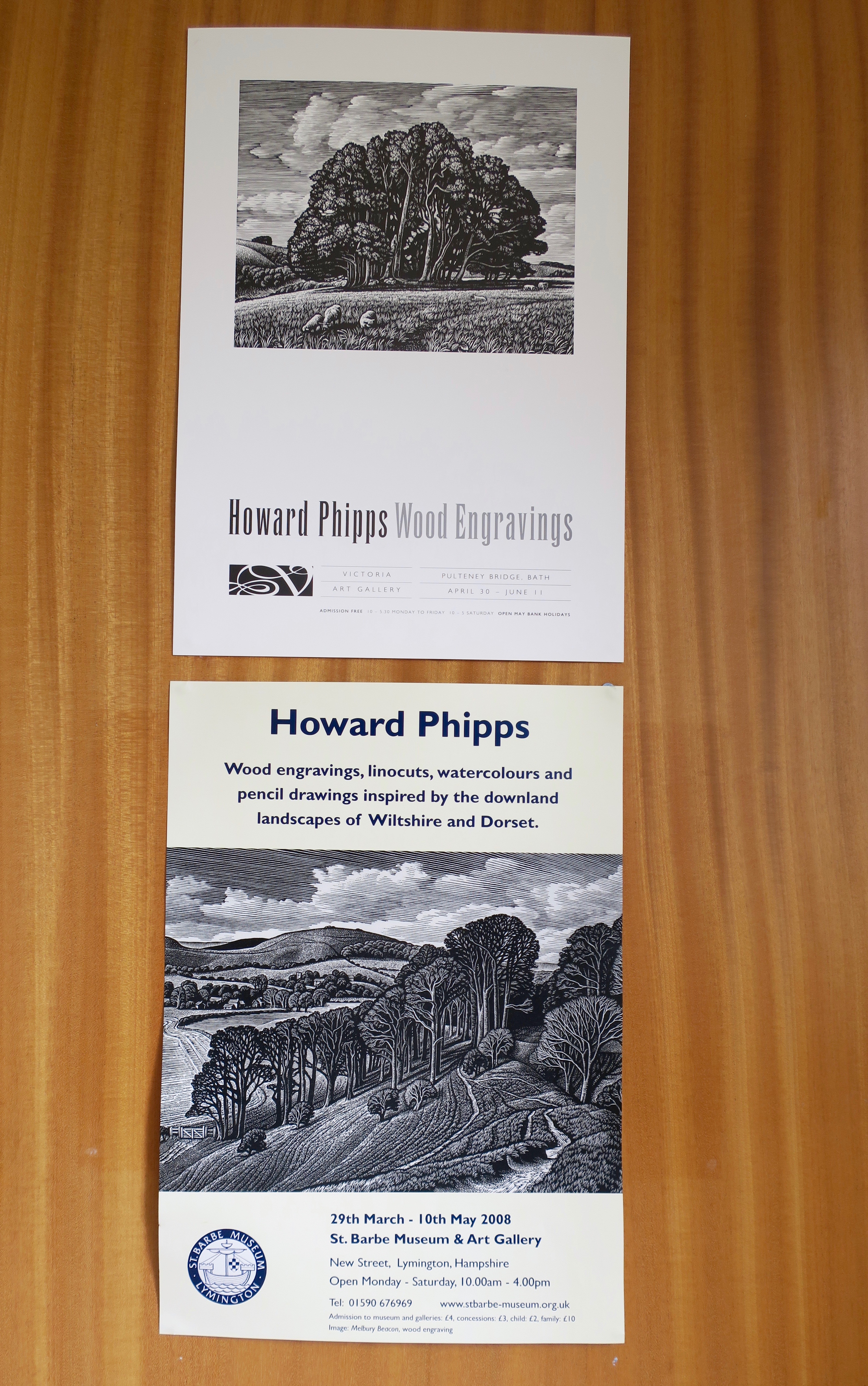

I’d been looking forward to this for years. Ever since we first had his wood engravings I’d been curious about where they came from. We usually get Howard’s prints in the post or occasionally he might bring us a few, but this time I was invited to go and collect some myself. It was an opportunity to visit his studio, to see how his wood engravings are made and also to discover the landscape that informs them. I left the A303 and followed the A30 down a dead straight Roman road to Stockbridge then along the old drover’s road towards Salisbury. I began to recognise the distinctive local features, the gentle rolling hills, the trees silhouetted against the sky, and I knew I was entering Phipps country.

