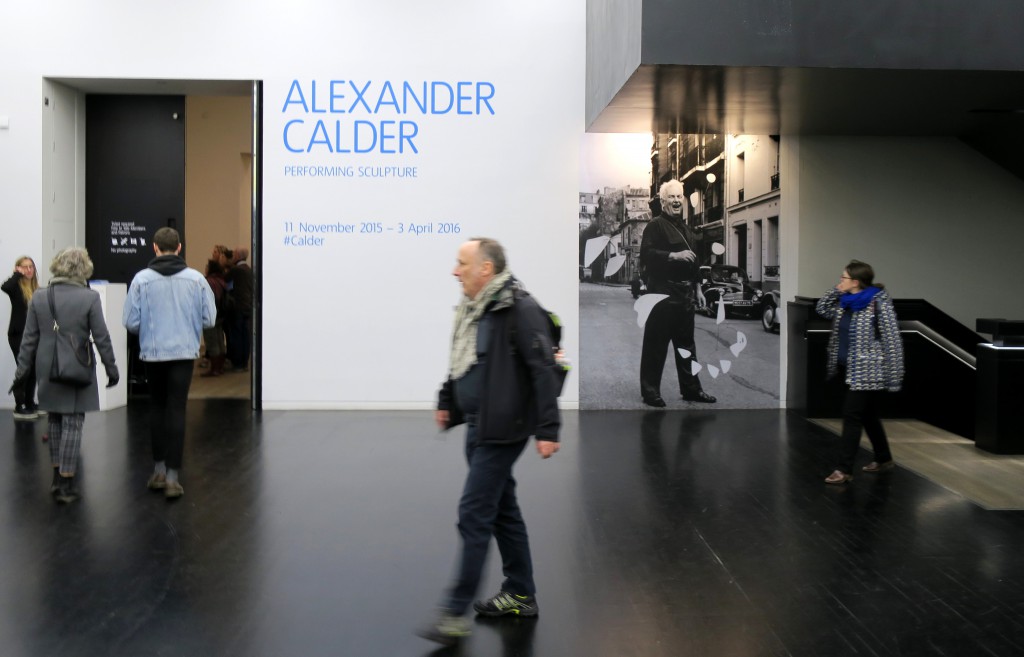

This was another camera-shy exhibition. We had to switch off our cameras at the entrance, even though it was full of exhibitionist ‘performing sculptures’, all of them posing and pouting and teasing. Mostly they’re mobiles though none of them moved, their motion implied through poise and balance. Yet despite these contradictions, it’s a fantastic show, elegant and vibrant and fun.

