I’d sent out a request via Twitter saying we were planning a weekend in Cambridge and could anyone recommend a woodland walk nearby. I received an intriguing reply from Steve Pocock – Oh, check out Hayley Wood to west of Cambridge. That was one of Oliver Rackham’s stomping grounds where he did a lot of his work on medieval woodlands. Features in his books.

The tweet came with photos attached, suggesting Steve had done some research before replying. I was touched. How could we resist? Hayley Wood beckoned – 120 acres enclosed by ancient woodbanks.

The wood is approached by a path running alongside Hayley Lane between a medieval mixed hedge on the right and a newly laid hawthorn hedge on the left.

The hedge alongside Hayley Lane is one of the few ancient hedges in Cambridgeshire; in the middle ages it divided the meadow of Little Gransden from the arable land of Longstowe. This ancient hedge is a mixture of many different trees and shrubs. Some, like guelder rose and wayfaring tree, often grow in old hedges. It is not kept trim with a modern hedge-cutter, but laid in the traditional manner. Strong trunks of hawthorn and other shrubs in the hedge are partly cut through, allowing them to be bent almost horizontally and weaker stems are woven vertically through these to make a living fence. The hedge is then left to grow for 5 to 10 years before it needs laying again.

We arrived at the northern edge of the wood, bordered by a path along the old Cambridge to Bedford railway line. The wood is surrounded by a high deer fence to protect the renewed growth of coppiced trees and the rare flowers that grow here.

