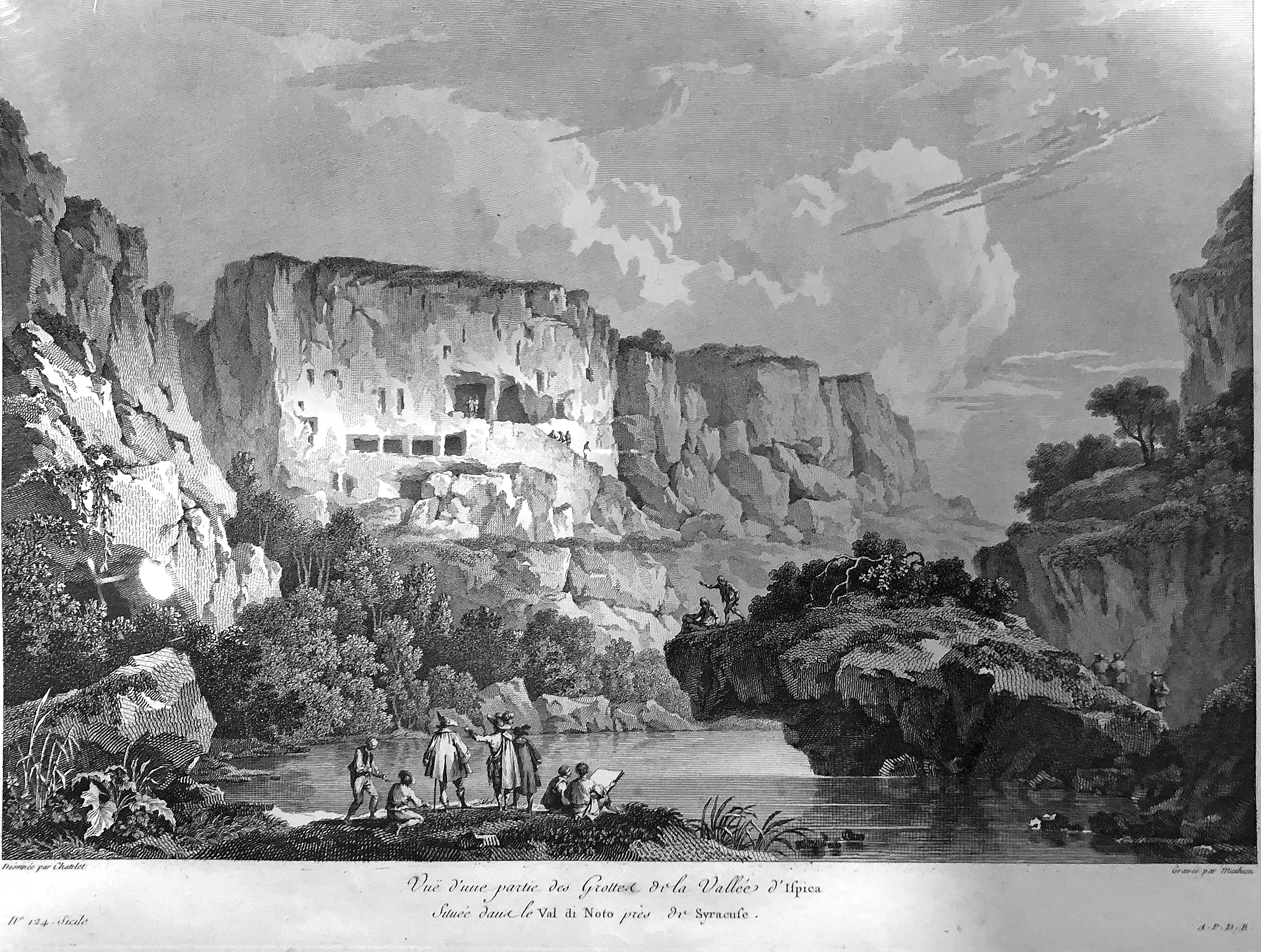

It was midday when we arrived in Ispica, the August sun was high and the streets were hot but the town was closed, the shutters were down and lunch was off the menu. It appeared unwelcoming but the guide book had promised much more – The small town of Ispica was rebuilt on its present site after the earthquake of 1693 destroyed the former town on the valley floor… The chalk eminence on which it stands is pierced with tombs and cave dwellings. These can best be seen in the Parco della Forza at the south end of the Cava d’Ispica… best approached from Ispica along Via Cavagrande. It has lush vegetation, water-cisterns, tombs and churches, all carved out of the rock, and a remarkable tunnel known as the Centoscale (‘Hundred Stairs’), 60m long, formerly used by people carrying water from the river to the town.