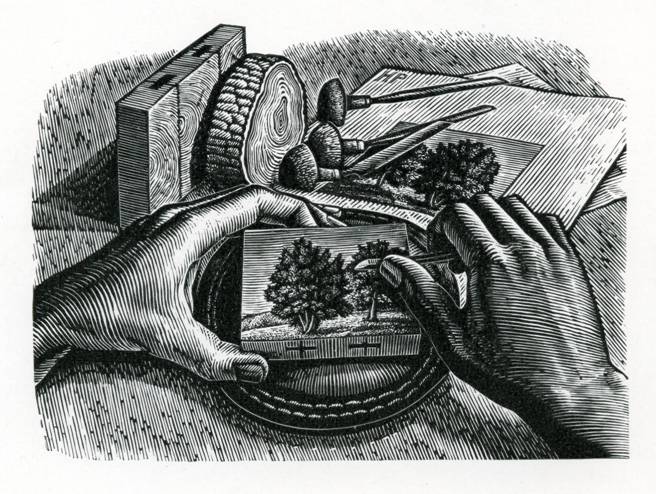

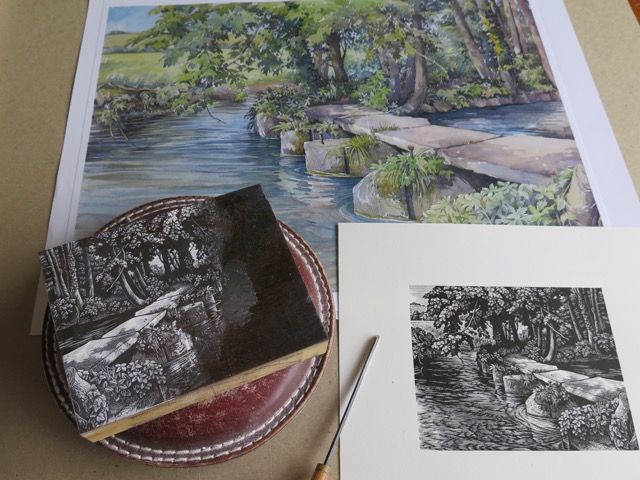

I learned that an idea for an engraving begins first with a drawing, then more drawings,

then the subject is explored further with watercolours and sometimes with oil paint.

When he’s engraving a boxwood block Howard refers to both drawing and painting,

but reflected in a mirror by his workbench so he can see the image in reverse.

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique, a development of the woodcut block, which was first used in Europe in the early fifteenth century to produce illustrative decorations, or single- sheet printed works. Woodcuts were made by cutting the soft side grain of a plank with knives and gouges, leaving the design, which was to receive the ink, in relief. With the invention of moveable type woodcuts could be used to illustrate books, as each could be inked at the same time. The art of wood engraving was invented in Britain in the late eighteenth century, and developed by Thomas Bewick of Newcastle. By engraving on end-grain hardwood such as boxwood, with tools comparable to those used by engravers of metal, it enabled artists to create finer images.

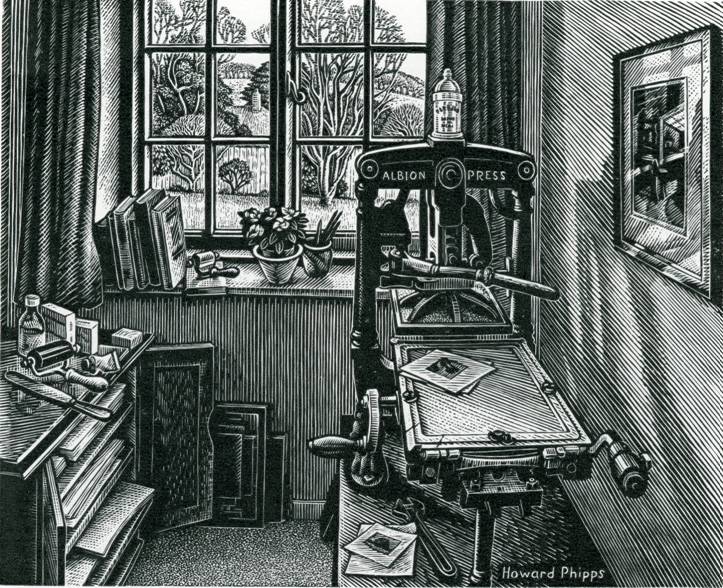

‘Boxwood Engraving’ [above] by Howard Phipps shows the artist engraving a block which is placed on a leather sandbag. The boxwood ‘round’ [top centre] shows an end grain slice with bark still on it, whilst adjacent to it is a prepared block made up of three jointed pieces. The burin-like tools used to engrave the mirror smooth blocks have intriguing names such as spitsticker, bullsticker, and tint tool; these make possible a wide range of linear and textural marks that will appear as white against the black uncut areas when the relief surface is rolled with ink and then printed. Wood engravers usually darken the block prior to engraving, as the engraved areas expose the light yellow colour of the boxwood; they are effectively drawing with light, whereas in a drawing dark marks are usually made on white paper. On completion the surface of the engraved block is inked with a roller, and pressure is applied in this instance using an Albion hand press, dating from the Victorian period [1862] .

