Three walks in Epping Forest, all within the past few weeks. This time of year I can’t get enough of its green light to escape the city. I never lived in a forest but this place always feels like home. Maybe I did in a previous life, maybe we all did, maybe this is the nearest thing to a prelapsarian London.

27 May 2019

The hollow oak by Warren Pond is a good place to start.

Barn Hoppitt is an ancient pollard wood and many of its veteran trees even outdate nearby Queen Elizabeth’s Hunting Lodge which is over 470 years old.

Barn Hoppitt, across Ranger’s Road from Queen Elizabeth’s Hunting Lodge, is the best example of oak wood-pasture in the Forest, with well-spaced ancient oak pollards over sparse grassland with many anthills and a mosaic of scrub patches.

A lone fisherman on Warren Pond

Yellow flags

Epping extends to the northeast of London, and it is very far from a wildwood. It was first designated as a royal hunting forest in the twelfth century by Henry II, with penalties for poaching that included imprisonment and mutilation. Presently it is managed by the City of London Corporation, and has more than fifty bylaws governing behavior within its bounds — though the punishments are now fiscal rather than corporal. It is fully contained within the M25, the orbital motorway that encircles outer London. Minor roads traverse it, and it is never more than two and a half miles wide. Despite its small extent, Epping is easy to get lost in — a forest of forking paths to which, for a thousand years, the people of London and its surrounds have gone for shelter, sex, escape, and a relic greenwood magic.

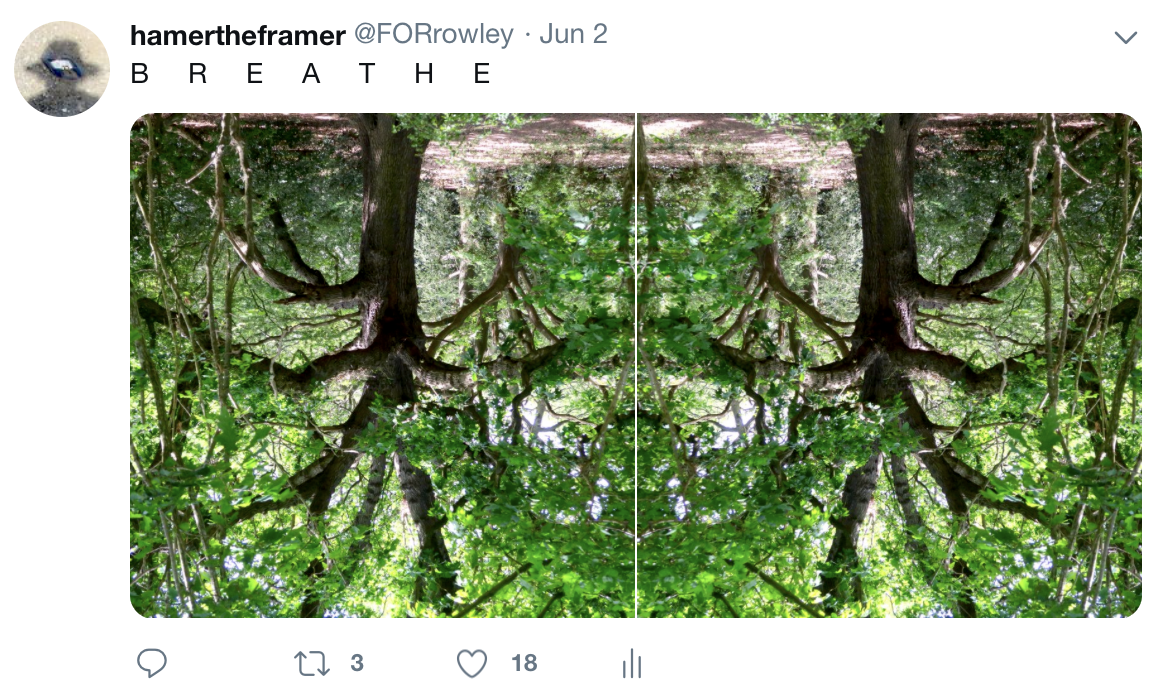

From Warren Pond we descend to deeper green woodland, tangled and lush and always disorienting, we’re suddenly submerged in a dream of wilderness, wrapped and rapt, above, below and all around.

