This large letter B is on a rooftop in the Born district of Barcelona. Is it B for Barcelona or is it perhaps B for Born in Barcelona (that old Springsteen classic)? Or maybe it doesn’t stand for either, especially since it’s lying on its back. Maybe it’s B for Brossa, the Catalan poet, playwright and artist Joan Brossa. He liked to play around with letters and it seems to be on the roof of his theatre. We found it when we came looking for Lottie who lives nearby. We met her under the B for Beer.

Along the way we discovered the magnificent Mercat del Born, a former public market but now restored as a cultural centre displaying the medieval archaeological ruins over which it was built.

The basilica of Santa Maria del Mar, one of the most important Gothic churches in Catalonia, and said to have the slenderest stone built columns in the world. There’s a good view of it here.

Homenatge a Picasso, a tribute to Pablo Picasso by Antoni Tàpies, an assemblage of furniture, tied with ropes, pierced with metal beams, wrapped in blankets, inscribed with – a painting is not intended to decorate a drawing room but is instead a weapon of attack and defence against the enemy – enclosed in a glass box, its sides running with water, a reminder of Fundació Antoni Tàpies from 2011.

And in the Parc de la Ciutadella there’s an elaborate cascada, there are slackliners and flocks of noisy parakeets, there’s a boating pond, a zoo and a statue waiting to catch the moon.

※

Next day we climbed to the top of Park Güell and looked down over the city to the sea. The Sagrada Família is visible left of centre. It’s somewhere we set out to visit last time we were in Barcelona, three years ago, but heat and crowds got in the way and we’ve still not made it. This was as close as we got.

Park Güell was originally intended as an up market housing estate by property developer Eusebi Güell. He asked the architect Antoni Gaudi to design ‘a grand entrance with lodges, a communal plaza, and some elaborate formal terracing, with carriage roads going up to the lots above’. But none of the lots were sold and no houses were built by Gaudi. What remains is a wonderfully fantastical garden of terraces and walkways, viaducts, colonnades and columns, and the extraordinary abstract trencadis mosaics made by Gaudi’s assistant, Josep Maria Jujol. See an earlier post here for more pictures.

There’s something about these gingerbread cottages with magic mushroom roofs that reminds me of the fantasy architecture of Portmerion, though this feels less holiday camp, more national monument.

Lottie enjoys rock climbing and the stone wall of the colonnades proved irresistible. She also enjoys swing dancing and the main plaza up above would’ve made a great dance floor for her Swing Maniacs.

There is a long and noble tradition of communal dancing in Catalonia called the sardana, a circle dance where young and old often go round together. In 2010 the Generalitat de Catalunya declared it ‘a festivity of national interest’. In the square in front of the cathedral we found twenty or more sardanes turning together like clockwork, to the sound of a band of woodwinds, brass, bass and drum.

(My favourite Barcelona band was always the hugely talented and enthusiastic musical collective known as Ojos de Brujo, now sadly no more, but if you’ve time you can catch their performance here.)