The Print Room

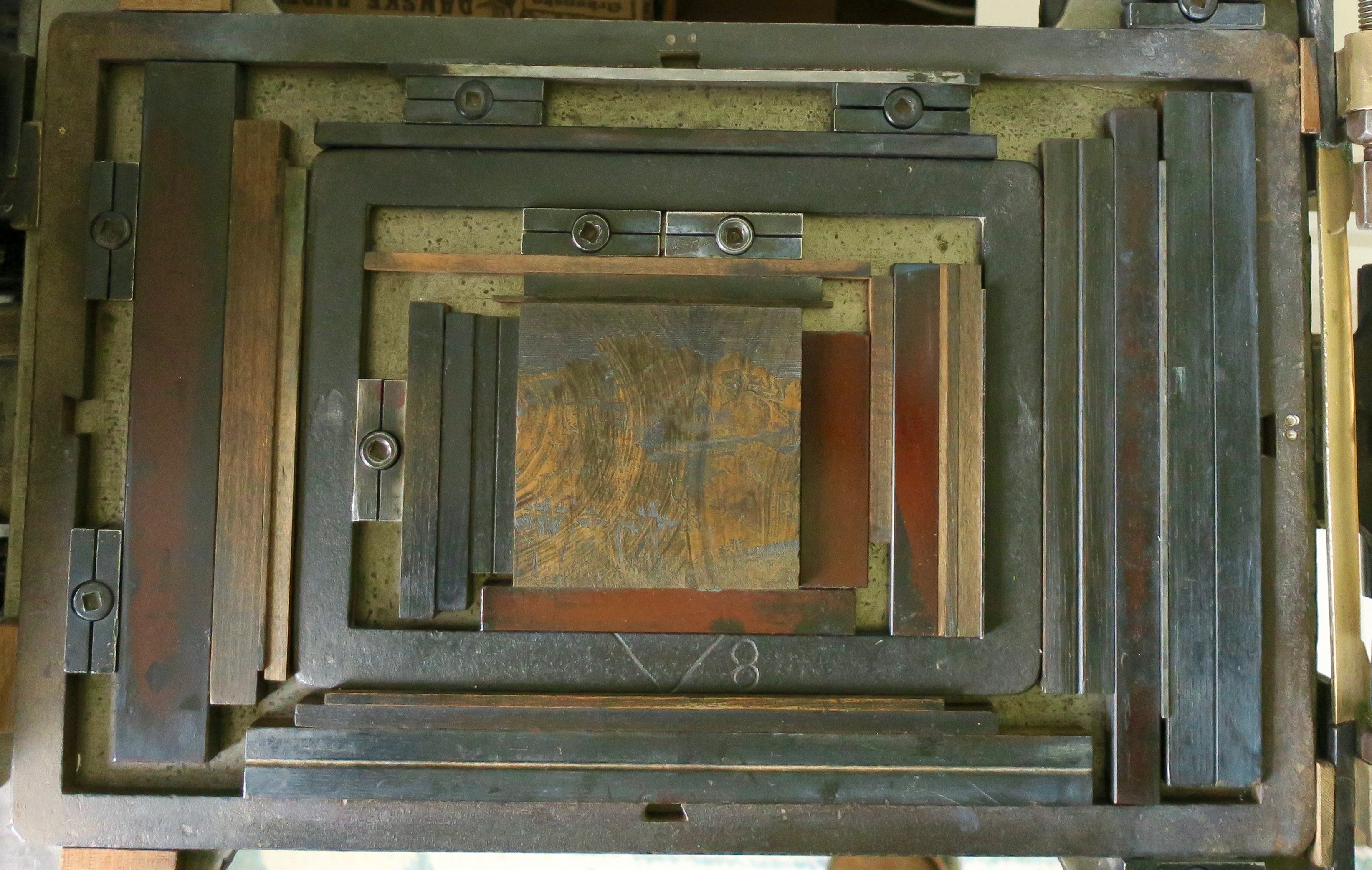

An engraved block on the bed of the printing press.

Flint and lichen on an old brick wall near the parish church at Bishopstone where we began our walk.

