The fox slowly and artfully began to materialise on the periphery of my conciousness and seep seamlessly into my paintings about five years ago. Today I class it as a major player in my lexicon of characters; those I call upon, or more likely those who call upon me.

The red fox, vulpes vulpes, is widespread throughout Europe and indeed its many and various relatives, coming in all shapes and sizes span the globe. An early chronicler of the fox was Aristotle who less than favourably labelled it as “wicked and villainous”. These words seem to have stuck like mud over the centuries. The baton was picked up and carried in the Reynard stories, translated by William Caxton in 1481 into English. The stories are passed down from Aesop, but they put the fox at the centre of the tales. Reynard’s abode is a wondrous, labyrinthine castle full of twists and turns and hiding places. This is obviously drawing parallels with the thinking passed down that the fox’s nature was crafty, canny, devious and able to spirit itself away at the drop of a hat.

The fox’s fiery coat has played its part in folklore; in Japan for instance the fox spirit is shape-shifter, it can put its tail between its legs and rub it with its paws until it ignites and becomes human. The very shape of the tail itself being flame-like was symbolic. Foxes are in fact often identified with fire, perhaps because they were said to be the animal that witches most commonly transformed themselves into. The association with the burning of witches and the fox’s coat was cemented.

I am a keen gardener and coincidentally the foxglove, digitalis, is one of my favourite flowers. I use it in large quantities for its luminosity in dark areas. I have always felt it had some magical properties and I was delighted to find out just how it got its name. An ancient name is fox-bells as the flower was seen to be able to ward off the Devil. Foxes were seen to be hunted almost to extinction for their brushes, so they turned to their vulpine gods for help and protection. The gods obliged by placing bells throughout the fields and woodlands to warn them of the approaching hunters. The bells lost their sound when the foxes were no longer threatened by superstitious hunters.

The fox in literature reaches its zenith for me in Mary Webb’s novel Gone To Earth. Written in 1917, it was Webb’s second full scale work as an English Romantic. She was born in 1881 in Shropshire, the county that she loved best and which inspired her all her life as an artist. Her most acclaimed novel, and for some her masterpiece, Precious Bane was written in 1924 three years before her death in 1927, and explores a lot of similar themes. The outsider in a close knit rural community. The overwhelming feeling of the natural world as mystical realm dripping with portents and symbolism. In Gone To Earth the heroine Hazel is a wild child of nature who befriends a young vixen and they become best friends. Hazel is pursued by the males in the novel like a fox in a hunt with ultimately the same tragic consequences. The fox is central to this sublime book as it also is in the Pressburger and Powell film of the novel made in 1950. The fox is totally central in Brian Carter’s novel A Black Fox Running, written in 1981. In a similar way that Watership Down created an interior voice for the rabbits, so Carter’s novel tells the story of a group of foxes living on Dartmoor from the point of view of the fox itself. Through the voice of the main protagonist Wulfgar, Carter is able, like Mary Webb, to weave and summon glorious poetic paeans to the ever changing but eternal drama of the natural world.