※

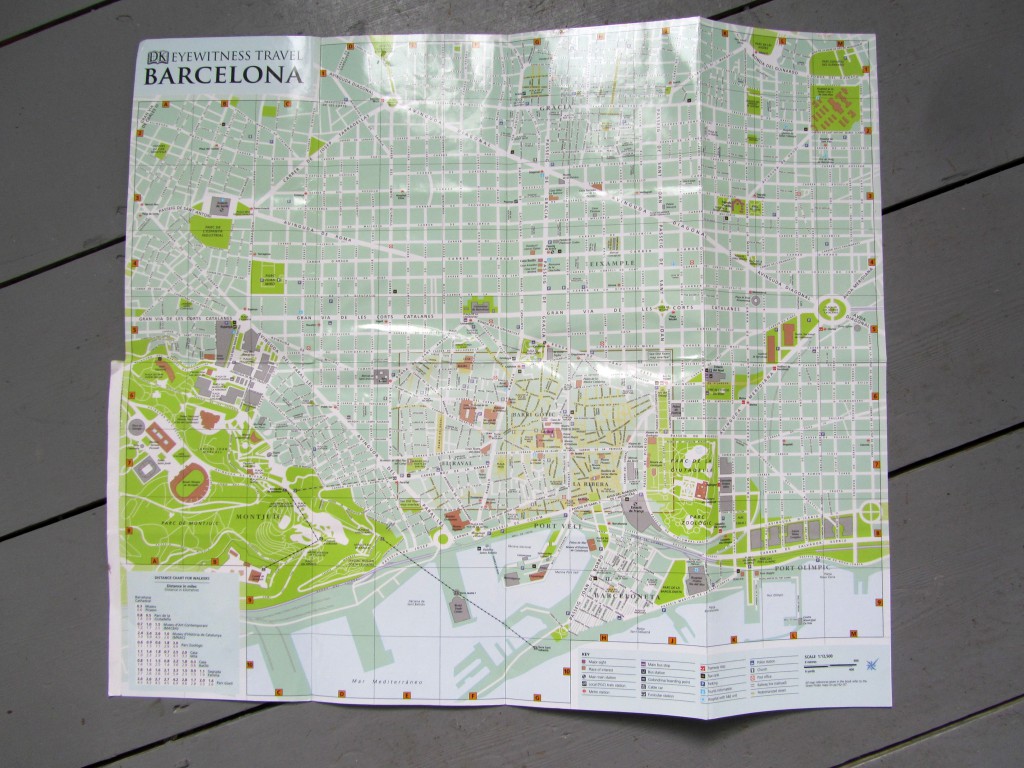

Next day we set out for Montjuïc, but first called in for a quick look at the former bullring, now transformed into Las Arenas shopping hub by Richard Rogers. It’s spectacular but there was no Camper shop so we didn’t hang about.

Up the hill, and across the street from CaixaForum and its tree sculptures by Arata Isozaki we arrived at the elegant pavilion created by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1929 for the Barcelona International Exposition. What we see is actually a reconstruction from 1986; the original was dismantled in 1930.

These are beautifully simple, well-tailored spaces. The main elements are large glazed and stone surfaces sustained by chrome faced steel columns. The walls and floor are marble – travertine, green marble and onyx – anchored to a metal structure. They form a perfect stage set for all who enter here.

In 1929, the main ceremonial buildings of the Barcelona World’s Fair decreed by the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera, such as the Palau Nacional, which now houses the Museum of Catalan Art, were pitched on or near Montjuïc – where their gross monumentality contrasted with the abstract, almost ethereal lines of Mies van der Rohe’s German pavilion, which, after its demolition, remained one of the ruling ghosts or absent classics of modernism – Robert Hughes, Barcelona.

We climbed the hill, riding the escalators to Plaça de les Cascades, but we by-passed the monstrous Palau Nacional. Strange to think it was simultaneous with the Mies van der Rohe pavilion down below. We skirted around the back, through the park, where an elderly lady fed Montjuïc’s feral cats, and discovered the quiet oasis of the Font del Gat.