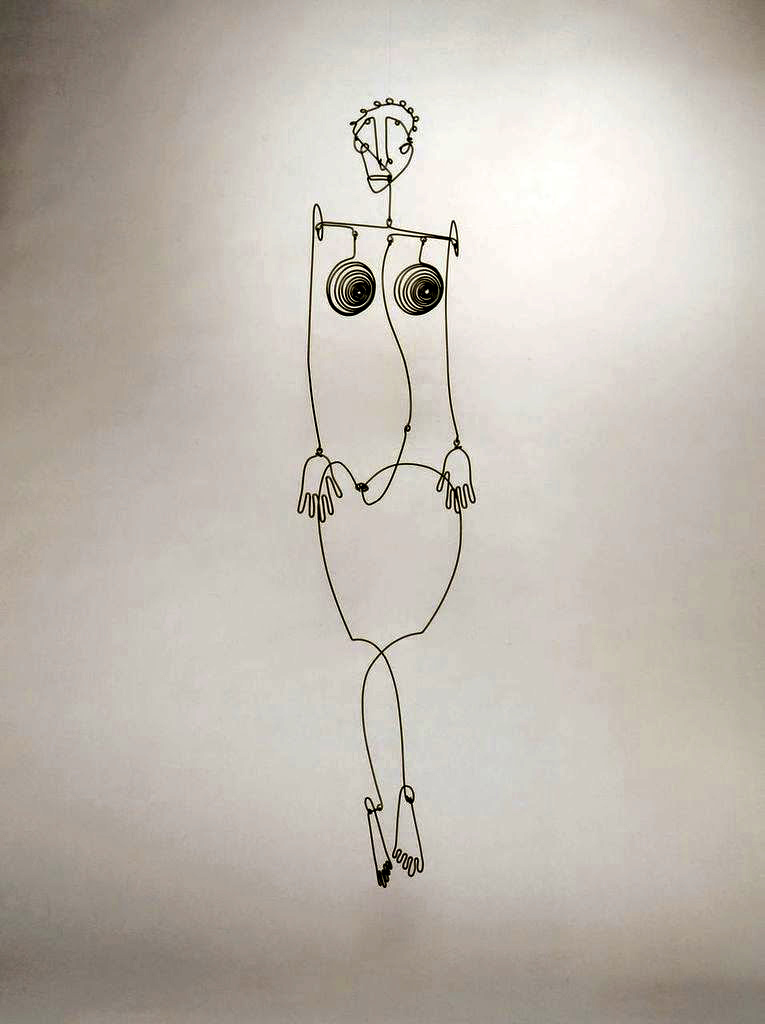

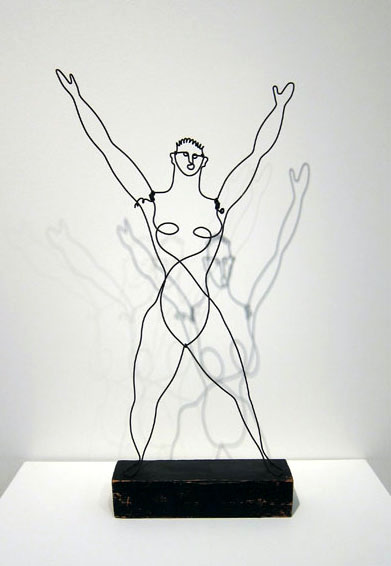

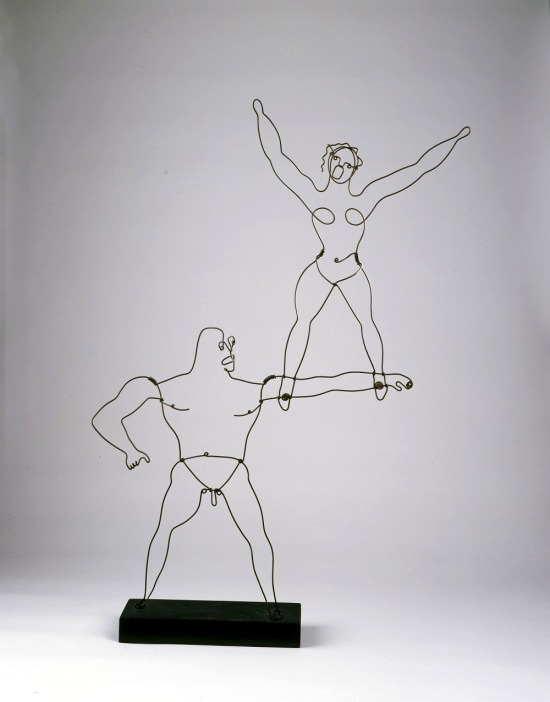

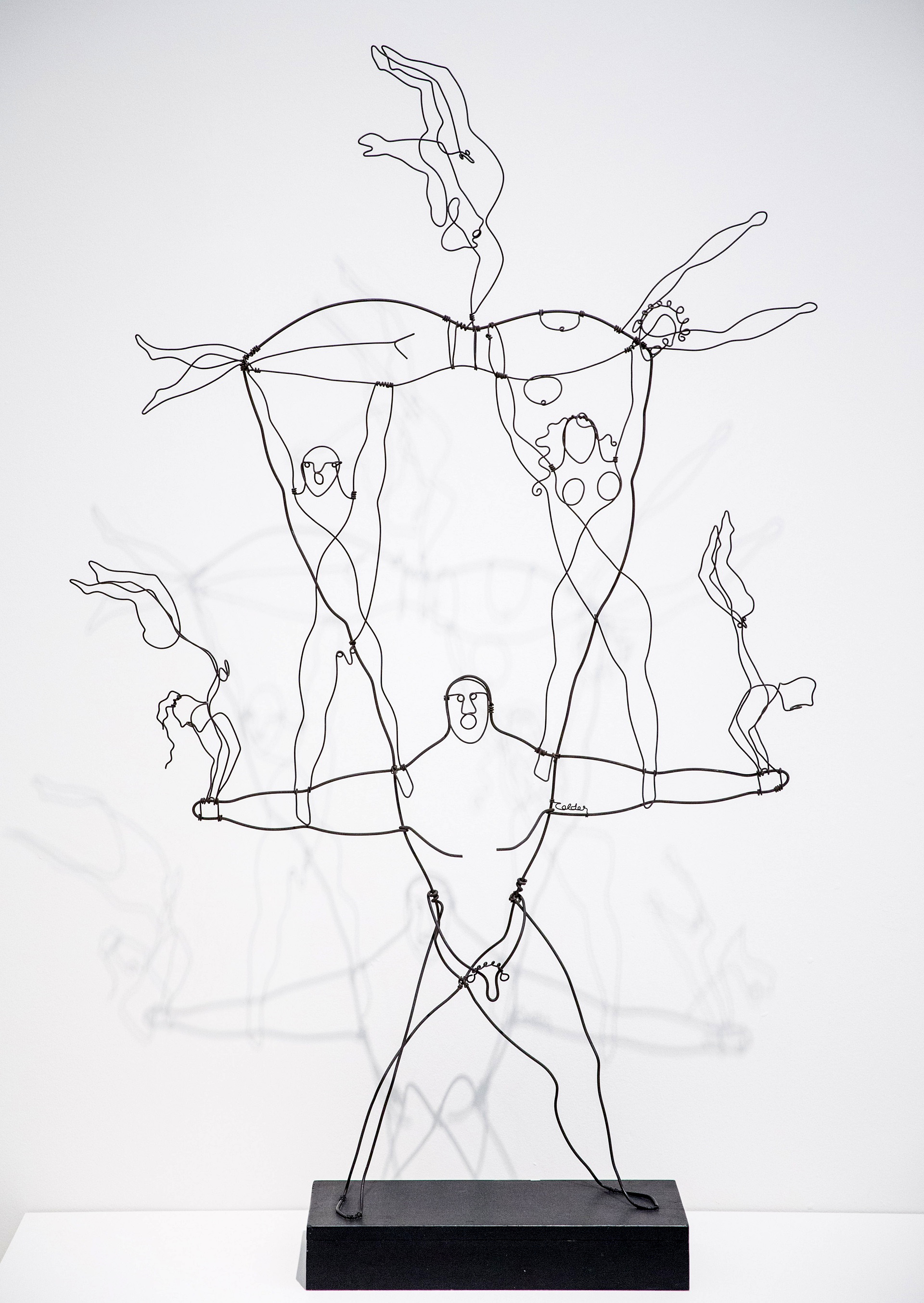

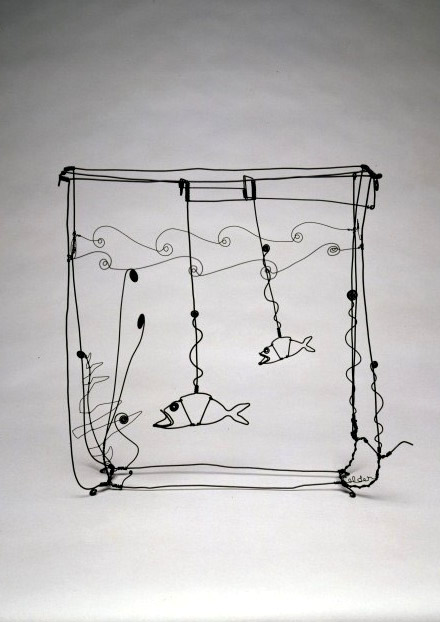

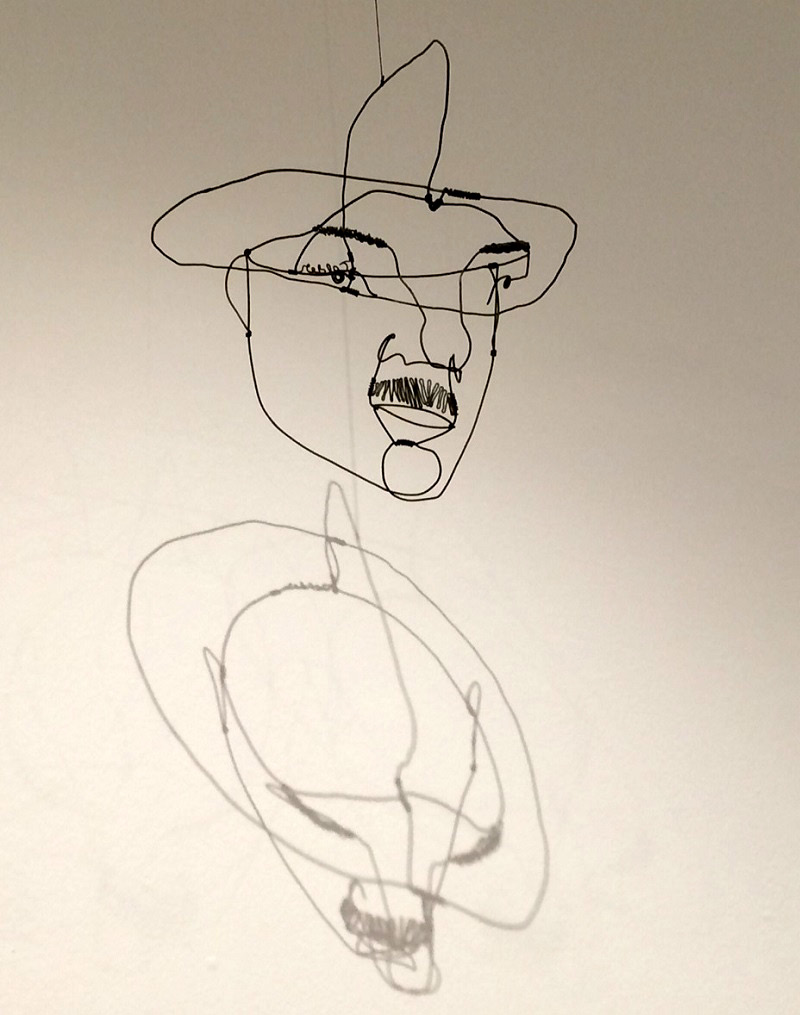

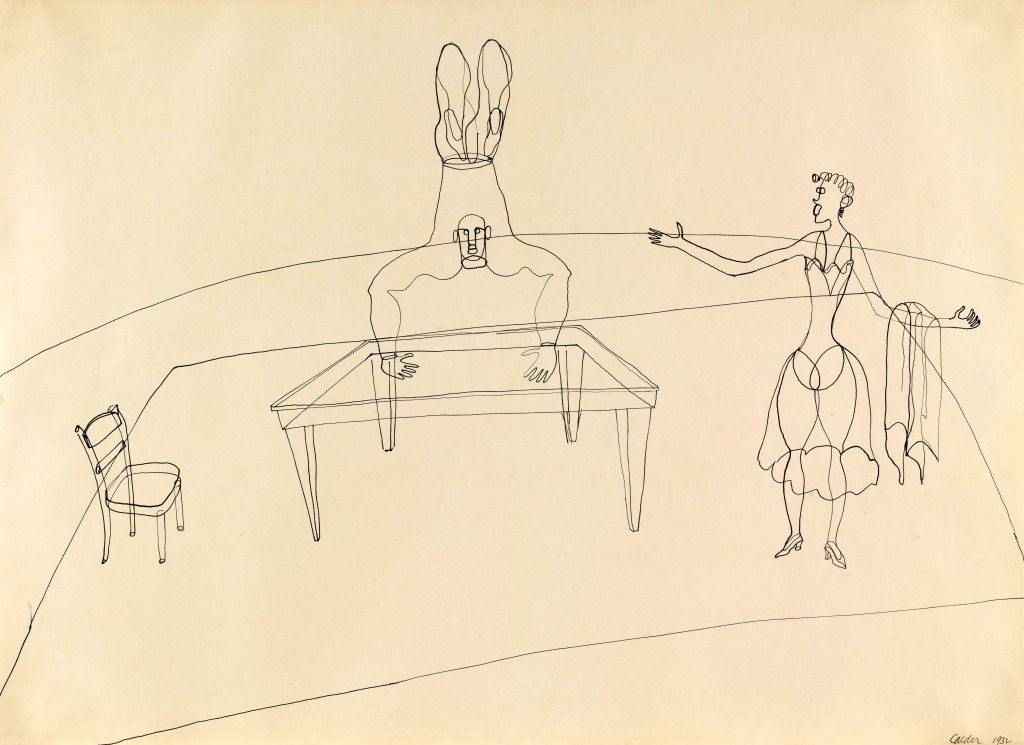

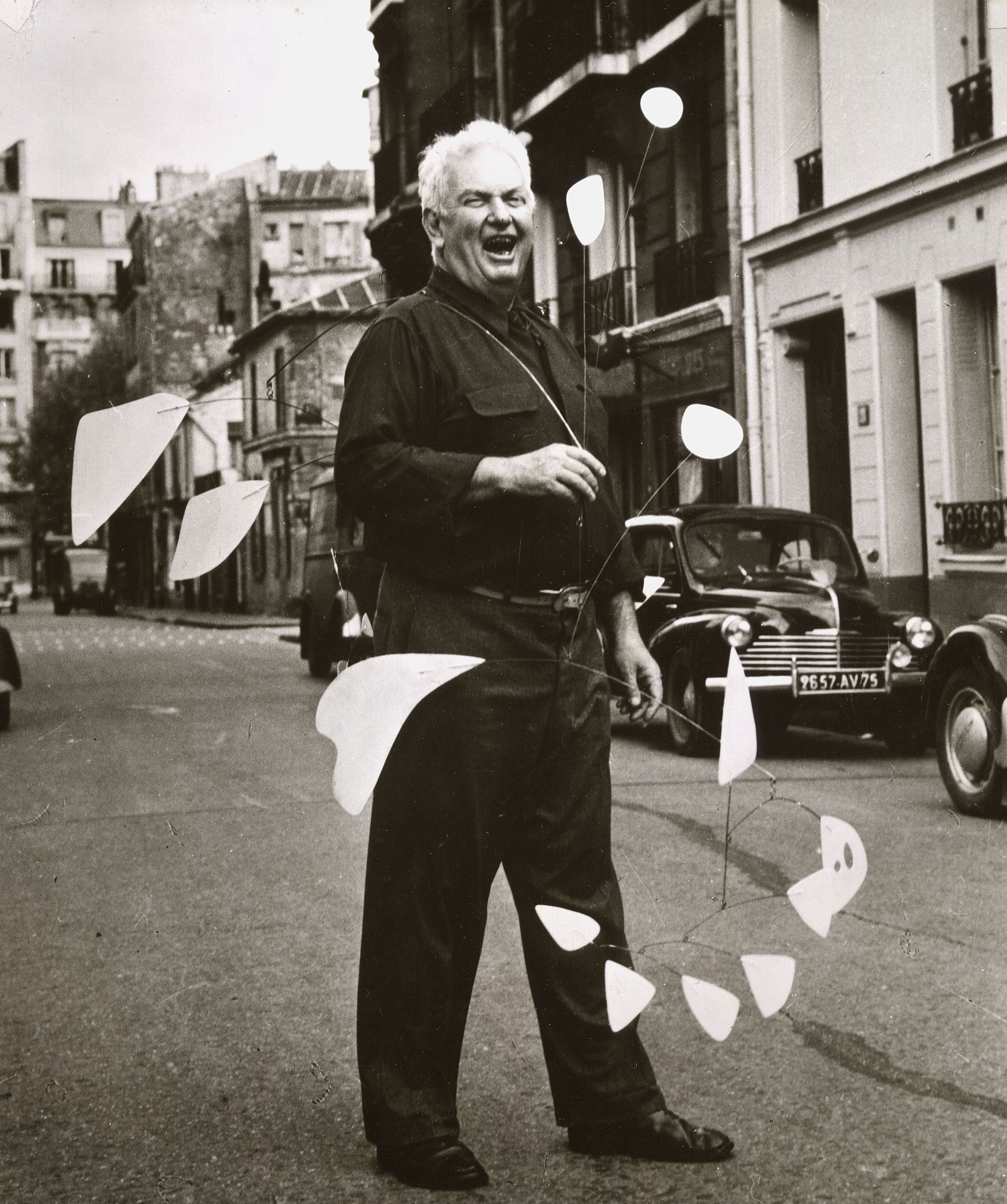

Widely celebrated as the originator of the ‘mobile’, Alexander Calder (1898-1976) was one of the most innovative and influential American artists of the 20th century. This exhibition focuses on Calder’s pioneering approach to sculpture, as he overturned many traditional assumptions about the medium. His early works in wire defined figures with delicate lines in space rather than a solid mass. Many of his works hung from the ceiling rather than standing on a plinth.

Calder’s father and grandfather were both noted sculptors, and his mother was a painter. As a child, Calder also showed some talent as an artist. However, he earned a degree in mechanical engineering in 1919, and spent several years in different jobs before studying painting at the Art Students League in New York in 1923. He then worked as an illustrator, continued to paint, and began to sculpt in sheet metal and wire before setting off to Paris in 1926.