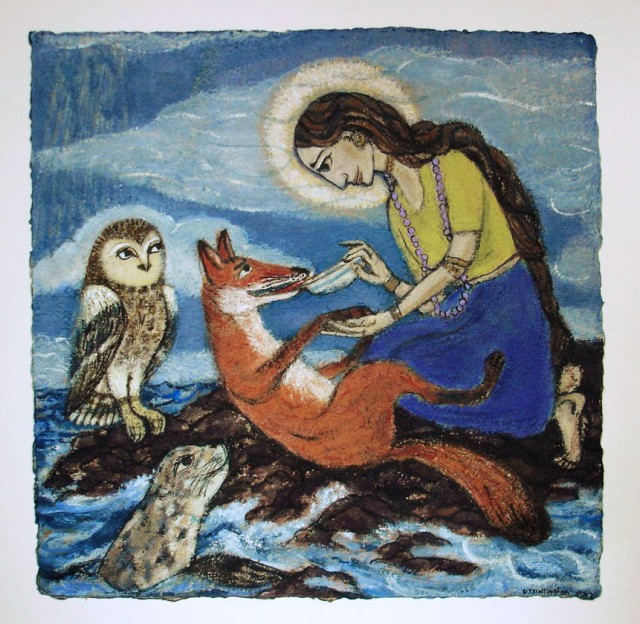

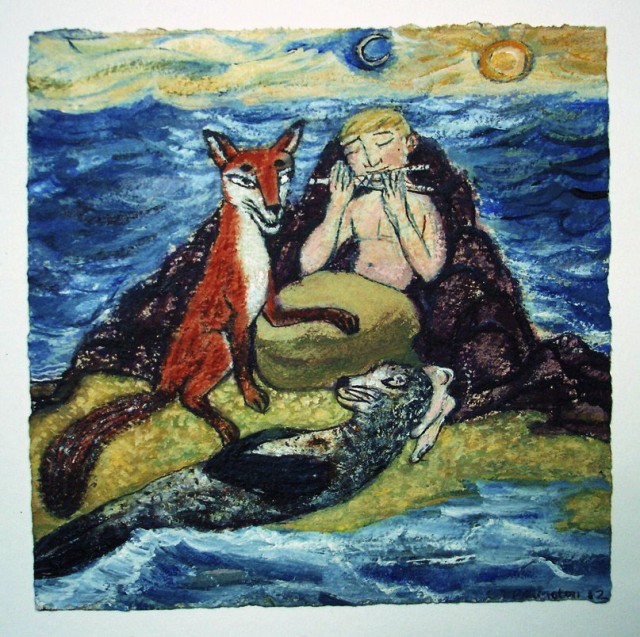

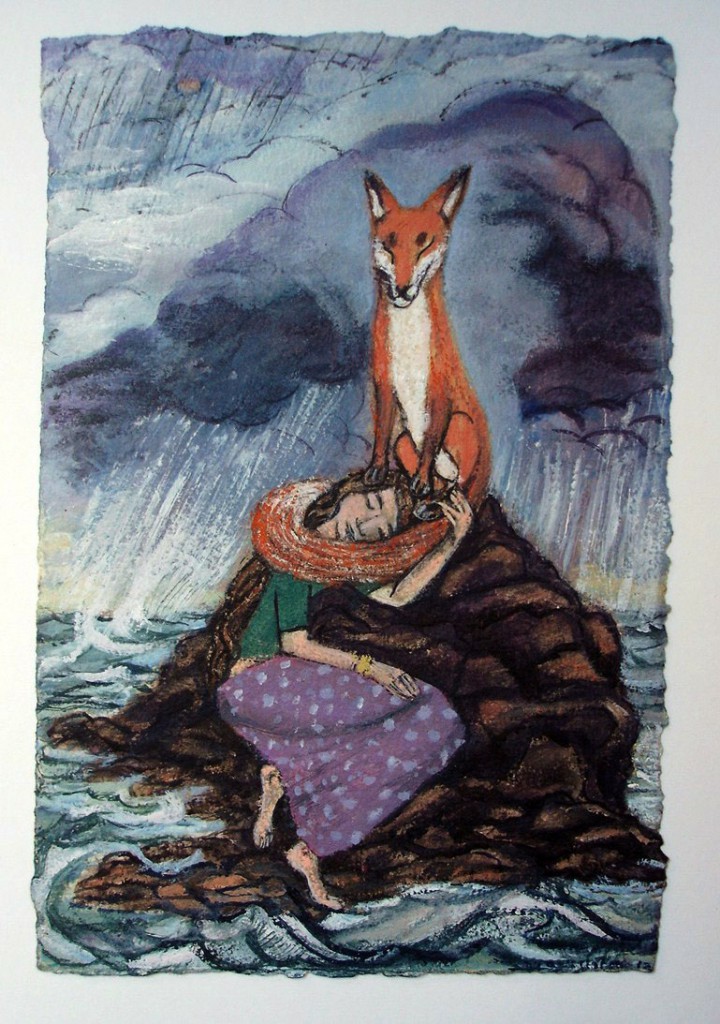

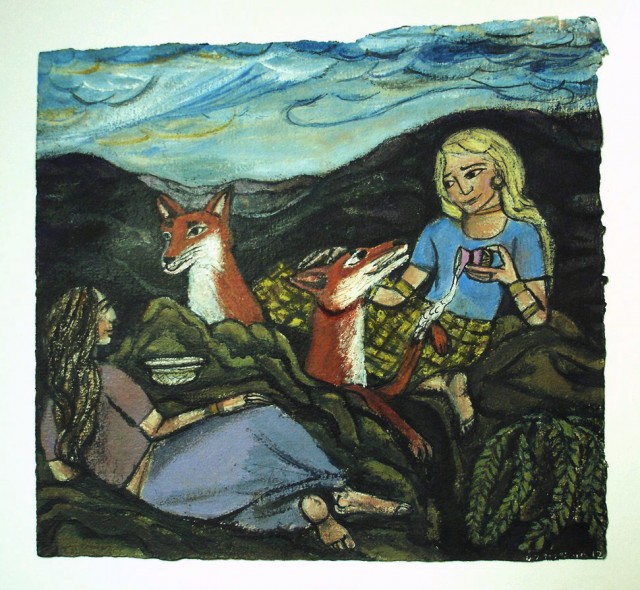

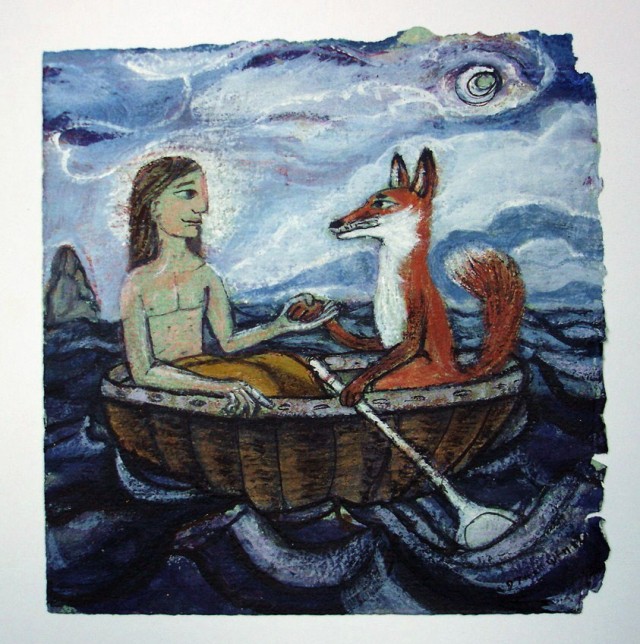

How I feel about the fox is a lot more ambivalent. I understand and somehow have coded in my brain the perceived character of the fox. However, for me the fox is a primal link between the human and the spirit world. In my paintings such as Healing Place, Medea and Balm, the fox is a symbol of our fragile ecosystem, reaching out to the human world for reconciliation. In Sentinel and Precious Cargo the fox is a protector, ancient and wise and a reminder of both the glorious rays of the sun and the slow ebbing of twilight into shadow.

I feel the fox will stay and linger in my work as long as it chooses. I can’t control its destiny or desire to roam. I only know that once I have locked its ethereal form onto paper, I am relieved in the way that I feel when a butterfly lands on my hand in the garden: it’s here now, enjoy it and wonder, but it’s not to be owned.

David Hollington / The Rowley Gallery