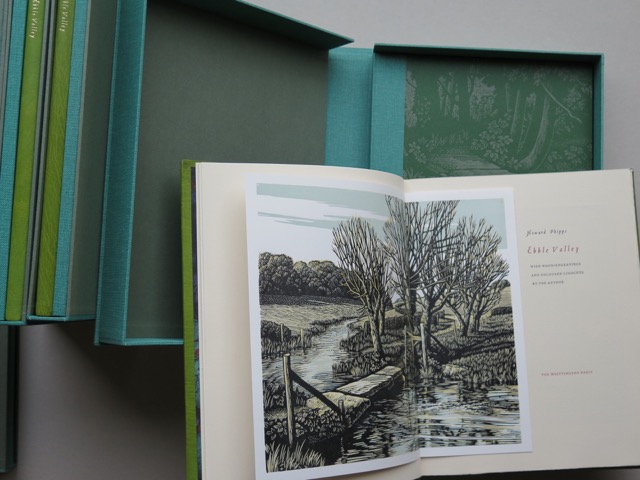

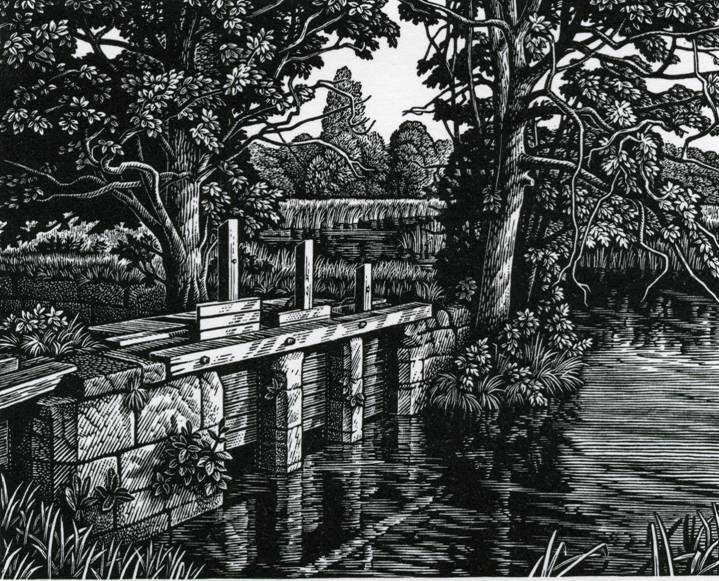

The River Ebble is one of the five rivers of Salisbury, a clear chalk stream of constant temperature.

On cold winter mornings, water vapour from the relatively warm stream

condenses in the cold air above to form fog.

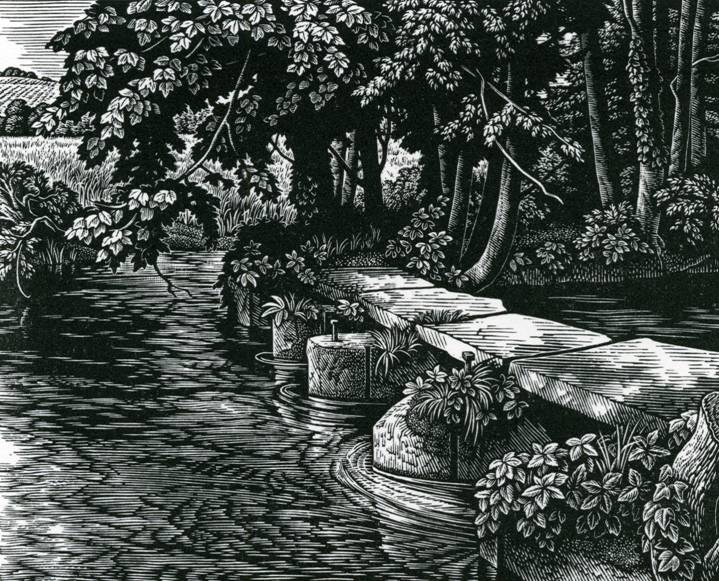

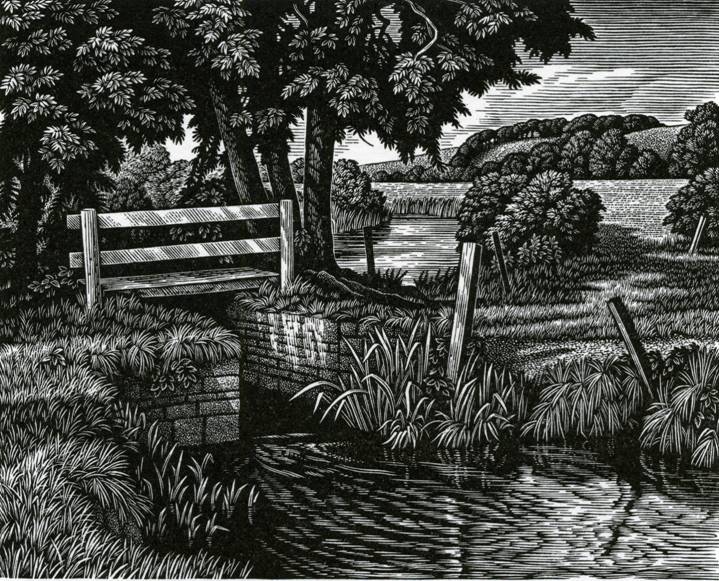

The Footbridge At Bishopstone

Wooden shutters slotted between the piers of the bridge were once used to control the flow of water.

It was the inspiration for Ebble Valley, a book of Howard’s linocuts and wood engravings.

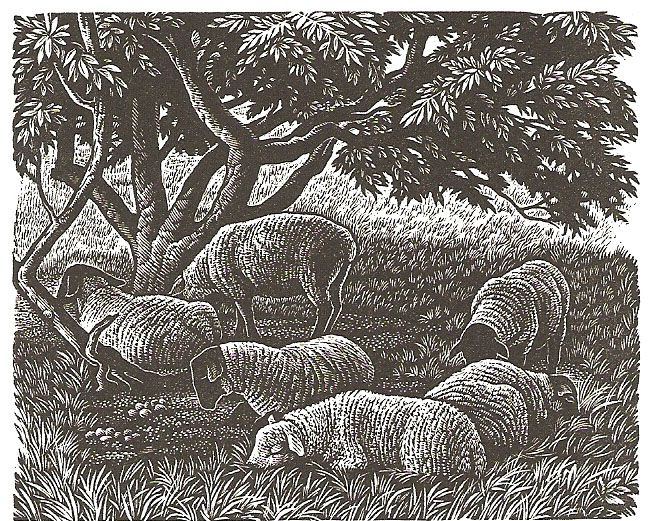

We followed the river downstream through meadows and sheep pasture

before climbing steeply up onto the chalk downland of Throope Hill.

