Pagliaghju was difficult to find. We drove past it a few times without even seeing the sign. Each time we looked it up the spelling was different. The sign was invisible and the spelling was variable. I’ve seen Pagliaghju, Palaggiu, Pagliaju, Palaghju, Pallagiu and finally Palagahiu.

There was a small turning off the main road between Sartène and Tizzano, but it was easy to miss. We’d already overlooked it a couple of times a few days earlier when we came to visit Cauria, but this time we were more determined. Eventually we spotted the name Palagahiu chalked on an adjacent wall next to an entrance blocked with boulders. This was not an invitation to drive down the lane.

We set off on foot along a dry dusty track through the maquis in the full glare of the midday sun

until we found this great welcoming holm oak

which turned out to be not one but a circle of six dancing together in a companionable shade.

The way in was marked with an arrow.

We had arrived in the zone of stones.

The first Corsicans may well have hopped over from Sardinia, which was settled half a million years ago, or they may have come by way of Tuscany… A great change came in around 3000BC, with an invasion, or perhaps an early form of cultural or religious evangelism. All we know is that the urge and skill to erect megalithic buildings filtered down from Provence to Corsica, through Sardinia, en route to North Africa. A preoccupation with death, or life after death, was already present, as new, elaborate burial techniques were adopted to honour the dead. What Corsicans really excelled at were menhirs; over 500 have been found on the island, a density no other place in the Mediterranean can equal.

The island went through several distinct megalithic phases. At first, bodies were interred in underground cists or stone chest tombs, which were marked by circles of simple menhirs, as at Settiva. In the second stage, c.2500BC, the dead were buried under classic, above-ground table-style dolmens, and menhirs were aligned around them. These are smoother and more refined stones, with the outline of a head; sometimes they look more phallic than anthropomorphic. The 258 stones at Pagliaghju near Sartène form the most important alignment in the Mediterranean.

Dating from 1800BC, these are seven groups of 258 stones – six are over 10ft/3m high, lined up on a north-south axis, some still upright, others tilting at various angles, some flat on the ground. Some are carved, mostly rudimentarily, into what Roger Grosjean, who studied them in the 1960s, labelled ‘menhirs protoanthropomorphes’, although there are also three proper statue-steles engraved with swords. Grosjean saw them as a magical army, lined up to thwart invaders by sea, and at twilight they take on the rosy glow of the setting sun.