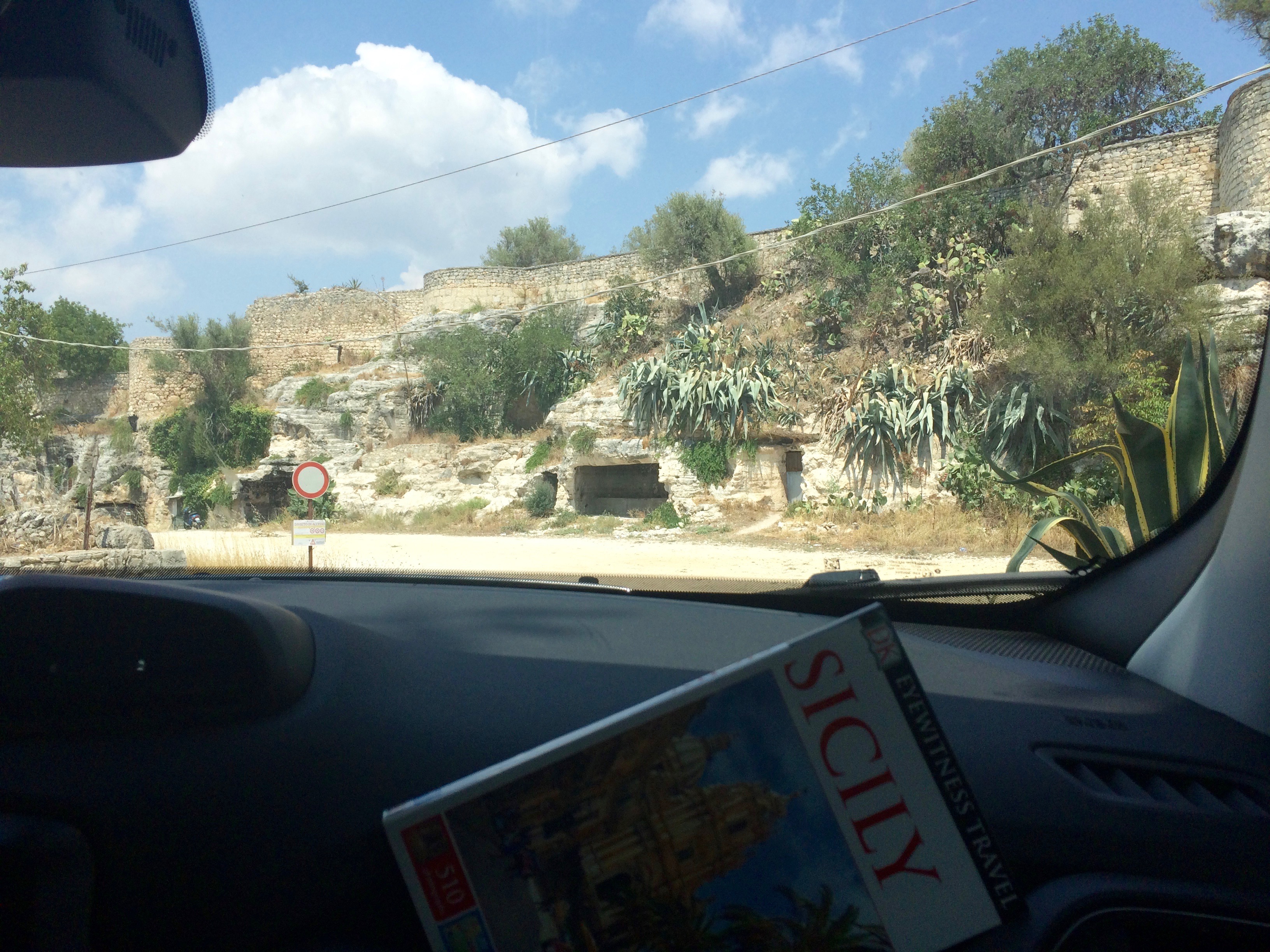

The path from the town descends steeply into the valley

beneath tombs and cave dwellings

to the rock-carved chapel of Santa Maria della Cava.

