We’d just walked up the hill out of the village and were about to turn off the main road to follow the Icknield Way. I’m pointing at the fingerpost, map in hand, but with such a weird posture, as if I don’t really know which way to go at all. This was the summer I discovered sciatica and every footstep was a conscious effort. But walking was so much better than sitting.

It was good to be on the move, on a recommended route – This is an excellent walk from the village of Wallington across the hills of north Hertfordshire along well-defined paths with wide open views across to Cambridgeshire.

“Come on, keep up!”

And there were indeed some great wide panoramic views.

But also lots of eye-catching flints underfoot, reminders of a previous walk in search of Henry Moore – Much Hadham & Much Moore. He loved their naturally sculptural forms but it’s hard now to find one that’s not been split by the plough. They’re fragments of potential Henry Moore maquettes.

A little further, at a break in the hedgerow, there’s a hollow tree with a box hidden inside. At a guess I’d say it’s a geocache left there to be found in a game of treasure hunt. I added a miniature Henry Moore to the prize.

And was there also a dried rosebud, tied with a label “for George”?

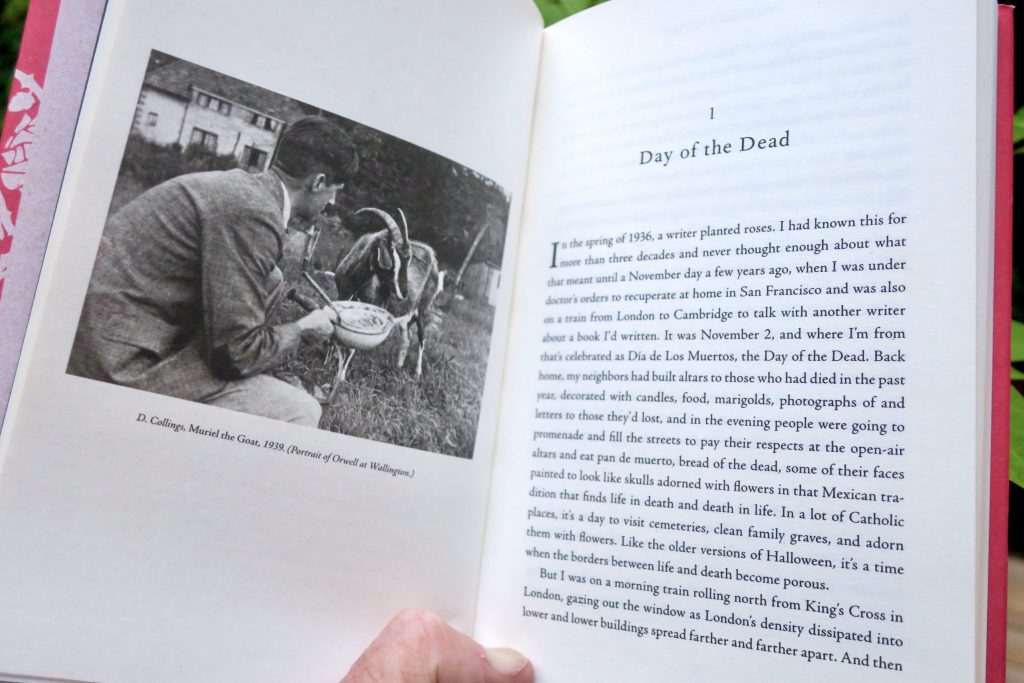

I’d recently been reading Orwell’s Roses, a fascinating book by Rebecca Solnit, with a resonant opening few pages that had me hooked from the beginning. She’s on a train from London to Cambridge, travelling through suburban north London, passing close by where I’m now sitting as I write these words. She’s on her way to meet an unnamed fellow writer, but I think I know who it is. It’s November 2, Día de Los Muertos, a day that we had commemorated for a good friend gone too soon – The Armada. And she mentions her friend, Sam Green, who I remember from his magnificent live documentary with Kronos Quartet at the Barbican – A Thousand Thoughts.

It all felt immediately familiar and I wanted to read more. She writes of how she and Sam have a shared love of trees, and an essay he introduced her to, A Good Word for the Vicar of Bray by George Orwell…

He proposes that “the planting of a tree, especially one of the long-living hardwood trees, is a gift which you can make to posterity at almost no cost and with almost no trouble, and if the tree takes root it will far outlive the visible effect of any of your other actions, good or evil.” And then he mentioned the inexpensive roses and fruit trees he had planted himself, ten years earlier, and how he had revisited them recently and in them beheld his own modest botanical contribution to posterity.