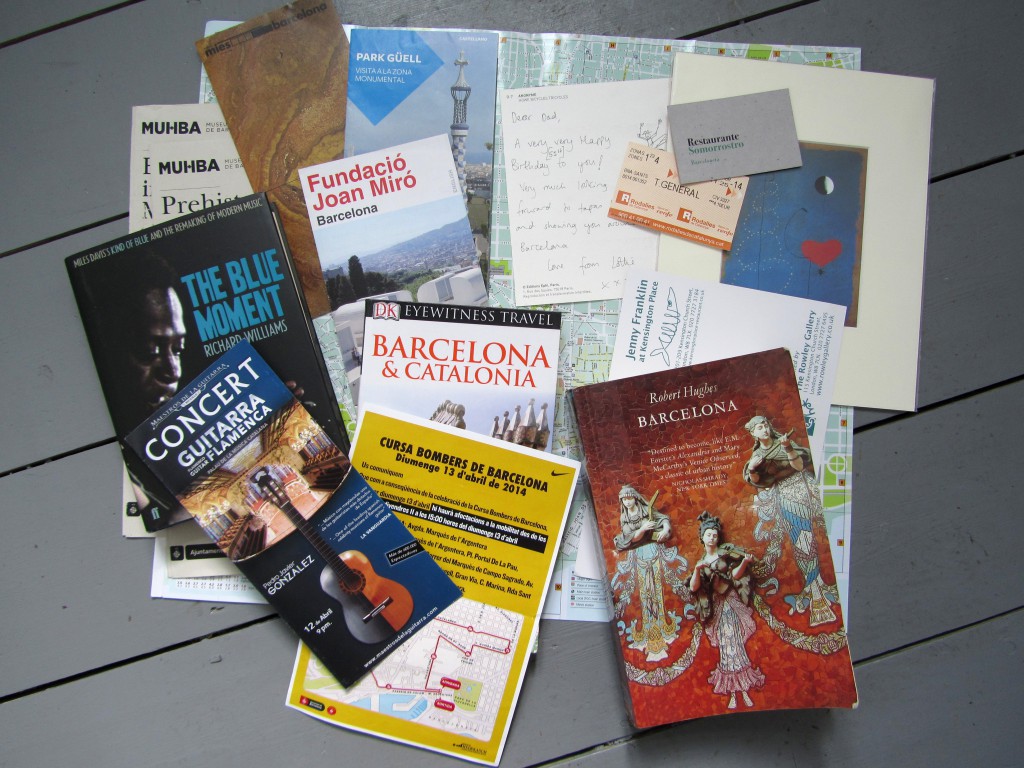

After lunch, just a little further into the park, we found our intended destination, the Fundació Joan Miró, a wonderful collection of paintings, sculptures, textiles and prints by Barcelona’s greatest artist.

There are lots of Miró’s playful, silly, colourful and uplifting works of art, perfectly displayed in Mediterranean sunshine thanks to the fantastic light-filled gallery designed by Josep Lluís Sert.

But some of my favourites were not by Miró. Down in the basement was Homage to Joan Miró, a collection of work by other artists, all friends and admirers of Miró, and donated to the museum after his death. It included this handsome concrete piece, Unorthodox Architecture I, by Eduardo Chillida.

Best of all were two rare and beautiful watercolours by Julius Bissier. I wasn’t able to photograph them and I can’t find their images online, maybe that adds to their mystique. They were an abstract mix of still life, landscape and illuminated manuscript done with a calligrapher’s touch, like a meeting of Paul Klee and Giorgio Morandi where both excelled themselves.

Back in town there’s a great ceramic mural by Chillida in Plaça dels Àngels, alongside the attractive Museum of Contemporary Art, designed by Richard Meier, but we were diverted from going inside.

Later we went to the Palau de la Música Catalana, an exuberent modernista concert hall by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, built in 1908 for the Orfeó Català choral society. The facade is rich in mosaics, stained glass, glazed tiles, sculpted reliefs and busts of Palestrina, Bach, Beethoven and Wagner.

The interior is also full of weird and wonderful detail. Lottie thought it was like being inside someone’s dream of a building. The proscenium arch is carved in pumice, with a tree on the left and winged horses on the right, like Valkyries boiling out of the clouds. On the ceiling is a huge stained glass skylight, shaped like an inverted dome, and behind the stage there are the sculpted effigies of eighteen muses, each one playing a different instrument.

…Domènech never meant the Palau to have stage sets – the building is the scenery. The hemicycle, an astonishing tour de force in ceramic, is the permanent background to the music. Its curved wall is sheathed in ‘trencadis’, or broken tiles, whose opulent shimmer is given by subtle inflections of colour running from orange through russets and a near oxblood luster to darker umbers above. Set in this hot, rich ground are the ‘spirits of music’, eighteen maidens playing eighteen different instruments, from zither to flute (the larger wind instruments, which would have unbecomingly distended their pretty cheeks, do not appear). Their lower bodies are flat with the wall and linked to one another with a swooping rhythm of garlands: lavishly patterned ‘modernista’-medieval costumes from which only their cute little feet emerge. But their heads, shoulders, and arms, along with the instruments they play, are modeled in the round and project from the wall. The effect is benignly apparitional, and without opera glasses one cannot see the broken fingers left by past ‘orfeonistes’, who were apt to hang their coats and clarinet cases on them during rehearsals – Robert Hughes, Barcelona.

We had tickets to see Pedro Javier Gonzalez perform a programme of flamenco guitar, the perfect opportunity to see the inside of this otherwise inaccessible masterpiece of Catalan architecture. We’d also been tempted by the promise of a couple of Paco de Lucía pieces, and a version of his Entre Dos Aguas turned out to be the highlight of the evening. Unfortunately a crowd-pleasing encore of Sultans of Swing left me doubting his authentic flamenco credentials, and missing Paco even more.

※

Next day we woke to find a congregation of runners buzzing outside our hotel window. They were gathering for the Cursa Bombers de Barcelona, a 10K run with all the fanfare of a full-blown marathon.

This is a very popular run in all Spain and normally it takes about a week to reach the maximum number of around 20,000 registrations. Usually around 400 firefighters from Catalonia, Andorra and other parts of Spain take part in the run. A tradition of the firemens race in Barcelona is that four firemen from Barcelona (Bomberos de Barcelona) form a relay team and each member of the team runs 2.5 km of the 10k Cursa Bombers in full fire fighting gear which weighs almost 20 kg. They compete against other firemens teams to win the coveted Firemans team prize called “Premio Especial al Bombero Equipado.”

We didn’t see any firemen running but we found one or two rock bands pumping out stirring anthems. Too much of a good thing sent us on our way to find the Museu d’Història de Barcelona in the Gothic Quarter behind the cathedral, and to my great surprise and delight we stumbled upon this beauty.

In Plaza del Rey, Topos V by Eduardo Chillida sits at the edge of the square, its three right angled steel planes confirm its corner position, its curves echo the medieval arches, it is perfectly framed.

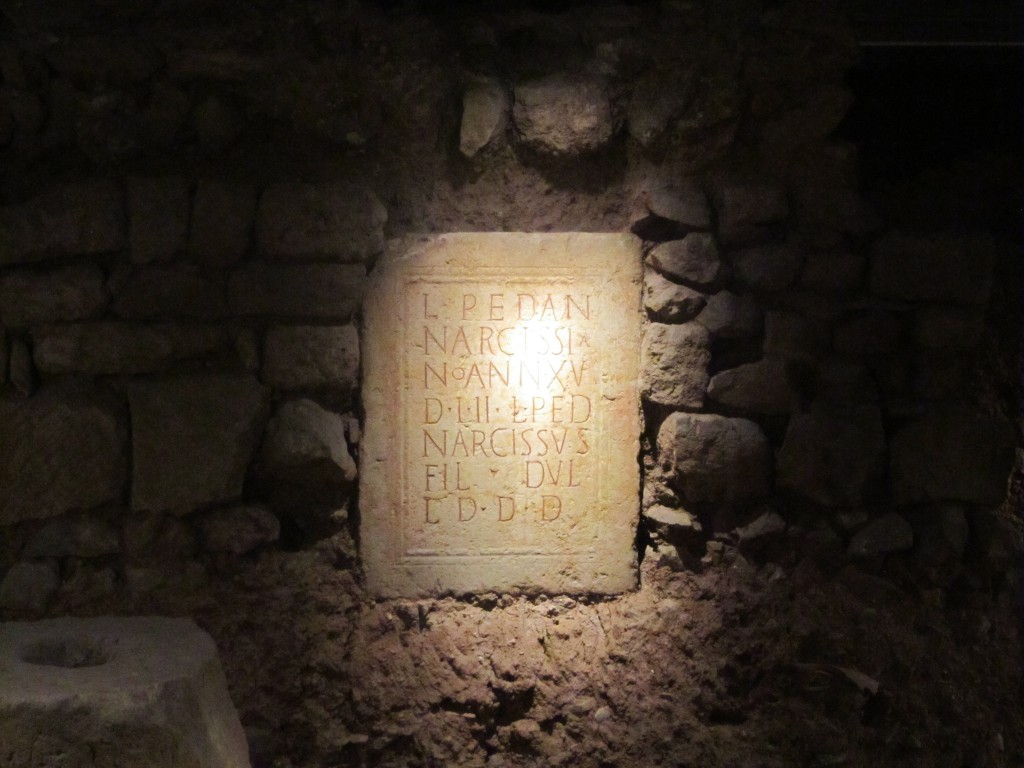

Inside the museum, we descended and wandered underneath the square, exploring subterranean streets, the meticulously excavated remains of the Roman city of Barcino. There were great clay pots wherever we looked, cauldrons, sinks and cisterns sunk into the ground, and variously described as laundries, dyeing workshops, fish salting factories and wine making vats.

We emerged into the Palau Reial Major on the other side of the square, and the Saló del Tinell and the Chapel of St Agatha. It was here in 1493 that Christopher Columbus reported his discovery of America to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

Outside again, around the back of the cathedral, we encountered the Nara Trio. There were many musicians on the streets of Barcelona, some better than others, and these were probably the best we saw. Gonzalo Abarca played soprano sax and clarinet, Mark Lupescu played kora and Leonardo Trincabelli played hang, although in this video the hang drum is played by Pedro Collares.

I was reminded of a passage by Richard Williams, from his book The Blue Moment, about the Miles Davis album Kind of Blue and its influence on modern music:

A late summer warmth is filling the streets of central Barcelona. Just off the Plaça de Catalunya, near the top of the Rambla, two young musicians are busking. One plays a metre-long didgeridoo, the ancient wooden instrument associated with Australia’s aboriginal people, a sort of rustic contra-bass pipe suitable mainly for the production of low drones. The other is playing a hang, a newly fashionable steel hand-drum that looks like two woks welded together, the smooth surface of its upper hemisphere interrupted by half a dozen large dimples. A phenomenon called the Helmholtz resonance, which exploits the sounds produced by air in a cavity, allows the hang to produce a gentle melodic ‘bong’, like a Zen monk’s version of a Trinidadian steel pan. The duo’s minimalistic music is static, almost heat-struck; it lacks obvious thematic material and seems to have no beginning or ending, no specific geographical origin or cultural inflections. A dozen listeners seem drawn more to the curious nature of the instruments than to the music itself.

A few streets away , around the corner from the Plaça de Saint-Jaume in the old quarter, a bigger group is performing in the mouth of an alleyway. This one has two hang players, plus a saxophonist whose soprano instrument has an elegantly curved neck, and a man manipulating an Indian tambura with one hand to produce a quiet background drone while playing a softly skipping rhythm on the skin of an Irish bodhrán, a single-headed drum, with the other. Their music, which has drawn a crowd of tourists of all types and ages, is similarly unaggressive. Again this is a music of resources rather than themes. Yet it has a sense of space, of balance, of containment, of refined simplicity. The absence of harmonic movement and the sound of the hang drums – their notes like heavy raindrops, splashing against the drone – invites the saxophonist to shape his improvised phrases with contemplative grace.

And I’m thinking as I walk away, the sound of the instruments fading into the early-evening hubbub, that this music could never have happened without ‘Kind of Blue’.

Further on, we came to Plaça de Sant Miquel and its towering sculpture, like an overblown doodle of twisted coat-hangers. It was only when we read the plaque on the ground that we realised its significance – Homenatge als Castellers – and it made perfect sense. It’s an homage to the Catalan tradition of building human towers or castells, recently declared by UNESCO to be amongst the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. There’s also a nice inscription below the monument by Paul Celan – Sóc més jo si tu ets més tu (I’m more if you are more of you).

We walked on, down through the Barri Gòtic, and Lottie remembered Bar Mariatchi, said to be Manu Chao’s bar, but really only somewhere he occasionally hangs out. Unfortunately, no-one seemed to know where it was, but we did find ourselves passing through Plaça de George Orwell, named after the author of Homage to Catalonia.

Also known as La Plaça Tripi – the acid square – an allusion of its reputation for civic decadence, the square throws up an interesting incongruity; it’s named in George Orwell’s honour, but for years a security camera has been mounted on the wall right next to the plaque with the writer’s name. Very Big Brother, very 1984.

We kept on walking, as far as we could go, down along the seafront with its lively Manu Chao flavoured streetbands, through Lottie’s old neighbourhood of Barceloneta and down onto the beach.

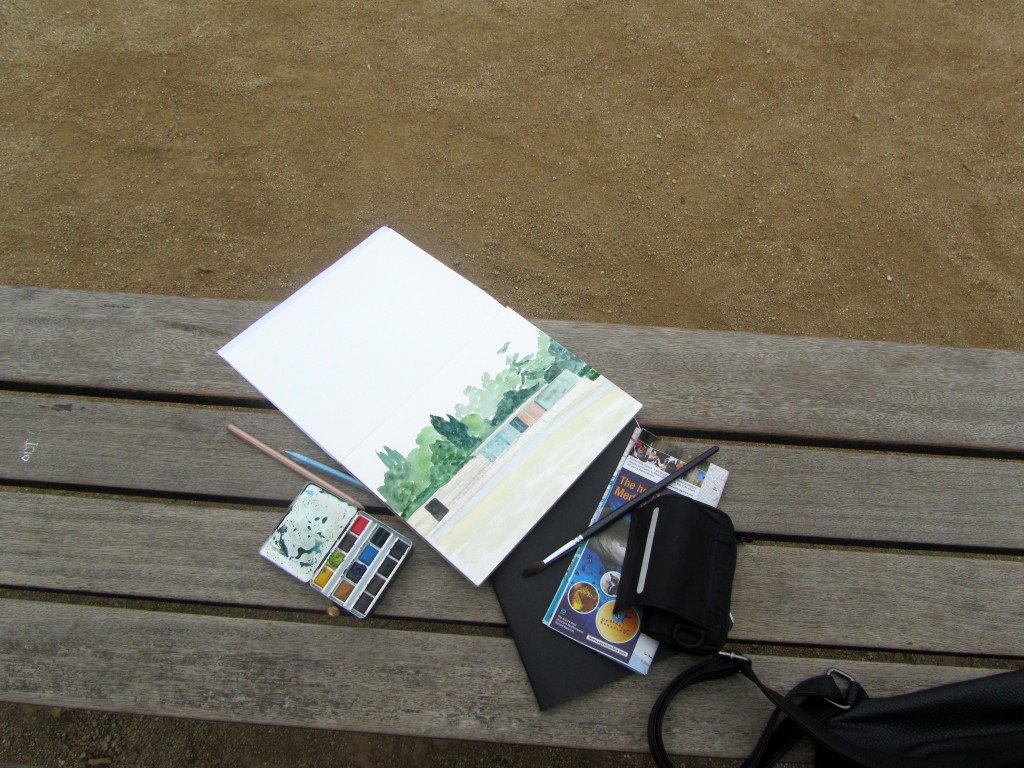

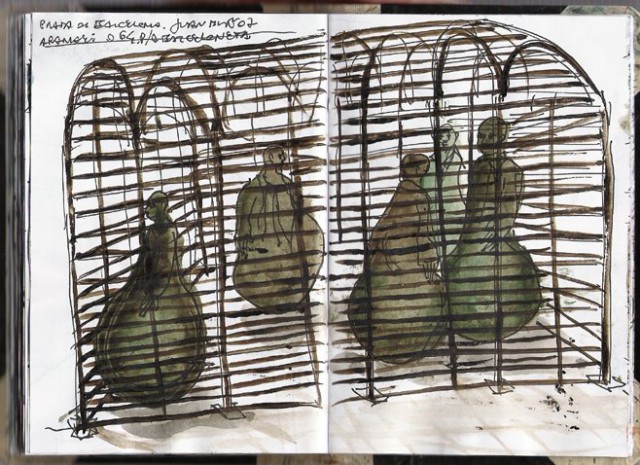

At the southern end, in Plaça del Mar we found a surprising desert oasis, a shady grove of trees around a small shelter, or perhaps it’s a cage. It’s known as Una habitació on sempre plou (A room where it always rains) and it’s the work of the sculptor Juan Muñoz.

This third image is courtesy of Eduardo Salavisa, from his splendid blog – desenhador do quotidiano.

Just up the road from here we ate our best meal at Somorrostro, a fantastic local seafood restaurant with an international gourmet reputation. It was recommended to us by Meri, a native of Barceloneta now working at Kensington Place restaurant in London, and coincidentally it’s just around the corner from where Lottie lived when she first moved to Barcelona.

Afterwards we did a little nighttime sightseeing…

…and we bid farewell to Chillida’s bold and beautiful metal box, branded B for Barcelona.

What a fabulous and comprehensive guided tour of Barcelona. Thanks very much.

I agree. It’s a fun place. Thanks for taking us along.