A couple of weeks before our walk around Burnham Beeches, I walked to Wittenham Clumps with Andrew Walton. We’d done the same walk five years earlier and afterwards Andrew had painted this little watercolour as a memento, here brightening up my sad old workshop wall. That was in the days before this blog; now I was keen to retrace our steps and record them for Frames of Reference.

I met Andrew at his house in Oxford, where he’d been working on paintings for a new collaboration with the poet David Attwooll, based on their walks together around the wetlands of Otmoor, an RSPB nature reserve to the east of the city. But today I was interrupting his researches and taking Andrew and another friend, the philosopher Jonathan Rée, to Oxfordshire’s most popular Iron Age hill fort.

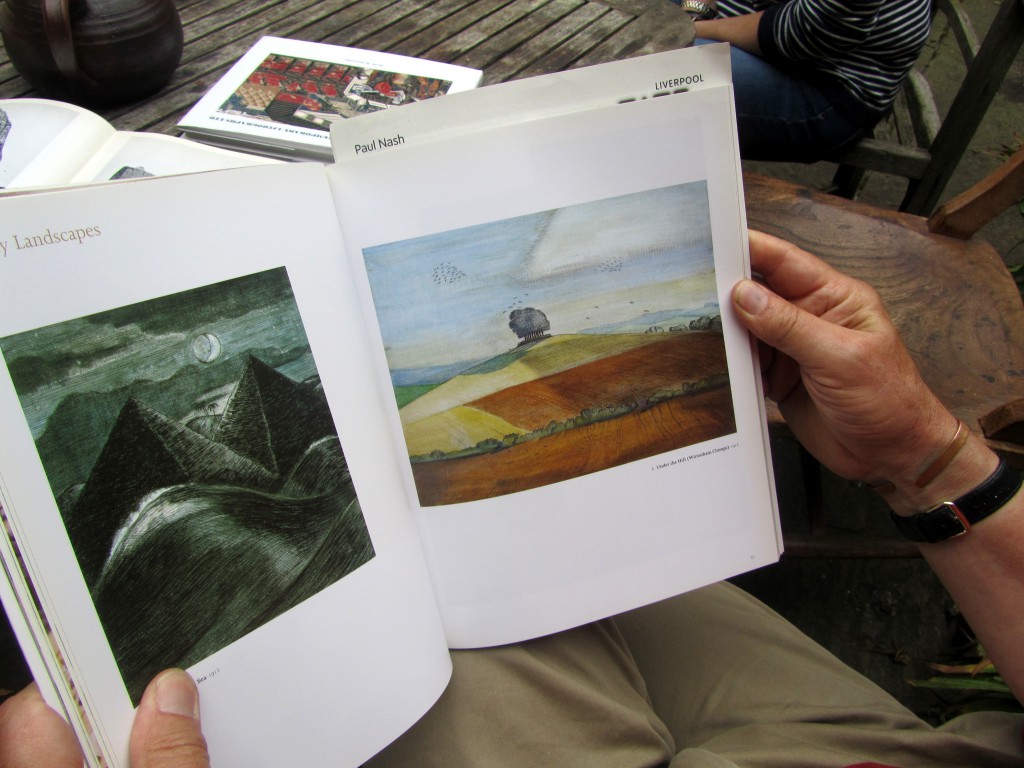

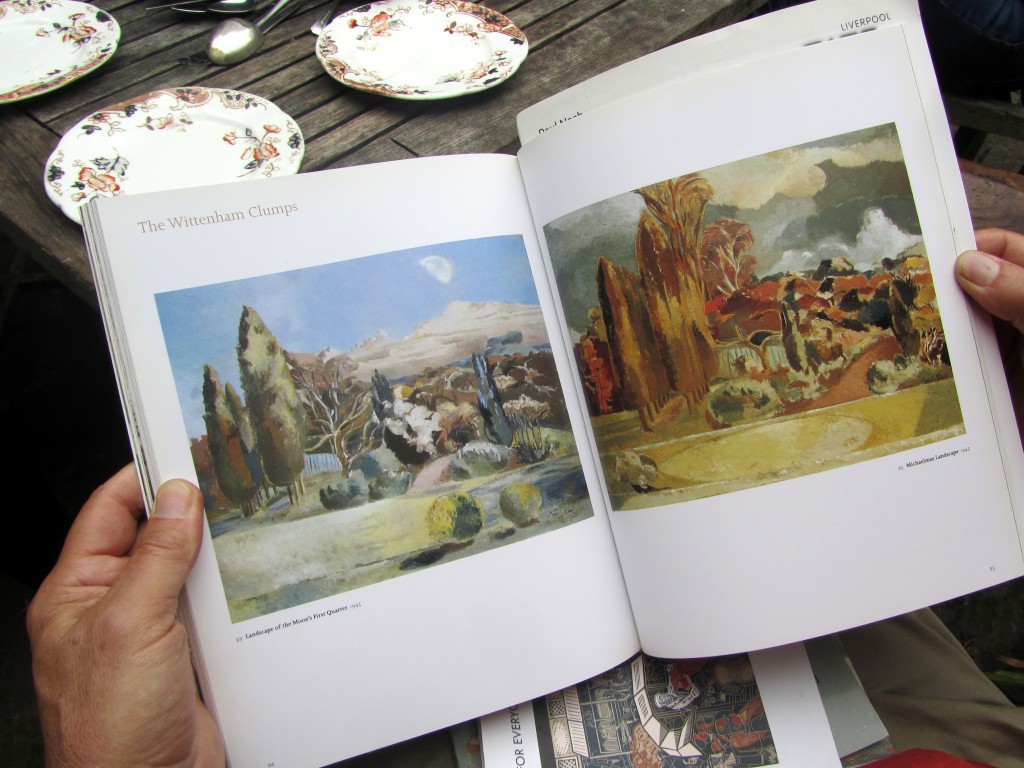

Wittenham Clumps was also a favourite place for Paul Nash. Between 1912 and 1946 he painted them repeatedly. Their magic inspired him to become an artist and he revisited many times during his life.