At a time when sculptures were still usually made from stone, bronze or wood, Calder’s use of wire was seen as radically new.

Calder first established his reputation through the performances that he staged with ‘Cirque Calder’, a complex, unique body of work which attracted a devoted following among the Paris avant-garde.

He had a lifelong interest in the performing arts. Over the years his friends and collaborators included modernist composers such as Edgard Varèse, Virgil Thomson and John Cage, as well as leading figures in contemporary dance such as Martha Graham and Ruth Page. His explorations of sound and movement, of chance and intervention, and the ways in which an artwork can respond to or alter its surroundings, took place within a milieu informed by developments in music and choreography as much as by fine art. Embodying the vitality of dancers or acrobats, Calder’s sculptures were performers in their own right.

(Goldfish: Henri Matisse)

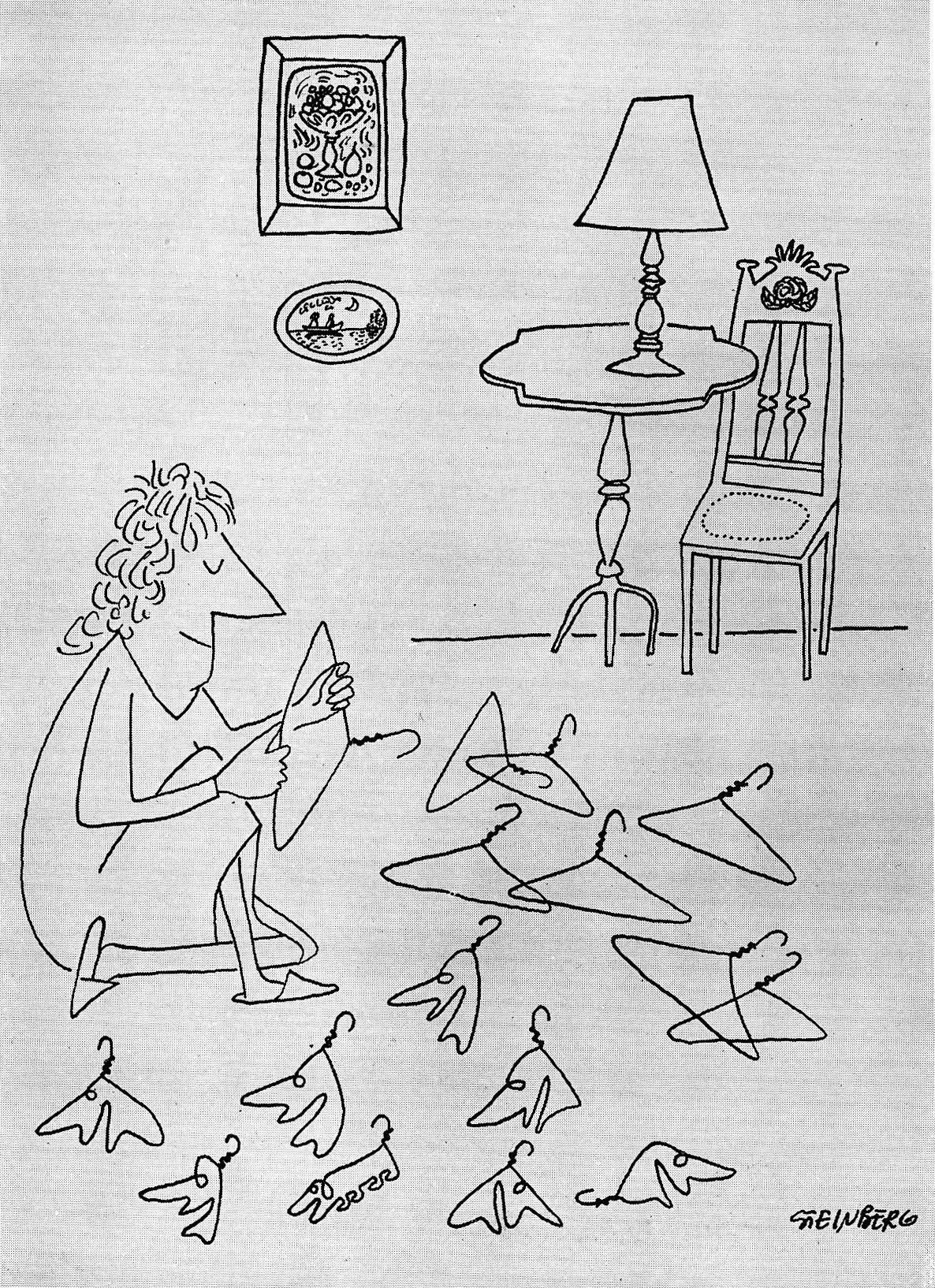

(Untitled: Saul Steinberg)

