The original city of Noto was 12km further up the valley of the Asinaro River from where present day Noto now stands. It was relocated after the devastating earthquake of 1693. The original site is now an overgrown ruin, reclaimed by nature and slowly sinking back into the earth. There were buildings here from the 17th century and all down the ages back to Greek antiquity, but now they’re mostly just stones in the undergrowth, but for one or two exceptional and magnificent survivors.

The most beautiful road from Noto to Noto Antica leads uphill to the left from the public gardens, crossing Noto Alta and passing through the village of San Corrado di Fuori, with attractive early 20th-century houses. Outside the town is the verdant Valle dei Miracoli, home to the hermitage of San Corrado Confalonieri, who lived here in the 14th century. The 18th-century sanctuary contains a painting of the saint by Sebastiano Conca.

The road north from San Corrado continues across a beautiful upland plain with old olive trees. It then descends to cross a bridge decorated with four obelisks. The byroad for Noto Antica is lined with early 20th-century Stations of the Cross on the approach to the large sanctuary of Santa Maria della Scala, next to a seminary with an elegant facade surmounted by three statues and a balcony.

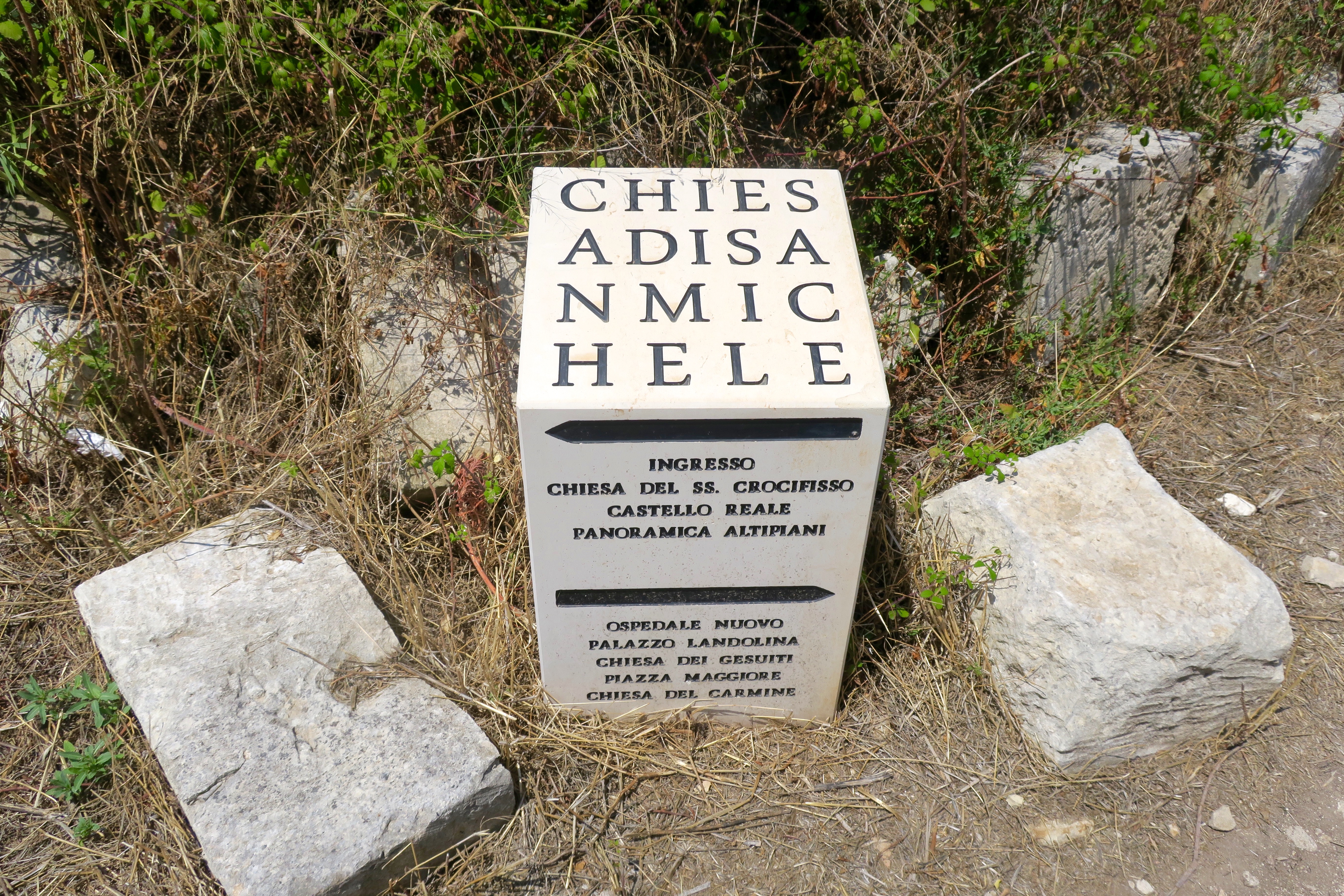

The road now descends to cross another bridge over a ravine before reaching Noto Antica, abandoned since the earthquake of 1693 and now utterly deserted. The scant ruins, reduced to rubble and overgrown, are very romantic, and provide inspiration for artists, photographers and writers. The settlement here long antedates its legendary foundation by the Sicel chief Ducetius in 448 BC, and was the only Sicilian town to resist the depredations of Verres (governor of Sicily and notorious art thief). The entrance is through the monumental Porta della Montagna, with remains of the high walls on either side. A rough road leads up past a round tower and along the ridge of the hill. The conspicuous wall on the left belonged to the Chiesa Madre. After 1km, beside a little monument, the right fork continues to end beside the Eremo della Madonna, a small deserted chapel, with a good view of the surrounding countryside.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

As we wandered around the site our attention was drawn to various notices, imperfectly translated into English, pointing out the remains of historic buildings, sometimes no more than a pile of stones.

