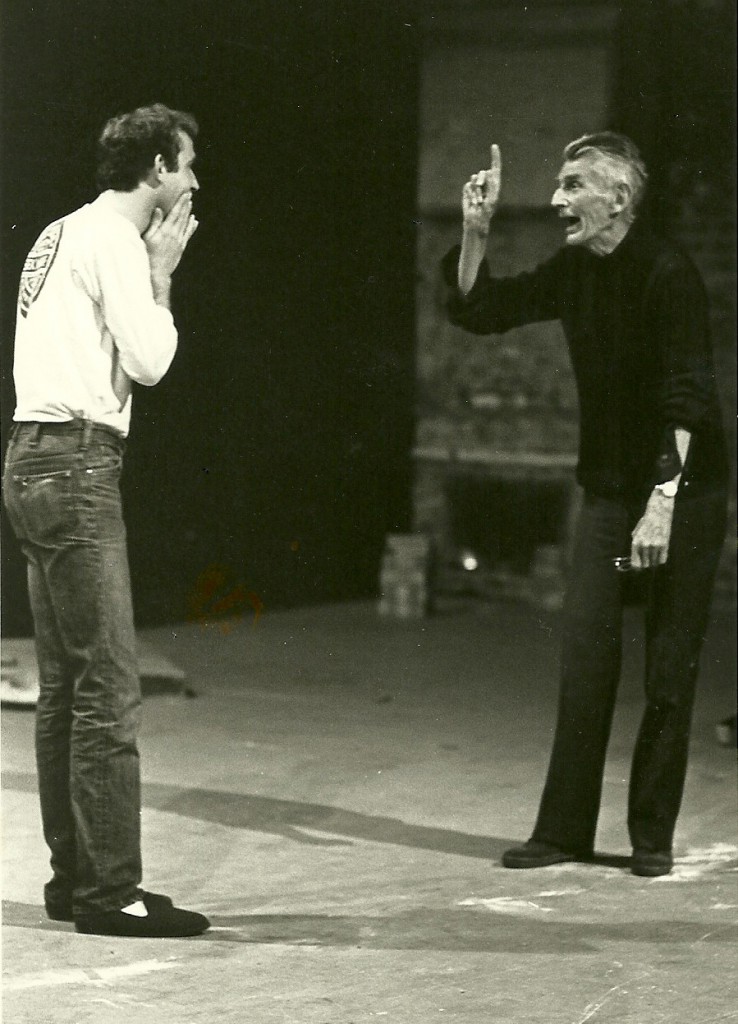

Samuel Beckett rehearsing Endgame and ‘having an idea’ with the San Quentin Drama Workshop at Riverside Studios in Hammersmith in 1980. I worked there intermittently in those days, even had a small exhibition of my paintings there, and the house photographer Chris Harris, knowing how much I loved Beckett, gave me a print of this photograph for my birthday.

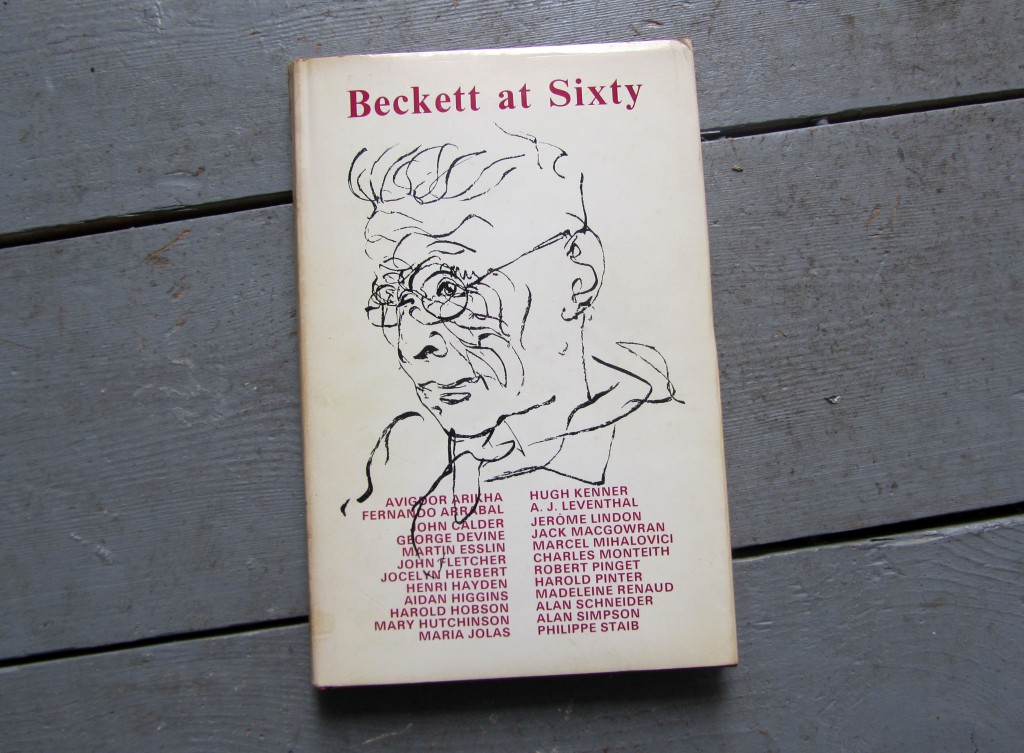

In the same year I acquired this book, Beckett At Sixty: A Festschrift, a celebration on his 60th year in 1966, with cover drawing by Avigdor Arikha. The introduction begins with this from John Calder, Beckett’s publisher:

Samuel Beckett was sixty on the 13th of April nineteen sixty-six, a Wednesday as it happens, and not a Friday, for he was born on a Friday the thirteenth. And not only a Friday the thirteenth, but a Good Friday the thirteenth…

Antony Gormley made this Tree for Waiting For Godot, the Good Friday cross replaced by a tree:

I love Beckett and this play. Having been brought up a Catholic and believing up to the age of 17 that redemption was the only way that life’s vicissitudes could have meaning, the realisation that the whole notion that anyone else’s suffering could redeem one’s own was wishful thinking marked the beginning of real responsibility. The need for a Tree that replaces the cross and that carries our responsibility to the natural world and our place within it was a need that I could not refuse. So this Tree is a signpost and a marker. Waiting for Godot had an important part to play in changing my consciousness from a child-like attachment to the consolations of religion to a realisation that it is the human that makes his own condition and making this object became a wonderful opportunity to reconsider human nature in nature.

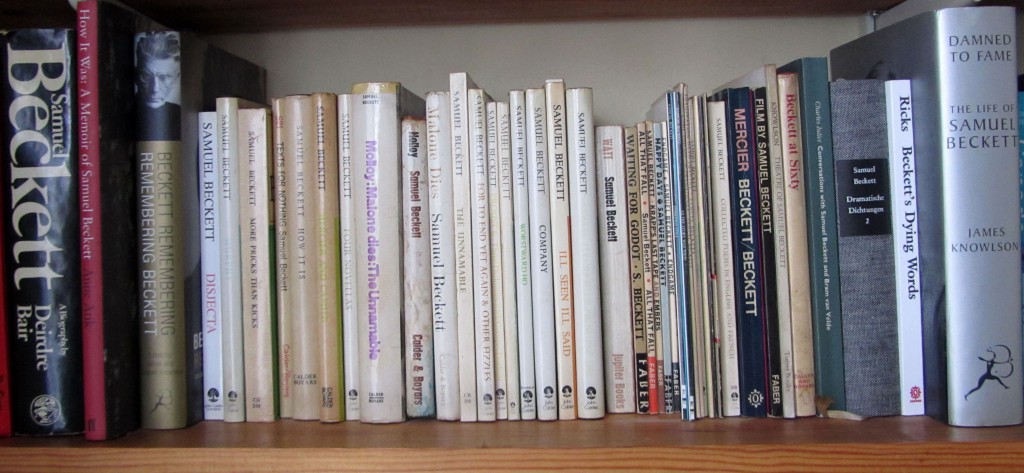

In 1980 I was 27; now 33 years later it is I who am sixty. So too is Waiting For Godot, first performed at the Théâtre du Babylone in Paris in 1953. I am as old as Godot, but I suppose I always was. I only just noticed. There’s still life in the old dog yet; we’re still waiting for Godot. It is a timeless play about the passing of time, like music, a divertimento, a shared experience, symbiosis, getting along. I love it.

Vladimir: That passed the time.

Estragon: It would have passed in any case.

Vladimir: Yes, but not so rapidly.

The Beckett International Foundation celebrates its 25th anniversary this month with a series of seminars on Samuel Beckett and Waiting For Godot at the University of Reading. Reading was where Beckett first spoke to me. I thought he was telling the truth. It was 1975 and I was reading Molloy not at Whiteknights or London Road but untutored on a bench in Prospect Park. I’d been offered a place on the postgraduate fine art course and I was new in town waiting to see a landlady. Beckett said:

I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now. I don’t know how I got there. Perhaps in an ambulance, certainly a vehicle of some kind. I was helped. I’d never have got there alone. There’s this man who comes every week. Perhaps I got here thanks to him. He says not. He gives me money and takes away the pages. So many pages…

I wasn’t a student of literature, I was an art student. In my innocence this first person narrative had me convinced I was reading an autobiographical confession. I had much to learn.

Beckett at 60 is just as well read as Beckett at 22 or as Beckett at 107. Happy Birthday to each of us, or maybe better say Happy Birthastrideofagraveday. Happy Days.

Beckett yes, Gormley never!

That seems a harsh judgement.

I can only refer you to the “Three Dialogues with George Duthuit”……..any page

Happy Birthday. Willem Defoe gave me a light for my cigarette at Riverside Studios…I remember that more than the play I went to see!

Thank you Sarah