The approach to Lincoln was long and flat with wide vistas of huge arable fields, along straight roads accompanied by oversized tractors, through countryside reminiscent of the industrial-scale farms of northern France. But lest we should forget where we were, on the outskirts of the city a little old lady stood on the pavement nodding involuntarily at the passing traffic, waving a St George’s Cross with the word England written across it. A radicalised ukipper standing her ground against the waves of migrant workers come to steal her crops… But then we saw the cathedral.

In these dark days of deception and misinformation when so many are convinced of self-harm and the reckless destruction of our country, to be cast adrift off the coast of Europe for no good reason, when to be English is to be stupid and an international embarrassment, then there’s some consolation here.

It was the Autumn half-term and we’d come for a long weekend in the middle of nowhere to a place we’d never been before. Or so we thought, until it became the middle of somewhere we’d already seen.

The cathedral felt somehow familiar, like a dream of a cathedral, the richness and intricacy of the details combined with the visual tangle of the pillars and the arches, it was a forest carved in stone, an ideal of Englishness that recalled a primordial time before the first woodland clearances.

I have always held… that the cathedral of Lincoln is out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British Isles and roughly speaking worth any two other cathedrals we have.

John Ruskin

A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture. Nearly everything that encloses space on a scale sufficient for a human being to move in is a building; the term architecture applies only to buildings designed with a view to aesthetic appeal…

Lincoln Cathedral is as English as Amiens Cathedral is French and Florence Cathedral, Italian. This is what we must again have, if we believe that a healthy European life cannot exist in uniformity and regimentation. Should international planning impose an international idiom, nearly all the visual pleasure would go out of the new buildings.

Nikolaus Pevsner

A Brief History

After his conquest of England, William the Conqueror embarked upon a programme of cathedral building throughout the country. In 1072 William instructed Bishop Remigius to move the seat of his diocese from Dorchester on Thames to Lincoln. The diocese stretched from the Humber in the north, to the Thames in the south.

Building a cathedral required a huge workforce of skilled craftsmen and labourers who worked from sunrise to sunset. It is estimated that £2,000 a year was spent on building the Cathedral; nearly £5,000,000 in today’s money.

In 1185 the Cathedral was partly destroyed by an earthquake, leaving only the Norman west front which you can still see today.

In 1186, Hugh of Avalon accepted the post of Bishop of Lincoln and began to organise the rebuilding of the Cathedral. Work began in 1192 at the east end and continued until around 1245 when it joined the existing west front. The restoration is said to have been paid for by local people, including famously, the Swineherd of Stow who gave his meagre life savings towards the great work. His statue sits on the northwest turret opposite that of Saint Hugh on the southwest.

Much of the design and construction of the Cathedral was experimental and in 1237 the central tower collapsed. It was replaced by 1311 with a tower topped with a spire making the Cathedral approximately 525 feet high (160m) and reputedly the tallest building in the world for nearly 238 years. In 1548 the central spire fell down in a storm and had to be removed. It was never replaced.

The Russell Chantry, seen here on the left, where Duncan Grant painted murals in 1959 depicting Christ the shepherd among his flock. The sheep are being sheared and fleeced, and their bundles of wool loaded aboard a cargo ship at Brayford Pool on the River Witham below the Cathedral.

And the light of the south streams in through the window.

In the forest of stone.

At the shrine of St Hugh.

The east window is the largest 13th century window in the world.

Evidence: Jon Groom

I remembered an old exhibition catalogue I’d picked up years ago at Notting Hill Books, The Journey: A Search for the Role of Contemporary Art in Religious and Spiritual Life, and I saw that five paintings on copper had been hung beneath this great window in 1990 as part of The Journey, an exhibition installed around the city featuring the work of Roger Ackling, Craigie Aitchison, Stephen Cox, Richard Devereux, Jennifer Durrant, Garry Fabian Miller, Jon Groom, Sue Hilder, Eileen Lawrence, Richard Long, Leonard McComb, Glen Onwin, Peter Randall-Page and Keir Smith.

Four years later I had received this small piece of Evidence,

a token of Lincoln Cathedral still waiting to be discovered.

We returned to the crossing, under the Bishop’s Eye rose window, where in 1990

Richard Long’s Halifax Circle had also been installed as part of The Journey.

