I was born just after WW2. My parents had moved to Noke when they married in the early 1940s. We lived in a tiny cottage, totally lacking modern amenities. No electricity, water from the well and an earth loo in ‘The Elm Barn’, a shed with a grand name, all set in a third of an acre of orchard. An artist’s retreat from the hurly burly of war torn London. This was my world. Apple trees to climb, a stream to splash in, and a duck pond beyond the gate where my brother and I sailed catamaran boats whittled from elder sticks.

The village was a place apart. A road petering out on the edge of the moor, smelling of cows and cow parsley, deep ditches fringed by pollard willows and a huge sky.

This is the place my life started. The map of it imprinted on my psyche in the way that a nest site is fused into the brain of a swallow. However long since I was there, on returning I know I am home. A place of huge skies and wet meadows. Meandering waterways and deep hedges divide the ground unchanged since recorded in the Doomes Day Book. Thick clay. Rooks rattling the bare branches of Prattle Wood. Threading high clouds, a drone woven by a small airplane.

More than half a century since I slept in the cottage bedroom. The broody squabbles of chickens break the dawn stillness. A trapped tortoiseshell butterfly flaps on the tiny window pane. Wattle and daub walls and thick thatch. Downstairs the warmth of last night’s fire lingers in the silver wood ash.

The moor was always beyond the familiar. A landscape of myth and wildness. Damp stretches of rough meadow tufted in course clumps of grass. Old ditches needing to be cleared, fences replaced, hedges replanted. An abandoned waste patrolled by wild cattle. The clay pocked by unexploded bombs from it’s time as a practice bombing range from the war. Somewhere too dangerous to venture. The war scarred my brother. He was bombed out of London. Had nightmares from the blitz noise. The low front door had a small square window fitted with a bomb sight dating from WW1. My pacifist parents, somehow apart from, yet deeply marked by those five years. Nettle Soup.

Otmoor retains an essential separateness. There is still a military rifle range. It’s rapid rattle signalled by the red flag limp on the pole where the Roman road enters the moor. More though is now bird reserve. Still kept apart to allow the birds to roost and feed. We humans fenced off with designated viewing spots.