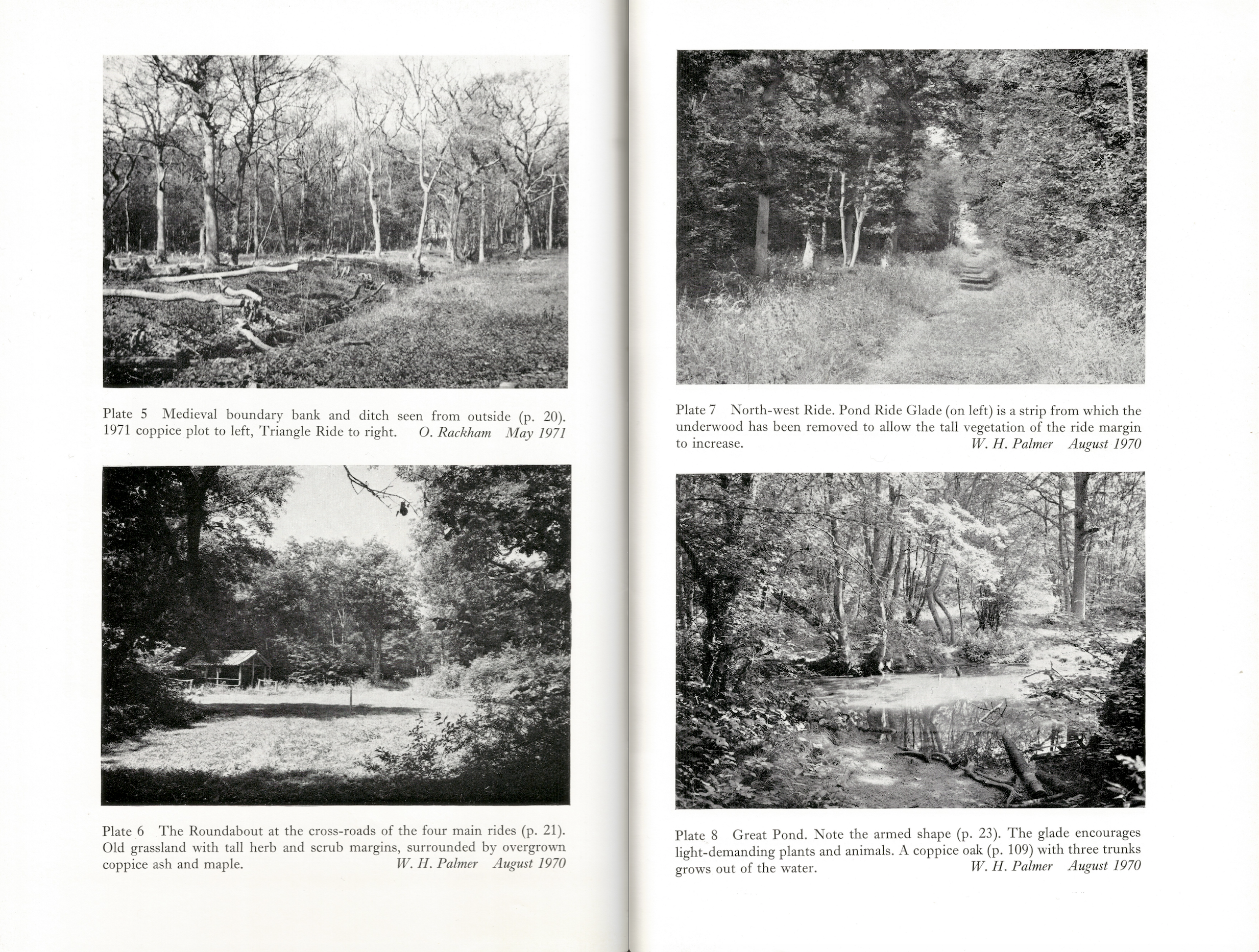

The first section is known as the Triangle and it is full of tall slender trees reaching for the light, including some of the tallest hawthorns I think I’ve ever seen.

The first part of the wood that you enter was a field a century ago when the railway cut it off from the surrounding farmland. Oaks and hawthorns appeared from seed dropped by birds and a wood developed. Any piece of land that is no longer used will eventually become woodland of some sort, and conservationists spend much of their time digging up trees to prevent heaths and grassland from turning into woodland. The railway was abandoned in 1969. If left alone it too would become woodland and the rare grassland plants which thrive on the dry gravel would be lost together with the many butterflies which feed on them.

Lesser celandine (Ficaria verna)

Coppicing in Hayley Wood

For thousands of years, coppicing has provided people with firewood and building materials. It was widespread until the 19th century when coal increasingly replaced firewood as fuel, leading to a fall in demand for coppice products. In the 20th century, war and the use of new materials led to further decline and to many woods becoming neglected.

From the 1950s to the 1970s many woods were destroyed and replaced by fields or conifer plantations. Small scale commercial coppicing still continues, while coppicing for conservation purposes is becoming more widespread.

Coppicing dramatically increases the amount of light and warmth that reaches the woodland floor, which encourages plant and insect life. In the spring following cutting, tree stumps send up vigorous young shoots and slowly over a number of years the canopy will close again. Each stage of regrowth supports different plants and animals, which can move around the plots as conditions change.

