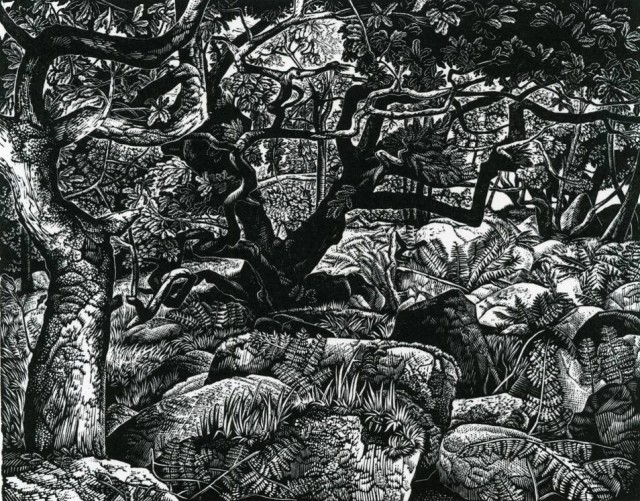

When Howard Phipps first showed me this engraving it seemed to refer to a type of oak wood more familiar from France or Spain. I was so intrigued by it that I asked if he might write something for us, and here is his reply:

As an artist frequently involved with landscape I have always had an interest in trees, in particular the Beech; perhaps this is because I spent my formative years in Gloucestershire where the Beech is a noticeable and fine feature of the Cotswolds. Later on I lived in Devon for four years, where the Oak is a more common sight. A fellow artist native to that county took me up onto Dartmoor to visit a very small oak woodland, which I discovered was something of an ecological marvel. This was Wistman’s Wood, situated some 1400 feet above sea level but surviving in a windswept landscape – a small fragment of primeval forest. I was fascinated by this subject for unlike the mature oaks of the lower slopes, these trees are low, perhaps only twenty feet in height, but with limbs that spread out to an unusual extent, contorting as they do into extraordinary shapes. My first response was to make a large pencil drawing from the edge of the trees, in August on days when there was little sun. This meant that the light penetrated evenly and I was able to observe the dark limbs of the central oak against the complexity of its surroundings. The ancient oaks are themselves covered in ferns, lichens and mosses, but so too are the granite boulders from between which they grow.

Wood engraving is sometimes described as drawing with white lines, since I begin with a blackened boxwood block; the complexity of textures in Wistman’s Wood seemed to lend itself to this medium, and this is one of the largest endgrain blocks that I have engraved.

In Flora Brittanica, Richard Mabey writes in the section devoted to the Beech family, Fagaceae, (which includes oak, birch, alder, lime, poplar, willow, maple and ash) “In Wistman’s Wood on Dartmoor, the oaks are elfinesque. John Fowles has written an incomparable portrait of them in the closing chapter of The Tree:

The normal full-grown height of the common oak is 30 to 40 metres. Here the very largest, and even though they are centuries old, rarely top five metres. They are just coming into leaf, long after their lowland kin, in every shade from yellow-green to bronze. Their dark branches grow to an extraordinary extent laterally; they are endlessly angled, twisted, raked, interlocked, and reach quite as much downward as upward. These trees are inconceivably different from the normal habit of their species, far more like specimens from a natural bonsai nursery. They seem, even though the day is windless, to be writhing, convulsed, each its own Laocoon, caught and frozen in some fantastically private struggle for existence.”

John Fowles’s The Tree is now recently republished. See more here.

Absolutely love this picture. Had a go at woodcut recently…..best left to the real practioners!

This fabulous woodcut truly encapsulates Wistman’s Wood. I love it! I was struck by the synchronicity of this, as I wrote my Times column (Nature Notebook) about it on the same day – Sat Feb 7th. That day it had snowed, and there was a Snow Buddha at the entrance to this magical and precious place.. Some good references to Fowles and Mabey, as well. Lovely writing.

Thank you!

Thanks Miriam. I wish I’d seen your piece in The Times. Wistman’s Wood must’ve looked especially wonderful covered in snow.