We were in West Dorset at last and I was elated. I’d long wanted to drive these roads. We were in a maze of high banks and hedgerows, hidden from the wind, burrowing back down to earth, gone to ground.

But perhaps not best photographed from inside a car.

Highways and low-ways, byways and noways, deepways and holloways, all roads brought us by a slow circuitous route to our rented holiday home down at the end of the lane below Eggardon Hill.

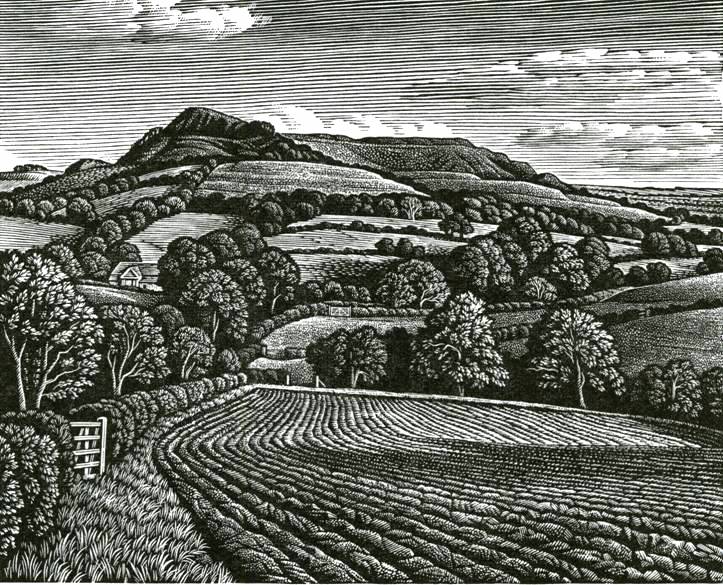

Next day, walking back from Nettlecombe, I stepped off the road into a field and took this photo of Eggardon on my phone, then later realised I’d stood in pretty much the same spot as Howard Phipps.

It was Howard’s love of Eggardon that had inspired us to come down to Dorset for a closer look, so we invited him to come and join us for a walk.