Corsica: Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls

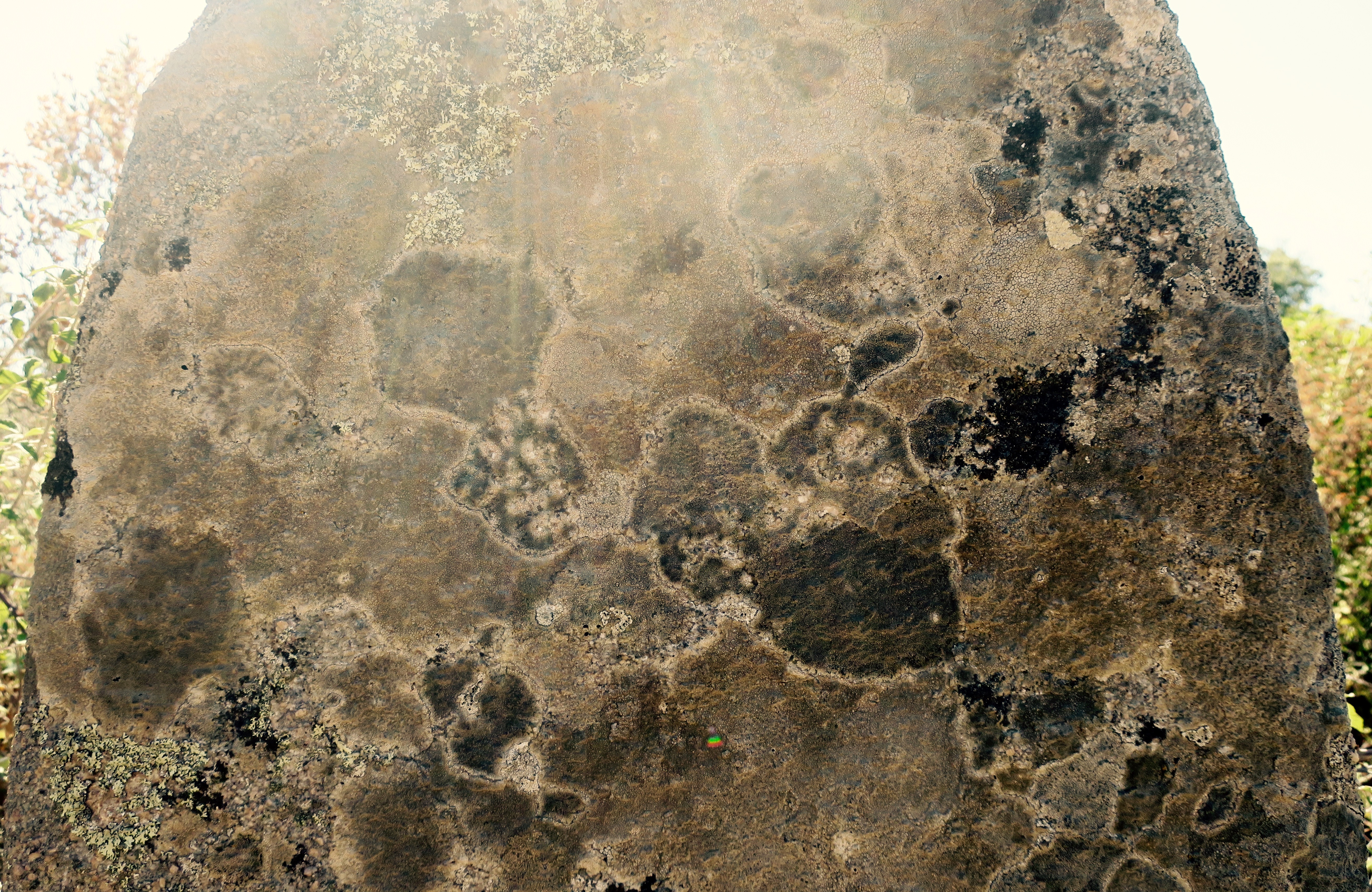

The standing stone’s lichen is like an aerial view of the trees.

A map of Europe with Cornwall attached to the Scillies and Sicily swollen like a bunion.

It looked like Chris Kenny had already been here.

Known locally as Le Cimetière des Turcs (The Turkish Cemetery), Palaggiu had, it is said, 258 menhirs once standing hereabouts in three great straggling lines over 100 metres long, with a further double avenue waving like a short broken arm at ninety degrees to the rest of the monument. But not anymore, though. For nowadays even the most optimistic of visitors would be hard pressed to tally up more than 125 menhirs standing, leaning and prostrate amidst the granite chaos here on the sandy uplands north-west of the Navara Valley. Indeed, my two long visits of 26th and 28th November 2003CE were spent sifting through the scores of fallen stones like ‘megalithic asparagus [with] their tips crushed into each other, their roots still in the ground’, as I wrote in my field notebook.

Among the confusion, four impressive main sweeps of stones still remain upright, and it is these groups of menhirs that define the Palaggiu lines and help to make this monument such an essential visit. The most impressive of these groups is a line of ten menhirs – three reduced to virtual stumps – which stand on the northern side of the alignment. The seven that remain intact stand to impressive ‘human-sized’ heights. Of the scores of menhirs on this line of the monument, only one other stands truly upright, though this nine-footer is the largest of all those at Palaggiu. Diagonally opposite this venerable survivor, eight large menhirs stand together in near contiguous fashion along the otherwise almost totally denuded southern alignment. Unlike the chaos opposite, neither fallen stones nor even stumps protrude from the sandy soil. However, at the far south-westerly end of this alignment, nine uprights – all of them considerably smaller and, again, virtually contiguous – crowd together, stranded and utterly adrift from the rest of the other stone rows. Similarly, at the other end of this bare alignment stand three large handsome menhirs, and squatting amongst them one hunched dwarfish curiosity. Of the double avenue that formerly stood at ninety degrees to these main alignments, all the stones now lie wretchedly prone, as though some pitiless giant had taken his size 500 Doctor Martens and systematically ground them all into the dust. How many stones were there here? It is difficult to guess, for they are mostly mangled beyond comprehension.

There are, however, secrets still to be yielded here at Palaggiu. For the general axis of the monument directs our eyes inexorably to the huge knobbly mountain of Punta d’Alpuzzo on the near south-westerly horizon, contemplating a possible ancient interest in the winter solstice sunset. But the singular nature of other Corsican prehistory suggests that a very different and specific veneration may have been behind the erection of this once massive field monument.

The Megalithic European: Julian Cope

We lingered awhile among these venerable ancestors, raised long ago to stand the test of time, to bear witness to the passing seasons, gradually sinking back down to earth, swallowed up into the evergreen maquis, the aromatic and everlasting monumental shrubbery – quick now, here, now, always…

That will be the Corsican saint Florent.