Shadows of branches plot routes of roots

Next time you walk through a forest look down. A city lies under your feet. This is a line from Anne Tsing, quoted in Robert Macfarlane’s most recent book, Underland, in which he spends a good deal of time in Epping Forest, thinking about what’s beneath it, so don’t be surprised if I dig up a few quotes.

Occasionally – once or twice in a lifetime if you are lucky – you encounter an idea so powerful in its implications that it unsettles the ground you walk on…

In the early 1990s a young Canadian forest ecologist called Suzanne Simard, studying the understorey of logged temperate forests in northwest British Columbia, observed a curious correlation. When paper birch saplings were weeded out from clear-cut and reseeded plantations, their disappearance coincided with first the deterioration and then premature deaths of the planted Douglas fir saplings among which they grew…

It seemed to her plausible that the paper birches were somehow helping rather than hindering the firs: when they were removed, the health of the firs suffered. If this interspecies aid-giving did exist between trees, though, what was its nature – and how could individual trees extend help to one another across the spaces of the forest?

Simard decided to investigate the puzzle. Her first task was to establish some kind of structural basis for possible connections between the trees. Using microscopic and genetic tools, she and her colleagues peeled back the forest floor and peered below the understorey, into the “black box” of the soil – a notoriously challenging realm of study for biologists. What they saw down there were the pale, superfine threads known as “hyphae” that fungi send out through the soil. These hyphae interconnected to create a network of astonishing complexity and extent…

Simard’s inquiries confirmed that beneath her forest floor there did indeed exist what she called an “underground social network,” a “bustling community of mycorrhizal fungal species” that linked sapling to sapling. She also discovered that the hyphae made connections between species: joining not only paper birch to paper birch and Douglas fir to Douglas fir, but also fir to birch and far beyond – forming a non-hierarchical network between numerous kinds of plants…

The fungi and the trees had “forged their duality into a oneness, thereby making a forest,” wrote Simard in a bold summary of her findings. Instead of seeing trees as individual agents competing for resources, she proposed the forest as a “cooperative system,” in which trees “talk” to one another, producing a collaborative intelligence she described as “forest wisdom.” Some older trees even “nurture” smaller trees that they recognize as their “kin,” acting as “mothers.” Seen in the light of Simard’s research, the whole vision of a forest ecology shimmered and shifted – from a fierce free market to something more like a community with a socialist system of resource redistribution…

Then all of a sudden a frantic rustling over our heads…

I stopped and looked up to see a stream of squirrels leaping from tree to tree, playful young acrobats chasing each other through the branches. At 00:44 they all come together in a treetop squirrel-train.

And just about here, by the fallen tuning fork, we slipped off the main path into a parallel world.