I am going to Wallingford in Berkshire next month and there hope to find some fine things, those wonderful Downs and wild woods down by the river. I have haunted them often and now I am going to try and interpret some of their secrets – Paul Nash, 1912.

His uncle lived at Sinodun House near Wallingford, in what was then Berkshire but is now Oxfordshire. The name Wittenham Clumps refers to the wooded summits of the hills more properly known as the Sinodun Hills. The two clumps of beech trees which crown both hills are the oldest known planted hilltop beeches in England, dating back over 250 years.

Wittenham Clumps also inspired this painting by Andrew Walton.

※

We began our walk at Dorchester-on-Thames, the same place we’d started from five years ago. Until then I’d always thought Dorchester was in Dorset. Dorchester-on-Thames, despite its name, is not directly on the River Thames but on the River Thame, just before the confluence of the two rivers.

Dorchester Abbey was built on the site of a Saxon cathedral. It’s a church with a rich heritage…

The Iron Age fort on Wittenham Clumps dominates a landscape settled since remotest antiquity. To the south, in the Berkshire Downs, is Churn Nob, and here, in 635AD the missionary Bishop Birinus, sent from Rome by Pope Honorius I, preached to Cynegils, King of Wessex. To the north, enclosed between the River Thames and its tributary the River Thame, lies Dorchester, a small village with a great Abbey, a cradle of English Christianity. The building we now see was begun in the 12th century, replacing two earlier Saxon cathedrals (some Saxon fabric is still evident in the north wall of the nave). The Norman building expanded in the 13th century and was richly aggrandised in the early 14th century when the chancel was added with its wonderful window sculpted with the Tree of Jesse, its stained glass and its exquisite sedilia. The great tower, rebuilt in 1602, but incorporating a 14th century spiral staircase, rises above a lush landscape of willows and flowering water meadows. On this site, perhaps in the Thame itself, Birinus baptised King Cynegils, with Oswald King of Northumbria standing godfather.

It’s a beautiful church. I love its variety of spaces, some elaborately decorated, some just left empty. I wouldn’t have been surprised to find animals stabled here too. There are remains of wall paintings in the People’s Chapel; a 14th century crucifixion scene with the Virgin Mary on the left and St John on the right and the sun and moon overhead, and above it in the arch there’s another crucifixion, this one presumably earlier, abstract, minimal, reduced, elegant in its beautiful simplicity.

In the Shrine Chapel we found this knight in armour, identified by his postcard as William de Valance. The twisting movement of the sculpted figure made it a favourite of Henry Moore.

William de Valence, d.1282. One of the finest late C13th funerary effigies in Britain.

Alongside him rests a much more conventional recumbent knight.

The Jesse window in the chancel, its divisions formed by a Tree of Jesse, depicts how Christ was descended from King David’s ancestor Jesse, who sleeps on the windowsill at the foot of the tree.

※

On the edge of the village we find this pillbox, a defensive anti-invasion guard post from WW2.

Nowadays it seems more like a bird hide, its picture window ideal for observing the local wildlife.

In the distance we spy Wittenham Clumps on the far side of the Thames.

We set off across Dyke Hills, the remains of a large defended Iron Age settlement and burial site.

Perhaps not the best route. We soon find ourselves on the wrong side of briars and barbed wire.

And it’s not the best weather. A veil of cloud has descended, the countryside is shrouded in mist. The air feels thick, visibility is much reduced, not really ideal conditions for a visionary landscape painter.

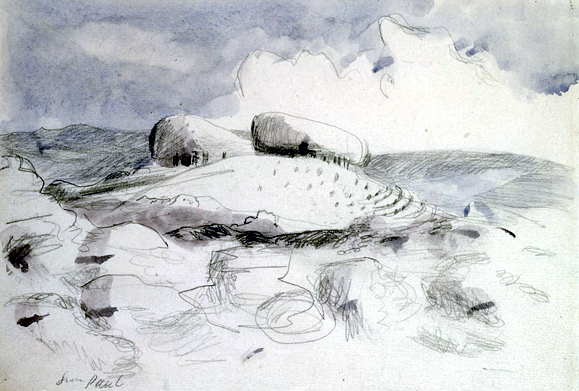

Paul Nash, Landscape Of The Wittenham Clumps, 1946, pencil & wash on paper, British Council.

Nash first visited the Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire as a child but returned to paint them throughout his lifetime. The Clumps, two conical hills crowned with trees, were ancient Iron Age hill forts. Nash was once again drawn to a landscape with folkloric, mystical or historical significance.

In 1942 Nash first visited the home of his friend Hilda Harrisson, who lived at Boar’s Hill outside Oxford.

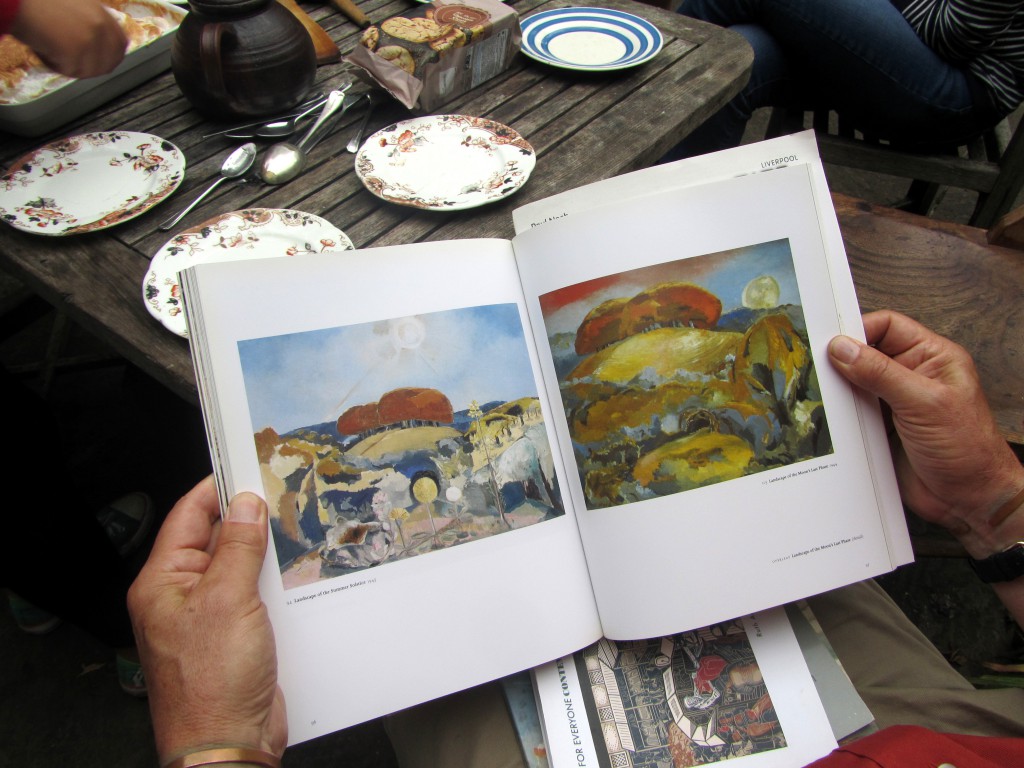

He often stayed there during periods of convalescence from illness during the war. The Wittenham Clumps were visible from the house and during his many visits Nash would sit looking across to them in the distance. This view inspired a series of works depicting the Clumps under different aspects of the moon. The moon had featured as a motif in Nash’s work since the 1920s; it symbolised the changing rhythm of the seasons, of decay and rebirth, life and death. In this magnificent series of works Nash is less concerned with a close observation of the actual scene than with an imaginative interpretation of the changing landscape. His use of colour became more rich and intense and his brushwork more fluid. In ‘Landscape of the Moon’s Last Phase’ 1944, the Clumps loom close up, and in other works they are barely visible in the distance. With declining health, Nash’s obsession with this scene reveals his tireless fascination for the ever-changing yet enduring continuity of nature.

On the Thames, a canal longboat arrives at Day’s Lock, fittingly named in homage to Paul Nash.

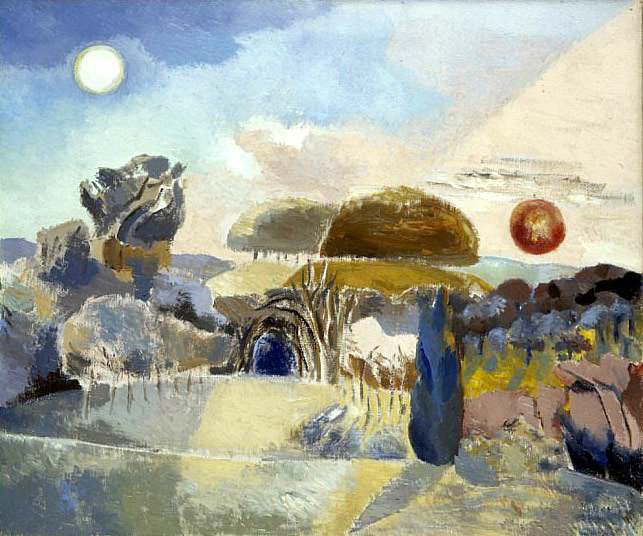

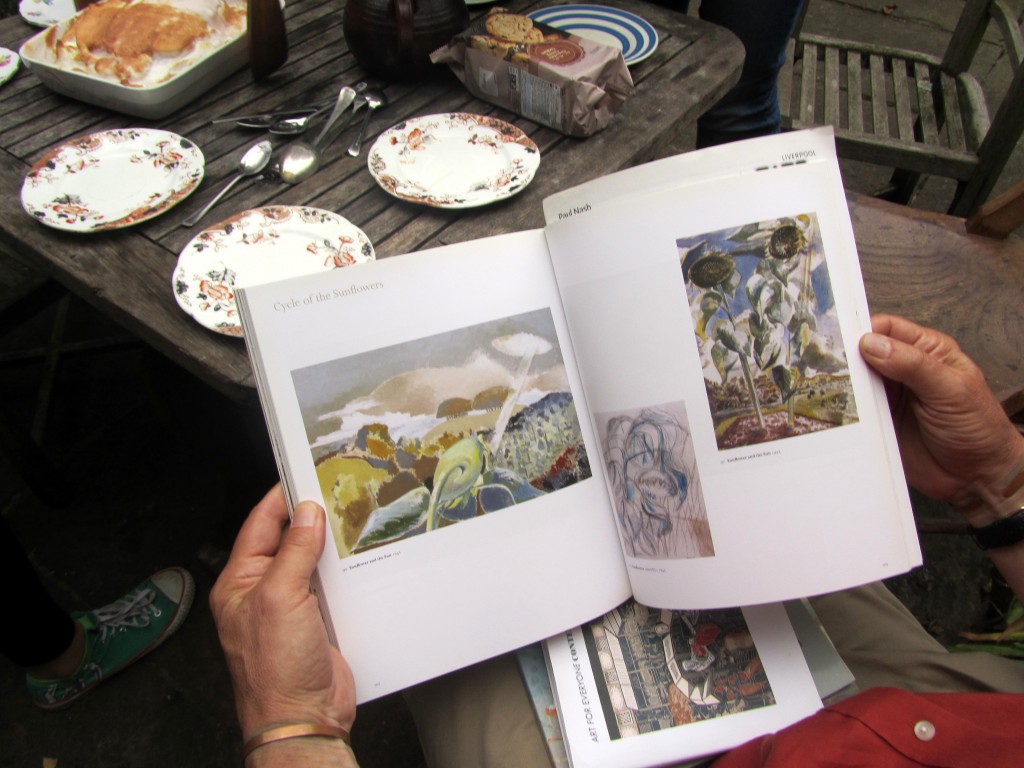

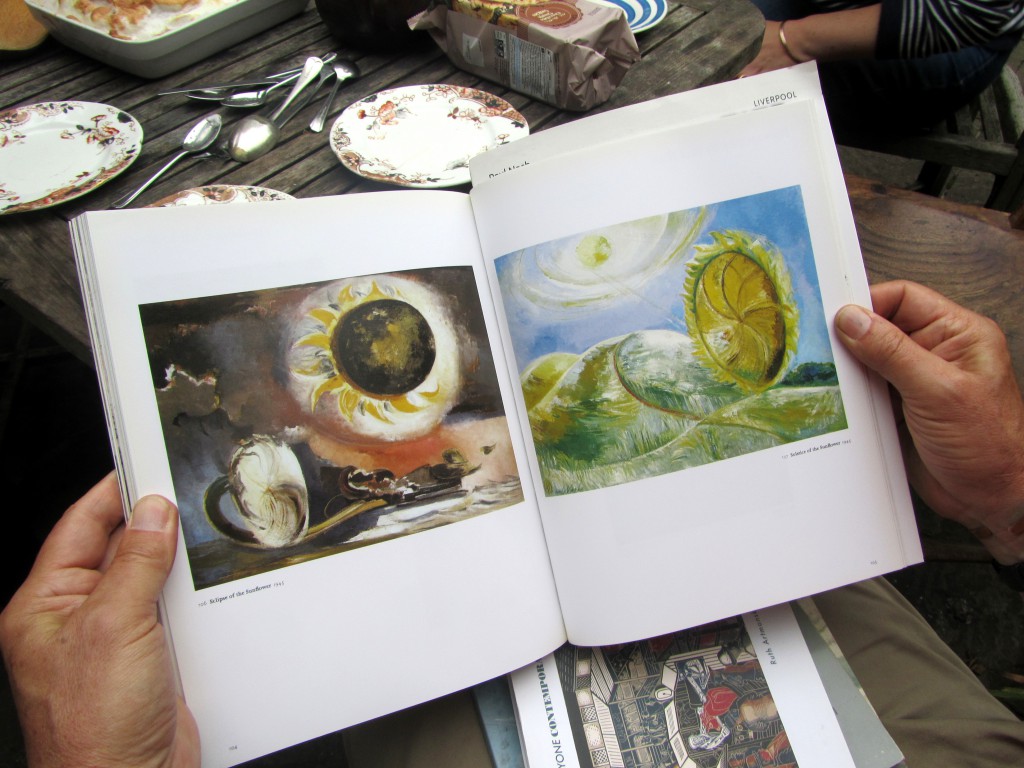

Paul Nash, Eclipse Of The Sunflower, 1945, oil on canvas, British Council.

The view of the Wittenham Clumps from Boar’s Hill was obscured during the summer by tall sunflowers in front of the window. Nash became absorbed by the rhyming shapes of the sunflower heads, the round hills of the Clumps and the moon or sun in the sky.

Nash planned to make a group of four paintings using the sunflower as an emblem of the sun in the sky.

He was unable to complete the series before he died but he wrote:

“In three pictures the flower stands in the blue sky in place of the sun. But in the ‘Solstice’ the spent sun shines forth from its zenith encouraging the sunflower in the dual character of sun and firewheel to perform its mythological purpose”.

Nash was reading James Frazer’s collection of international folklore, The Golden Bough (1926) which tells the story of an old European Midsummer festival where burning ‘firewheels’ were rolled down a hill to imitate the course of the sun in the sky. Nash found a rich source of imagery in these stories of mystical rituals associated with the land, as well as inspiration from William Blake’s well-known poem ‘Ah! Sunflower’.

Painted during the war and with Nash’s health rapidly declining, these images of the endurance of nature and the seasons are inevitably connected to his thoughts about death and the afterlife. In his essay Aerial Flowers he wrote:

“Death, I believe, is the only solution to this problem of being able to fly. Personally, I feel that if death can give us that, death will be good”.

He died in July 1946.

Paul Nash, Solstice Of The Sunflower, 1945, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Canada.

At Little Wittenham Bridge we discovered a curiously distressed sign in the hedgerow. Either it got bashed by a passing sunflower firewheel or the driver of the hedge-trimmer wasn’t paying attention.

