwork called a woodbank. There were seventeen coppices, of which eleven survive; they now comprise a little over half the area of the Forest.

The plains are grassland; they are grazed by cattle and deer, and formerly by sheep, goats, horses and geese. They are set with ancient oaks, maples, hornbeams, ashes and hawthorns. Tongues of plain penetrate between some of the coppices. Here and there in the plains, and forming part of them, are scrubs, thickets of hawthorn and young trees with ancient trees embedded in them. Although there have long been scrubs in the Forest, they are not individually ancient, nor are they defined by woodbanks.

Also in the plains are the Warren – a term which implies the husbandry of rabbits as Forest does that of deer – and two buildings, Forest Lodge and Warren Cottage.

Oliver Rackham: The Last Forest

A magic apple tree

We wandered aimlessly through Lodge Coppice. Mostly it’s a mixed wood of maple, ash and hazel, but also many notable ancient oak coppice stools.

A romantic, and nearly unique, feature of the Forest are the huge coppice stools of oak, hollowed and gnarled into Arthur-Rackham-esque shapes, some of them nearly as tall as pollards (Plate 18). In the western coppices they can be so many as to dominate the woodland. They are all ancient stools, sometimes more than 9ft across, and have been cut many times; they are not to be confused with casual regrowth from the stumps of timber trees.

Oliver Rackham: The Last Forest

We’d left the path and stumbled around through the trees, drawn towards the next oak coppice stool, tripping over fallen branches, going round in circles and getting lost, until eventually we came out onto another path and suddenly I was stopped in my tracks. Over to our left, partially obscured by the surrounding foliage, I could just discern the dancing shapes of a great writhing multi-stemmed oak. This was a remarkable and exceptional tree.

I was fascinated, pulled into its orbit by outstretched branches, captured by welcoming tentacles and spun around in a slow dancing green embrace.

I was reeled in.

This is another winding tree to spin the yarn of centuries.

How many times must it have been cut back and regrown again? It may not be the largest tree in the forest but I can easily imagine it to be the oldest.

It was only later, when we got home and I looked at an earlier blogpost I’d written about a previous visit – Hatfield Forest & Hatfield Broad Oak – I saw from the map there that this must be the Palm of Hand Oak.

There’s another, behind it, but with fewer fingers.

We continued along Thurley’s Straight. Behind us a thriving hedgerow down the middle of the ride, and before us a freshly exposed drainage ditch, the hedgerow razed to the ground and disappeared.

We are heading for Beggar’s Hall Coppice.

At Old Dick’s Ride we’re diverted because of a ‘Dangerous Tree’.

We come upon a small corner of preserved ground.

It’s no bigger than a football pitch but you’d twist your ankle kicking a ball around here. It’s haphazard with anthills and a haven for wildflowers.

And this is a puffball not a football. But it’s the same size.

There are lots of them here.

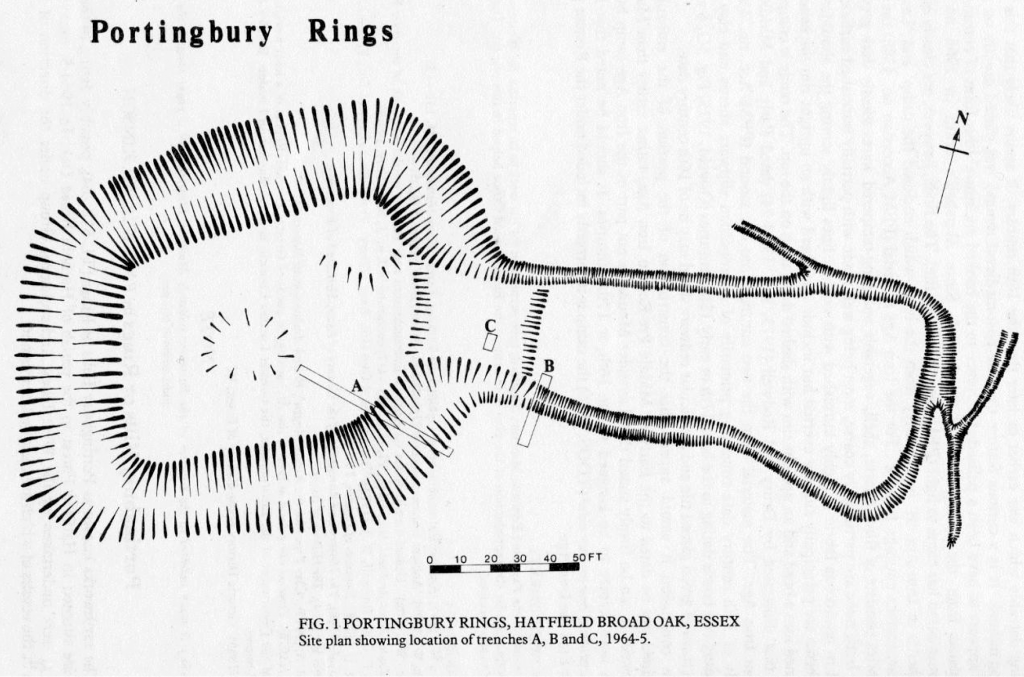

This small patch of rough ground, covered with low mounds and ditches, is known as Portingbury Hills or Portingbury Rings, the unassuming visible remains of an Iron Age earthwork. A great variety of wild flowers grow here, including Cowslip, Marsh Thistle, Hedge Bedstraw, Houndstongue, Valerian, Brighteye, Common Gromwell and some Orchids. It is a good area for butterflies such as the Meadow Browns and Speckled Wood.