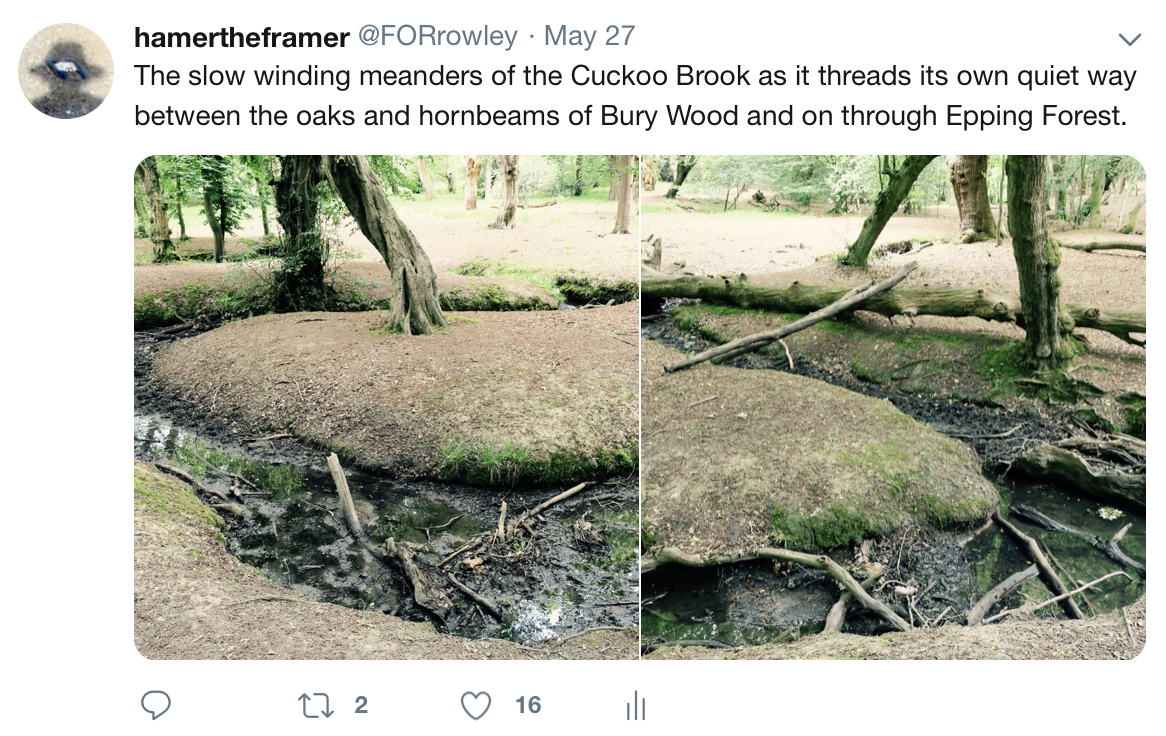

This ditch is marked on the forest map as The Ching, the river that flows from Connaught Water down to Highams Park Lake, and on the way gives its name to nearby Chingford. But without a map it’s the I Ching and these logs an auspicious hexagram, one of the 64 changes of the ways through the forest.

We emerged beside a nameless tree, twisting and plaited and disguised as holly.

And another hidden dancing oak.

The forest stays with you when you leave, its patterns enter your dreams, you retrace your crooked path while you sleep, and by morning you’ve built a tangled night-shelter from its fallen branches.

The inside becomes the outside, and as above then so below; we’re enwrapped in an intricate system of mutual correspondences, and we’re the grit that becomes the pearl or we’re the spanner in the works, or just maybe we’re the missing link that promotes everlasting life and an eternal Christmas…

But somehow I don’t think so.

Hornbeams in Bury Wood

Funfair on Chingford Plain

Queen Elizabeth’s Hunting Lodge on Dannet’s Hill

Longhorn cattle browse the common grazing areas of the forest, their range controlled by invisible fencing. They wear special collars that react with an underground cable laid around their enclosure. Within six metres they get a buzz and within one metre they get a shock, so they quickly learn to turn back when they get the buzz. No more cattle grids. It’s another aspect of the Epping Forest underland.

※

2 June 2019

That first walk was on Bank Holiday Monday. Six days later we returned and began a second walk where the previous one had ended. This time there were six of us and I’d made a mental map to share all my favourite spots in the forest. It turned out to be a bit of a stretch, probably our longest Epping Forest walk to date. Just as well we’d started out with a hearty breakfast at Butler’s Retreat.

