Selborne was the perfect rendezvous, being halfway between London and Salisbury. We came down and Howard Phipps came up and we met in the middle, in a field just off Gracious Street, the car park of the Gilbert White Museum, where we transferred the contents of Howard’s car boot to ours, in preparation for his exhibition in the Rowley Gallery window. But not before a lovely sunny walk around the outskirts of the village. And this map, embedded in the vicarage wall, dated 2 June 1953, is as old as I am.

I was intrigued to read one of the captions: Gilbert White, probably the most famous of English naturalists, and author of The Natural History & Antiquities of Selborne was born at the vicarage in 1720… All his observations in natural history were made in this village, and his famous book was written in the house in which he died. And then this curious sentence: His experiments with echoes were carried out in King’s Field. What did that mean? Elsewhere, via the magic of the internet, I found a further reference (thanks to Robert Hardy in The Classical World, published by The John Hopkins University Press):

I remembered a series of paintings I made years ago called Echo’s Bones. I’d pinched the title from a poem by Samuel Beckett who was also inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I too had had a thing for echoes and reflections, for one thing and another. But I digress.

Come on! Get a move on!

Alas, we never got to King’s Field and its echoes, but now everywhere I look there’s one thing and its other thing, first sight and recognition, seeing and believing, visions and the light through the leaves, looking back at us.

Church Meadow and The Lythes

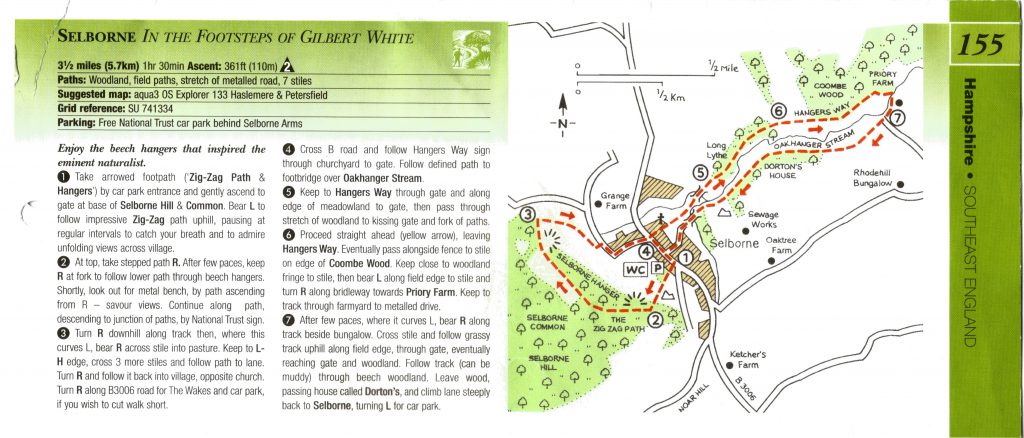

Another map, but this one is overlaid with a crazed laminate of alternative routes. A map and its echo, a pause for reflection, a momentary diversion.

These are some notes which I took in November 1983, trying to capture these characteristics in the jumble of damp closes and copses that lies between the church and the Lythes, one of Gilbert’s favourite walks:

No real views or prospects – except momentarily glimpsed through the trees, and framed in a gap at the end of the valley. What you do see is much more a matter of close-up detail and texture: layered freestone; tree-roots contoured round the layers; fungus on the dying trees, saplings in the gaps left by fallen trunks, yet these textured too – bent, opportunist, twiggy, eaten, snapped, re-shooting. Beyond the trees, broken, tufty grass, surrounded by more woods; dips in the ground; tiny coppices in further dips just visible by the tops of their winter twigs; glimpses of water – in ruts, pools, winding drainage ditches, but mostly invisible until you are close by, hidden by trees and tussocks; the water broken up, too – shelves of gravel in the streamlets, bays, cattle wallows, loops and islets, fallen trees bridging the water and entangled with the hedges.