Noon Day Shade

A spectacular view of a distant poppy field.

We continued along the path, climbing higher with the sound of skylarks above us, until before too long we branched off and descended into a great coombe, like a sheltering bowl in the hills, with the outlines of ancient strip lynchets just visible on the opposite flank. We passed a solitary walnut tree in its own little hollow and a buzzard circled overhead.

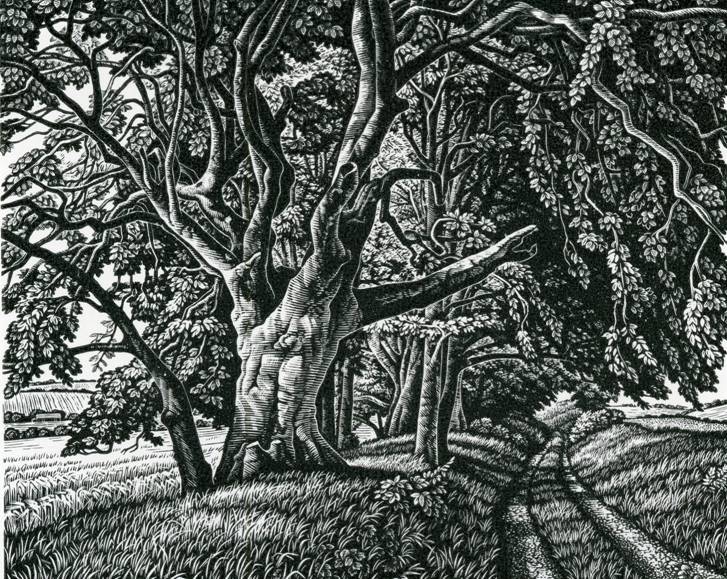

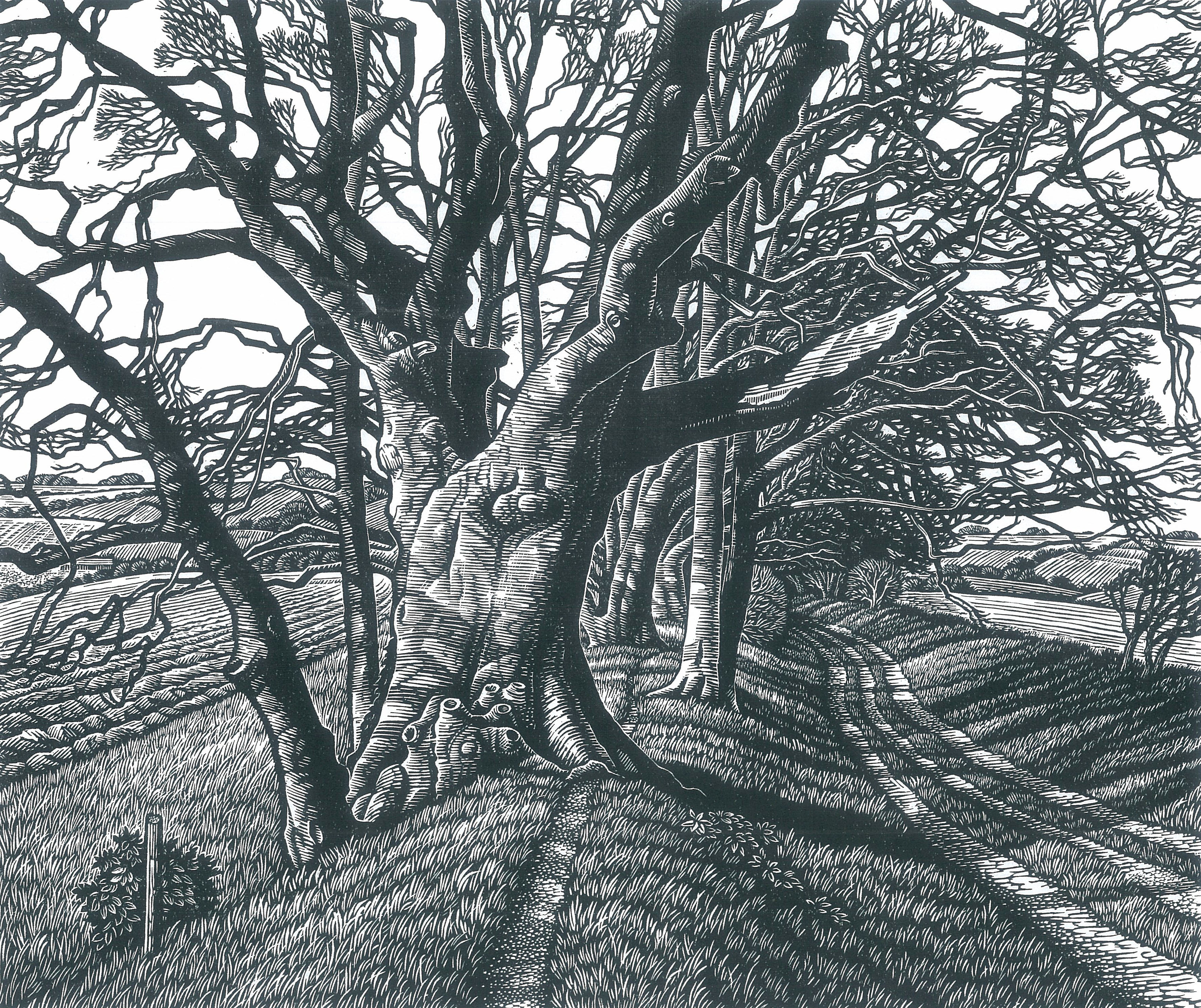