Wittenham Clumps are within the Little Wittenham Nature Reserve which is managed by the Earth Trust, an environmental charity located at Hill Farm. I found a few words about them in The Green Road Into The Trees by Hugh Thomson –

There is a kestrel over the skyline, hovering just a fraction above the horizon so that its wings are parallel with it. And then we rise higher up the hill and it is lost against the grasses.

I’m climbing Wittenham Clumps with my old friend Robin Buxton. As we get higher, I begin to feel like a kestrel myself. The view is breathtaking. From these two hills beside the Thames, one can see back towards the Uffington White Horse in one direction and on up the Icknield Way towards the ridge line of the Chilterns the other. Directly below, the Thames winds from Wallingford around the old West Saxon centre of Dorchester, with its barrows and abbey.

No surprise that one of the twin hills that make up Wittenham Clumps should have been another Iron Age hill-fort, the latest in the line that I’ve been tracing from the west, now meeting its natural barrier at the Thames. In the eighteenth century the hilltops were wooded over, for picturesque effect: an effect that was still admired in the early twentieth century, when Paul Nash returned here frequently for a series of landscape portraits. The two prominent hills above the river are a landmark for miles, along with Didcot Power Station. From some angles in Oxfordshire, the sites seem to mimic each other; the cooling towers of Didcot are likewise grouped into two sectors. Looking down from the Clumps, the power station seems so close you could roll a pebble down the slopes and hit the concrete walls.

They had been trying to reseed the meadows below the Clumps with wildflowers for some time, without success. As anyone who’s ever tried to do the same thing on their lawn knows, ‘You can’t buy a meadow in a seedbag’, as Robin put it. Grass is much more resilient than most wildflowers, particularly if the soil is rich, so they won’t take.

The breakthrough on Robin’s meadows came with the introduction of yellow rattle in the wildflower mix, which weakened the grass to allow other wildflowers through – typically long-headed daisies, but also goat’s beard and Loddon lilies, which are like snowdrops on steroids. Now there were fifty hectares of wildflower meadow around the Clumps, and Hereford beef cattle (today there were sheep) to graze them.

Earth Trust, the nature conservancy charity established by Robin’s family, took over the Clumps in 1984. Since then, they had used no fertiliser, planted 10,000 oaks and converted an old barn as an ecology centre for the community. This was true stewardship of the land.

We came over Church Meadow around below Round Hill and climbed up through Little Wittenham Wood to Castle Hill, all the way imagining we were walking through Paul Nash paintings.

Paul Nash, Sunflower & Sun, 1942, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Paul Nash, Landscape Of The Brown Fungus, 1943, oil on canvas, National Galleries Scotland.

Paul Nash, Landscape Of The Moon’s Last Phase, 1943, oil on canvas, Walker Art Gallery.

Paul Nash, Landscape Of The Vernal Equinox, 1944, oil on canvas, National Galleries Scotland.

Before Castle Hill, looking east to Brightwell Barrow, mistakenly attributed as Wittenham Clumps.

Paul Nash, Wittenham Clumps, 1912, watercolour, ink & chalk on paper, Tullie House, Carlisle.

