Sitting here on lockdown, having earlier walked our prescribed exercise route, carefully plotted through burgeoning local parks and side roads, the trees and hedges heavy with blossom and alive with birdsong, more so it seems than ever this year. Strange contrast with the quiet tragedy unfolding around us, the closed doors and closed curtains and the quiet ambulances in the streets. I’m itchy to be away from here but there’s nowhere to go. So I’m looking back through old photos and I find myself in Sicily, two years ago when we were free to go wherever we pleased. We were staying in Syracuse, on the island of Ortigia, and each day we went off in a different direction. On this day we headed inland, due west to the ancient prehistoric site of Pantalica.

We came via spectacular landscapes along twisting roads through steep wooded valleys and approached along a peninsula plateau above two steep river valleys. The Anapo is down to the left and the Cava Grande is below the trees on the right. We pulled off the road and explored the paths on foot.

We were in the middle of a great plateau, peering into a deep canyon.

But Sue wasn’t looking over the edge, she was staring down at her feet.

At first glance I don’t see anything, except maybe a couple of tiny fallen seeds, but then they become two legs and above them I see antennae and gradually the outline of a cunningly disguised insect.

A strange mottled creature made of gossamer, lichen and straw.

A stone cricket or dried grasshopper

And then it was gone.

This is a porous and absorbent landscape, welcoming and so ready to swallow you up. It’s easy to feel a part of it. In the same way that you might want to stretch out your arms and embrace the whole vista to the horizon, so this land would like to reciprocate and do the same to you.

Grotta San Micidiario

The plateau above the Anapo valley to the south is beautiful open countryside, with characteristic old farmhouses and low dry-stone walls. Dark carob trees provide welcome shade and the olive groves are renowned for the high quality of their oil (in 2015 the production of three farms was voted best in the world). Shepherds pasture their flocks and small herds of cattle wander around apparently untended; the sound of their neck-bells lingers after their passage. Byzantine tombs and caves in the area show evidence of Neolithic and Bronze Age occupation.