Richard Mabey: Gilbert White, A Biography

We come down Church Meadow beneath a great oak tree growing alongside Oakhanger Stream. Howard is trying to recall the last time he was here, but it’s our first visit. Sue leads the way whilst I skip off down into the stream.

The Lythes are the woods on the steep slopes of the valley, overhanging our path. Elsewhere they’re known as hangers. First we enter Short Lythe and then Long Lythe, but I can’t see the join, it’s just one long bucolic dream of dappled light and deep green breaths. It’s all about the magical lie’the land.

N A T I O N A L T R U

I ought to have been more observant. I later read a description from the National Trust – Between the Short and Long Lythes (two steep banks of ‘hanging’ beech and ash woodland on your left) is a small grassy coombe on your left and a small meadow on your right.

Past the iron bench, along the Long Lythe, the ground opens out on your right into a long thin and rough meadow, developing where a poplar plantation has been removed.

We cross a wide meadow down to the water where the path leads us between two large ponds, likely vestigial fishponds of the medieval Selborne Priory.

Pike tile excavated at Selborne Priory – This floor tile relates to the story of Richard, Bishop of Chichester, who blessed the fish pond on a day when they were catching nothing – and a three-foot long pike was immediately netted!

We came along Hangers Way by Coombe Wood and crossed the stream at Priory Farm. We passed between outbuildings and antique machinery around the hairpin of our route to head back along the valley to Selborne.

The path takes us into the woods again where we walk beneath towering beech trees through leaf-filtered light. Walking and talking in leaf light.

Walking words and talking hands.

Shadows and light in black and white.

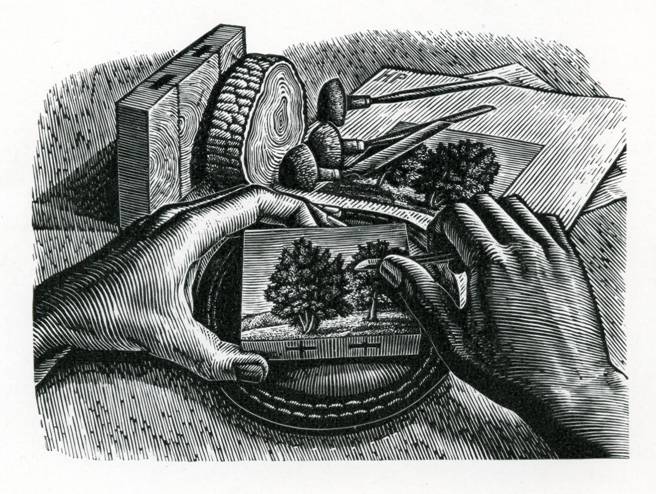

Boxwood Engraving

an echo of its woodblock.

We climb the hill to a standstill, caught in our tracks as we stop and stare a tall beech up and down, from top to bottom, from leaf to branch to trunk.

And beyond. Sliding down the steep bank to the stream, under a redundant out-of-reach rope swing, and below the exposed roots. They have grown to engulf another iron bench, strategically placed against the tree, one of many similar benches encountered around our route.

Funny how this tree got singled out for attention, beside the path, above the stream, tied with a rope, appointed with a bench. Maybe in pre-Covid days this was a turnaround trysting tree, a playground, an outdoor gym.

A sunken wreck

Wood and stone, sycamore and chalk

Picture and frame

Back in the village again we lingered awhile, we followed the one-way system through the Selborne Arms and kept our distance in its garden, before following the Zig-Zag path up Selborne Hill.

It’s a narrow side-to-side vertical climb up the face of the hill, a hand-cut switchback up the hanger, a corniche planted with hedges and occasional belvederes, a slow labyrinth of day-trippers come for the view.

Echo’s Bones

asylum under my tread all this day

their muffled revels as the flesh falls

breaking without fear or favour wind

the gantelope of sense and nonsense run

taken by the maggots for what they are

Samuel Beckett 1935

The fossil-shells of this district, and sorts of stone, such as have fallen within my observation, must not be passed over in silence… ‘Cornua Ammonis’ are very common about this village. As we were cutting an inclining path up the Hanger, the labourers found them frequently on that steep, just under the soil, in the chalk, and of considerable size.