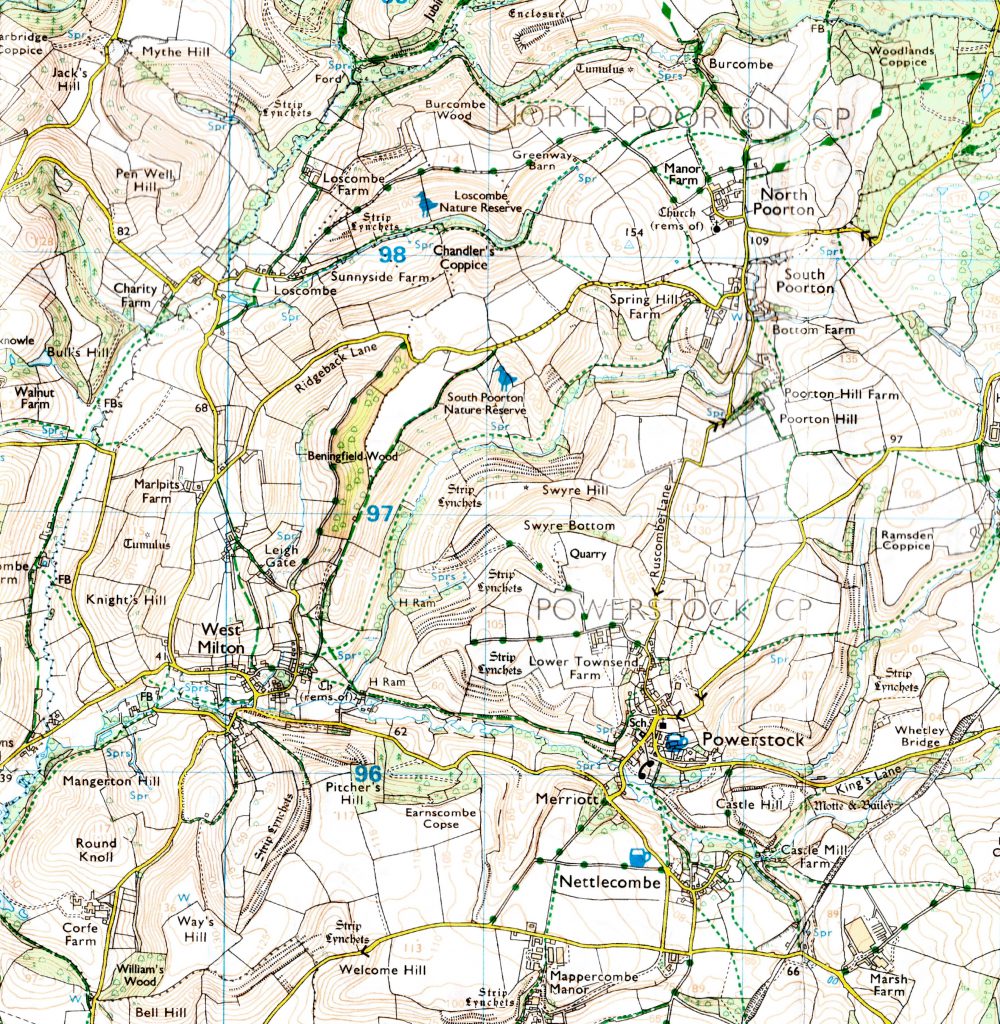

I’d been given directions for a circular walk from West Milton by Paul Newman, one of a series he’d written for the Bridport Times. Paul, like Howard, is a member of The Arborealists, a group of artists inspired by their shared love of trees and woodland landscapes.

We extended the walk a little by starting from Powerstock and walking along the river path to West Milton.

We entered the village under a shady walnut tree beside the remains of St Mary Magdalene Church. We were headed up Ruscombe Lane to a nameless deep holloway that branches from it. I felt sure that Kenneth Allsop must have mentioned it in his book, In The Country, about his time in West Milton. I scoured it for references but there were none. But I did find this…

But I am happiest here in the intricate and moody countryside of south Wessex. There is nowhere like it, this one hundred square miles bounded on one side by the Great Heath – Hardy’s ‘haggard waste of Egdon’ – and on the other by the Great Marsh.

Crushed between are terminating rock seams from east and north, colliding in a mad pile-up. There is a tumbled anarchy of hills, contracted Pyrenees: long hogbacks of chalk, sheer limestone scarps, billows of down, knaps and knolls and batches, and high conelets of sandstone like emerald plum puddings.

Some visitors are uneasy. It is not just a matter of being swallowed in the remoteness and haunted antiquity of the land. There is also the sense of being conjured with, of hallucination. It is halls of mirrors in series and in receding rows, with results like the reversal of the expected in a Magritte painting. Take two steps in any direction and your surroundings are rearranged like the painted scenery of a toy theatre.

It is a geological madhouse. A new hummock inflates before your eyes; an unsuspected valley has unfolded. It is easy to feel disoriented. It is also, if you enjoy it, easy to allow yourself to be lost.

Old green-roads and driveways and tangled tracks wind into mysterious furzy coombs where on a summer afternoon you hear nothing but the bees and the wail of a soaring buzzard, and in winter perhaps the bubbling trill of curlews flighting down to the estuary saltings.