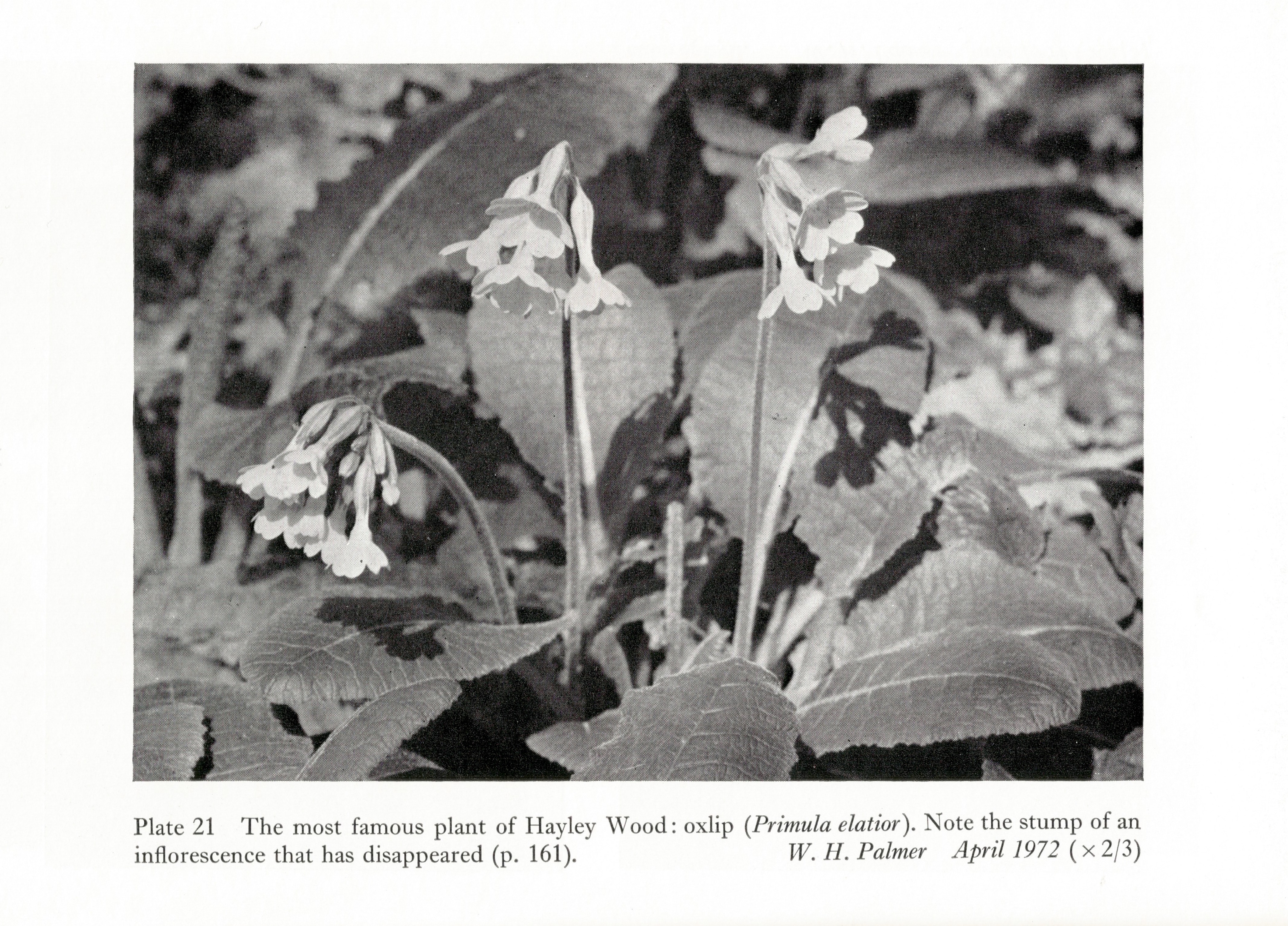

In the newly coppiced areas there is a flush of spring flowers, such as oxlip and wood anemone, which offer nectar for butterflies and other insects. Birds are provided with an array of nesting and foraging habitats. As you wander down the ride, look out for woodcock, blackcap and chiffchaff in and around the coppice plots.

Hayley Wood is an ancient woodland that has been coppiced since at least the 1250s. Coppicing ceased in the 1920s, but in 1963 Hayley became one of the first sites in the country to reintroduce the practice for the benefit of wildlife.

There are now 14 one-acre coppice plots – seven either side of the main ride – dominated by ash and hazel. We cut them in sequence, one every winter. The boundaries of the plots are marked with oak posts.

As you walk along the main ride, you can see the continuous change in vegetation from the open ground of the most recently cut plot to the dense thicket of the plot cut 14 years ago. We coppice a narrow strip along the ride more frequently to keep it open and sunny.

In each coppice plot there are some larger trees, mainly oaks, known as standards. Selected standards are periodically removed to prevent them shading out the coppice. Others are left to become old, gnarled or hollow veteran trees, which provide valuable habitat for specialised insects.

Deer are an important part of our wildlife, but can do irreparable damage to woodland flora and degrade the habitat for other wildlife if present in too high a number. The fence around the wood helps us to limit deer numbers to a sustainable level.

The edge of the wood proper is demarcated by a bank and ditch.

The Main Ride with ditches either side and a high seat for deer culling. Despite the high perimeter fence, it seems deer are still able to find a way into the wood, though we saw none this day.

It was Earth Day and the first few days of sunshine we’d seen for months. It was also the weekend when the first newborn leaves began to appear on the trees.