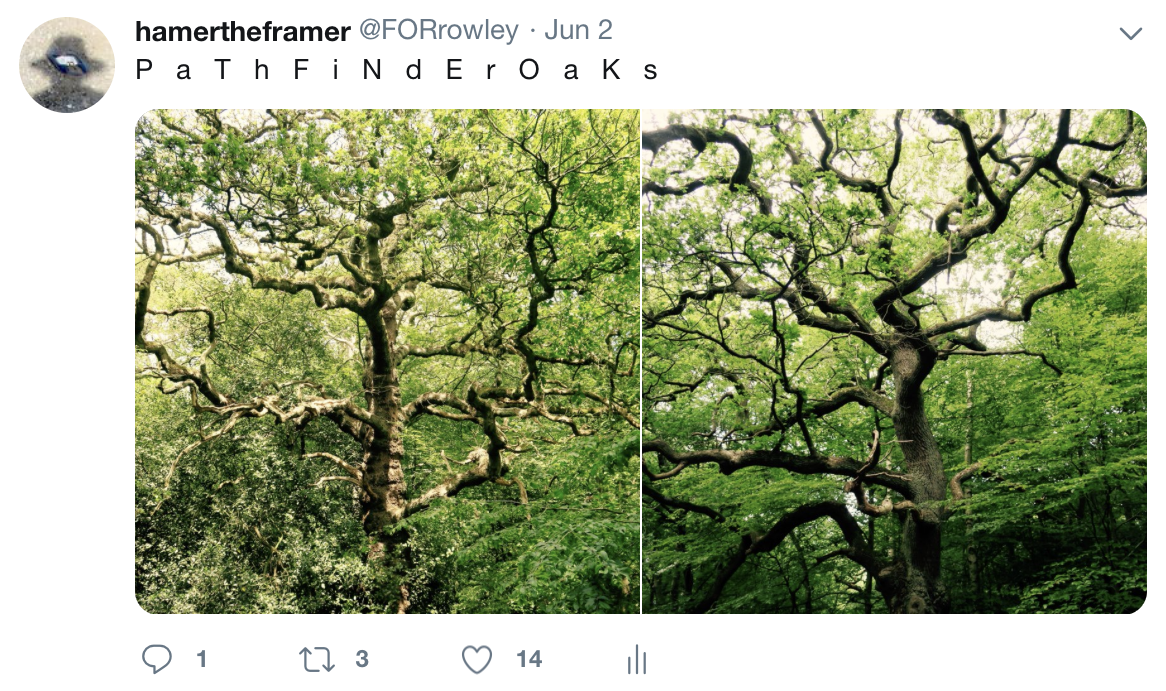

P a T h F i N d E r O a K

This “monarch of the forest” stands in a clearing at the junction of several rides between Fairmead Bottom and Connaught Water. Alternate names for this Quercus robur are Cuckoo Oak, Bedford’s Oak and Grimston’s Oak. The latter is the one most frequently used. J T Bedford was involved in the battle to save Epping Forest from destruction in the 1870s. Robert Grimston was a 19th Century cricketer who died in 1884. The tree is estimated to be about 350 years old.

It’s one of the few ‘stand alone’ trees in the forest, designated on the map as a landmark tree, so a suitable place for a group photo (thanks to a passing fellow tree pilgrim).

And another I Ching hexagram

The dancing oak of Strawberry Hill Ponds

Earl’s Path Pond

Then down the Green Ride and off to the side, along the winding path of Loughton Brook.

A sandy headland caught in a narrow meander.

Guardian hornbeams along the way, all twisting sinew and muscle.

This stretch was new, an understorey adventure all the way to Baldwins Pond, then the familiar climb up the hill to the Foresters Arms, and afterwards the always surprising rediscovery of the Lost Pond.

It seems like everyone who was ever here has left their mark in its visitor’s book. The trees all around are carved with souvenir glyphs and tags. The first time I ever came here forty years ago I climbed a tree impaled with metal rungs, though now it’s unsurprisingly no more, long gone and just a memory.

But that first time I overlooked the greatest treasure, the Lost Pond coppard, a great coppiced beech, later pollarded, and then cast adrift for centuries, hiding place of countless lost woodland wanderers.

P a T h F i N d E r O a K

And then headlong into Loughton Camp.

Loughton Camp is an Iron Age (~500 BC) hill fort in Epping Forest, one mile (1.6 km) northwest of the town of Loughton.

The camp’s earthworks cover an area of approximately 10 acres (4 hectares) and are visible today as a low bank and ditch encircling the main camp. The banks were most probably once a single high rampart, used for defence and the appearance of the ditch suggests it was once very wide and deep in places.

The camp lies on one of the highest points in the surrounding area, on a ridge of high ground, likely to have once been strategic. It is speculated that the camp was used by the Trinovantes in defence against the Catuvellauni. Its elevation suggests that the camp was possibly once a lookout post. However, it may have simply been used as fortification for protection of cattle. A stone Iron Age grain millstone (quern) was found close by. More colourfully, local legend has it that Boudica used the camp, and that Ambresbury Banks was the site of her defeat in AD61 however there is no evidence to corroborate this.

The southwestern edge of the camp falls away sharply to an area known as Kate’s Cellar (a hermit who reputedly once lived in this area of the forest). An early 19th Century map shows Dick Turpin’s hideout here (there are a number of locations within Epping Forest’s 6,000 acres (24 km2) which claim the same).

The camp was ‘discovered’ by Mr Benjamin Harris Cowper in 1872. The first archaeology carried out was by General Pitt-Rivers in 1881. In 1882 the Essex Field Club further excavated the banks.