It felt like a good idea to visit Wallington, where George Orwell lived from 1936-40, and to walk the field paths and hedgerows round about. The book is a collection of stories about him, all woven intricately together, and it seems like the landscape might be a network of walks, each treading a lifeline, recounting a story, and I wonder if he walked these paths too.

And if he did would he have stuck to the designated paths, or would his wayward spirit have been up for an occasional trespass?

We kept to the straight and narrow.

More shapely flint shards, nestled in the stubble, watched us go by.

The public footpath becomes a permissive bridleway,

but luckily we have a couple of horses with us.

Welcome to Clothall, a group of discreet residencies, each hidden behind a high hedge, but united by a post box and a community noticeboard.

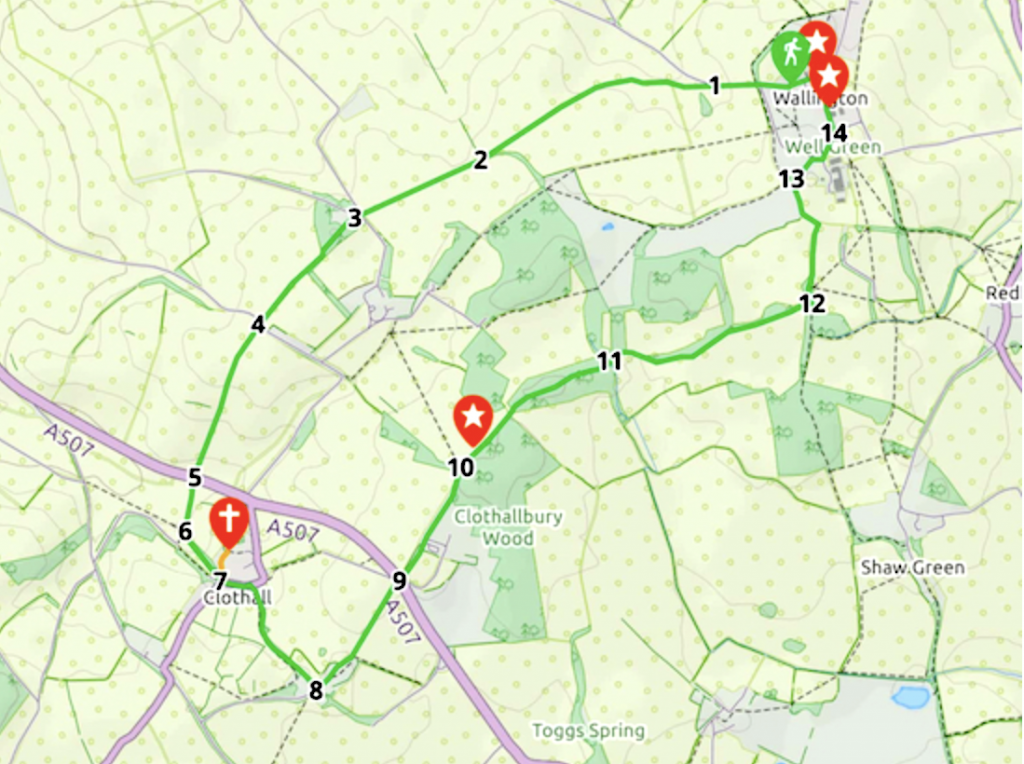

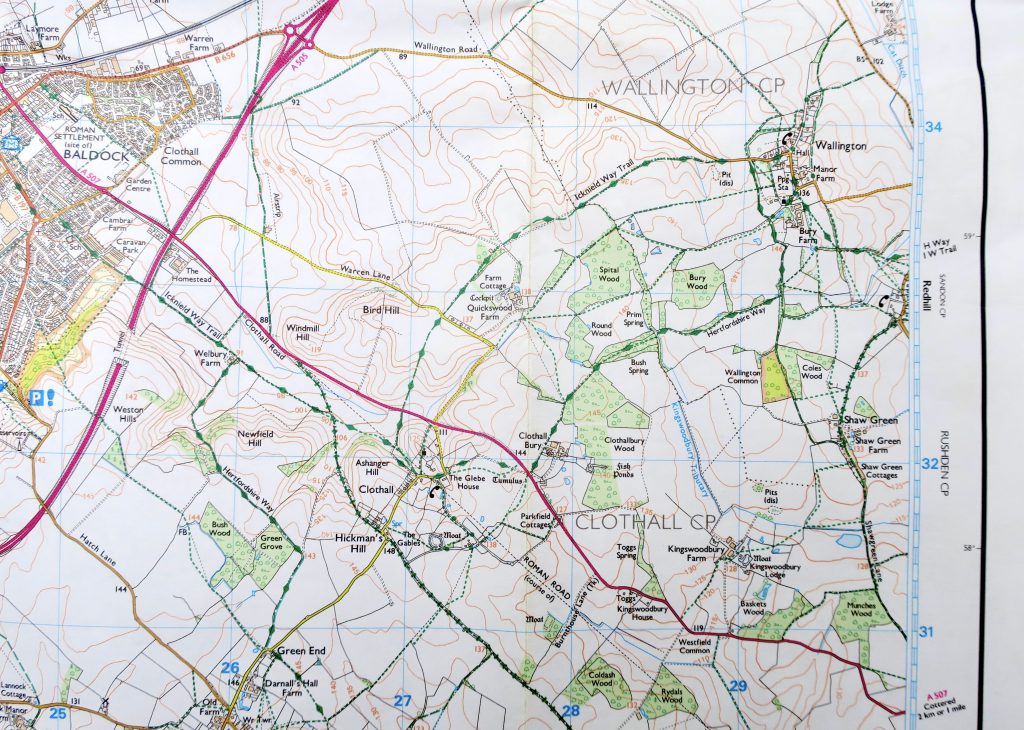

I was still carrying my OS map but I should’ve been looking at it. I’d also downloaded a map from the Hertfordshire Walker website. I should’ve been looking at that too, and reading its directions.

10: Ignore the footpath to the left and continue heading NE, still on Clothall footpath 9, with the ditch and Clothallbury Wood on your right, for 300m until you come to the end of the wood.

We were not paying attention and followed the footpath to the left, the one indicated by the great big arrow, through the middle of a field of barley.

I didn’t realise there was another path. The sign was so compelling. And the path was so inviting. Littered with more Moore maquettes than I’d ever seen together in one place. I was continually stooping to pick them up and, wincing with sciatica, I imagined a line of flint vertebrae laid out in a spinal column across the field (and a boot stamping on it – forever).

There’s a nicer account in Rebecca Solnit’s book of a walk along a similar path not far from here…