Hayley Wood is important today as a nature reserve sheltering a variety of plants and animals, but until the last century it was valuable as a source of wood and timber. Woods were managed, cropped like farmland, and the way in which they were managed was important enough to be detailed in historical documents like the Ely Coucher Book. It is from documents like these that the pattern of management is known.

When felled most British trees regrow from the stump or roots to produce new stems which can in turn be cut again and again. Managing woodland in this way is called coppicing, and trees which are coppiced are known as underwood. They develop large stumps or stools, from which grow a number of trunks. In the past, part of Hayley Wood was felled once every seven years and some of the rods and poles which were cut – ash, maple, hazel and sallow – were used for fuel or burnt to make charcoal for forges. The better ones were used to make furniture, in building or fencing, as hurdles and stakes, or tool-handles, thatching rods, and all sorts of small wooden articles which today would be made of manmade materials. Scattered among the underwood stools were standards: timber trees, usually oaks, left to grow until they were big enough to make beams and planks. The oak bark was used for tanning, and branches too small for timber were added to the firewood, bound into faggots with the smallest of the underwood. Coppicing keeps trees alive much longer than they would survive if undisturbed. There are many ancient coppice stools in Hayley Wood, ash and maple trees 400 – 600 years old. In contrast the oldest oak found so far began to grow in 1765, just over 200 years ago.

Woodland was more valuable than arable land in the middle ages, and immense labour went into woodland conservation. The boundaries were protected by a bank and ditch, which can still be seen around Hayley Wood. A hedge growing on the top of the bank would have kept out sheep and cattle which would eat the young shoots growing from the coppice stools. Trees growing on the bank were pollarded, their branches cut high up the trunk so that cattle would not eat the new growth. The pollards were sometimes cut in summer so that livestock could be fed on the leaves of the branches. They are distinctive trees and were often used as landmarks.

The value of woodland is clear from medieval documents which describe in detail how they were to be managed. A lease of ‘Halye Wood’ in 1584 not only states when the underwood should be cut “at times suitable for the felling of woods”, but also gives careful instructions “he… shall well and sufficiently enclose and encoppice [it] with coppice fences, and shall guard and protect it from the bite, trampling and damage of animals, without putting in any horses or other animals which may be able to hurt the regrowth of the same woods and underwoods, during the statutory term… And shall spare and leave sufficient Stadells [small trees to grow as timber] in every acre…” Timber trees remained the property of the owner, who would fell them only when timber was needed.

If Hayley Wood was not managed, the rides, coppiced areas, glades and wood edge would be overgrown and their plants and animals would disappear. Coppicing may look destructive, but it is essential to preserve the variety of habitats found in the wood. Many woodland plants, insects and birds cannot live in shade all the time; they need the years of light after coppicing followed by years of increasing shade as the underwood grows.

The rides and other grassy areas are mown regularly, but only part of the wood is coppiced. Plaques give dates of cutting on each plot along the main ride – the underwood is cut at longer intervals than in medieval times because the shade of timber trees and nibbling by deer slow its regrowth. Timber oaks are rarely felled now, and have grown much bigger than would have been usual in the middle ages, but the underwood is still cut in autumn and winter. Instead of the old axes and bills we use mainly chainsaws, which have the same effect but require less time and effort.

Deer are now more common in England than they have been for a thousand years. Hayley Wood swarms with fallow deer, whose ancestors probably escaped from Waresley Park, and with Chinese muntjac. Like the cattle and sheep that the woodbank kept out of medieval woods, fallow deer eat the young shoots of trees growing after coppicing. In places the ash trees are pollarded instead of coppiced to keep the new growth out of the reach of browsing deer. There are high fences around part of the wood to keep the deer out.

Wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa)

Halfway down the Main Ride we came to a crossroads where we found a small wooden hut displaying vital information about woodland management and the history, ecology, flora and fauna of Hayley Wood. I’ve copied lots of it into this blogpost. Most of the text in italics comes from those information boards. With thanks to The Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire.

We continued straight ahead.