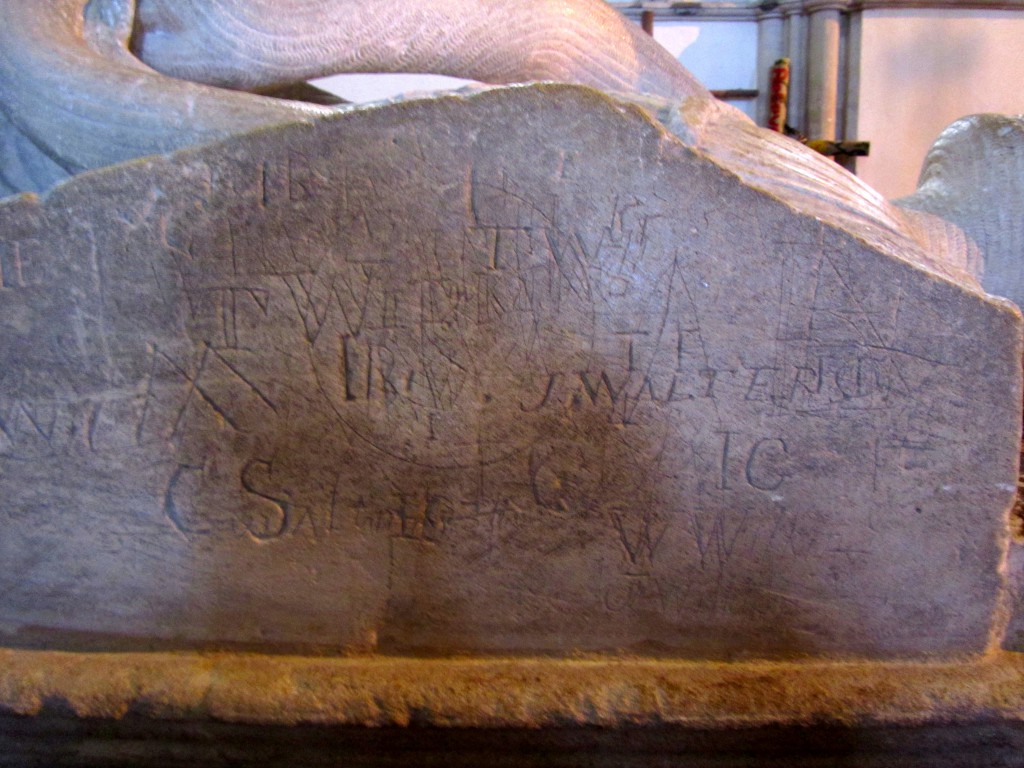

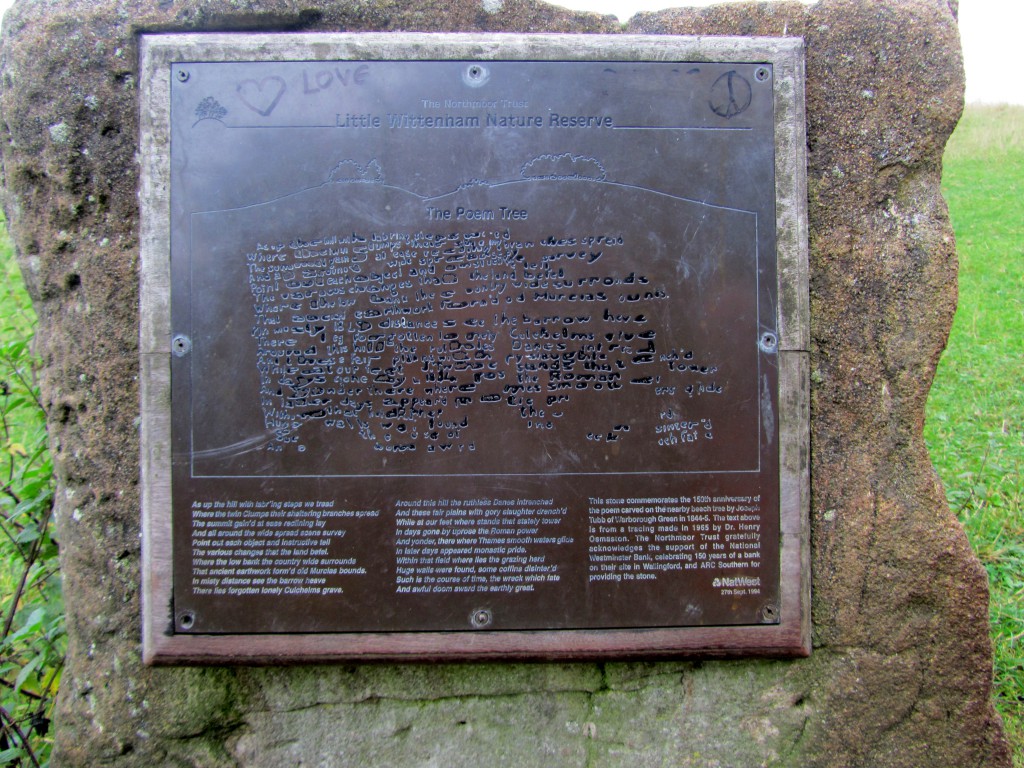

Until recently a 300 year old beech tree stood here, inscribed in the 1840s with a poem by Joseph Tubb. It became known as The Poem Tree and was still erect last time we were here five years ago.

Poet Joseph Tubb, of Warborough, carved a wonderful poem in the bark of a beech tree on Castle Hill in the years 1844-45. Tubb carved the poem over two weeks in the summer. Taking a ladder and a tent with him he carved from memory, regularly forgetting to take the original copy with him! Over the years, it became impossible to decipher all but a handful of letters of the poem, but a nearby plaque now allows visitors to feel the passion that this Victorian vandal had for the local landscape and its history.

Sadly, the Poem Tree toppled in recent years. The tree died in the 1990s but had been safely left for visitors and as a habitat for wildlife. Unfortunately once the base completely rotted, fluctuating weather conditions proved too much for the ancient trunk. The Poem Tree was found leaning precariously onto a nearby hawthorn tree, and had to be quickly winched to the ground in order to keep the area safe for visitors.

The famous Poem Tree now lies in pieces as nature intended; the deadwood will provide valuable habitat and nutrients to the surrounding area. The Poem Tree is sorely missed by the Earth Trust team and, we are sure, by all that have visited this magical piece of natural history over the years.

In the distance we can just make out the silhouette of Didcot Power Station floating through the gloom, as if its cooling towers have been working overtime, discharging clouds of steaming mist.

We step down from Castle Hill and cross over to Round Hill.

Paul Nash, Wittenham, 1935, oil on canvas, Pallant House Gallery.

Paul Nash, The Wood On The Hill, 1912, ink & wash, Ashmolean Museum.

Andrew reckoned that if Castle Hill was capped with an ancient hill fort then Round Hill was probably crowned with an ancient temple.

We descend the hill, a small herd of Herefords grazing down below, red kites circling above, wildflower plants under foot and over the crest, another hazy view of distant cooling towers.

At the bottom of the hill we come to St Peter’s church where we find a spectacular sculpture.

St. Peter’s has a number of monuments to members of the Dunche family who lived in Little Wittenham. The most notable is a large monument to Sir William Dunche (died 1611) and his wife. The monument is missing a canopy and supports, but it retains alabaster effigies of Sir William and Lady Dunche, a pair of obelisks that would have surmounted the canopy and a pair of tablets commemorating the couple’s children.

We walk back, careful this time to stay on the right side of the barbed wire fence.

Which was perhaps just as well, since the cows we’d seen earlier, through the picture window of the pillbox, were now exploring new pastures on the Dyke Hills.