Other fields were bare and freshly plowed, and the pale chalky furrows were sown with flints. I had become captivated by this type of stone so unfamiliar to me when I had first come across it on Cambridgeshire walks with Rob Macfarlane in earlier years – with the black, blue, and white of them, with the way they curved like something organic, with the curious shapes, smooth surfaces, and razor-sharp edges. The flints in the fields between Baldock and Wallington were more beautiful than those I had seen before. Covetousness and curiosity seized hold of me, and I began stepping off the path to the edge of the fields, picking them up, discarding some, picking up some more, enraptured by the forms and the sense of so vast a quantity of them all around me.

Even after centuries of agriculture, they were thick on the ground. There were dozens every square metre, from chips and shards to big irregular lumps weighing several pounds. The latter resembled, at first glance, at least to my eye, small animals and large internal organs. They constituted a dictionary of flint possibilities and I was picking up a vocabulary of form from it. One was the shape of a large drumstick, glossy black on the inside, rough white on the outside. Others were shaped like cocks and balls, and some split-open lumps resembled small busts of human figures, at least to me, and I collected a little family group of anthropomorphic lumps with celestial blue or black faces.

The flints usually have a rough cement-textured whitish exterior that, like the outer layer of the brain’s cerebellum, is called a cortex, and on the inside they are smooth as glazed ceramic or glass. The interiors are white or black or any shade of an exquisite stormy blue gray, from pale to midnight, or a mix of these colors. They curve, and their shape is sometimes described as a nodule, but their sharpest edges are sharper than scalpels. Flint, like obsidian, was a stone of choice in the Stone Age. Around the nearby town of Hitchin, which in Orwell’s time had the Woolworth’s where he appears to have bought most of his sixpence roses, hundreds of Stone Age flint tools have been found.

