The top floor gallery at Annely Juda Fine Art is one of my favourite spaces and when the sun shines in through the skylight on an exhibition of sculptures by David Nash it’s just about the best place to be in all of London. Wood · Metal · Pigment continues until 7th July.

Annely Juda Fine Art is delighted to announce a solo exhibition by internationally renowned sculptor, David Nash, entitled ‘Wood, Metal, Pigment’. Large and small-scale sculptures in wood, charred wood, bronze and iron in addition to pigment works on paper, explore the breadth of Nash’s established practice with a focus on his three primary materials: wood, metal and pigment.

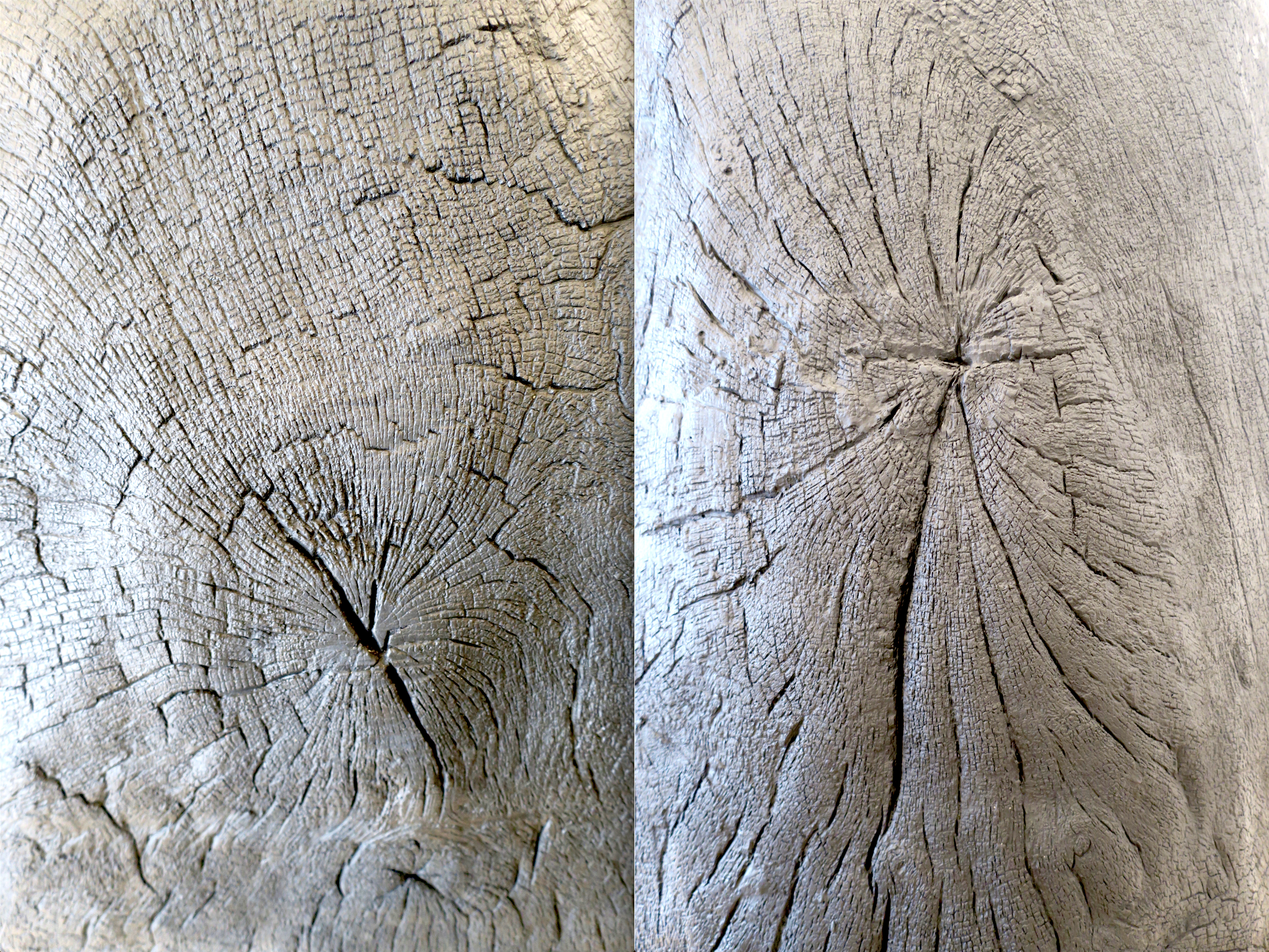

Nash has developed his sculpted work consistently over the last five decades, placing trees at the centre of his exploration. His intimate knowledge of their characteristics, both in life and in the process of change that continues after their being cut down, has informed his artistic development. Nash carefully chooses the way he treats the wood, allowing its natural qualities to inform the final shape of the work. Meanwhile, the effect of charring some of his wooden sculptures varies according to species: ‘charred beech, charred oak and charred tulip are not the same black; charred mahogany adds an evident colour to black’.