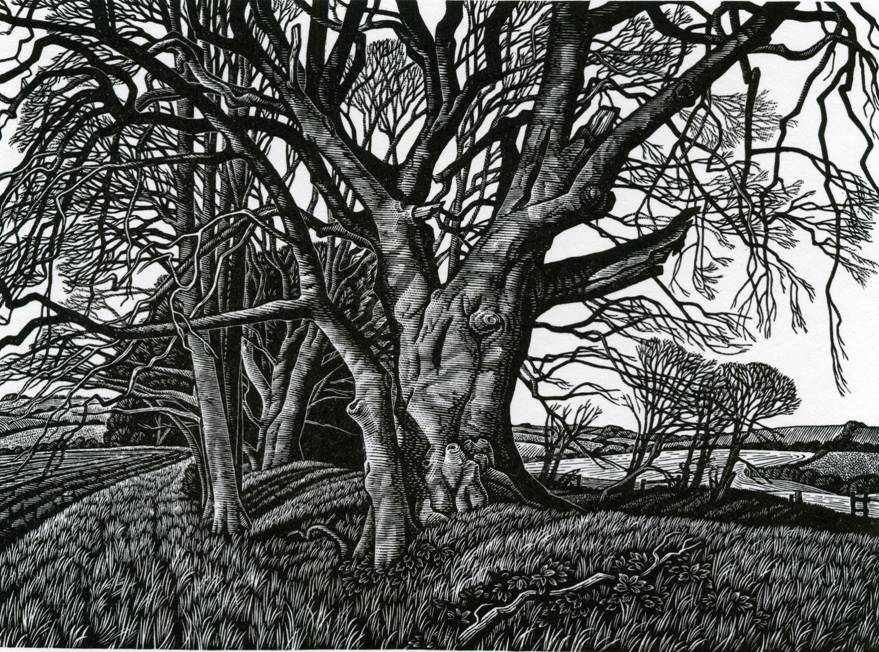

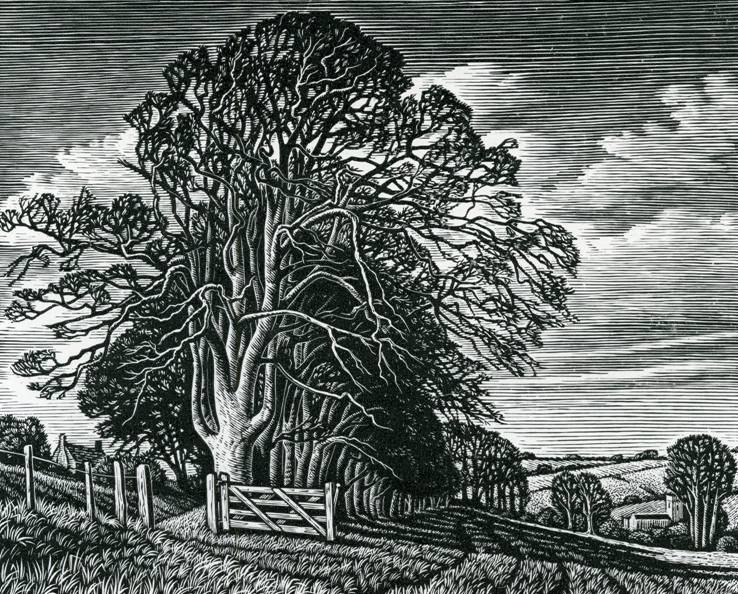

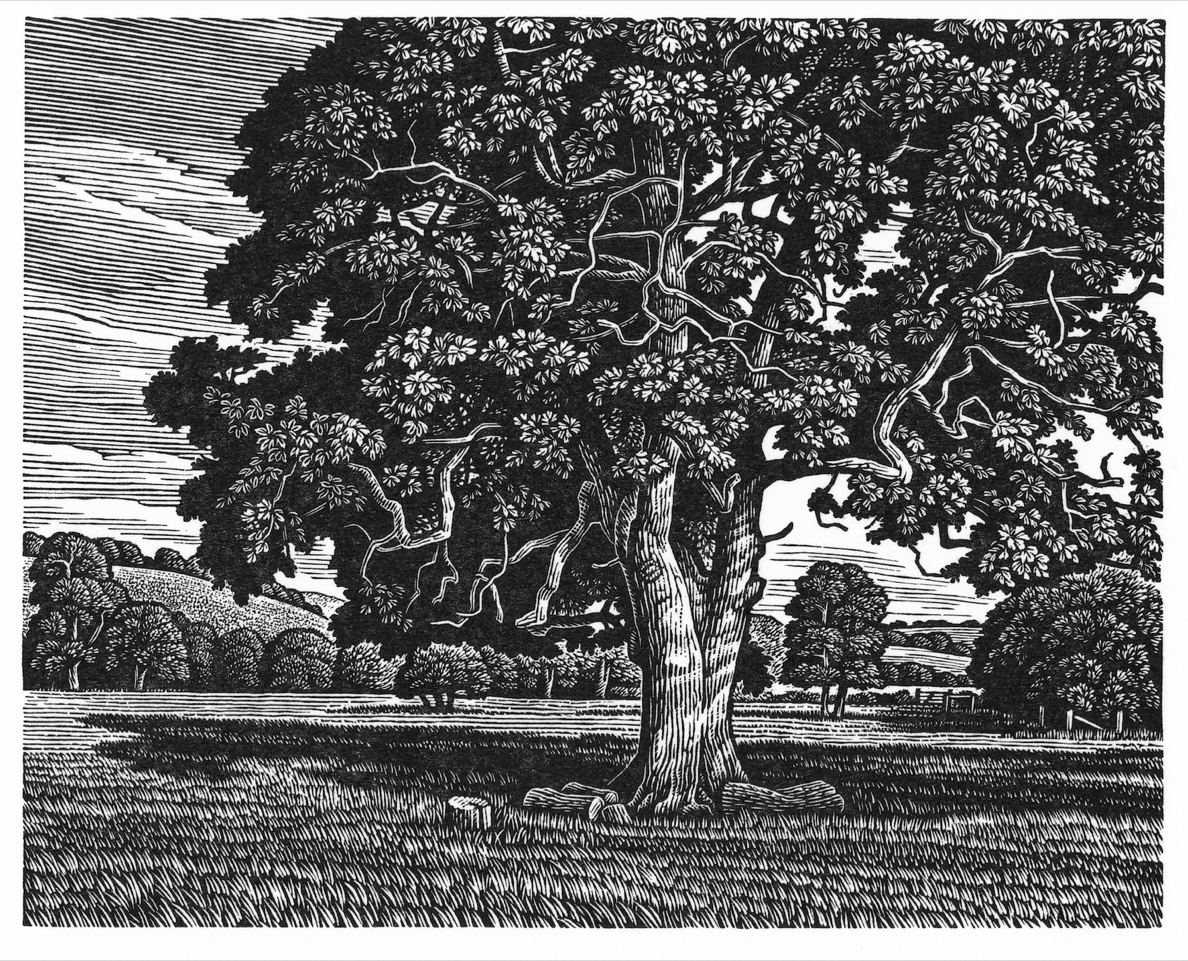

We came up onto another track along the next ridge, beneath a line of old beech trees.

These are some of Howard’s favourite trees and recurring subjects for wood engravings and linocuts.

Ox Drove

Beech Tree Cloister

Ox Drove in Winter

I’m not sure if he’s drawn this one yet. Maybe he’s thinking about it.

The field alongside was the one we’d seen earlier, from across the valley.

A crop of rape seed overwhelmed by scarlet poppies.

Back along the lane again and Howard recalled how one day as he sat here drawing this tree, a fox came to drink from the hollow cups at its roots. It seemed unthreatened by his presence because he sat there so still. Then later a rabbit came screaming down the lane, hotly pursued by a weasel, which took one look at Howard and gave up the chase, and the rabbit escaped to run another day.