A corresponding camp Ambresbury Banks exists closer to the town of Epping. Both are Scheduled Ancient Earthworks and, as such, must only be explored on foot.

Despite the No Cycling signs there are always mountain bikers here, riding the banks and hollows as

if this ancient monument was built for them as a scrambling track, before bicycles had been invented.

Merlin and I have been walking the forest for two hours or so when we reach one of Epping’s great pollard beech groves. Pollarding – the pruning of the upper branches of a tree to promote dense growth – keeps trees alive for longer, indeed can enter them into an almost indefinite fairy-tale time of longevity. Here in the grove, long waving trunks yearn up to the sun. Through their leaves falls a green sub-sea light. It feels as if we are swimming through a kelp forest…

Rivers of sap flow in the trees around us. If we were right now to lay a stethoscope to the bark of a birch or beech, we would hear the sap bubbling and crackling as it moves through the trunk…

I feel a quick, eerie sense of the world shifting irreversibly around me. Ground shivering beneath feet, knees, skin. ‘If only your mind were a slightly greener thing, we’d drown you in meaning…’ I glance down, try to trance the soil into transparency such that I can see its hidden infrastructure: millions of fungal skeins suspended between tapering tree roots, their prolific liaisons creating a gossamer web at least as intricate as the cables and fibers that hang beneath our cities. What’s the haunting phrase I’ve heard used to describe the realm of fungi? ‘The kingdom of the grey’. It speaks of fungi’s utter otherness, the challenges they issue to our usual models of time, space, and species…

“You look at the network,” says Merlin, “and then it starts to look back at you.”

The word for world is forest…

I find myself in a grove of pollard beeches atop a prehistoric earthwork. Under one of them, children have built a den of sticks and boughs, resting them against a low branch to form a crooked timber tent that is long enough for me to sleep in. It is an invitation I cannot refuse, so I creep inside the den and lie down, looking up through its slats at branches, stars, satellites. I feel myself suddenly – strongly – surrounded by beings whose ways of relating to one another are dimly but powerfully perceptible, as if seen through thick gauze. The sensation is at once comforting and lonely-making.

Owl hoot. Dog bark. Back in the clearing the fire dims, song falls silent. The canopy of the pollards spreads above me, whispering in the night breeze. ‘There’s something you need to hear…’ Seeking sleep, my mind follows leaf to branch, branch to trunk, trunk to root, and from there down along the hyphae that web the earth below.

All the way back to the dancing oak of Strawberry Hill Ponds,

and a herd of Longhorns at Fairmead Bottom,

and a mile further on, another herd by Butler’s Retreat Pond, back where we started from.

A circular walk in Epping Forest

※

23 June 2019

Three weeks later we came back to get entangled once again. Each time we try to follow a new route and explore a different quarter of the forest. And the more we get lost, the more we find we’ve been here before. And the more we map all the ways through the forest, the more complicated it becomes.

There are footpaths and roads, bridleways and mountain bike trails, each with a myriad headphone soundtracks. There are birdsong frequencies, waterbird wavelengths, echoes of cuckoos and magpies.

There are light ways and dark ways, right ways and wrong ways.

Thistles and grasses, and all their photosynthetic pathways.

I kneel down and I’m drawn in to the arc of a grasshopper and the flight of a moth.

There are rabbit runs and foxtrots and vascular highways through the branches of trees.

A signpost points out terrestrial routes

and a silver birch elbows its way to the sky.

A seed carried by a bird is a stitch in time.

Deer tracks and slug trails and mycorrhizal threads of subterranean fungus.

It’s all tied together in a web of call and response.

Here and there and back again.

A spaghetti junction in every dimension.

A cosmic web of connections

until we pull the plug…

※

The Understory: Robert Macfarlane

※

Planting a trillion trees to help stop global warming was written especially for you. Have you started planting?

I planted three, so just nine hundred ninety-nine billion nine hundred ninety-nine million nine hundred ninety-nine thousand nine hundred ninety-seven to go. I’ve got a Black locust (transplanted from a garden centre), a walnut (grown from seed, memento of my mother-in-law’s garden) and a tree-of-heaven (self-seeded conveniently in a flower pot). I’m not too sure about the mass plantation idea, I think trees should be encouraged to plant themselves wherever possible. But we can help and I hope you’re helping too Hank.