Lesser celandine (Ficaria verna) and Wood violet (Viola riviniana)

Oxlip (Primula elatior)

The Oxlip

This is a special Primula, not to be confused with the hybrid between primrose and cowslip. It grows only in two small areas of Eastern England. Like anemone and Herb Paris it is an indicator of ancient woodland, for it seldom grows anywhere else: there are still some oxlips growing in the grass of the old railway alongside the wood, a reminder that the railway was built on ancient woodland. There are a few oxlips growing in the Triangle although they are abundant only a few metres away.

Hayley Wood was made a nature reserve in part to protect the oxlip which grows here in vast numbers and completely replaces the primrose. Oxlips flower and seed profusely in the sunlight after coppicing but unfortunately deer love the flowers and have eaten millions of plants. Most of the remaining oxlips now survive inside deer fences.

Common bluebell (Hyacinthoides non-scripta)

Hayley Wood lies on a flat hilltop, covered with a great thickness of boulder clay laid down during and after the last Ice Age. In wet springs the wood is flooded because the rainwater cannot soak through the heavy clay and it is this flooding that defines the different habitats within the wood. Where flooding occurs in the middle and north of the wood there is a great variety of plants including the oxlip. Where drainage is a little better there are carpets of bluebells, while on comparatively sloping, well-drained areas the plant cover is dull, little more than sheets of dog’s-mercury. This is a vigorous plant but it cannot tolerate the same level of moisture as the bluebell which in turn does not do well in the wettest areas where oxlip is found. The wetness of the wood is essential: to improve the drainage would destroy much of the value of Hayley Wood as a nature reserve.