We came along the slype corridor to the cloister and the magnificent chapter house, where an elegant performance was underway to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the Charter of the Forest. It was a spectacular event, worthy of a chapter to itself, so I’ll save that for the next blogpost – Log Book.

The Cloud of Unknowing

The Table of the Spirit

Lincoln Cathedral stands on top of a steep hill and is a commanding presence overlooking the surrounding landscape. We descended and found our way to the Usher Gallery and the Collection.

Tide: Stuart Haygarth

mixed media, 2012

‘Tide’ is a chandelier made from colourless plastic artefacts found along the coastline of the UK, during a five hundred mile walk by the artist. The form of the chandelier refers to the moon as a light source… The moon is central to the concept… The moon controls the tides and causes the plastic to wash ashore…

Poppies in a Green Bowl: Ivon Hitchens

oil on canvas, c.1947

Hitchens was committed to colour and a loose open style of brushwork. He often painted directly in front of the subject as in this domestic work, as well as en plein air (outside). Hitchens was taught by Clausen… at the Royal Academy schools. Both artists were influenced by the bold use of colour of the French artists of the time and this particular work was said to be influenced by Matisse’s interiors.

Zinnias: Vanessa Bell

oil, 1943

Vanessa Bell was a painter, interior designer and illustrator. She is the sister of writer Virginia Woolf and illustrated covers for her books, most famously ‘The Lighthouse’. A key figure in the Bloomsbury group Bell held the first meeting of that collection of artists and thinkers in her townhouse and was instrumental in founding the Omega workshop, an artist co-operative for decorative arts. Bell later moved to Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex and continued to mix fine and decorative arts. The house contains many murals and decorated pieces of furniture in the same style as this painting.

Lincoln from the South with Bargate: Peter DeWint

oil on canvas, 1824

This painting clearly demonstrates DeWint’s technical mastery of oil paint. DeWint preferred southerly or easterly views of Lincoln Cathedral as these have a stronger silhouette. The now demolished medieval Bargate with its rural activity forms the main subject. The contrast of the crisp textures in the foreground to the atmospheric rendering of the Cathedral is well handled. The painting shows the rural proximity to the city. Bargate was in Lincoln’s southern suburb of Wigford a mile and a half from the Cathedral.

Cow Creamers

These creamers originated in the Netherlands in the early 18th Century, and were made in this country from the mid part of that century onwards. Milk or cream was poured into the jug through an opening in the back of the cow, with a stopper being inserted to keep out the dust. The mouth served as the spout whilst the cow’s tail was the handle. They vary considerably in material and decoration, but the ones on display here are earthenware and all were produced in Staffordshire factories. The decoration ranges from sponged underglaze and overglaze to a lustred finish. Often cows are accompanied by a suckling calf or are modelled with a milkmaid. Although still being produced today, there were some health issues with the use of these creamers as they were difficult to wash out properly, and gave rise to salmonella poisoning in some instances.

The figure of a cow with a boy and a dog is Prattware, most probably from Yorkshire. Prattware is cream tinted earthenware, and was originally produced at the Pratt Factory in Staffordshire, but the name was later applied to the type of ware and produced in various factories across the UK.

The Brayford Pool and Lincoln Cathedral: John Wilson Carmichael

oil on canvas, 1858

After a period at sea and an apprenticeship to a shipbuilder, Carmichael became a pupil of the elder TM Richardson. From 1838 to 1862 he sent oil paintings and watercolours for exhibition at the Royal Academy and in 1845 moved to London, later settled in Scarborough. (This painting is) a colourful and relaxed depiction of how commercial life on the Brayford once was. Perhaps slightly idealised with images of fishermen and swans. The detailed rigging in the fishing boats and their straight masts draw the eye right up to the Cathedral, which is gently absorbed, into the sky.

across the sky: Edmund de Waal

wall-mounted vitrine

(wooden interior and aluminium frame glazed with low reflective glass)

holding 5 thrown porcelain vessels in celadon glazes, 2013

Edmund de Waal is a nationally acclaimed potter and author. He spent some of his childhood in Lincoln and was inspired by ceramics he saw in the collection of the Usher Gallery to want to start making his own. In ‘across the sky’, there are a few grey-blue, sky-blue, sky-grey celadon vessels which sit in close proximity in a vitrine.