Trees are made of earth, air and water; three primary elements which David Nash often complements with fire, by charring the surface of his wooden sculptures. As Nash states, earth represents material, air represents space, water represents movement and fire represents light. Nash allows the four primary elements to inform his entire practice, whether it be in the form of wood, metal or pigment on paper.

I love these sculptures for their directness and their apparent simplicity. But then I was confused. I knew the black pieces were charred wood but I didn’t know that some of them were cast in bronze and given a black patina. It was difficult to tell them apart. Once again I found myself thinking of Sebald.

Our spread over the earth was fuelled by reducing the higher species of vegetation to charcoal, by incessantly burning whatever would burn. From the first smouldering taper to the elegant lanterns whose light reverberated around eighteenth-century courtyards and from the mild radiance of these lanterns to the unearthly glow of the sodium lamps that line the Belgian motorways, it has all been combustion. Combustion is the hidden principle behind every artefact we create. The making of a fish-hook, manufacture of a china cup, or production of a television programme, all depend on the same process of combustion. Like our bodies and like our desires, the machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers.

W G Sebald: The Rings of Saturn

If Nash’s wooden sculptures are rooted in the life cycle of a tree, his interest in metal stems from its origins and its subsequent transformation through being heated and melted. Iron, for example, is formed by one of nature’s most elemental processes and is extracted through high temperatures. Nash’s metal works explore fundamental shapes such as the cross, or expertly mimic the surface of his charred wooden sculptures, which are then cast in bronze.

Two views of Spiral, carved from a tree with a chainsaw, now cast in bronze.

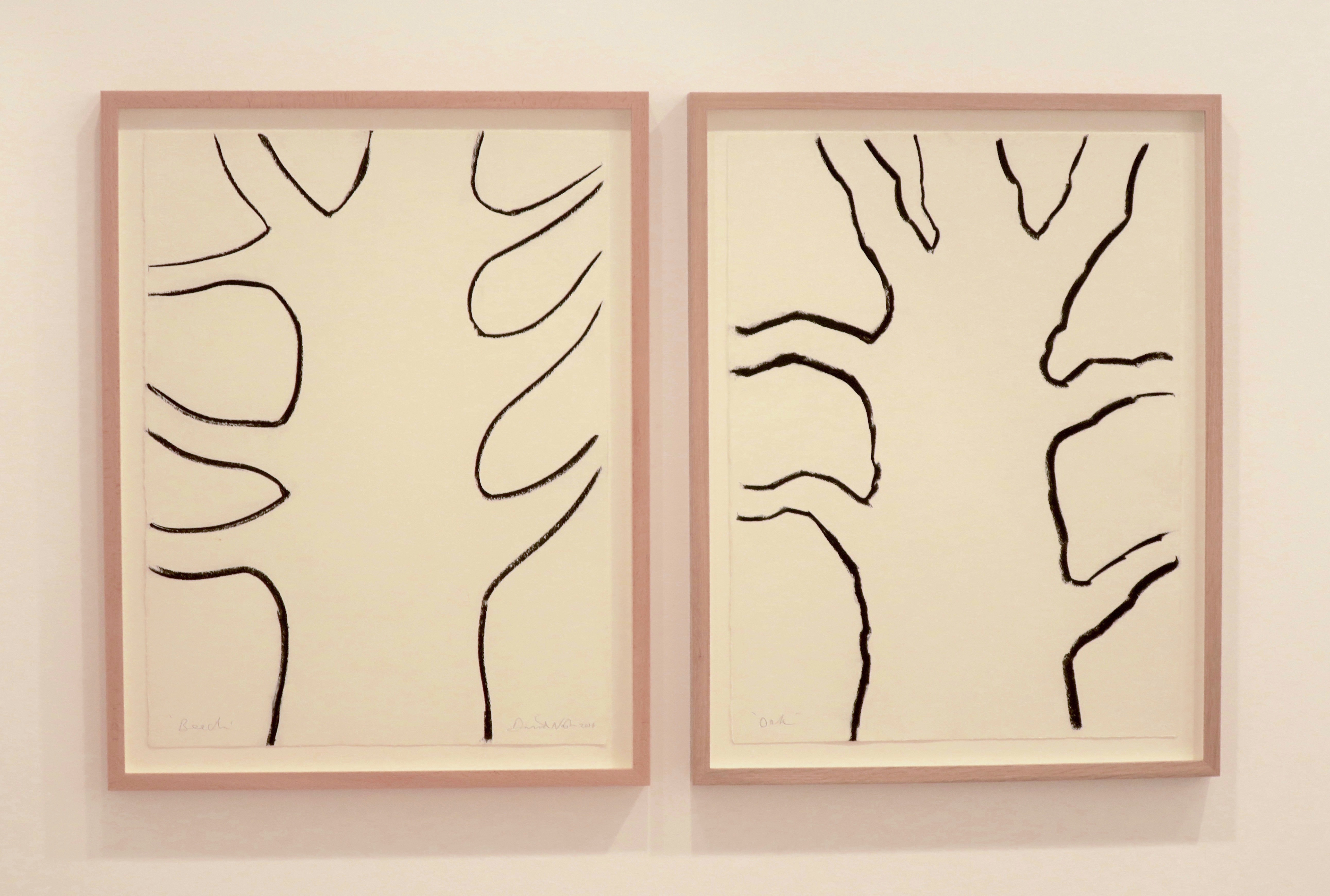

Two charcoal drawings, Beech framed in beech and Oak framed in oak.