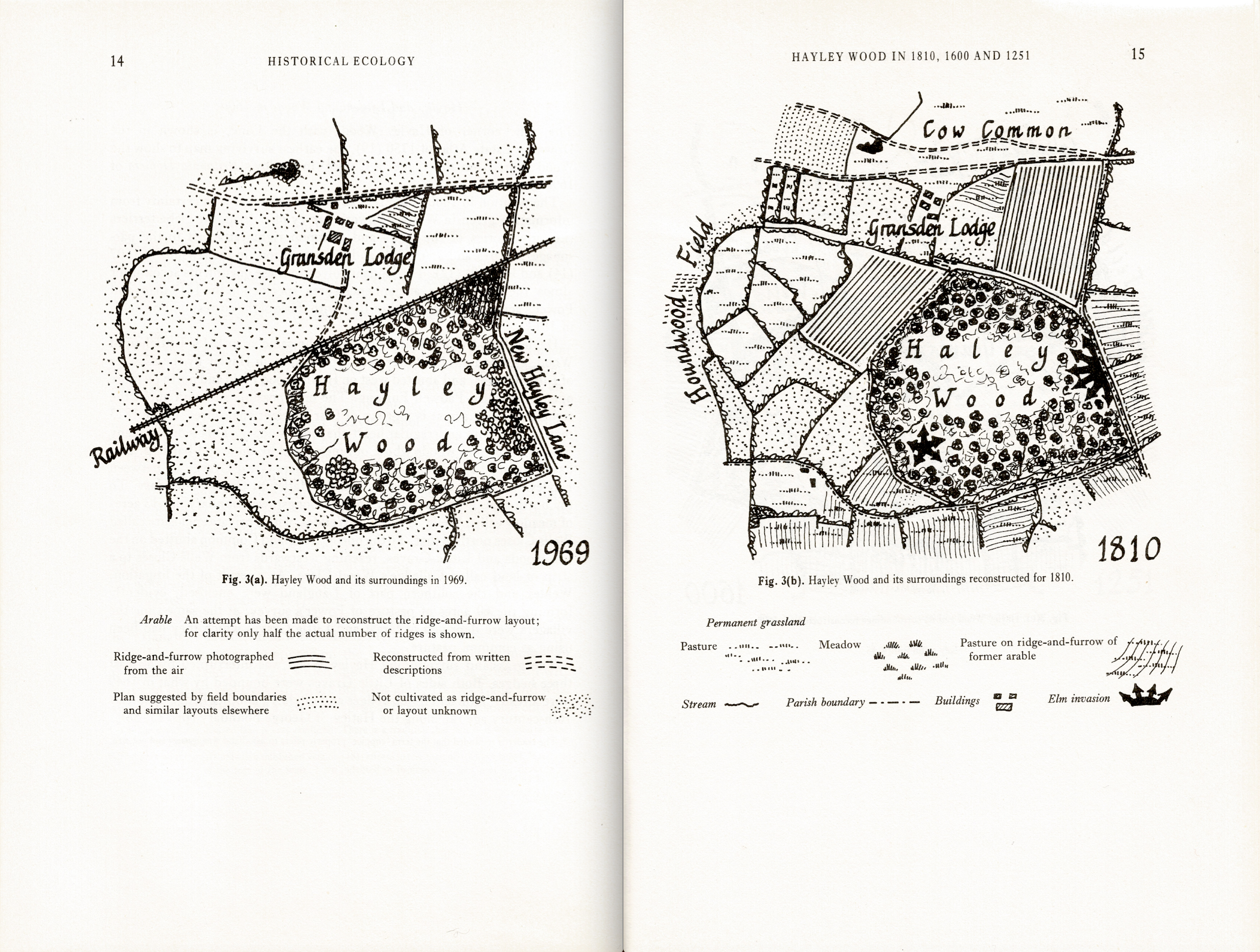

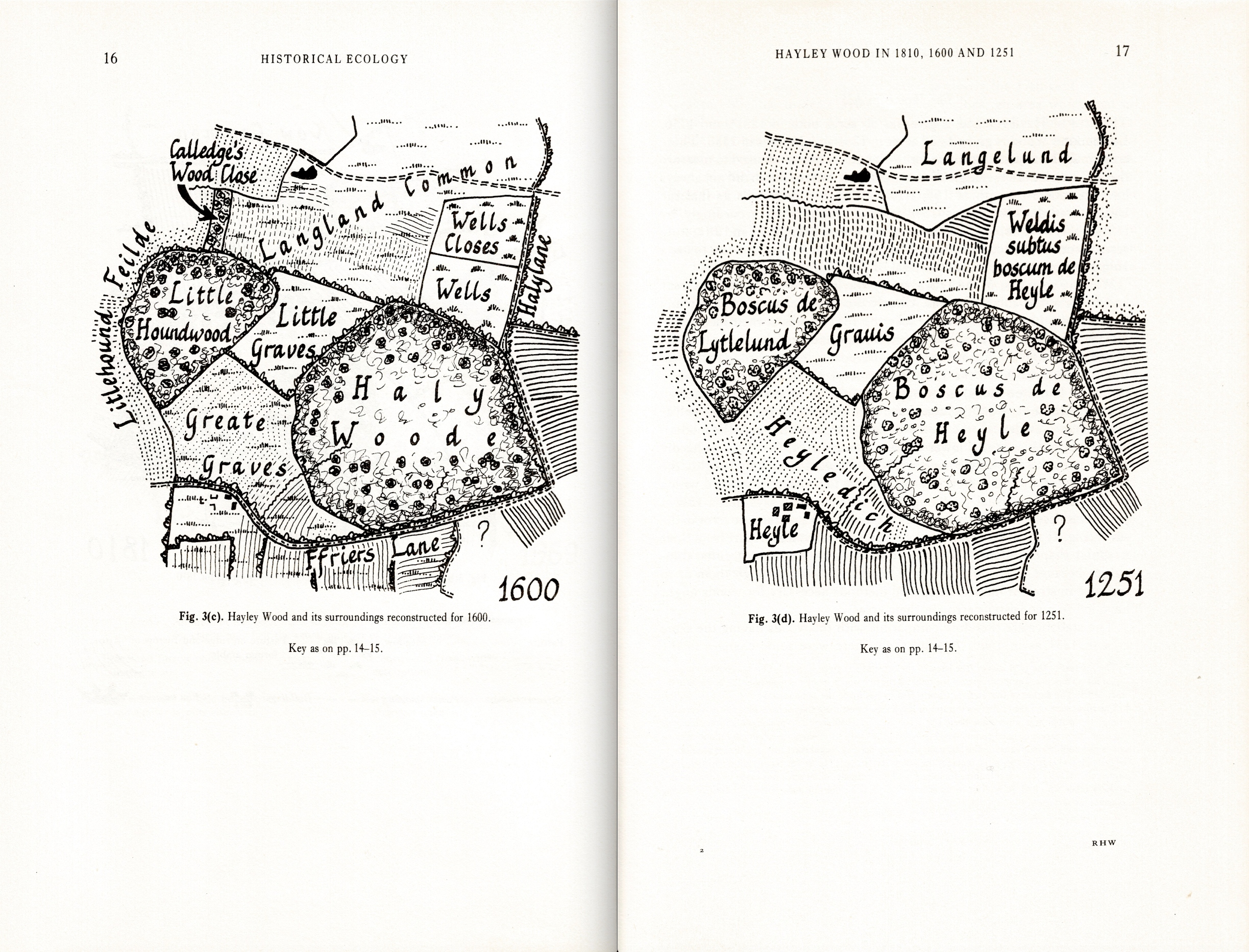

This is an ancient wood. It was probably named after a nearby settlement, Hayley Grange, which was first mentioned in 1164 but was deserted some time after 1316. For at least a thousand years the wood has been an island of woodland in the midst of fields. Until very recently Hayley Wood was protected and conserved; managed for the wood and timber which provided fuel and building materials.

England was made out of the wildwood – the boundless trees that covered the country from end to end after the last Ice Age. For four thousand years down to the Iron Age, farmers were busy grubbing out trees and making new fields. In Roman times there was probably still a great deal of woodland, but it was no longer untrodden wildwood: a main Roman road runs within two miles of the wood on the east, and what may be an even earlier road passes two miles to the west.

People were living in the nearby villages in Anglo-Saxon times, rather more than 1000 years ago. When enlarging their fields into the remaining woods the early farmers had left certain areas as woodland and by 1066 the landscape was similar to what we know today, with many villages and large tracts of farmland surrounding isolated woods. The names Hayley, Hatley, Waresley and others end in -ley, from the Anglo-Saxon -leah meaning a clearing in the prehistoric wildwood. The ancient woods of West Cambridgeshire are small remnants of that wildwood: although centuries of management have influenced the appearance of the wood, there have been trees here since the last Ice Age. They survive because they are on outcrops of chalky Boulder Clay, a heavy wet soil unsuitable for ancient agriculture.

Hayley Wood is now well known as the largest surviving example of ancient woodland in a sparsely wooded area, and is famous for its population of oxlips, one of the many rare species found only in this rare habitat. Because of its historical interest and importance to wildlife Hayley Wood was bought in 1962, the first Nature Reserve purchased by what is now The Wildlife Trust.