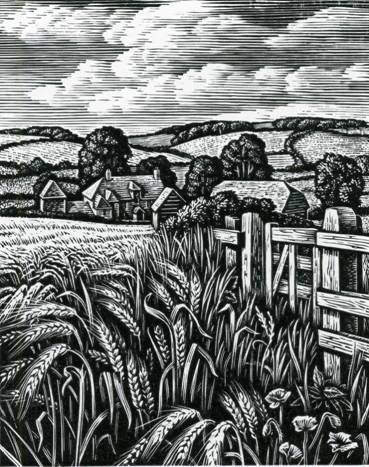

As we came down the hill, out from the hollow lane and through a field of wheat,

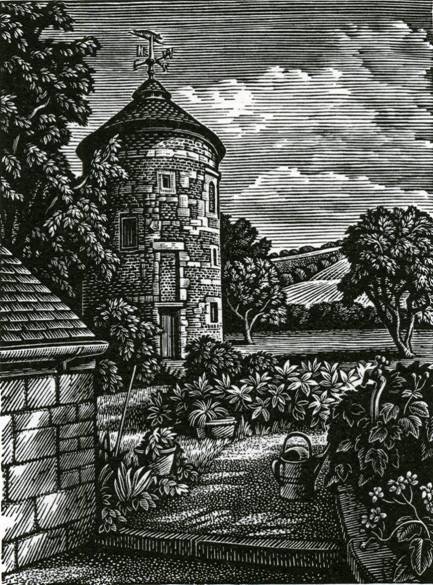

we spied a distant stone tower topped off with a dovecot and a weathervane.

Faulston Tower

We walked alongside the River Ebble. The sluice gates reminded me of others further downstream.

Salisbury Water Meadows

This wonderful old beech overhanging the river looks like a tree in need of a rope swing!

Back at the studio Howard showed me some of his preliminary drawings of beech trees.

Then I loaded a precious cargo of souvenirs, wood engravings cut direct from the Wiltshire landscape.

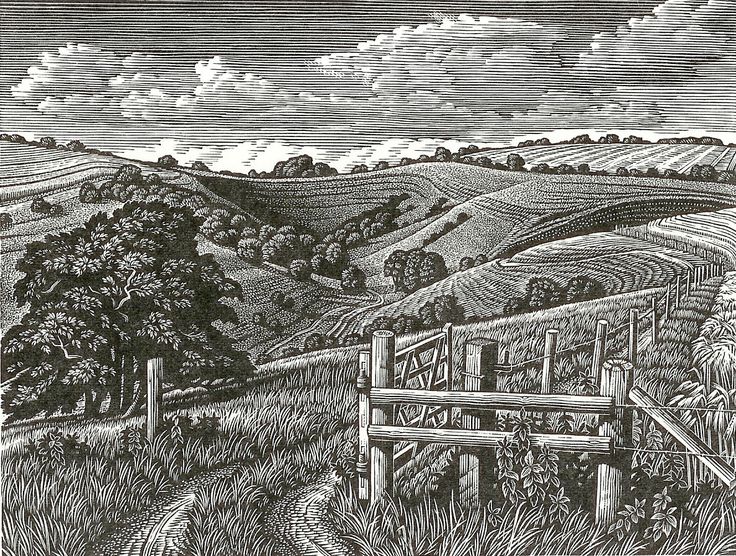

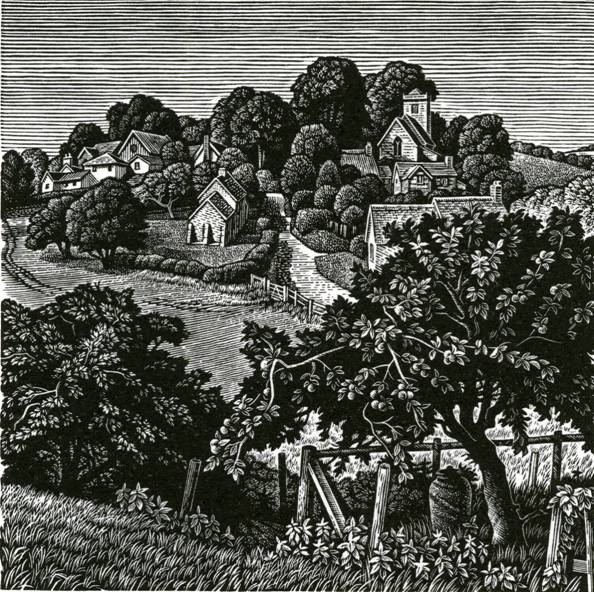

Knowle Hill, Broadchalke

Ebbesbourne Wake

Homington Water Meadows

Summer Fields, The Ebble Valley

Leaving the village I lingered on the bridge and watched the river flow away beneath the trees. There was an ancient cottage in a nest of scaffolding and ladders, its newly thatched roof almost completed. It felt like a corner of paradise. In my mind’s eye I retraced our walk and I fancied we’d followed in the footsteps of earlier artists – Samuel Palmer, Eric Ravilious, Robin Tanner.

Howard Phipps walks and draws and distills this slow-grown, long-cultivated landscape into carefully wrought wood engravings of great skill and dedication, that capture its essential solitude and beauty.

※

See more of his work at The Rowley Gallery.

※

PS: Update June 2017, a new engraving just arrived in the gallery, Ebble Valley Oak,

another reminder of our walk, and it’s included in this year’s Royal Academy Summer Exhibition.

Completely captivating. What a great trip Chris, and a treat to be in Howard’s studio and walk along with him in that landscape.

This is a very interesting article with great backstory to the beautiful prints.

Howard is a master of topography; he marvelously illustrates contour changes, showing grade changes between valleys and hills from different vantage points. His trees are pretty good too. Thanks also for the explanation about engraving on boxwood.