Lincoln Cathedral, Exchequergate and Castle Square: William Logsdail

oil on canvas, c.1904

In 1904… Logsdail decided to attempt to paint a series of pictures of the Cathedrals of England. He began in his home town… (but this) was to be the first and last of Logsdail’s intended series…

Lincoln Cathedral and Exchequer Gate from Castle Square

The Glory Hole, Lincoln: Edward John Niemann

oil on canvas, 1860

Edmund John Niemann’s ‘The Glory Hole, Lincoln’ records the run-down timber-framed houses along the banks of the Witham navigation canal.

The River Witham and the Glory Hole

The Wool Staple in Medieval Lincoln: Duncan Grant

oil on wood, 1957

This painting is a sketch for the mural housed within the Russell Chantry in Lincoln Cathedral. The work sits on the west wall and depicts a fictionalised Lincoln from the Brayford – the same view as the Carmichael painting (see above). The painting includes members of Grant’s family, his partner Vanessa Bell and daughter Angelica Garnett can be seen in the grouping of women on the left.

Brayford Pool and Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln: Laurence Stephen Lowry

oil on canvas, 1959

This work was commissioned by Sir Geoffrey De Freitas, MP for Lincoln. He invited Lowry to visit Lincoln, and Lowry wished to paint the industrial buildings down by the River Witham. Lowry was reluctant to paint the Cathedral as it features in so many paintings of Lincoln, but he did include it eventually.