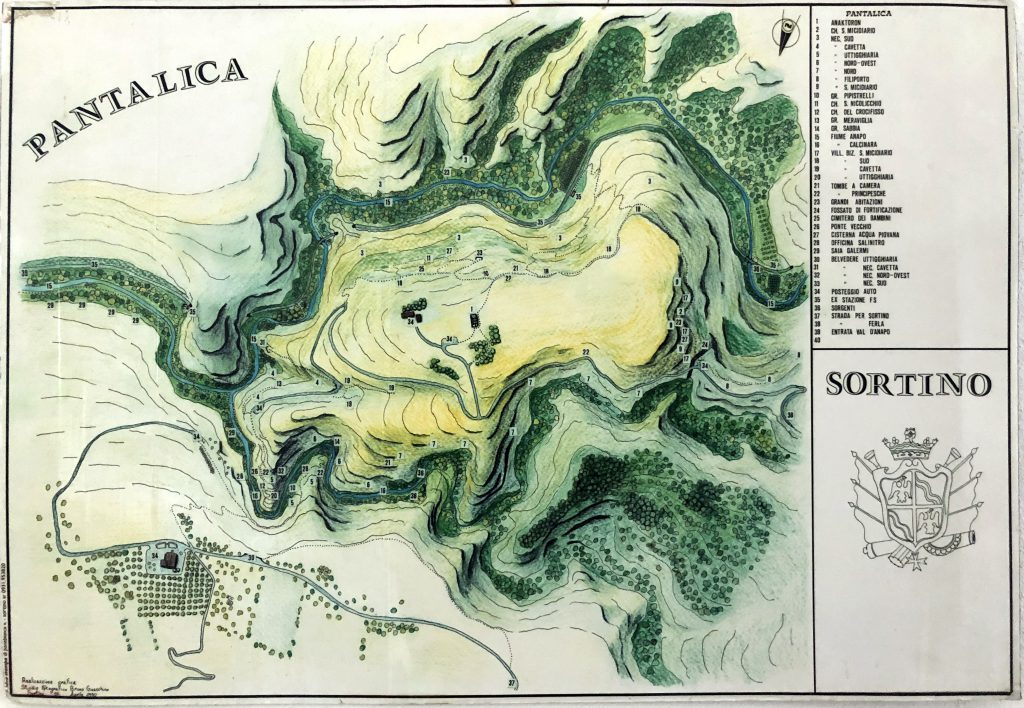

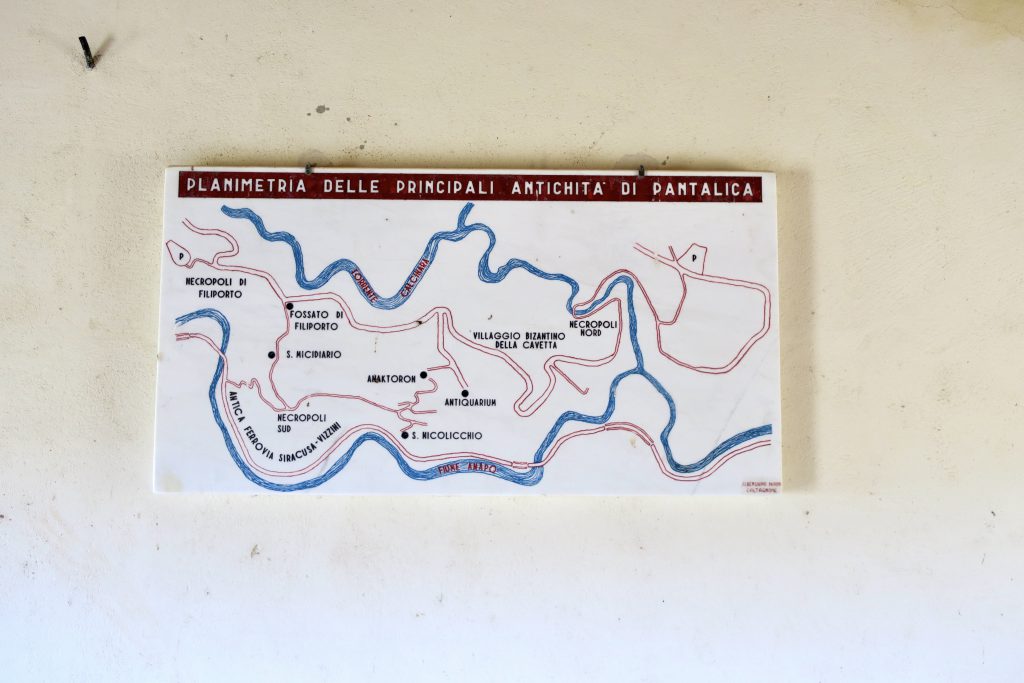

Near the picturesque village of Cassaro… is the Valle dell’Anapo, a beautiful deep limestone gorge run by the Azienda Forestale. A map of the paths is available at the entrance. No private cars (or any pet animals) are allowed: a van takes visitors for 8km along a rough road on the course of the disused narrow-gauge railway (and its tunnels) which runs along the valley floor, once the Syracuse-Vizzini line. The vegetation here includes ilexes, pines, figs, olives, citrus trees and poplars; wildlife includes birds of prey such as the peregrine falcon and Bonelli’s eagle, also the porcupine and the pine marten. The only buildings to be seen are those once used by the railway company. Horses are bred here and picnic places are provided with tables. In the centre of the valley there is a good view of the tombs of Pantalica high up at the top of the rockface. There is another entrance to the valley from the Sortino road, where maps are also available.