The path becomes a dried-up riverbed.

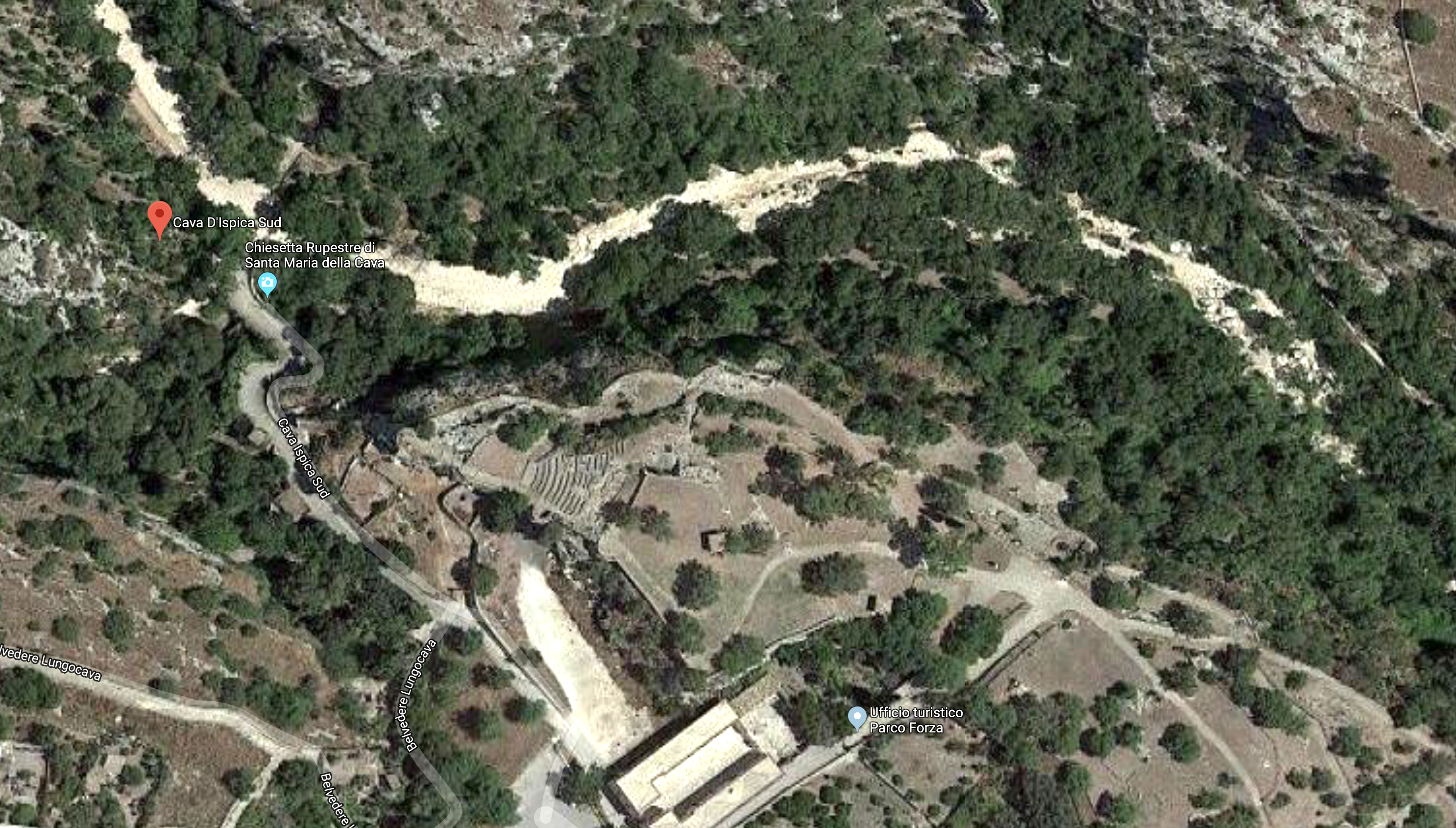

Afterwards I looked on Google Maps and I was surprised to see what looked like the terraces of an ancient amphitheatre above us. It was not apparent from the path, and nor was the tourist office!

