The view from our room in Lincoln on our last morning, looking towards the rising sun, the cathedral silhouetted through the trees, reminded of the ancient weather forecasting rhyme – Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. Red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning. But we had our hearts set on a walk before returning to London, so the more we looked, the more we convinced ourselves it was not red at all, but actually sky-blue pink. But it was the most sun we saw all day.

We were inspired to walk by an article in a local magazine, pretty much the first thing I’d read when we arrived a couple of days earlier, and reassuringly written by fellow Twitterer @maximpetergriff.

We came east from Lincoln to where the flatlands wrinkle and fold themselves briefly into the Wolds.

We left the car on Front Street in the village of Tealby and set out along the Viking Way.

The hollow places under the hawthorns were smooth-worn sheep-shelters, but empty for now, a sign the sheep had also ignored the shepherd’s warning. Maybe the sky’s promise of rain had been broken.

We waited under a coppiced hedgerow ash.

A flock of starlings forming murmuration.

A darkening sky forming precipitation.

On a clear day you can see Lincoln Cathedral from here.

But not today.

We came up the hill to the derelict Castle Farm. Fifty years ago a ruin like this was my playground.

We sheltered awhile in Bedlam Plantation.

Shepherd’s Warning

Then in the rough pasture below, we came upon a small flock of spectacular sheep.

And in the next field we found another flock, and their protectors, a couple of geese who

honked at us angrily and followed us along the path to make sure we were up to no mischief.

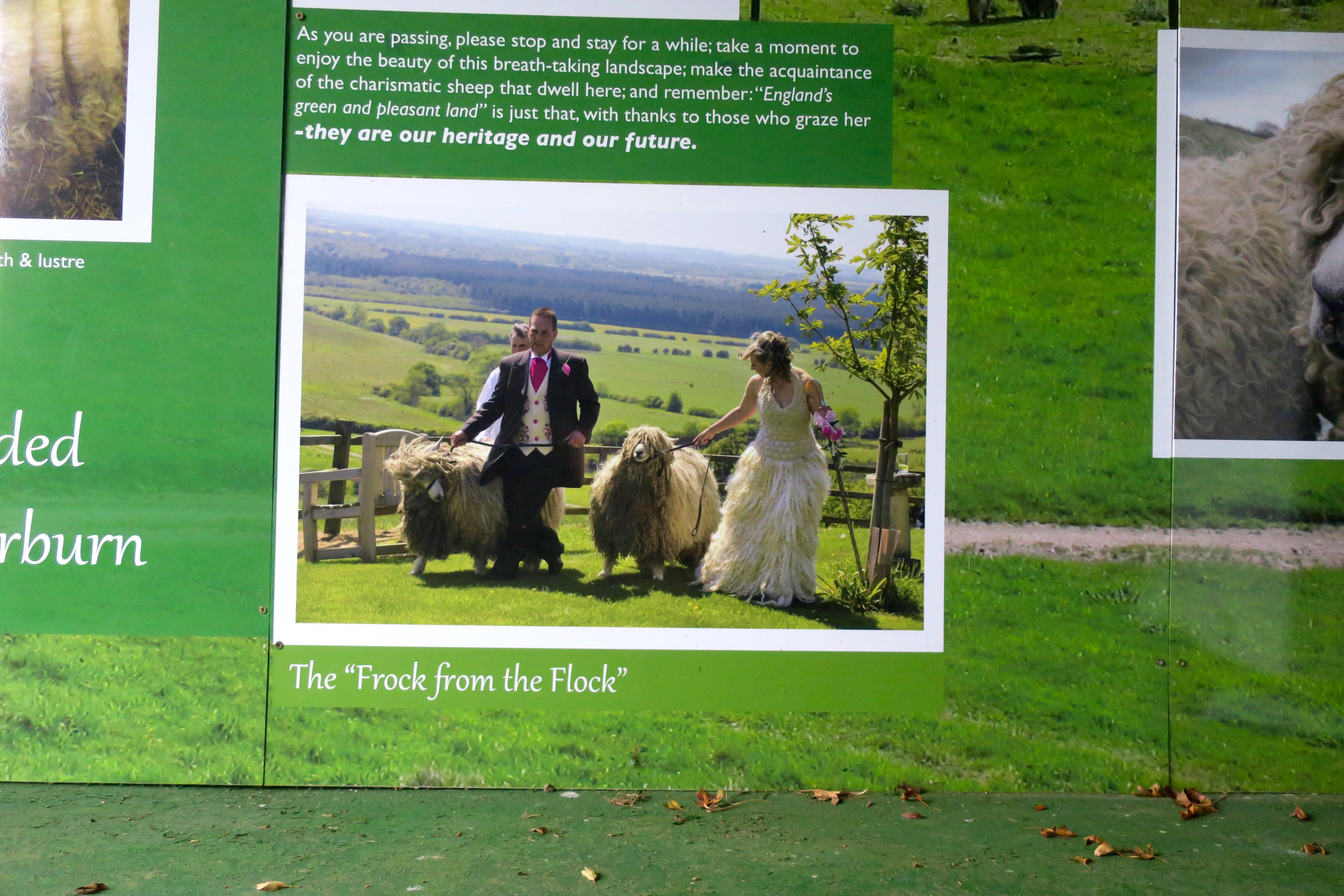

The Risby Flock of Lincoln Longwools

The sheep even have their own shop.

www.risbygrangelongwools.co.uk

We continued along the ridge by Risby Manor Farm, looking west into the fading light,

scouring the horizon but still unable to see the promised vision of Lincoln Cathedral.