Gilbert White: Letter III, The Natural History of Selborne

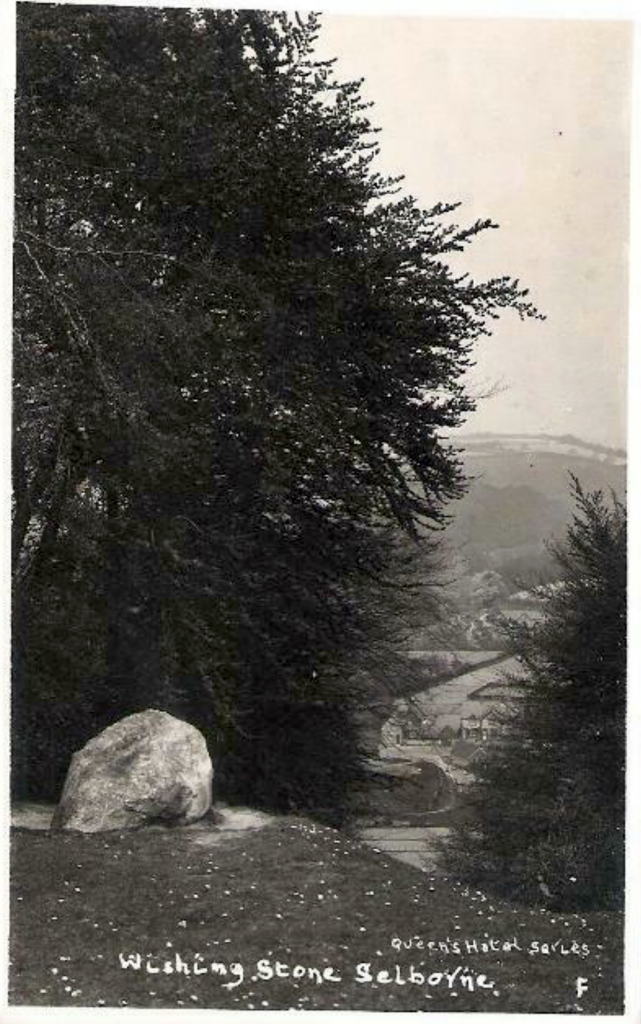

There is a grand view at the top.

And beside the path a large white sarsen named the Wishing Stone. I’d have taken a photo but it was occupied by a cheerless fellow who observed the view and exclaimed “Why?” His wife looked to the path and said, “Shall we go on?” He heaved a sigh, “We may as well, we’ll be dead soon enough.”

Hereafter a stroll through the woods and a spectacular arboreal lightshow.

The light through the leaves and the shadows on the ground.

The high part to the south-west consists of a vast hill of chalk, rising three hundred feet above the village; and is divided into a sheep down, the high wood, and a long hanging wood called the Hanger. The covert of this eminence is altogether beech, the most lovely of all forest trees, whether we consider its smooth rind or bark, its glossy foliage, or graceful pendulous boughs.

Gilbert White: Letter I, The Natural History of Selborne

And it’s all a dance of shadows and light.

I’d sing the song if I knew the words.

This way and that way and this way and that way.

We finished up at the Gilbert White Museum, too late to enter, it was about to close, but just in time for tea and cakes, and a few souvenirs from the brewery to help me practice my Zig-Zag walk when I got home.