※

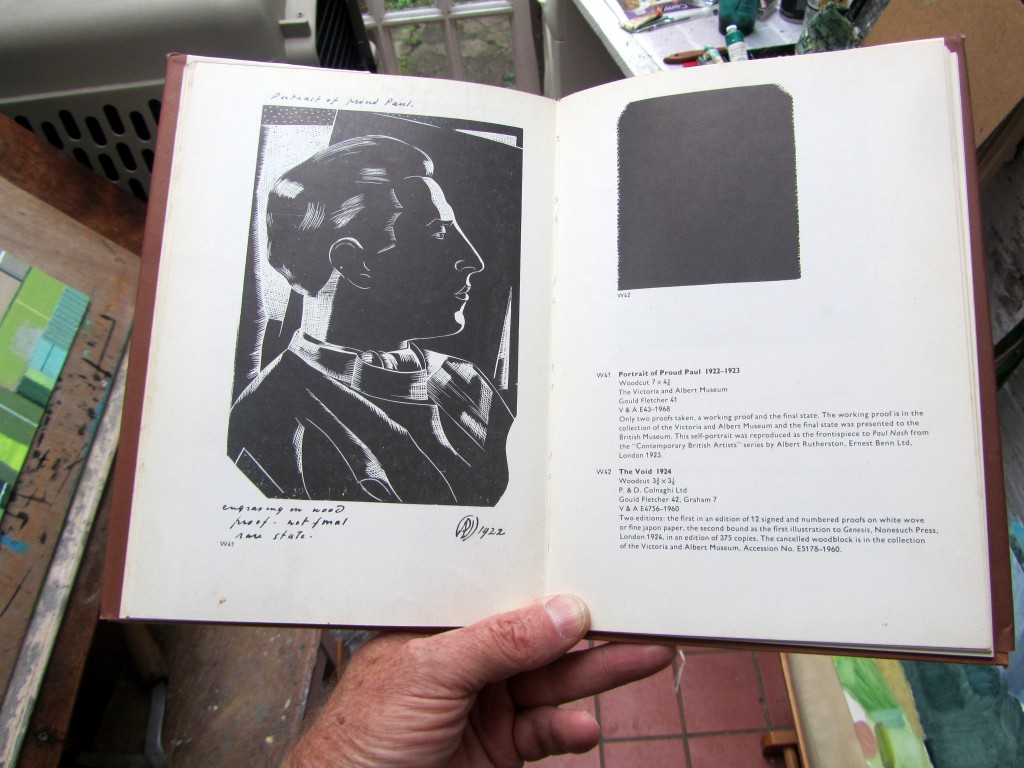

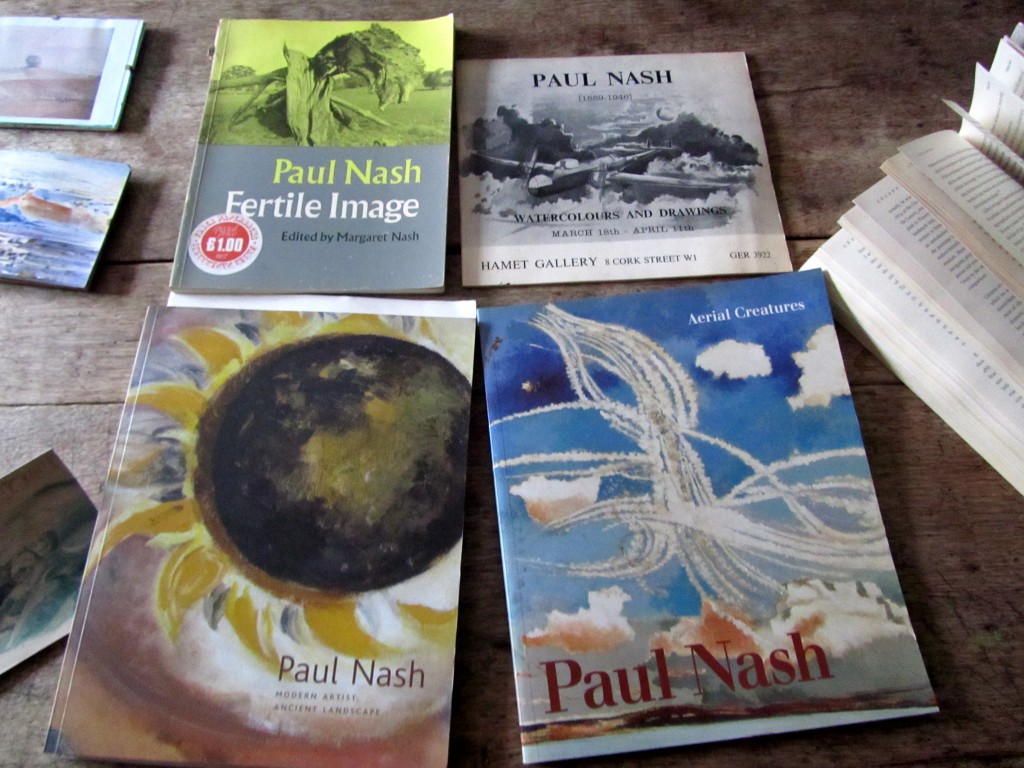

Afterwards we had tea at Jonathan’s house and pored over his collection of Paul Nash books.