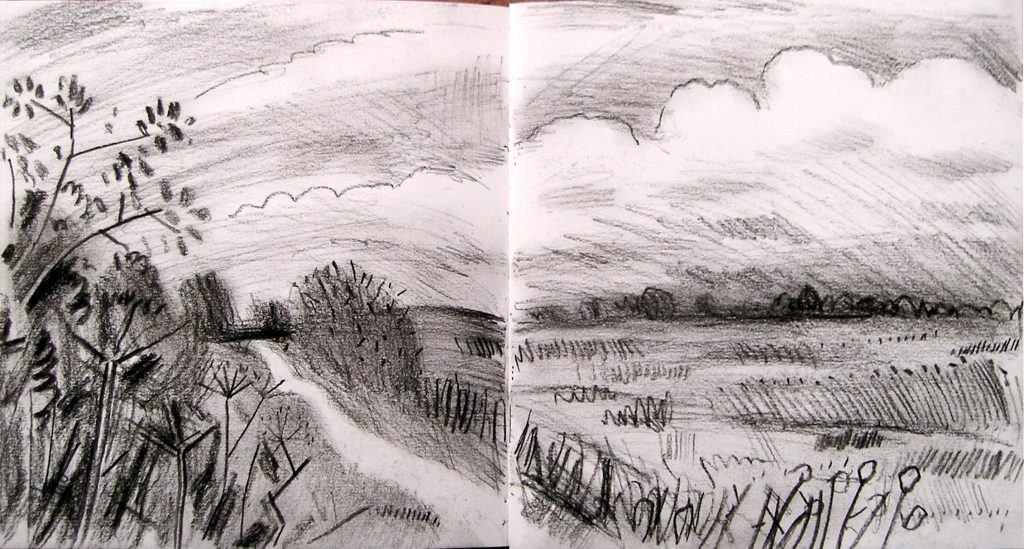

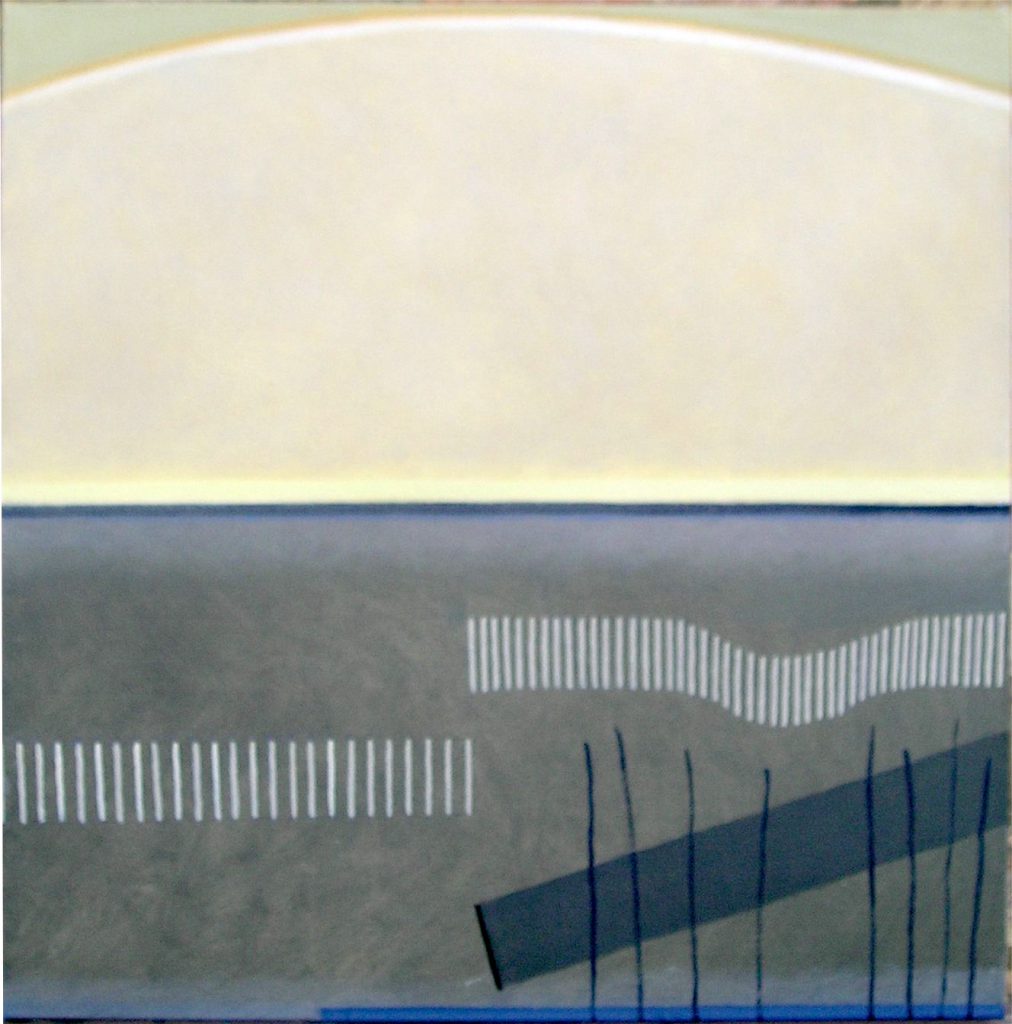

Trudging the boundary track I look out at the new-made moor. Lines of reeds catching shafts of sun. Flocks of geese called to each other as they graze. A black and white flutter of peewits rise and fall in the winter sun. Reed buntings, marsh harrier, white egret, ducks this and that. I was a bird spotter as a boy. Now most forgotten. I walk the paths to see the light, note the quick shifts of colour, search out a spot to return to and set up my easel. Mostly I just look. Absorb some quality that is best not defined, later to be rebound in layers of paint on canvas back in the studio.

The most risky work is done ‘en plein air’. When I return to that spot which offers something I might be able to transcribe with oil paint on board. Two or three hours and the sun’s place in the sky has moved. Clouds scud past. Rain threatens. I paint with a kind of hypnotised fury. Then pack all away and retreat to home and look at what I’ve done. If the weather repeats itself I might get back the next day and rework, refocus, repaint. Most often not. There is a risky rightness to these images when they work. A gamble. If it pays off something special has been transcribed, translated. Half a dozen times in a summer if I am lucky. But this activity is how I access my long connection with this strange place.

For the past two years David Attwooll & I have made Otmoor the focus of a project. We set aside some time to explore. Two ways of connecting with experience. We talk, photograph, poke about in churches and barns. Tell stories.

Otmoor

(i)

a tightening tide felt

here in the country’s navel

a hundred miles from the sea

no hierarchy of land

and water compounded

indeterminate wetland

the landscape inverts

subject object

seeps into language

light skids off a ditch

in a brisk wind

a flit a marshy hollow

a pill quaking bog

in the old course

the River Ray misses

blurred calligraphy reeds

layering of sedges

rushes coarse grass

a kind of openness

something gone away

brought back again

(ii)

at the moor’s edge

a red-eyed radio mast

the hill’s exclamation

broadcasts through space

near the moor’s hub

a huge ammonite lies in the mud

her spiral has listened to time

for sixty million years

(iii)

waterbirds rehearse

their repertoire of impressions

felt mallets

striking a marimba

ricochets from a 50’s

cowboy shoot-out

small waves scuffing

a wooden hull

the sound of a pattern

intricate and oriental

chatter of circling stars

in daytime when no-one sees

© David Attwooll 2016

Our paths have led to different places. David has enriched the time with narratives and myths and research weaving a complex poetry, rich with a thick history. Human stories told in spare and vivid rhythm.