Ellen Grady: Blue Guide Sicily

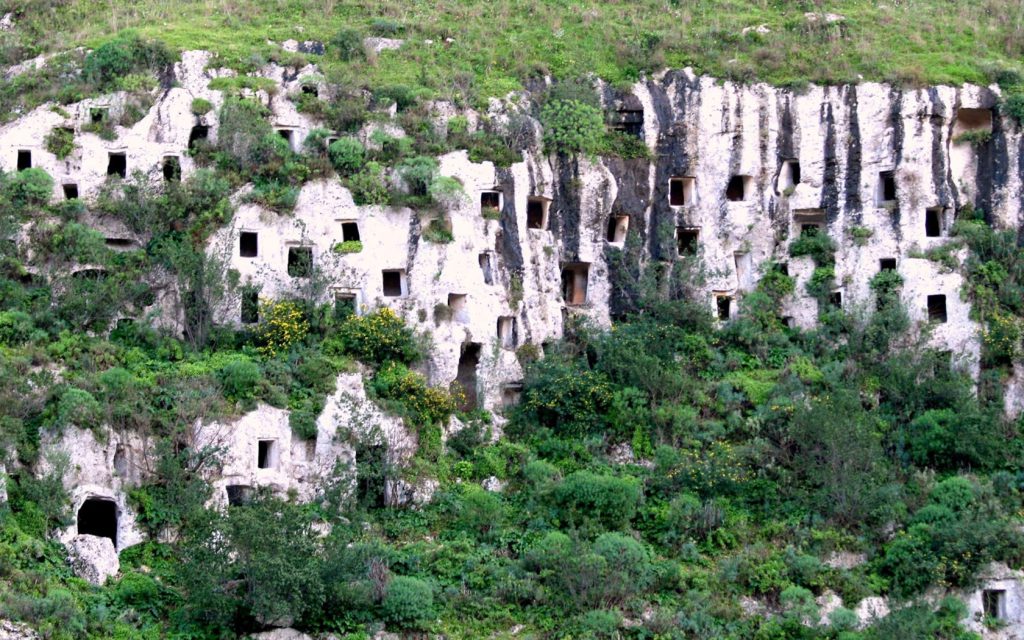

We returned to where we’d left the car, parked above the stepped limestone terraces along the rim of the gorge. From here it was easier to see the countless rock-cut tombs of the Filipporto Necropolis.

We moved on, then turned off the road again at a signpost for Anaktoron.

Off the road, further on, a track leads up to the top of the hill and the so-called Anaktoron, or Palace of the Prince, a megalithic building dating from the Late Bronze Age, only the foundations of which survive; it was the only stone construction in the settlement. Nearby are short sections of wall and a defensive ditch, the only remains of the city, recently identified with the legendary Hybla, whose king, Hyblon, allowed the Megarian colonists to found Megara Hyblaea in 728 BC. Far below, the Anapo Valley can be seen, with a white track following the line of the old railway… There is a view of Sortino in the distance. In the early months of the year, flocks of ravens can sometimes be seen here, performing a mysterious mating flight, almost like a joyous dance, during which they fly upside down and link feet for a moment.

Modern ruins amongst the ancient ones.

Freshly pruned apple trees.

This is a place of remains and excavations.

A lonely road leads from Ferla for 12km along a ridge through beautiful remote pastureland and pinewoods to the extraordinary prehistoric necropolis of Pantalica, in deserted countryside, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a nature and archaeological reserve run by the Azienda Forestale. All around rock tombs carved in the cliffs can be seen. The deep limestone gorges of the Anapo and Cava Grande rivers almost encircle the plateau. It seems as though the inhabitants of nearby coastal settlements such as Thapsos settled in this naturally defended site in the 13th century BC. The cliffs of the vast necropolis, one of the largest and most important in Europe, are honeycombed with many hundreds of tombs of varying sizes.

