One of the deciding factors for a holiday on Lake Como this year was its proximity to Lake Maggiore and the small lakeside town of Ascona, where the municipal museum holds a collection of abstract miniatures by Julius Bissier. A rare opportunity to see a group of his beautiful paintings all together. Or so we thought. But first a quick promenade.

The middle of Via Moscia is just the place for a discreet phone call from your Wiesmann Roadster.

Word of Ascona began to spread a century or more ago, when a slow but steady influx began of philosophers, theosophists and spiritualists, most of whom believed that a return to nature was the best remedy for the moral disintegration of Western society. At the turn of the twentieth century the artists Henri Oedenkoven and Ida Hofmann established an esoteric, vegetarian artists’ colony on the hill of Monte Verità beside Ascona. An array of European fringe intellectuals followed: in 1913 Rudolf van Laban set up his nudist School of Natural and Expressive Dance within the Monte Verità community, attracting Isadora Duncan among others. During and after World War I artists and pacifists flocked to Ascona. The buildings atop the peaceful wooded hill are now mostly used for conferences, but a few have been preserved as a museum of the movement.

Ascona’s tour de force is Piazza Motta, the cobbled lakefront promenade, south-facing and fully 500m long: its airy views down the lake, flanked by wooded peaks, to the Brissago islands are sensational. There are few better places to watch the day drift by: the morning mists on the water, the clarity of light at midday, the sunsets and peaceful twilight are simply mesmerizing.

Ascona’s attractive cobbled lanes leading back from the lakefront are full of artisans’ galleries, jewellers and craft shops. The Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna, in a sixteenth-century palazzo, has a high-quality collection focused on Marianne von Werefkin, one of the artists attracted to Ascona in its heyday and joint founder of Munich’s expressionist Blaue Reiter movement. – The Rough Guide to The Italian Lakes

The Piazza Motta is flanked along its other side by a parade of attractive restaurants with al fresco dining, which is where we consoled ourselves with a glass of wine and a risotto Milanese after a disappointing visit to the municipal museum, where Bissier’s paintings were nowhere to be found.

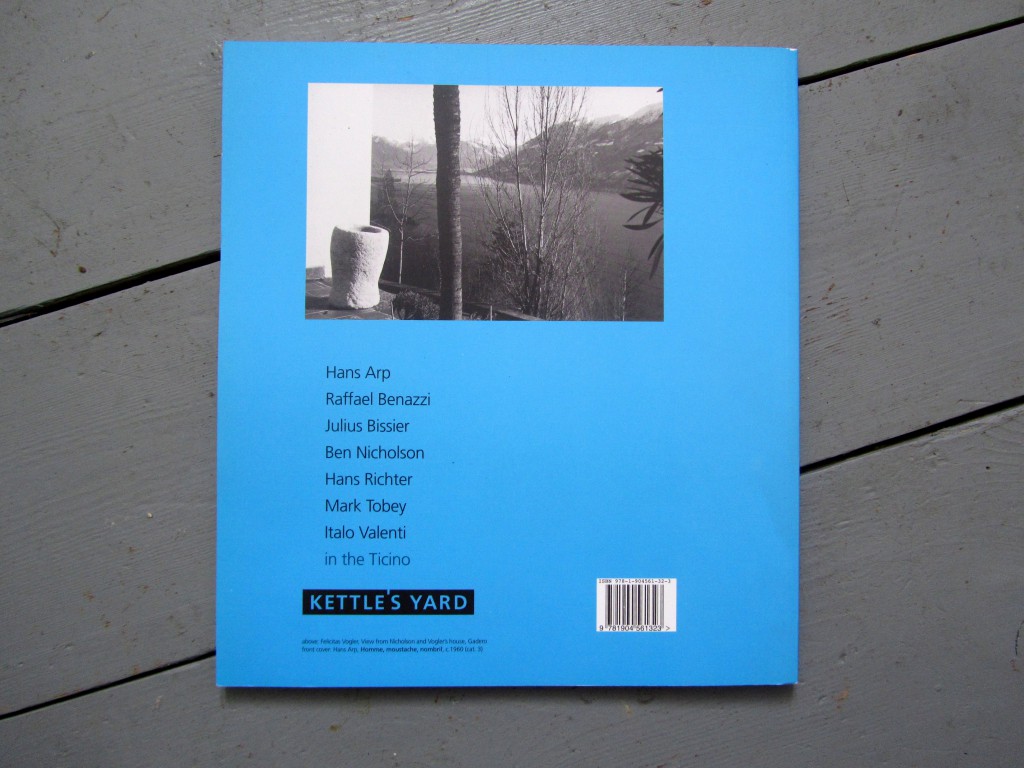

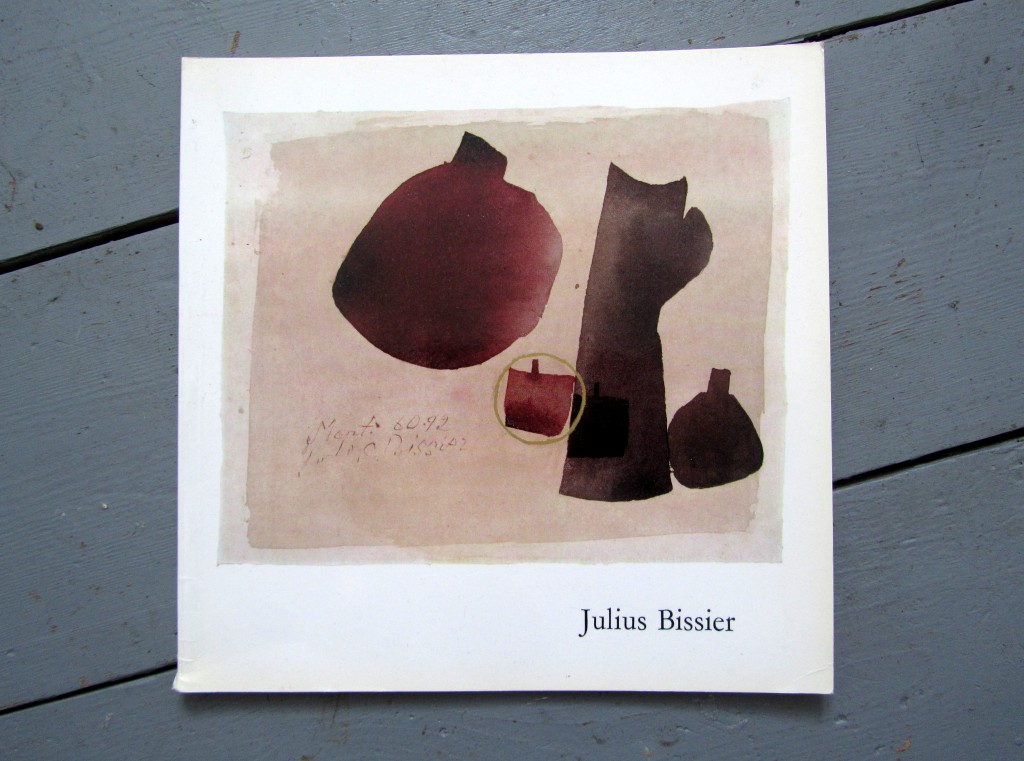

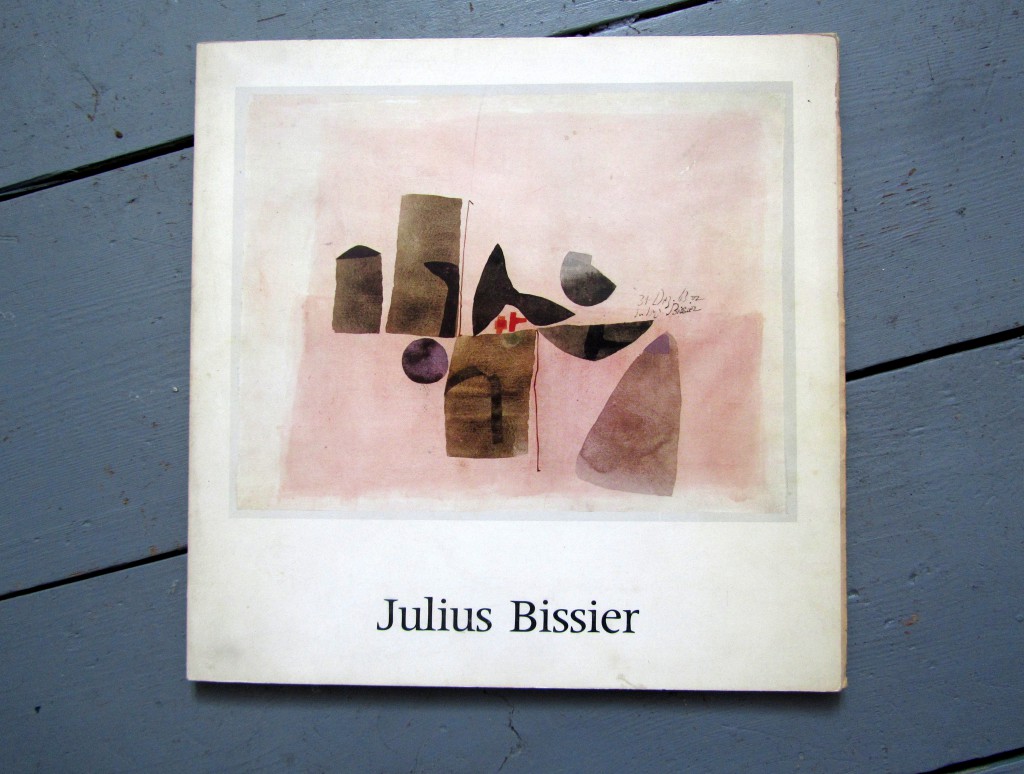

This was the museum when we passed by after lunch, closed between noon and 3pm. We’d earlier been inside and found only paintings by Marianne Werefkin on one floor and a different artist on another floor, I can’t remember who, I hardly stopped to look, it was all bright, gaudy expressionism but I only had eyes for the refined and contemplative miniatures of Julius Bissier. All I found was a postcard and a catalogue for an exhibition I’d seen five years earlier at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge.

The image on the cover is not by Julius Bissier; this is Homme, Moustache, Nombril by Hans Arp. The exhibition was a homage to Ascona and the Ticino in the late 1950s and early 60s where a remarkable group of artists settled, described by Bissier as ‘the roundhouse of international spirits’.

It inspired me to come looking for more of his elusive paintings. I knew his work from earlier catalogues found in second-hand bookshops and more lately I’d been startled by two of his beautiful paintings in the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona.

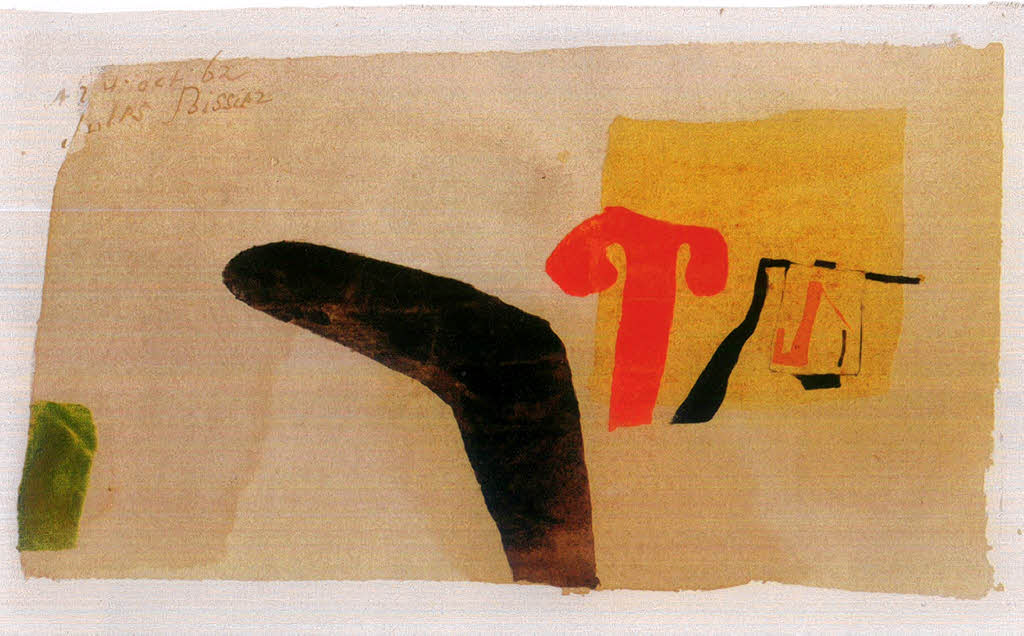

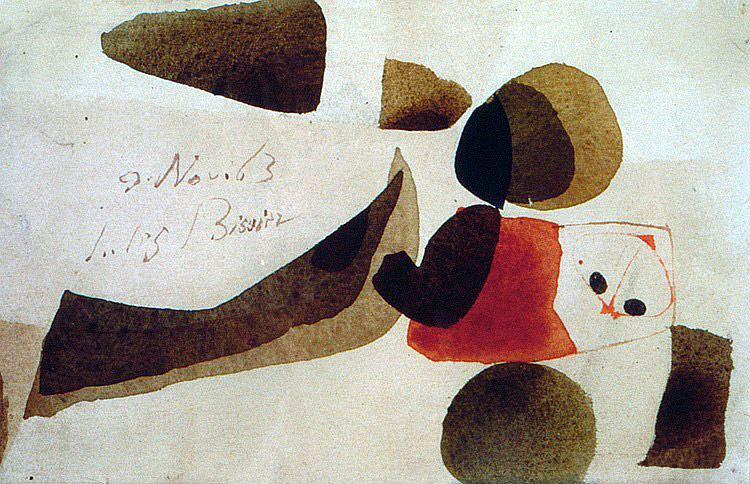

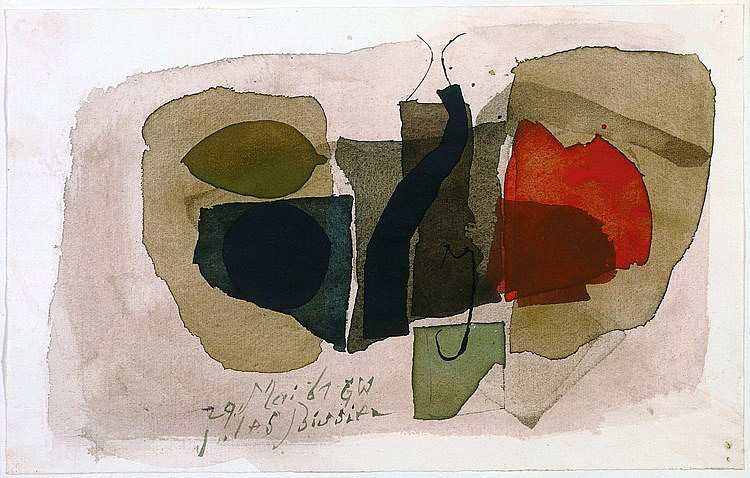

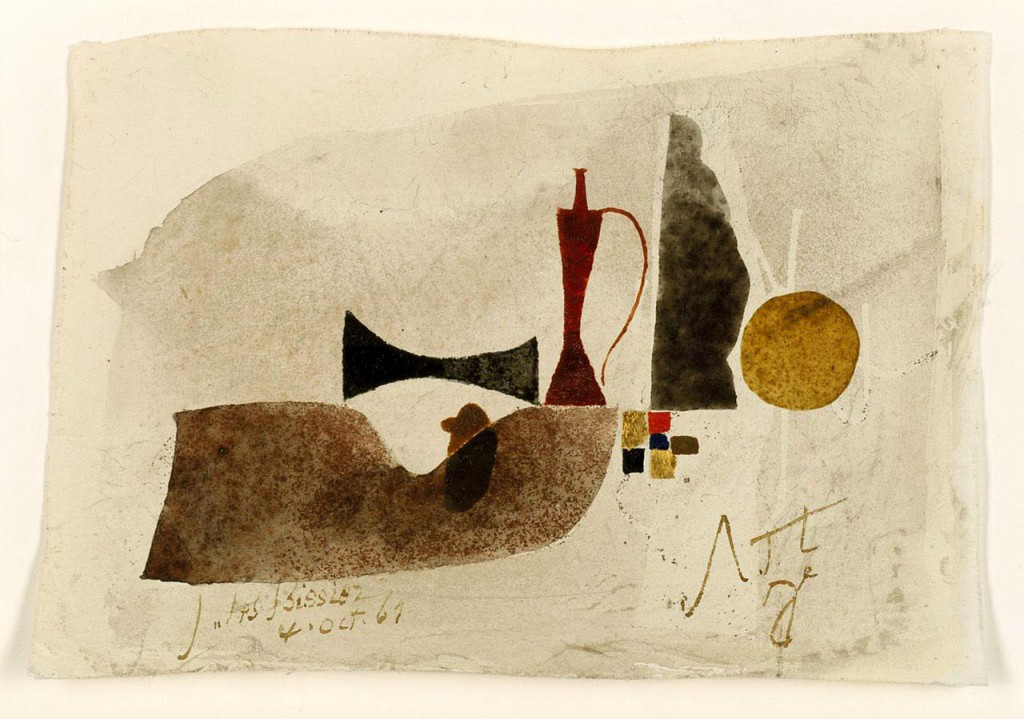

But there were none to be found in Ascona. The treasures of the Collezione Comune di Ascona and the Archivio Julius Bissier were not on public display. So here are some beauties I found on the internet.

Julius Bissier was descended from a French family. He was born in Freiburg near the Black Forest in Germany in 1893. His early figurative paintings in the 1920s attracted praise and were considered promising, part of the Neue Sachlichkeit, but when he lost his university teaching post at the beginning of the Hitler regime he retreated into obscurity.

In 1939 he and his wife moved to a village on the shore of Lake Constance, where he secretly continued working but never exhibiting his paintings. He was overlooked until the 1950s when he was rediscovered by Werner Schmalenbach, a perceptive museum director who gave Bissier a major retrospective exhibition in 1958.

From that date until his death not many years later, Bissier was recognized, even beloved. Advanced in age and confirmed in his taste for privacy, Bissier did not become a public figure, but his work – enchanting, light of touch, easily accessible yet profound – made its way around the world. – An Art of Our Own: The Spiritual in Twentieth Century Art, Roger Lipsey.

His art, as it had already evolved unnoticed some two decades ago, now flowed unexpectedly into the mainstream of contemporary art. Nevertheless, we must remember that Bissier, born in 1893, belonged to an earlier generation. Bissier, who only at the age of forty developed his own personal style and only at 56 gained a reputation, belonged to the generation of the ‘pioneers’ of modern art.

He belonged to those who expected from art that it make some statement about the nature of the world, of being, of the cosmos and the universe. Klee’s saying, that art should not render the visible but render the invisible visible, is aimed at this ‘great unknown’, which was a general concern of the artists of his generation. Baumeister entitled his ideological book: ‘The Unknown in Art’. As one of the first of that generation, Kandinsky spoke of ‘The Spiritual in Art’.

Although the ecstatic tone of Expressionism was not part of this cosmic reference, it continued to be decisive in art; for Klee just as for Schlemmer, for Mondrian as for Bissier. Bissier’s friends among the great painters of the time all belonged to the same ‘classic’ generation and shared the same preoccupation with ‘The Spiritual in Art’: Schlemmer and Baumeister, Hans Arp, Ben Nicholson and Mark Tobey. – Werner Schmalenbach, catalogue introduction, Julius Bissier 1893-1965.

Bissier’s late miniatures, from 1956 until 1965, were painted either in watercolour on paper or egg-oil tempera on irregularly shaped, unstretched canvas. They have their roots in calligraphy, with elements of still life and mosaic and maybe sometimes specimens from a microscope’s slide.