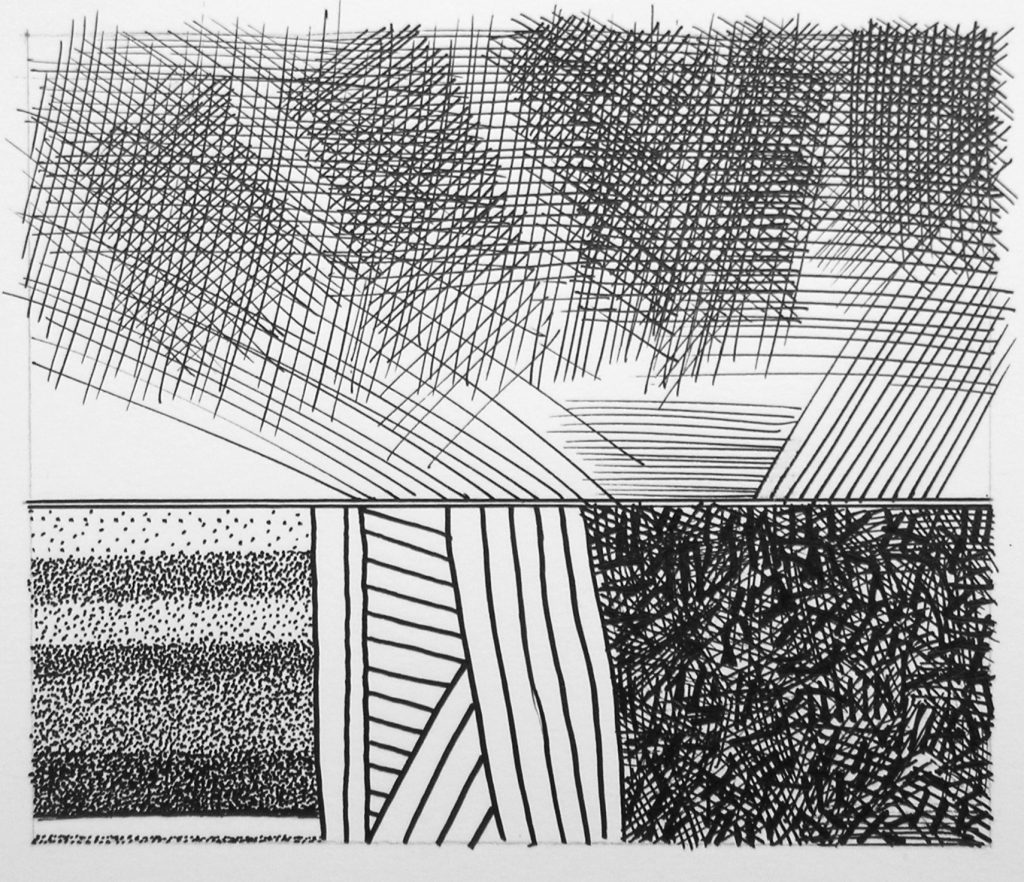

I have taken another road. Robert Frost tells …long I stood and looked down one as far as I could to where it bent in the undergrowth. I have ended making images stripped to essentials. A horizon line. Up and down. A scraped surface. A distant blue grey. A scene waiting to be inhabited. A polar opposite to David’s writing. I think they complement each other but cannot be sure. The process remains a chancy mystery.

※

The new exhibition of paintings and drawings, both figurative and abstract, by Andrew Walton titled OTMOOR : MOONLIGHT & MYTHS runs until 29 May at Art Jericho, Oxford. Walton’s exhibition is a response to two years’ walking across Otmoor with friend and poet David Attwooll.

Andrew Walton / The Rowley Gallery

Inspiring work Andrew. I love the way your work, no matter if it is representational or abstract, is always about observation.

Thank you Paul. Your insight that it is always about observation is quite right. If out painting plein air the question, as you know, is “What am I seeing & how do I select the elements which translate into a painting?” When I work in the studio I am observing what happens on the surface of the painting or drawing. I am not really referring directly to a memory of a view. The image somehow comes round to a kind of connection, but always visual. I am not a conceptual artist. I make images that I guess are to do with loving looking at stuff, also just delighting in the materials we use as artists.