The ground fell away beside us to where a herd of deer watched us intently. Our path descended steeply past more sheep then through a high-fenced paddock where the deer continued to watch.

Across the valley and up the other side and through another field of grazing deer.

To arrive at All Saints Church above the village of Walesby.

The ash trees in the churchyard remind me of the Hardy Ash.

The church dates from 1172 with a 13th century Norman tower, built on the site of a former Saxon church. Once the centre of a medieval settlement, it now stands alone amidst fields of overgrown earthworks, remains of one of the many Lincolnshire lost villages abandoned to the Black Death.

All Saints Walesby is also known as the Ramblers’ Church.

The Grimsby & District Wayfarers Association gave the east window of this lady chapel in memory of lovers of the countryside whose annual pilgrimages to this church began in 1932. Dedicated 1950.

The villages of the Lincolnshire Wolds have many interesting and attractive old churches, and one of the most remarkable is the ‘Old Church’ of All Saints, remote on a hilltop above Walesby. It’s ‘old’ in that it was replaced by a newer version in 1913, and in the succeeding years became dilapidated and run-down. But it was never deconsecrated and, in the early 1930s, a local rambling club began making an annual pilgrimage to the church. Twenty years later the Grimsby and District Wayfarers’ Association dedicated the East Window of the Lady Chapel to ‘lovers of the countryside’, with a stained-glass depiction of walkers and cyclists. Local ramblers still hold an annual service at what is now referred to as ‘the Ramblers’ Church’, and most appropriately the Viking Way long distance footpath passes through the churchyard.

Although repairs have been carried out over the last 20 years to protect All Saints from further weathering and decay, it retains its simple medieval character, a splendid example of what’s known as the Norman-Transitional period. Several old, boxed pews remain, while another interesting feature is the old stairway behind the pulpit which leads to the well-preserved rood loft – the name for the gallery above the rood screen which separates the nave (the main part of the church where the congregation sit) from the chancel (where the clergy and choir sit).

The more we looked around the church the more it seemed we were also being watched.

From the church, the glorious views can include the towers of Lincoln Cathedral on a clear day. A Roman villa was unearthed to the east of the church, and a simple Saxon building almost certainly pre-dates the present church (built mainly between the 12th and 15th centuries). Its admirers include John Betjeman, who described All Saints as ‘an exceptionally attractive church, worth bicycling 12 miles against the wind to see’.

※

We said goodbye to All Saints and its churchyard ash trees, and then more down along the steep holloway into the village. Yesterday I’d bought a pretty little book by a ‘local author’, and fellow Twitterer @WillCohu, at Lindum Books in Lincoln and I’d been enjoying reading about ash trees…

Ash trees are lazy; they don’t get out of bed till late in the year. When most other trees are busy doing wholesome spring things, the ash will yawn, turn in its bed and continue to dream of its excesses of the previous autumn, those wild nights swaying in the November winds. It loves winter. On stormy nights, the ash trees sway to and fro like mad old bastards dancing in the nude, their massive limbs wiping the clouds from the moon. Sometimes they do one hula too many, go pop and crack in two, just where a dose of the old rot has got them.

Provoked by the warmth of the spring sun, the ash tree’s libido eventually stirs, and well in advance of its foliage it will push out flowers, like little tufts of purple broccoli on the bare twigs. Within its purple haze, still half asleep, the ash is busily fornicating, probably with itself. Ash trees can be male, female or both: they can change gender from year to year or have flowers of different sexes on the same branch. They are transsexual hermaphrodites. How convenient. This bisexual-transsexual-hermaphrodite creature wakes up late, pokes out a few flowers, plays with itself in the breeze, gets pollinated and goes back to sleep. Some years it can’t be bothered to produce any progeny at all, but when it has a good year, the seeds hang in bunches that crack thick limbs. Nonetheless, because it comes into leaf later than other trees, there is more light under its canopy in spring; and ash woodland can be rich in flowers.

Then further on down the lane there was hazel –

In early winter, fawn-coloured hazel catkins (those “lamb’s-tails” of childhood) appear on spindly twigs. The leaves are big and floppy like some withered faddish vegetable. In late summer you might be lucky enough to find a few nuts if you can beat the squirrels to them.

We continued along the macabre sounding Catskin Lane, where perhaps there was room to skin a cat, but maybe more likely it was a tongue-slip for Catkins Lane. Nowadays it should be Deerskin Lane.

The road led between more high-fenced paddocks of grazing deer, past fields of Walesby venison.

Walking the Way to Health

Then through another field of Lincolnshire Longwools. But as we approached they gathered together by the gate, as if to block our way, and an excitable couple nervously started head-butting each other. It didn’t look promising. We skirted around to the left and climbed the fence rather than go through the gate and risk letting them into the next field, which was home to a different kind of sheep.

Aw, go on, let us come with you.

And then, at last, a view of the towers of Lincoln Cathedral, there on the horizon. Can’t you see it?

Until finally we arrived back in Tealby and lunch at The King’s Head.

※

Walk the walk: Churches of the Wolds