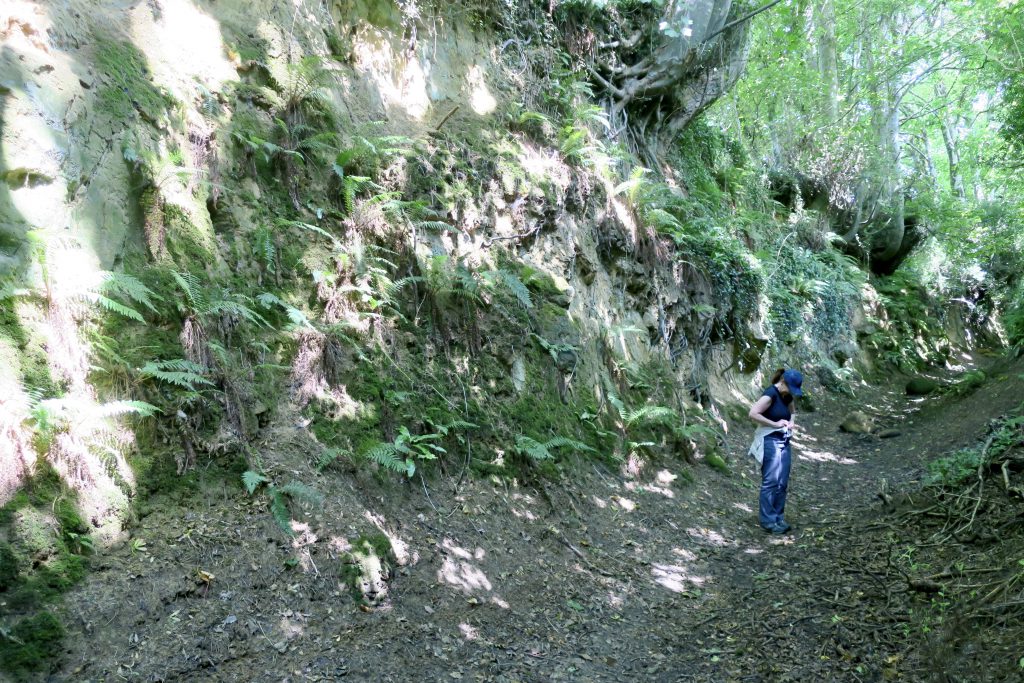

Even in the touristy summer months the lanes aren’t much used. Motorists eye them and turn tail, foreseeing a respray job after squeezing through those brambly clefts. So grass sprouts through the tarmacadam and some are dim tunnels roofed over by knitted boughs and draped with ferns.

We were already there, in a dim tunnel draped with ferns, when another, narrower and steeper, suddenly opened up before us and invited us in.

It felt like coming home. In a green shade, bathed in dappled leaf-light, I could have stayed here all day.

This was one of those walks that became imprinted and I would replay it as I lay in bed drifting off to sleep, retracing one step after another like counting sheep. Everything up until this point had been fast forward, but this was where it slowed down. Here we stepped into a sunken path and everything suddenly felt more ancient. It wasn’t that I started to imagine what had gone before, I didn’t witness historical events, I just felt more grounded, less animal, more vegetable, more part of the place.

We were all a little dazzled and mesmerised. Howard even took out his camera. He usually prefers to record a place with watercolour or pencil.

But here it was as if we were inside a pinhole camera, we were all part of the photograph, even now still slowly developing long after our brief exposure.

I think I left my heart there, held captive by tree roots and searchlights.

The lane ascends, climbing out of the holloway now with views through the trees across the adjacent valley.

The path becomes narrower so we proceed in single file. In places it is overgrown with brambles and nettles. We carefully unpick the tangled thorny branches and thread our way through the stinging leaves. Howard and I were both wearing shorts and for the rest of the day our legs were fizzing with a mild electric shock. Sue had sensibly worn walking trousers.

I’m in a reverie of rootedness, grown backwards down the generations to when we all lived closer to nature, and just for a moment I’m remaking all those little everyday connections that we’ve lost. Smells and sounds and…

Suddenly a deafening laughing call as a big green woodpecker comes swooping from the valley into the trees beside me. It clings to the bark of an ash tree and watches as I reach for my camera, then in the blink of an eye it’s gone, too quick for a photograph.

The path becomes steeper and narrower again, washed by heavy rains into a gulley. Here and there I could see tyre tracks, and it seemed like branches had been laid along the bottom of the path as a deterrent to mountain bikes.