Fire Carved Holly

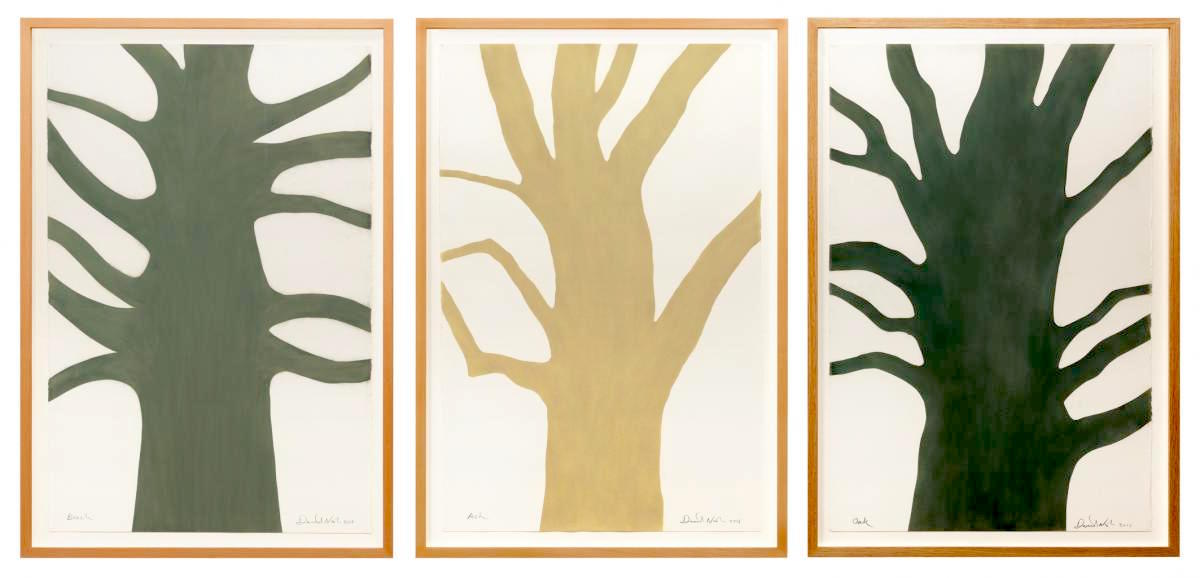

Beech, Ash, Oak

Beech framed in beech, Ash framed in ash

Ash framed in ash, Oak framed in oak

Nine Cork Oaks

Cork Dome

Red Around Black

Most woods are a variation of light to dark amber. Some species are red – Sequoia, Red Gum, Yew, Madrone and Alder. Bringing this wood together with charred wood gives me a form of colour contrast in red and black. Placed in a white walled room a third colour is present. Red, black and white are a potent triad significant in many cultures and legends. In the search for the Holy Grail there is a description of a black crow shot by an arrow lying bleeding in the snow. To explore the potential of this triad I turned to pigment on paper.

My approach to using pigment on paper is similar to my way of carving wood: being true to both the nature of the wood and the nature of the carving tool; the direction of growth and the direction of cut. I apply the pigment with a fleece pad, loading the pad with powder pigment and applying it to the paper. The paper is flat on a table so the friction of gesture inevitably spreads dust across the surface beyond the form being pressed in the paper. This dust spread can be fixed with fixative. The process requires full body and head covering, effcient masks and a powerful extractor fan. Each pigment, like each species of wood, has a different nature and quality of application. It is the same with the paper since weight and texture give different results. First I apply the colour and look for a form that the colour suggests – ‘colour form’. This is the same as starting with a ‘given’ shape of a tree or wood and finding an appropriate form.

Observation colour drawings are different from pure ‘colour form’. In May of 2016 I watched more closely the oaks coming into leaf. At first the trees have an amber ambience when the leaves are very small. As they grow that amber lightens to a yellow, then, as the chlorophyll starts to form, a light green and then to a darker green with a wax surface when the leaves are fully functioning.

I have also observed how consistent the shapes of the spaces between tree branches are according to three species of tree: Oak, Ash and Beech. This has led to a series of works on paper focusing on these dfferences. To emphasise the species’ differences, and to bring physicality to the triptychs, I have framed the drawings with the wood of each tree species.

David Nash

Oak Leaves Through May

Afterwards we walked down Bond Street and discovered it was undergoing a makeover. The road surface was being turned inside out and upside down to accommodate new infrastructure technologies hidden under the ground, while all around our ears the air hummed with the invisible threads of satellite feedback. Then amid all the hubbub of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition we found the calm sanctuary of another David Nash sculpture, Red Holed Column, a human-size totem pole of perforated sequoia standing like the analogue junction box of all our transcendental devices.

※

David Nash: Wood, Metal, Pigment