Flints were formed when this landscape was the bottom of the ocean; they began as the sediment that filled the burrows in that ocean floor or that moved into the space left as sea creatures decayed: they often have biomorphic forms because they are in fact often casts of what life left behind. The chalk itself that gave the soil its pallor was the remnant shells of innumerable tiny sea creatures, and so if the landscape billowed and swelled like the deep sea perhaps it was because it had once been exactly that. So I swam leisurely across an ocean of flint and wheat, not quite certain I was on the right path until I hit a narrow hedge-flanked road across which huge white letters spelled out the word S L O W. It curved down to enter Wallington.

Rebecca Solnit: Orwell’s Roses

We were still some way from Wallington. Our wrong turn along the flint path had brought us to Quickswood Farm.

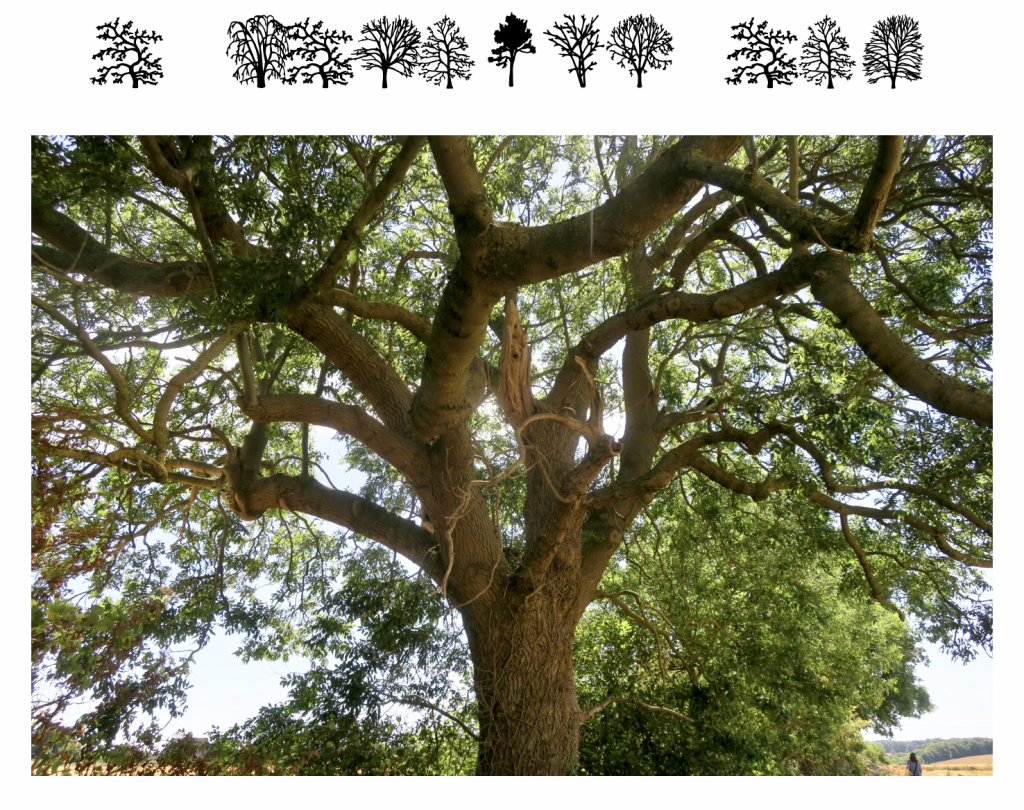

But a wrong turn worth taking to see the magnificent Quickswood Oak.

One day we’ll return and follow the path we should’ve taken (such a familiar refrain), but for now this is the way to go.

We came back into Wallington via the churchyard.

Flints and roses.

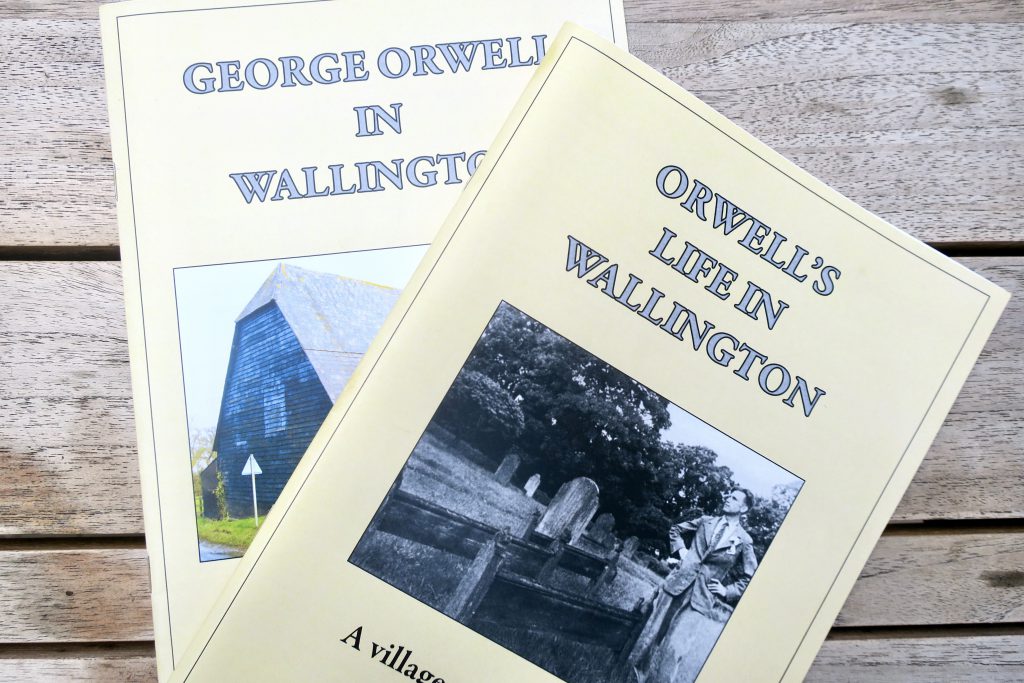

Inside St Mary’s Church we found a couple of useful pamphlets for sale.

Big Brother is watching you.

Eyes on the fence and a notice warning against fly tipping.

Wadlington!

A sign by the village duck pond.

A little further down The Street we come to The Great Barn of Manor Farm.

Mr Jones, of the Manor Farm, had locked the hen-houses for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes. With the ring of light from his lantern dancing from side to side he lurched across the yard, kicked off his boots at the back door, drew himself a last glass of beer from the barrel in the scullery, and made his way up to bed, where Mrs Jones was already snoring.

At the bottom of the hill stands a house formerly known as The Plough Inn.

Next to the pub in Kitts Lane stands ‘Monks Fitchett’, now restored and thatched as it would have been when first built, a vast improvement on the damp, tin roofed ‘Wallington Cash Stores’ that Eric Blair (George Orwell) first rented in 1936. On the bank opposite is the piece of ground where he had his allotment and kept some of his animals.

Dan Pinnock: Orwell’s Life In Wallington

We went back out to the garden, where even on that November day two big unruly rosebushes were in bloom, one with pale pink buds opening up a little and another with almost salmon flowers with a golden-yellow rim at the base of each petal. They were exuberantly alive, these allegedly octogenarian roses, living things planted by the living hand (and shovel work) of someone gone for most of their lifetime…

The apparent directness of these two plants’ connection to him and to that long-ago essay about roses and fruit trees and continuity and posterity filled me with joyous exaltation. So did the fact that this man most famous for his prescient scrutiny of totalitarianism and propaganda, for facing unpleasant facts, for a spare prose style and an unyielding political vision, had planted roses. That a socialist or a utilitarian or any pragmatist or practical person might plant fruit trees is not surprising: they have tangible economic value and produce the necessary good that is food even if they produce more than that. But to plant a rose – or in the case of this garden he resuscitated in 1936, seven roses early on and more later – can mean so many things…

Rebecca Solnit: Orwell’s Roses

This revelation comes at the beginning of the book. Orwell’s reputation as a miserablist is suddenly re-evaluated. His love of roses shows him in a new light, offering a meditation on pleasure, beauty, and joy as acts of resistance. It’s a good place to review his journey and the perfect starting point for a country walk. There are lots of paths, it hardly matters which you follow.

※

※

Hertfordshire Walker: Walk 127

So evocative of many walks I have made with eyes on the ground in search of Moore flints. Rarely succeed in spotting one. Many years ago I visited a Moore exhibition where there was a long glass topped case filled with flints Henry Moore had collected, many drawn on by him as he saw echoes of the human figure. Magic. Rebecca Solnit’s book WANDERLUST a history of walking is a book I often return to.

I have enjoyed reading these stories. Thank you!

Great post! This was helpful for me on my recent trip to Wallington to visit the Orwell sites! I spotted some of the flint stones and it was great to have some context for what they are thanks to your post.