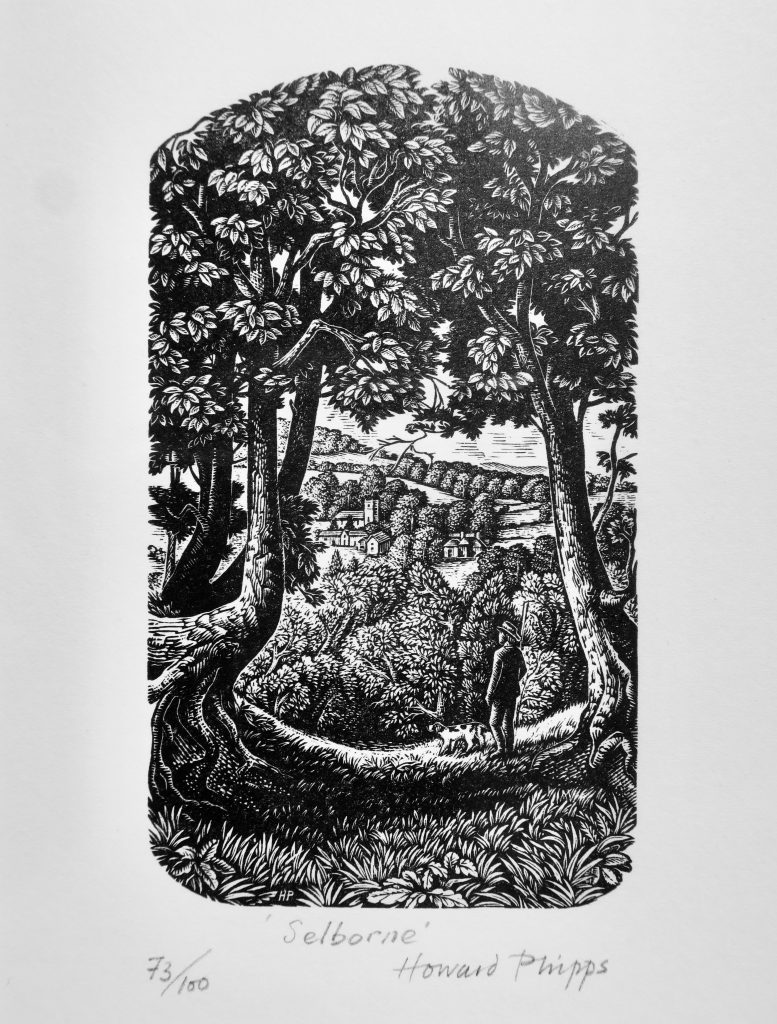

But best of all, a souvenir from Howard.

※

Howard Phipps / The Rowley Gallery

※

※

Open Country / The Dorset Coast

I find it delightful, but frightening, that I should waken at 4, check email (which I do rarely these days) and find a Rowley Gallery blog post announced. “Lovely! Great way to start the day,” I say to the sleeping dog and remove the book that had fallen from me at midnight. It is a used Penguin I’d found online, saving shipping from the UK, and time, that most precious commodity. For, after listening to Melissa Harrison’s wonderful podcasts, I wanted quickly to read all of Gilbert White I could. I was on p.13 and had drifted to sleep wondering about his observation of “freestone” and shells, taking the sea life and the geology into a single grasp, and relishing the rest of Selborne before me. And we have a Freestone a few miles from me, here near San Francisco, and what does it actually mean? But on to the Rowley posting! I knew there might be trees, but then Phipps, too? On Twitter there had just been Phipps’ Malacombe Bottom posted by Henry Rothwell…and now here was one of Selborne? Well, too much, maybe magical. I won’t go into the great Copper Beech at Eggleston Hall Gardens, but it’s a fine one, if you’ve not seen it. Thanks so much for the post!

That’s fantastic! Thanks Pat. I love a good coincidence.

A beautiful blog. Quite by chance and another coincidence, We are going to Pallant House on Tuesday to see an exhibition about Gilbert White and the artists. The blog has whetted my appetite. Thank you Chris. Frames of Reference has become an Art work in its own right. Long may it continue.

Thanks Paul, that’s great, I had no idea about the Pallant House exhibition. It looks very tempting – Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists. Though they should’ve included Howard too!

always good to be here again with your trilling words and luminescent photographs….I particularly liked the 3 section mighty tree…and who could not cast a smile on a bench absorbed by a trunk….Hello! hellloo! Hello! hellooo!