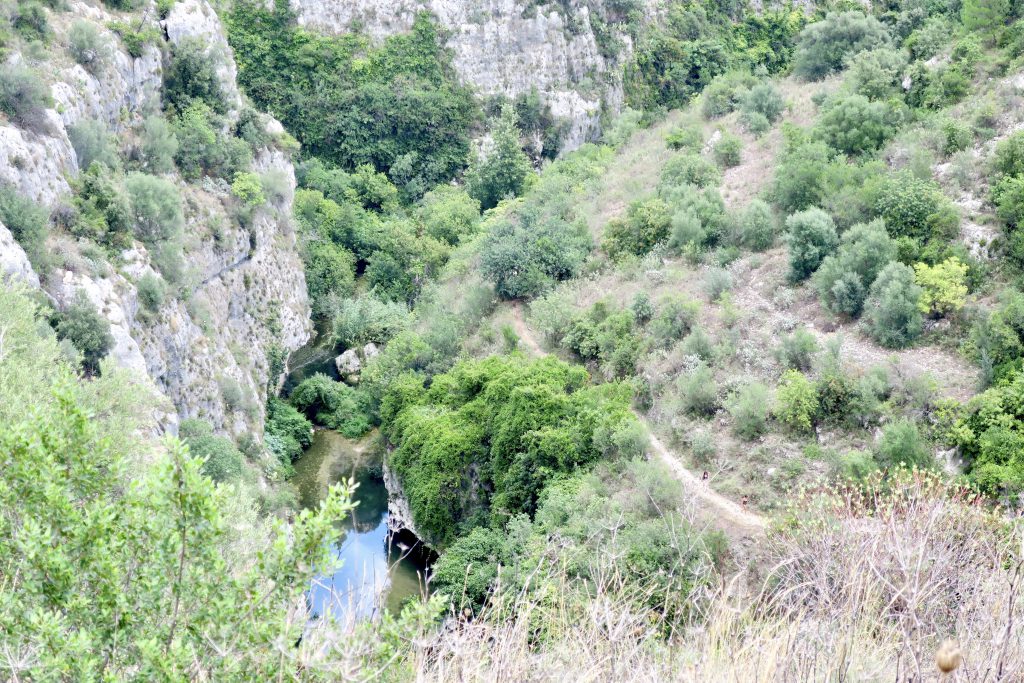

We continued down the road, aware that it was about to run out and we would soon have to turn back. At the next hairpin bend we could see cars up ahead parked in the road, a sure sign there was nowhere else to park, so we pulled off the road and followed a path to a belvedere on the edge of the gorge.

Our friend the stone cricket showed us the way.

We caught sight of more rock-carved chambers in the cliffs below

and fleeting glimpses of the river and the cries of bathers jumping in.

It seemed a long way down and quite out of reach. It was getting late and time to turn back.

The Hermit showed us the way.

※

We drove away along the edge of a gorge, I’m not sure which one, there seemed to be so many, and everywhere the limestone cliffs, perforated with cut-out empty sockets, stared vacantly back at us.

We’d not gone far before we were halted by a group of oncoming cows exercising their right to roam, and I remembered the guide book: and small herds of cattle wander around apparently untended.

They passed by calmly, some more inquisitive than others. This was obviously their road.

With their blessing we continued on our way. Our increasingly winding way, on a surprising and exhilarating series of tight bends around the outskirts of Cassaro. This was not the way we had come.

Eventually we found our way safely back to Ortigia…

※

Now as I write this, almost two years later, sitting at my computer I can revisit Pantalica via Google Maps, and to my surprise and dismay I realise we turned back just short of Paradise. If we’d left the car where it was and continued around the hairpin on foot, past all those parked cars, it would have been just a short walk along the road to where it ends at this small car park, and then down the path.

Google Earth shows the convergence of the Cava Grande and the Anapo rivers, two deep canyons meeting just below us. The path leads down to the water’s edge, with the promise of tree-shaded pools and gentle cascades, and in the cliffs above, all the magnificent rock-carved windows of Pantalica.

Surrounded on all sides by deep gorges and accessed by an eleven-kilometre road that terminates here, Pantalica is the largest prehistoric cemetery in all of Sicily and its 5,000 rock-cut tombs make it an essential place to visit. Initially populated by those fleeing from Thapsos, Pantalica’s remoteness and inaccessibility was clearly its appeal. Indeed, no visitor could imagine sustaining an attack on such a Shangri-La. The deep Anapo Valley at the south winds right around three of Pantalica’s four steep sides, an almost equally deep tributary valley shoring up defences at the north. This, however, did not deter the ultra-paranoid population from digging a defensive ditch all along the northern ridge. The long-term success of this remote spot is evident from its rock-cut Byzantine church, which was built during the spur’s reoccupation in the early 8th century CE.

Julian Cope: The Megalithic European

How wonderful it would have been to wander there, to view the verdant riverbanks through ancient hand-carved window frames. A lost romantic idyll, now become strangely ironic when seen from our present vantage point. In the grip of a global plague we’re once again cast out of Eden, with little time to bury our dead in cut-outs high up under the sky. These days we leave the Earth much too quickly.

※