Chiesa del SS. Crocifisso

(sec. XI)

The Norman structure (early XI century) went through radical changes at the end of the fifteenth century, with the construction of new chapels, on one of which it was based the magnificent bell tower. Here it was venerated an ancient wooden crucifix.

Castello Reale

(secc. XI-XVII)

Started in 1091 by Duke Giordano, son of Roger of Altavilla, it was boosted in 1430 by Duke Peter of Aragon, modernised in 1545 under Charles V, and finally, in 1675 it was provided with guns during the Franco-Spanish war.

The entrance to the round tower was closed off with a metal grille, but I was able to look through with my camera, and I could just make out some intriguing carvings and inscriptions on the left-hand wall.

Chiesa di San Michele

And then, quite by chance, I discovered more graffiti on a stone wall below the tower. It was a rich palimpsest, one drawing upon another in a confusion of marks, hard to discern an identifiable image but I thought I saw a ship and maybe a fish. And there’s a figure carved into a niche that looks like it might have been done yesterday. But somehow I don’t think so. It feels altogether pretty ancient.

It’s such a privilege to find these here. I’m more used to looking at work like this in a museum or maybe a church, but never outdoors. And then the next stones are covered with ships of all different sizes – zoom in on the photo below for a closer look. It was only later that I learned this place was once a prison and these are the marks made by its inmates: their petrified dreams of freedom.

As we go on I find myself checking the rocks for handmade marks.

Mostly though it’s hot and cold, wet and dry, shadow and light.

But the handbuilt walls are something else!

Chiesa dell’Ospedale Nuovo

(S. Maria di Loreto)

The new Hospital, along with the small church, was built in mid-sixteenth century, in place of the ancient Hospice of the pilgrims; in 1653 it was entrusted by the Senate of the city to the care of the Fatebenefratelli Fathers of S. John of God.

A rock shelter, temporary refuge from the midday sun.

Palazzo Landolina di Belludia

(sec. XVII)

The most magnificent noble baroque palace in the city, was built in the early decades of the seventeenth century. The portal was surmounted by a large rounded balcony, supported by a winged quadriga. There was carved the Latin motto: Magni spes altera Olympi.

Chiesa e Collegio dei Gesuiti

(sec. XVII)

Founded in 1606 with the funds devoted for that purpose by Baron Charles Giavanti, the superb monumental Baroque complex that stretched for more than 60mts., was built in about 20 years, designed by the Jesuit architect Natale Masuccio from Malta.

Area della Piazza Maggiore

(Impianto medievale)

It was situated at the centre of the city and on it many important monuments (such as the Mother Chu… and the S… ce) we… To… eenth… no…

(This notice, apparently in sympathy with that which it described, was almost completely worn away.)

At the crossroads we hesitated, then instinctively turned right and walked blindly for a while through the trees, enjoying their dappled shade. As the path descended we realised we must be leaving the precincts of Noto Antica. A young couple passed us, walking so determinedly in the opposite direction that we became convinced we were going the wrong way, and so we turned back and returned to the Piazza. In retrospect I wish we’d continued down the hill…

A great walk is one that you can take down to the river below (Cava de Paradiso). It is a zigzag path from the past that reaches a kind of earthly paradise where the Asinaro River… between one waterfall and another, runs alongside other remains from the past. One above all: the ancient local tannery, carved into the rock.

But instead, we headed off in the opposite direction, following the second-most shady path.

The path ended at a collection of abandoned farm buildings and a great view of the valley beyond.

An ancient carob tree.

Chiesa del Carmine

(sec. XVII)

Founded by the Carmelites at the end of the sixteenth century, in the Pastuchera district (south-eastern outskirts of the town), on the site of the ancient little church of S. Martino, it was completed about in 1660 and it resulted among the most beautiful and spacious churches in the town. Its designer is unknown.

Little now remains of the church, but for this plan marked out with a few of the surviving stones.

We returned to the entrance, and briefly explored a few of the wayside caves we’d missed earlier.

We’d seen very few other visitors but the car park was surprisingly full.

Over the road an inviting limestone path led up into the hills.

But it was time to go.

This olive tree, pitted with hollows, was a sign of things to come.

We drove away along the narrow, single-track road above the ravine, and all along the hillside was perforated with hollows, a necropolis of ancient shrines. Over the coming days, as we explored more places, we began to imagine the whole island must be carved with similar handmade perforations.