This was the gateway to the Cava d’Ispica, a deep gorge winding 13km up into the hills towards Modica, but the Parco della Forza, designed to introduce and celebrate it, was nowhere to be seen.

We continued ahead

into the canyon

but without a map and with no signs to guide us

we simply followed the path

to where someone had been shelling almonds.

We might have walked all the way to Modica. But not in this heat.

The path led to an isolated farm, and a sudden overwhelming barking of dogs.

It was not a welcoming sound. We turned and retraced our steps.

Sue pursued by a swallowtail butterfly.

A circle of almond shells and a Fiat 500.

A distant view of Ispica.

The cool shade of walnut trees.

Lo Stagli

Il Compost

This was the Parco della Forza, overlooked earlier, now discovered abandoned.

Until recently a proud resort with its own website – Cava d’Ispica.

Pomegranate

Prickly pear

It was too hot to linger so we made an air-conditioned escape down the road to Modica.

There we got lost but then saw a sign and felt suddenly at home.

Modica is made of chocolate.

During the 16th century, cocoa beans imported from Mexico by the Cabrera family were made into chocolate by the confectioners of Modica, using the ancient Aztec method of slowly grinding the beans between two stones to avoid overheating, and then adding maize. Elsewhere in Europe the method of manufacture evolved rapidly to industrialise the product, improve the flavour and lower the cost. In Modica, however, the method is still basically the same, the only difference being that sugar instead of maize is added towards the end of the grinding operation, giving a typical grainy consistency to the finished product. Natural flavourings are also added, such as cinnamon, vanilla, orange essence or chilli pepper.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

The Cioccolato di Modica (“Chocolate of Modica”, also known as cioccolata modicana) is an Italian P.G.I. specialty chocolate, typical of the municipality of Modica in Sicily, characterized by an ancient and original recipe using manual grinding (rather than conching) which gives the chocolate a peculiar grainy texture and aromatic flavour. The specialty, inspired by the Aztec original recipe for Xocolatl, was introduced in the County of Modica by the Spaniards, during their domination in southern Italy. Since 2009 a festival named “Chocobarocco” is held every year in the city.

Cioccolato di Modica / Wikipedia

When the Spanish were ruling Sicily in the 16th Century, conquistadors went to Mexico and brought back cacao and the recipes needed for what the Aztecs called xocoàtl, a paste ground by a smooth round stone called a metate. Unlike the often over-sugared and creamy snack we know as chocolate, the original xocoàtl was bitter and used to enhance sauces for meat dishes, grated over salads or eaten on its own as a dietary supplement. If prepared with certain spices, it was considered an aphrodisiac.

In Modica, generations of families have followed the same techniques, using metates crafted with lava stone from Mt Etna. Locals would mix the chocolate paste with sugar, “cold working” it so that the sugar doesn’t get hot enough to melt; it gives the treat an unusual but deliciously crunchy texture. Then, they would incorporate flavours typically enjoyed on Sicily such as lime oil or pistachio. Today, flavourings are occasionally adapted to more modern tastes such as the current European fashion for sea salt chocolate.

The Italian Town with an Ancient Secret: Lucinda Hawksley

We climbed up from the wide main street of Modica Bassa through tiny alleys and courtyards of acacia and bougainvillea to the terraces of Modica Alta and the spectacular church of San Giorgio.

The imposing church of San Giorgio, built from the 11th century-1848, is mostly the work of local stonemasons, directed later by the architect Paolo Labisi and dedicated to the patron saint of Monica Alta. It is reached from Corso Garibaldi, which runs parallel to Corso Umberto. Some 250 steps (completed in 1834) ascend to the church, built in pale honey-coloured stone. The facade is one of the most remarkable Baroque works in Italy.

Blue Guide Sicily: Ellen Grady

San Giorgio e Il Drago: Costantino Carasi