As we came back along the Main Ride we stepped off the path to explore a coppice plot that had recently been cut, where we found a view of the wood from the top of a deer stalking tower.

Hayley Wood is a special place, a uniquely ancient habitat; we felt privileged to have found it and thankful for the recommendation. And then a few days later there was another. I picked up a tweet from Susan Oosthuizen – The enclosed, managed woodland at Hayley [haga, ‘hedge’ + lēah, ‘wood’] Wood, Cambs., was already ancient when the hedge was planted along the medieval lane leading to it c.800 yrs ago… And she told me of a book by Oliver Rackham. Next time I’ll take it with me.

We were fortunate to have visited at the right time just when the oxlips were in flower.

Your photograph of a huge tree’s shadow cast on the ground is terrific!

Thank you! That’s the ‘Roundabout’ at the centre of the wood and the tree-shadow is like a sundial. I reckon it’s about one o’clock.

I have never been in Hayley Wood, but I read about it in Rackham’s Woodlands. Your blog was almost like being there. I am writing you this, because I discuss Oliver Rackham’s fable (p. 78) in my forthcoming book

Leopoldine van Hogendorp Prosperetti, Woodland Imagery in Northern Art, c. 1500-1800: poetry and ecology- Lund Humphries, March, 2022.

I’m intrigued! I’ll look out for your book. Good luck.

I found it here. It looks great! I’m looking forward to March.

Hi!!! I am a fourth-year Rackham student from the University of Michigan who just finished reading “Rackham’s Woodlands.” Your blog is like a parallel dimension to your book

Dear Hudson, always wonderful to meet readers of Rackham…are you an English major, an environmentalist? I am always happy to help students or readers to look at things through “an ecological lens,”