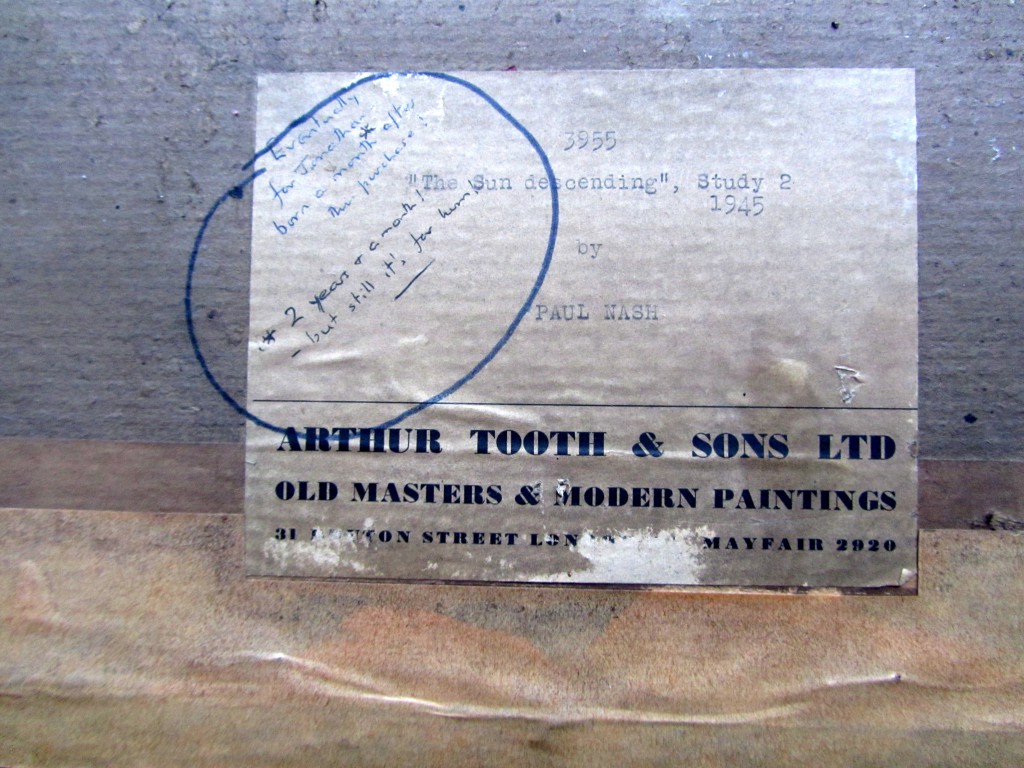

And Jonathan showed us his very own Paul Nash painting, The Sun Descending, a watercolour bought in 1946 by his father. On the back there’s an inscription – Eventually for Jonathan, born a month* after the purchase – then corrected below – *2 years & a month! – but still it’s for him!

We’d been chasing Paul Nash all afternoon and he’d been here all along. He’d been here for as long as Jonathan could remember, a constant source of wonder.

Andrew Walton / Wittenham Clumps / Paul Nash / Earth Trust / Dorchester Abbey

※

Walk the walk – Dorchester

This has reminded me of a book by Richard Long called Walking the Line…

Also Johnny Cash, he walked the line too.

A wonderful walk and something I have always wanted to do – tracing the steps of Paul Nash. I too have a Nash, a woodcut, and a collection of books on him which are some of my most treasured possessions. He has been a big influence on me too. Thanks for this.

You’re fortunate to have a woodcut. I noticed an odd one in Andrew’s book of Nash prints, titled The Void, a black hole. Minimal before Minimalism.

Wonderful. You should collect all your blogs in a book!

Thanks for the vote of confidence. Maybe you know a good publisher – blurb.

A wonderful journey through a Paul Nash landscape. Thanks for that.

Thanks for coming with us!

I agree with David. Your posts always look like something I should have to buy in a museum gift shop. Thanks for taking the time to create them.

Thanks for the kind words but I don’t want to start selling these posts. It’s payment enough to be able to read yours in return. I particularly love this one – Look y’all!

Thank you so much for this blog post. I have been away from home far too long….this a print of a tree on Blewburton Hill also a Nash site ..

Sad to see the poem tree collapsed I last saw it nearly 30 years ago with a printmaker friend who sadly no longer with us.

I wrote the poem ‘The World Turned Backwards’ in the 1990s and it is available to read in the Salt Pamphlet ‘Last Farmer’ 2010 here:

https://www.scribd.com/document/281575946/Shaun-Belcher-Last-Farmer

World Turned Backwards

Charged by a singular emotion

amongst the complications of this country

we shoot eastwards into more night,

leaving light as a fading red tinge

on beeches cresting twin hills.

Moths flash into the windscreen,

spilt straw swirls on the verge

as we slide up inclines

and brake smoothly into yellowed suburbs.

Then between towns a high dark hill

and beyond a sudden swathe of light.

Under floodlights

harvesters turn night back to day.

A combine, all whirr and spin

thrashes the crop to grain and grit.

The memory of it haunts me still

though I forget journey, place, time,

all lost in that clash of gears

as the machine hurtled forward

toward profit and gain.

Alone in the company of others

I shoot eastwards toward you.

Airports, ski-slopes, red-brick motels.

A blue steel sign for Maidenhead, M5, M4.

Roads fence these new fields in.

Pasture turned to all-night golf ranges,

Seven-Elevens, Granadas and Little Chefs.

Behind us in a more perfect night

the storm has traced plans of invisible cities

across the wheat-fields of Dorset and Wiltshire.

Here we sit, idling, staring at the spectacle

of revamp, infill and empty spec. building.

I want to turn the world backwards.

Push it back through seasons 150 years

so that I can stand and watch

Joseph Tubb of Warborough

chiselling his love poem in that green beech bark.

Now all his letters have grown bloated,

swollen like the new towns and London suburbs.

Then each was crisp and clear cut,

sharp as a an oil lamp glinting across a field.

His tree,

writing itself against barley, snow and stars

died eventually, killed by that ring of words.

Instead of all these overgrown paths to you

I dream now of a field new mown and at the border

a broken down fence of words.