(Our Friends In The Circus: Quentin Blake)

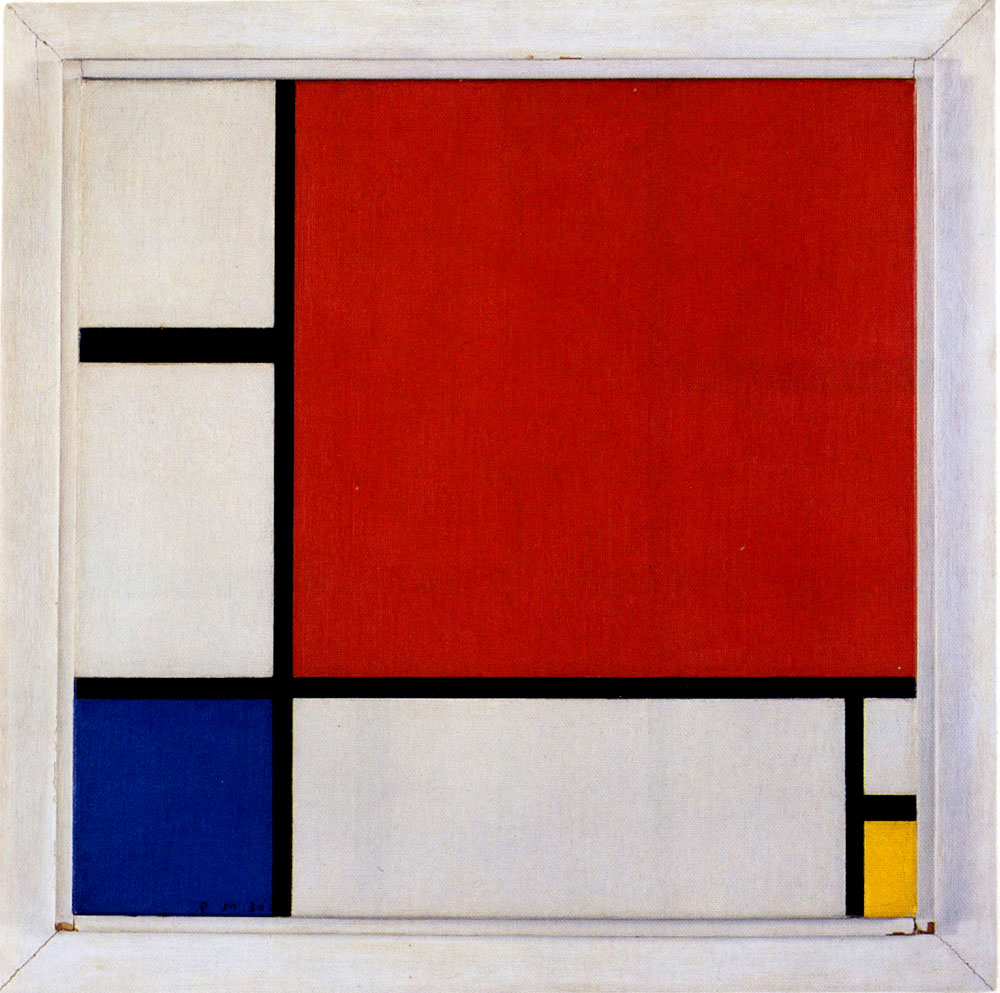

(Composition In Red, Blue And Yellow: Piet Mondrian)

In 1930 Calder visited the studio of painter Piet Mondrian, one of the pioneers of geometric abstraction. Seeing the coloured cardboard rectangles that Mondrian attached to the wall as compositional aids, Calder suggested that it would be interesting to make these geometrical elements move about. Mondrian disagreed.

This first serious encounter with abstraction was a revelation. Calder described the studio as ‘the shock that converted me. It was like the baby being slapped to make its lungs start working.’

