At the gate we met a man with a camera, overloaded with telephoto lenses, overexposed to the sun, returning to the shelter of his car. He’d taken up photography in retirement, pursuing butterflies over the Downs, but today there were too many people and too few photo opportunities. He’d seen Green Hairstreaks and Orange-tips but didn’t think he had any good photos. As we spoke, bright yellow Brimstones danced around his head, but too quick to photograph. “It’s the story of my life,” he said.

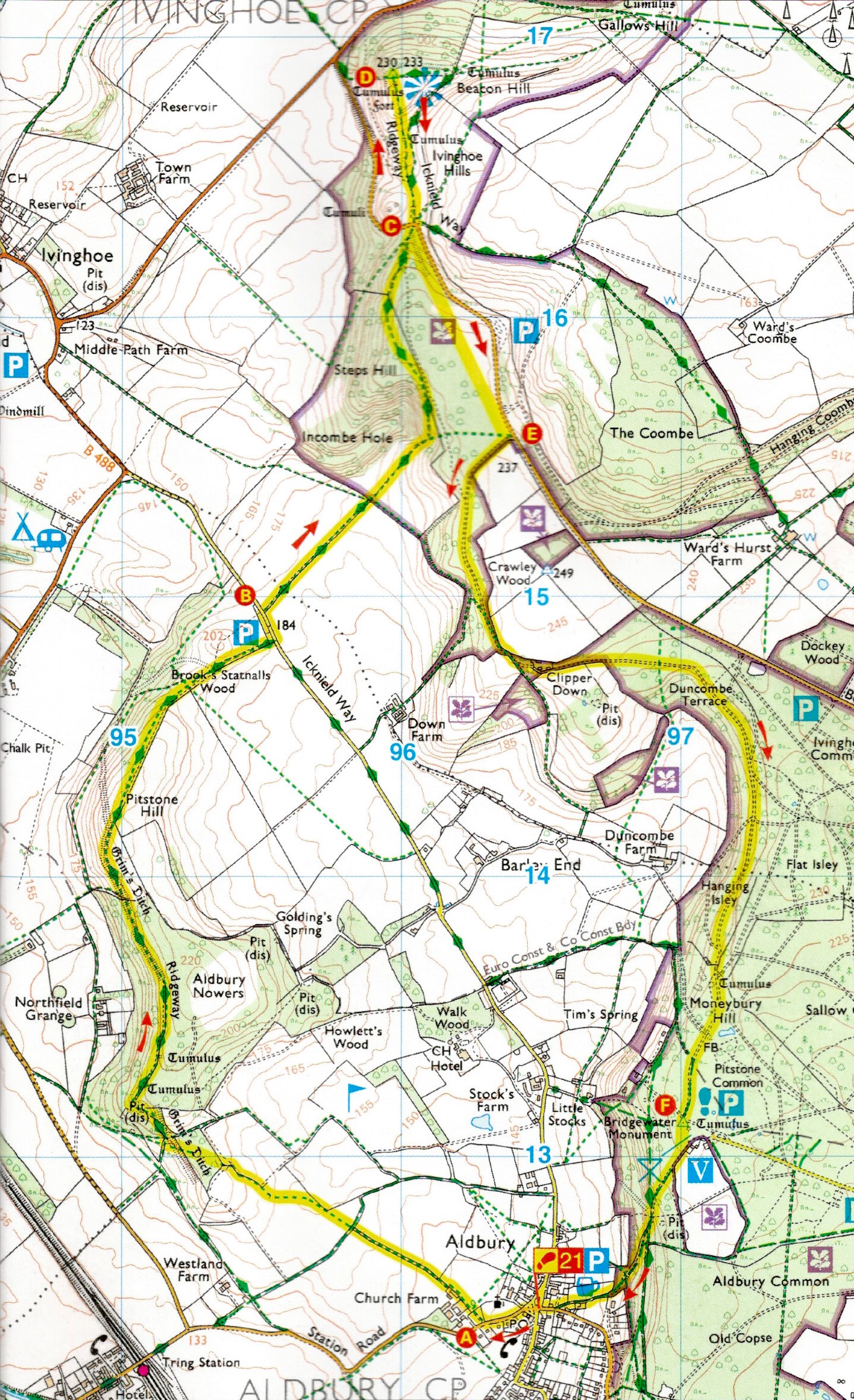

We had joined the Ridgeway at its junction with the Icknield Way, heading for Ivinghoe Beacon. It was Palm Sunday, a week before Easter, and the hottest day of the year so far. As we came around Incombe Hole, other walkers on the far side climbed the penitential route up the face of Steps Hill.

The approach to Beacon Hill led us over the two smaller Ivinghoe Hills. From here it’s just possible to make out the White Lion carved into the chalk hillside below Whipsnade Zoo, and Dunstable Downs beyond, where we’d earlier had breakfast beneath a blue sky full of gliders and kites and butterflies.

Ivinghoe Beacon is the northernmost terminus of the Ridgeway, an ancient track said to be Britain’s oldest road. From here it stretches south-west to Overton Hill near Avebury, along the line of the Chilterns and Wessex Downs. The mile and a half we’d just walked is shared with the Icknield Way.

It wasn’t until last night that I reached Ivinghoe Beacon, whose great chalk summit is crowned by an Iron Age hill-fort. I scrambled up to one of its grassed-up ramparts, sat facing westwards and let the setting sun soak me with its warmth. I took off my shoes and socks. My feet were puffy as rising dough. Across the land, millions of bindweed flowers completed their final revolutions of the day, buttercups returned their last lustre to the sun, the wallabies of Whipsnade settled to sleep and the day slowed to its close.

Sitting there in that buttery sunshine the many different names of the path – Yken, Ychen, Ycken, Ayken, Iceni, Icening, Ickneld, Ikeneld, Ikenild, Icleton, Ickleton, Icknield – seemed to melt and combine, such that the Way seemed not like a two-dimensional track but part of a greater manifold, looping and weaving in time even as it appeared to run singularly onwards in space. ‘I could not find a beginning or an end of the Icknield Way…’

Robert Macfarlane: The Old Ways

Turning to retrace our steps, we were met with the view that Paul Nash must have seen in 1929 when he made preparatory sketches for his painting of this resonant place. As we came down off the hill, I zigzagged either side of the path looking for his exact viewpoint, but the closer we got the more the image disappeared. The Ivinghoe Hills behind the beech trees sunk below the horizon, making me think that perhaps he’d witnessed the scene from Beacon Hill through binoculars, in the same way he’d seen Wittenham Clumps from Boar’s Hill – Landscape – Paul Nash – Wittenham Clumps.

Paul Nash, Wood on the Downs, 1930

We walked through the Wood on the Downs, beech hangers along the ridge above The Coombe, the land falling away steeply to the east. Here we turned west into Crawley Wood, where a fallen tree prompted a Nash inspired black and white photograph.

Beyond Crawley Wood the path climbs to Clipper Down through a holloway bordered by wild garlic and caves formed by the roots of fallen trees. A wild boy jumped out of one of them, right in front of us like a startled dryad, then ran on to catch his parents. Sunlight glistened on newborn leaves and birdsong echoed through the branches.

From Duncombe Terrace we were accompanied by a procession of hikers, an Anglo-Asian walking club from Luton, chatting excitedly all down the steep wide path through Hanging Isley, where the great, tall, slender beech trees watched us pass by. Their shadows traced new tracks on the ground.

At Moneybury Hill, beneath the trees stands a well defined Bronze Age barrow mound with a surrounding ditch. It is fenced off but there is an entrance gate. A family were picnicking on the summit so instead I photographed this beautiful dancing oak tree growing nearby. Its branches seem to unwind like the ribbons of a maypole. The woods hereabouts can become very busy due to the proximity of the car park at the Bridgewater Monument, where a spiral staircase inside the column rises up above the treetops. There is also a café, a children’s playground and a National Trust shop.

A little further and there’s a lovely view through the trees down to Aldbury, a cluster of rooftops and a church tower, a cosy bucolic scene reminiscent of an etching by Robin Tanner.

We followed the path steeply downhill, descending through the dappled light of a wooded holloway, to emerge below the woods into the village of Aldbury. Only then did we realise we’d been here before.

Over the years we’ve done many walks around the Chilterns and it seems that all paths must lead to Aldbury, and just like before we had lunch once again at the Greyhound Inn by the village pond. It has all the appearance of a timeless, quintessential English village, sleepy and conservative and somehow inescapable. Patti Smith would love it. I read recently that on her visits to London she likes nothing better than to check into a “small favoured hotel” and watch endless reruns of Midsomer Murders, often filmed in Aldbury. So Patti, next time you visit, come and walk with us through Midsomer Land.

After lunch we walked behind the church, following the public footpath signs, down beside Church Farm and over the golf course towards Grim’s Ditch.

The first mention of Grim’s Ditch was a grant of 1170–90 in the Missenden Cartulary referring to it as Grimesdic. The Anglo Saxons commonly named features of unexplained or mysterious origin Grim. The word derives from the Norse word grimr meaning devil and a nickname for Odin or Wodin the God of War and Magic.

At the place of the blank signpost we consulted the map.

A tree kindly provides a handrail to guide us around the corner.

We followed the stepping path up into Aldbury Nowers, an area of magnificent tree shadows and

one of the best sites in the country to see butterflies, although so far we’d noticed only Brimstones.

I stepped off the track to photograph a fallen tree, one of many shallow rooted in the chalk soil. As I turned back, two figures were approaching, a couple together, both female but one more masculine, short-haired and dressed in dark clothes with heavy walking boots, her partner barefoot in a multi-coloured, floaty dress with long blonde hair, the prettiest butterfly we’d seen all day.

Root & Branch

We left the woods and came up over Pitstone Hill, the air was filled with the song of the skylark, the horizon was the route we had taken. Down below were chalk pit pools with bone-white beaches and sun-bathing picnickers. In the distance we spied Pitstone Windmill and further afield in the Vale of Aylesbury, a single wind turbine. And beyond where we began was the headland of Ivinghoe Beacon.

A line made by walking.

※

Paul Nash in Pictures: Wood on the Downs / Ashridge Estate / The Ridgeway

Lots of lovely tree shadows.

Yes indeed, a rich entanglement of shadows and light.