It has been suggested that Portingbury Rings was a prehistoric observatory, aligned with other earthworks along the River Cam to Wandlebury.

This theory would give Hatfield Forest a monument, as old as Stonehenge, which might even have been ‘the inspiration behind the development of Western Civilisation’.

Oliver Rackham: The Last Forest

So this is where it all went wrong! But read on a little further and it quickly becomes apparent that Dr Rackham is not convinced. His best guess is that this curious structure might once have been just a fortified farmstead.

Hawthorn & mistletoe

We went down to Shell House Café for tea and cake, then around behind the lake, to an area on the map called America. This is one of its mansions.

A gate led us to a boardwalk through the trees. I heard a knocking sound and stopped to listen. I thought perhaps it was a woodpecker. But then I saw a nuthatch on a tree beside me, maybe 20 feet away. I took lots of very quick photos, but too quick to really take in what I was seeing.

I was not really looking, just pointing the camera and clicking the shutter.

From the heavy texture of the bark I’m guessing this must be an elm tree, though I don’t remember seeing any in the forest. The nuthatch has wedged a hazelnut into a crevice and is hacking at it to split it open.

Vertically, from above. It’s an acrobatic bird.

And then, in a blink, it was gone (top left).

So it was down through Collin’s Coppice along Two Oaks Ride, though there were few oaks to be found, mostly it was hazel and aspen and ash.

Down Beech Tree Ride, out of the coppice and into the plains, where cattle and deer traditionally graze. Sometimes they can be found in the scrubby woodland areas too, but they are kept out of the coppices until the new growth is strong enough to survive their browsing. Today there were none to be seen here, perhaps they were in another part of the forest, in Bush End Plain or Takeley Hill or Elman’s Green.

Hatfield Forest in the World of Wood-Pasture

Wood-pasture, of one sort or another, runs deep in human nature. It extends through Scandinavia into Finland; down through Europe, via the pollards and Lärchenwiesen (larch meadows) of the Alps and the wood-pastures of the Appennines into Greece, and on into the Himalayas. Pollards, grassland and oakwood still cover mile after mile of the Pindus mountains of Macedonia; there are huge numbers of pollard oaks, cut in a different style, in the mountains of east Crete…

Hatfield Forest demonstrates a practice that goes back long before the idea of Forests; our Neolithic ancestors might well find themselves at home in it. In most of the world’s wood-pastures the trees’ chief duty is to grow leaves on which to feed the animals; in England, at least in historic times, the trees have been meant for timber and wood, with leaves only as a minor product. As far as I know, the English compartmented wood-pasture is a supreme elaboration of the system. Hatfield Forest is the unique survival, in full working order, of this aspect of human affairs at its zenith of complexity.

Oliver Rackham: The Last Forest

And it’s a great place for a physically distanced ramble, a woodland wander, an arboreal constitutional, to stretch our legs and to stretch our eyes. There is a lot to see. Each footstep is a click of the camera, each walk is a collection of sights, I go foraging for photos, for eyefuls of trifles and truffles and trees full of treasure. A forest of photos to scroll down the screen.

We go with the flow and follow our feet, from photo to photo, no words just pictures, walkative not talkative, all the way back down along Pincey Brook.

Whoa! Wait a minute. There’s someone waiting for us at the kissing gate.

This young bull seemed quite protective of his mate, stubbornly refusing to move and blocking our way. She was not at all concerned and ignored us completely. I said a few gentle words but he only snorted and stamped his foot. At which point I suddenly became really interested in the old cracked willow tree in the hedge beside us, and pretended that was why we were here. We didn’t want to go through the gate at all. Whatever gave you that impression? He went on snorting. We looked at Google maps and planned an alternative route, a 3 mile round trip back the way we’d come and then along the road to Hatfield Broad Oak. It seemed crazy, we were already almost there. And by this time the bull had backed off, but he was still watching us intently. We eased through the gate and kept as close to the edge of the field as we could, and with each footstep planning how we might leap over the barbed wire fence into the hedge. He watched us go, I could feel his eyes on the back of my head, all the way to the next gate.

And then there’s an aeroplane overhead, lifting off from Stansted. I’m drafting this blogpost five months later, wishing I was on that plane, free to spread my wings and fly away, free from lockdown, free of this government, back into Europe. It feels auspicious. It is 9:21 pm on the 21st of January. It is the 21st minute of the 21st hour of the 21st day of the 21st year of the 21st century. There are floods, there’s a plague, we’re ruled by liars and cheats. But we’re still here, and Hatfield Forest too. Still here, still now, still life.

※

Hatfield Forest | National Trust

Thank you for this – Hatfield Forest was a favourite destination when I was growing up – you’ve reminded me of the magic of forests and trees.

Thanks Jill, I hope I’ve inspired you to return to the forest. I’m longing to go walking again.

“The map was out of date. The tree had moved.”

What a great walk. Lovely photos too.

Thanks Josie, that’s a great tree. Does it move? I tried to ‘like’ your blogpost, it’s impressive, but my WordPress account is confused and won’t let me!

It has the capacity to move people and shelter deer but does not itself move, so far as I am aware. If it does, it carefully returns to the same location by first light.

“Stones have been known to move, and trees to speak.”

“…in times like these it is necessary to talk about trees”