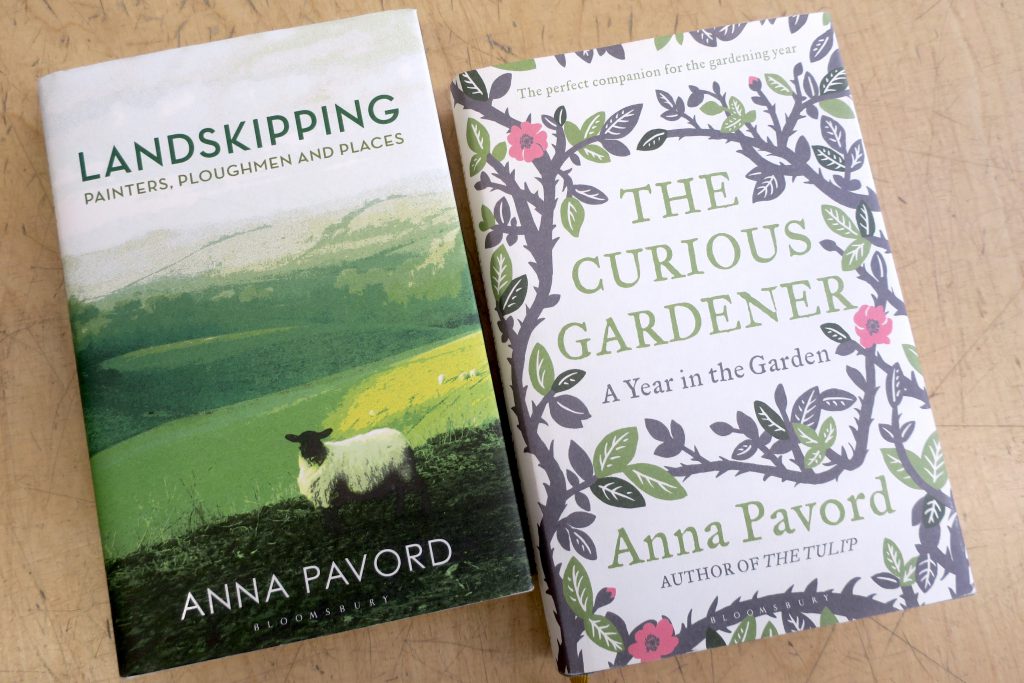

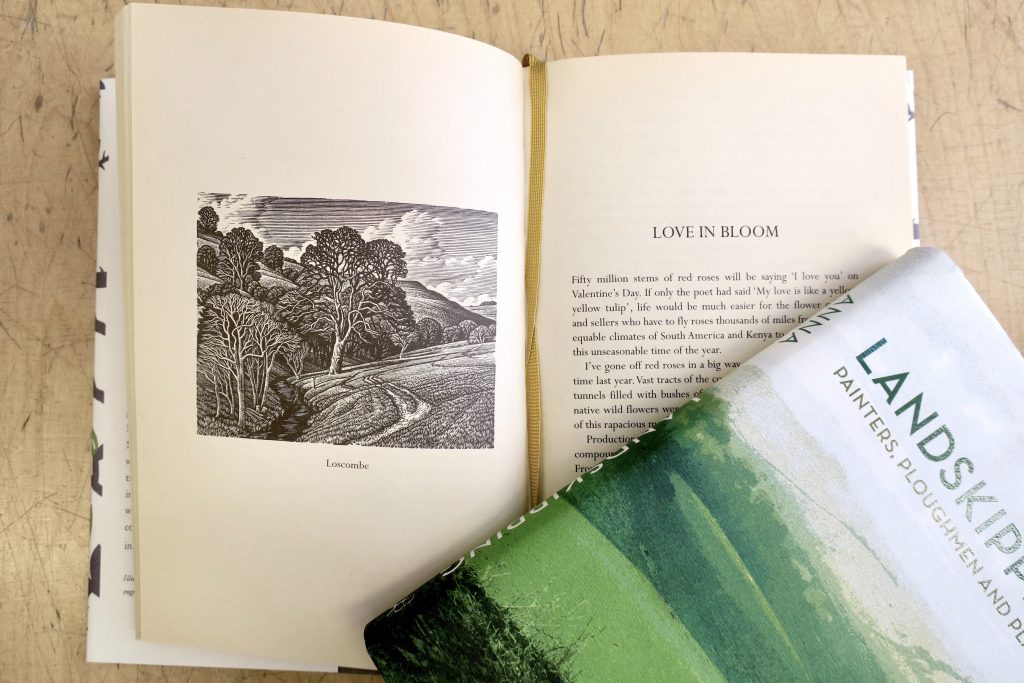

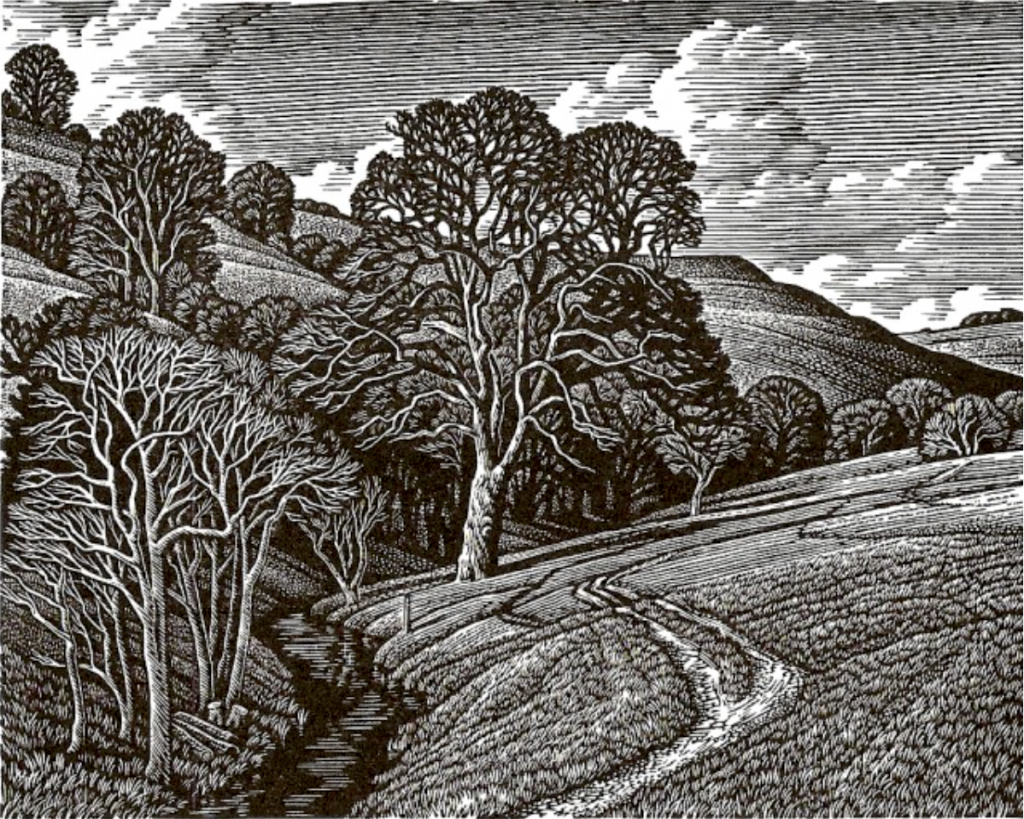

At the top of the path we joined Ridgeback Lane. Howard suggested that if we look over the gate we might see down to Loscombe from here. He had been invited by Anna Pavord to make wood engravings of the countryside thereabouts. But we were not quite high enough to see into the valley.

Loscombe

Eggardon

In Dorset tricks of history and geology have left the county unusually free of people and large towns. Or motorways to get to them. In the main, this remains a deeply rural landscape, where the burial mounds of the Bronze Age people living here in 2000 BC and the hill forts of the Iron Age people who succeeded them still remain the most dramatic features. The highest of the old camps is Lewesdon, at 915 feet, but the most powerful is surely Eggardon, with ramparts and ditches snaking round its sides in vertiginous loops. These are not natural features. They were made by men, hacking into the chalk with antler picks, and shovels made from shoulder blades. On a summer evening, the ghosts of these people, some of the earliest occupiers, lift out of the landscape, as long shadows pick out the lines of the tiny fields they made and the banked enclosures surrounding the farmhouses they built.

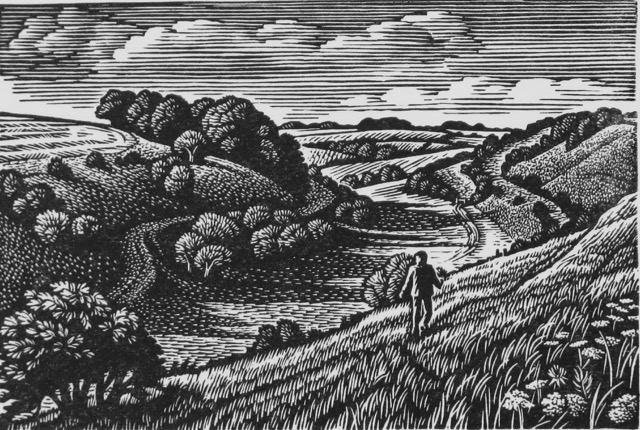

To the south we could make out a few strip lynchets, ancient field terraces cut into the hillside, reminding me of another of Howard’s engravings.

Lynchets, Combe Bissett Down