Bissier’s signs in the miniatures seem innumerable: simple geometric figures, bottles, vases, and cups, letters of the Roman and Greek alphabets, little bright blocks resembling mosaic, patches of goldleaf, seeds, stones, colored planes defining areas and coloured washes defining atmospheres, abstract brushwork imported from his earlier work, vaguely animate forms that might be snails or wings, abstract shapes that have no name.

He gathered all of these protagonists in the world of his new art in loose but not careless compositions, as if they had been turning in a kaleidoscope and briefly configured to please the artist. There is no trace here of strenuous “composition”, no Golden Section or other stern device; on the contrary, there is utter relaxation, as if an infinitely sensitive but undemanding awareness had allowed this to happen. – An Art of Our Own: The Spiritual in Twentieth Century Art, Roger Lipsey.

Recognition came late, but vehemently; the exhibition presented in 1958 by Werner Schmalenbach at the Hanover Kestner Society made Julius Bissier world famous in one fell swoop. It was followed by contributions to Documenta and biennales, international museum exhibitions and awards. Just one year before the Bissiers had travelled for the first time to the Ticino, to the mountain village of Ronco. From then on they visited every year until the final move to Ascona in 1961. For the painter, who had lived so long in oppressive isolation and solitude, the possibility of friendly exchange was surely an important argument in favour of the move to the Ticino, which had been a meeting place for international intellectuals since the days of Monte Verità. Hans Arp, whom the painter had already met in 1955 and whom he held in high regard, lived in Solduno. Bissier soon also became friends with Italo Valenti, Ben Nicholson, Raffael Benazzi and Remo Rossi, all of whom lived nearby. Friends from outside the area, such as the writer Erhart Kästner, also liked to visit. In addition to all this was the grandiose landscape around Lake Maggiore, as much Alpine as Mediterranean, offering a mild climate that was not least a health benefit to the painter.

Here were the southern light, soft and diffused through mist over the lake (Bissier called it the “‘heavenly light’ of the Ticino”), the granite rocks with their rich hues from silver-grey to golden-brown, the mountains and their mirror-image on the surface of the lake, material and immaterial reality almost indistinguishable. All these rang with the unmistakable clusters of the Ticino church bells – their relation to the spaces depicted in the miniatures is not to be overlooked. Monti, Ronco, Brione, Madonna della Fontana – the familiar names of the places that he loved to seek out and where he also painted, as well as, of course, again and again his home, ‘Rondine’ – were often carried over to the miniatures. In this way Bissier turned exterior things into an interiority, and at the same time transformed the personal into the universal, the present moment into timelessness. In all earnest, this was the most deeply exhilarating aspect of his art.

In the last four years of Bissier’s life in the Ticino, ink brush drawings and miniatures were made in abundance. Meanwhile, he went for many walks, sought out the places he loved in and around Ascona, took photographs, listened to music and played the cello, met for conversation with friends and read a lot (Heraclitus, the medieval mystics, Zen and Taoism and, again and again, Bachofen). Here he could live and work in retreat, but also companionably when he needed to. A painter-hermit of the 20th century, a great master of Western modernity: one can safely assume that Julius Bissier, at the end of his life in the Ticino, had truly arrived.

– Matthias Bärmann,

Vineyard house, granite house: places of retreat and of friendship – Julius Bissier and Italo Valenti in the Ticino, Mark Tobey on the road, ‘the roundhouse of international spirits’.

It was such a shame to find that these magical paintings, their poised brushstrokes like distillations of the Ticino landscape, like wildflowers, are locked away and hidden from view. They deserve to be seen in the land where they grew, Julius Bissier’s home for his final four years and his most fruitful.

A great essay Chris and beautiful photographs.

I liked seeing Julius Bissier’s work, really fine paintings,

Thank you

Thanks Chris. I love his delicate tempera paintings on scraps of canvas, but they’re difficult to find.

Bissier is a new name for me. Lovely work and Ascona looks fabulous.