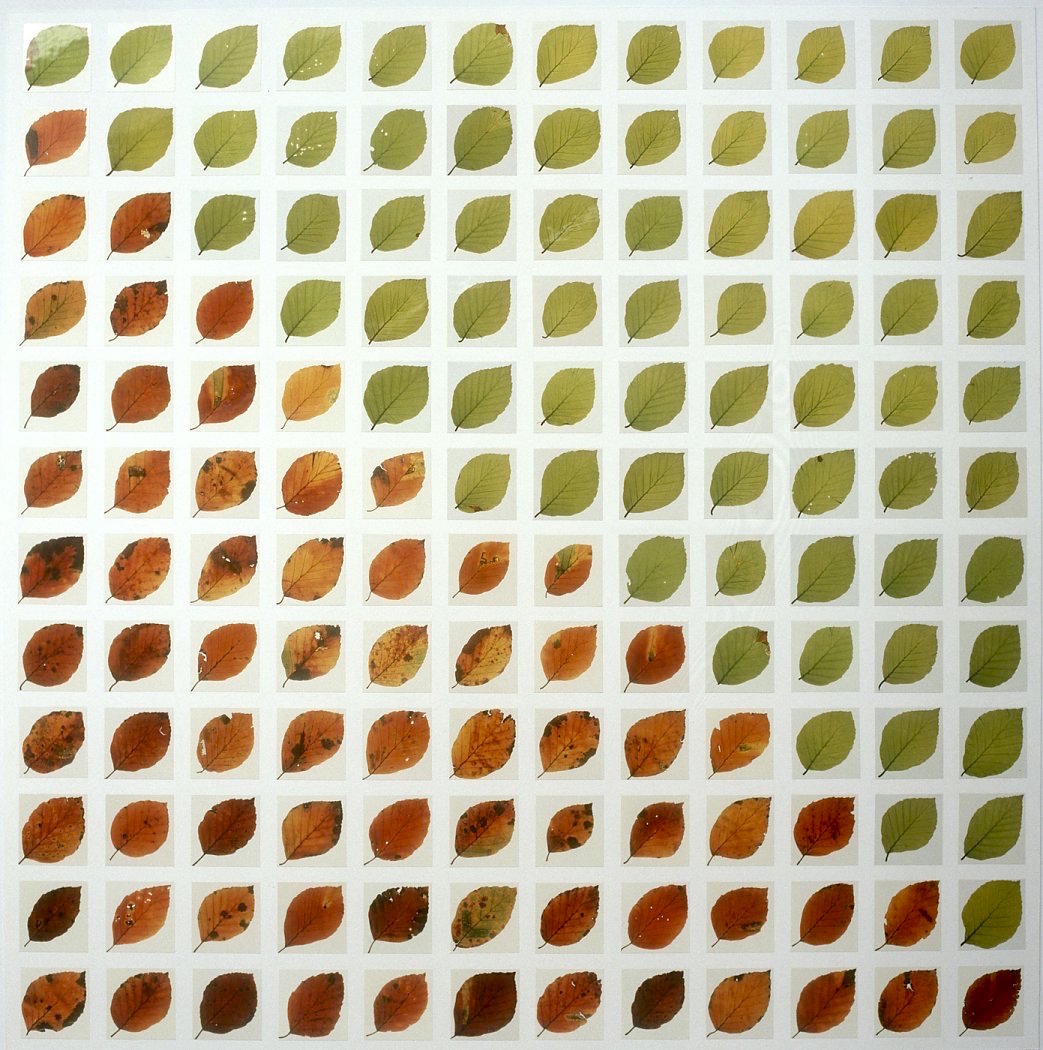

With the Beech, toward the Healing: Garry Fabian Miller

light and leaves, 1986

This photographic work is made (without a camera) from leaves gathered from a beech tree which once grew in the Usher grounds and from a number of beech trees around Lincolnshire. The leaves collected are from autumn and spring and show the sharp contrast between the colours of these two seasons. The leaves were collected from various sites both public and private creating an alternative map of Lincolnshire.

Autumn Rings Andeuze, September 1971 – Spring 1983: Terry Frost

acrylic on canvas, 1983

After discovering acrylic paint while teaching in California in the 1960s, Frost became increasingly interested in colour as a presence or character in itself. Frost made many works incorporating discs and spirals which evoke the sun. Commenting on a trip to the desert, which inspired many spiral works, ‘I found the desert not as I believed it to be… Arizona was full of cacti in bloom, with spirals of colour everywhere’.

Rock ‘n’ Hole: Richard Wilson

1 metal and glass cabinet containing 4 metal shelving units holding a collection of stone cores, 2005

Using a technique from the construction industry, an industrial coring machine… was used to remove cylinders of stone material collected from the local area of Lincolnshire. The cores reveal the structure of the ground beneath the surface… in an almost forensic manner…

The Charms of Lincolnshire: Grayson Perry

tea-towel, 2006

This printed tea-towel is a multiple (unlimited edition) designed and made for sale alongside his exhibition The Charms of Lincolnshire at the Victoria Miro Gallery, London, 2006 (first shown at The Collection, the new museum of art and archaeology in Lincolnshire). For this show Perry selected historic artefacts – everything from toys, costume and bibles to game-keepers’ traps, coffin plates and a wooden hearse, from various museums of rural life and social history in Lincolnshire. These were shown in conjunction with his own works – including dolls, vases, plates, and an embroidered sampler, all of which were designed to blend together in what was described as “a three-dimensional narrative poem” exploring death, childhood, religion, folk art, hunting and the feminine (a theme of particular interest to Perry, who is a transvestite). Many of the objects in the exhibition are depicted in the image on the tea-towel, with Lincoln Cathedral in the background and with various phallic fungi prominent in the foreground. The title of the exhibition evokes a bucolic cliché of National Trust England; Perry chose to design a tea-towel as a reference to the ubiquitous souvenir tea-towels found in every NT and country-house gift shop.

After purchasing a souvenir tea-towel we headed back for a last look around the cathedral precincts.

Illumaphonium – an interactive music making sculpture

Between Two Worlds: Michael Dan Archer

sandstone, 1998

Between Two Worlds: White Van Driver

mixed media, 2017

※

In memory of Olivia Thomson, 1935-2015

Olivia sent me this postcard over twenty years ago. It was my first conscious sight of Lincoln Cathedral, the first time I ever took notice and thought this was a place I should visit. So when after all these years I finally got here, I felt her watching over my shoulder. And there was consolation here.

What a great post about a magnificent building Chris. The quality of the carvings is superb, thank you for sharing the photo’s. I popped in to Manchester cathedral this week to offer up a little prayer. Best wishes Joe.

Thanks Joe. Those carvings are like prayers in stone.

Chris, I love Between Two Worlds: White Van Driver

mixed media, 2017. Very clever!

Hank