We continued along the lane, ears open for oncoming traffic, though there was none, and noses open for the scents of the hedgerows and the verges, in places filled with the pungent smell of meadowsweet in the midday sun.

At Spring Hill Farm we turned sharp right off the road into the woods, following a public footpath sign, but it was more like a stream than a path.

All woven with moss and ferns and hazel, and speckled with leaf-filtered sunshine, we splashed down through pools of water and pools of light.

There were signs for the Ant Hill Trail and I wondered if the green woodpecker I’d seen earlier knew about this path. I expect it feasted here regularly. We paused beneath a wayside ash tree and feasted on Medjool dates from Howard’s rucksack.

At the next gate a twisted pair of venerable trees, a hazel and a hawthorn, grew tangled together. A peacock butterfly rested like a brooch on the bark. Howard was drawn in, disappeared inside, looking to unravel the ancient knotted branches, gone to ground in preparation of a wood engraving.

Then over a meadow and through a green tunnel to where a bramble points out the branch of an old oak tree, all overgrown with a highlight of ferns.

A shady avenue of lime trees favoured by sheep and by cows. The sheep stepped aside to let us pass but the cows came down to see us on our way.

A mouthful of nettles.

Strip Lynchets

And then all too soon the rooftops of West Milton with Round Knoll beyond.

And just outside the village we cross another inviting holloway, a third way between our leaving and our return, but we’ll save that one for another day.

※

※

Thanks to Paul Newman for directions and to Howard Phipps for company.

One thought on “Deep Lanes & Holloways”