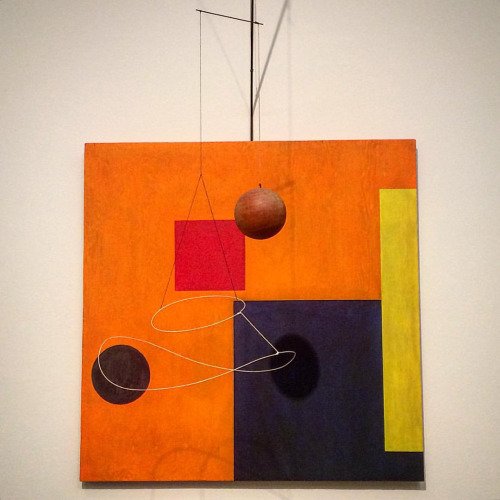

Calder was always interested in the interaction between his hanging works and their surroundings. In the group of works made in the late 1930s, the relationship between foreground and background is not only emphasised, but becomes part of the work. In each one a painted wooden panel provides a backdrop in front of which coloured shapes are suspended, suggesting two-dimensional abstract paintings that have taken kinetic three-dimensional form. Many of these works have not been on public view for decades, and have never been exhibited together before.

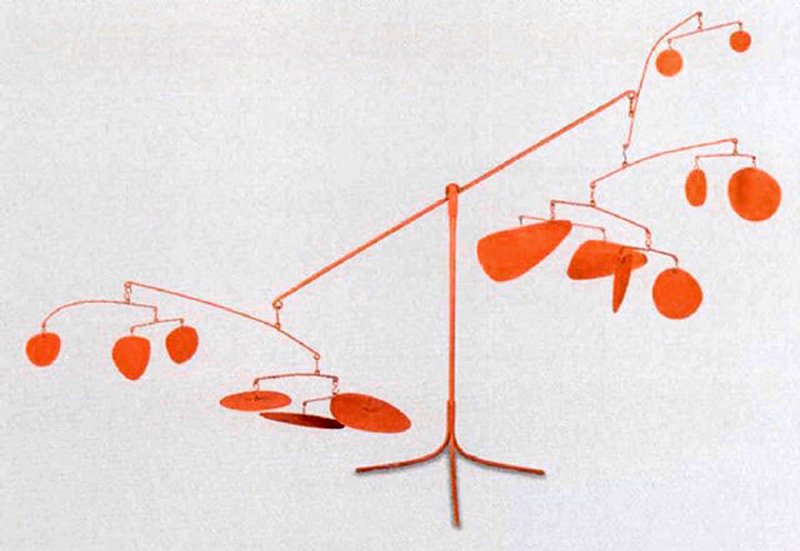

Most of the works in this exhibition date from the 1930s and early 1940s, during which he tirelessly explored different approaches to making mobiles – a term coined by Marcel Duchamp in 1931 to describe Calder’s kinetic abstractions.

Chef d’Orchestre

Performing Sculpture – Earle Brown’s Calder Piece

Earle Brown was a major force in contemporary music and the American avant-garde since the 1950s and the creator of open form, a style of musical construction greatly indebted to the works of Alexander Calder.

In 1963, Brown and Calder embarked on a musical collaboration, for which Calder made Chef d’orchestre, where four percussionists are ‘conducted’ by the mobile. Some 100 percussion instruments are employed in a performance where the movement of the sculpture is read by the percussionists, responding to the varying configuration of its elements.

As well as functioning as conductor, the musicians actually play the mobile, making each performance both visually and musically unique. It was not until 1966 that the work was finished and Calder Piece was first performed at the Théâtre de l’Atelier in Paris, early in 1967.

Calder Piece is one of a kind and Earle Brown insisted that the music must never be independent of Chef d’orchestre. This major revival of a work not played for over 30 years is its UK premiere, performed by the percussion ensemble of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in collaboration with Gramophone Award-winning conductor Richard Bernas.

This is the latest in a series of great shows at Tate Modern in recent years. There have been memorable exhibitions of work by Joan Miró, Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Sonia Delaunay, Agnes Martin and now Alexander Calder, all wonderful and all frustratingly unphotographable.

※

Outside I consoled myself with pictures of the Bankside bubble man. He didn’t seem to mind being photographed and his bubbles actually moved. They were performing sculpture too.

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture