For one week in May this was our bedroom window, with its view of the Golfe de Calvi and the mountains beyond, with Monte Grosso 1,938 metres and Monte Padro 2,393 metres, two of the highest in Corsica. Every morning their silhouette was gradually illuminated as the sun rose behind them, projecting fast-moving cloud shadows onto their faces, with every morning a different view.

This morning they were smiling, inviting us to explore the land between the mountains and the sea, the region known as the Balagne, the ‘Garden of Corsica’ according to the guide book.

In 1898, the Balagne was lovingly described by the traveller Ardouin-Dumazet in his Voyage en Corse:

“Thanks to the care given to the olive groves, this ample and luminous valley, open between superb mountains, gives an impression of richness like no other place on earth. The two cantons of the Balagne fertile, Belgodère and Muro, are the most beautiful in all Corsica. The sinuous corniche road traced over the flanks of the hills, from Belgodère to Muro and Cateri, is a perpetual enchantment.”

Corsica: Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls

Out on the terrace I got a good morning flypast from a welcoming grasshopper, up over my head and onto the roof for a better view. It seemed like an auspicious start to the day.

We headed east towards the mountains, through Calvi’s hinterland and into the Balagne. Our first stop was Calenzana, ‘now known for its wines and cheeses, and as the starting point of the GR20 and the Mare e Monti trail’. We parked in the square between two churches and went into the smaller one.

The Chapel of the Holy Cross Brotherhood, home to the Confrérie Saint Antoine Abbé.

This northern escarpment of the Niolo is one of the most secret areas in all Corsica, practically waterless, shunned even by the shepherds. As we approached it I could see dark valleys disappearing into rocks, pathless and uninhabited. Yet Calenzana, standing so close under the mountains that one could catch the aroma of the pines, was a much larger place than any we had passed that day, almost a town, laid out round its imposing baroque church and campanile overlooking the graveyard of five hundred Germans, allies of the Genoese, killed during the national rebellion. The inhabitants, too, looked urban; in fact they are said to rule the gangster hierarchies of Marseilles, emigrating there generation after generation just as young men in other villages of the Balagne regularly enlist in the army, the merchant marine. At all events they are ‘not of the flour that makes the host’ – the bread of the Eucharist – to use a local expression; if one enters the cafés one is likely to meet with the hooded stares of expensively dressed men with gold-ringed fingers busy at the card tables; once I blundered, unwelcome, into a curtained alcove where the game was unlegalised baccarat. Others are hunters who alone know the topography of Monte Grosso, where they vanish in contempt of the law to stalk moufflon, the strictly preserved, fast disappearing curly-horned Corsican wild sheep, delicious forbidden eating. Calenzana belongs only geographically to the serene, squirearchical, outdated, Italianate Balagne; almost the last village before the sixty-mile-long no-man’s-land of untamed maquis rolling south to Porto, it is linked, in a wary, competitive intimacy with that other outpost, seabound Calvi.

Dorothy Carrington: Granite Island, A Portrait of Corsica

– published 1971, but written during the previous 20 years.

Across the square from the chapel stands the much grander Église Saint-Blaise de Calenzana.

The church of St Blaise is of astonishing proportions with much polychromatic marble inside. The black-and-white tiled floor sloping towards the west door ‘Let’s the water out when there’s a flood from the mountain’, the Monte Grosso, a local informed me. The polychrome marble altar is 1767. There is some cunning trompe l’oeil of 1880 and medallions around the ceiling of the 18C nave depicting St Blaise.

1km from Calenzana is the church of Ste Restitute, Corsican martyr beheaded in 303 on the orders of the Emperor Diocletian.

Roland Gant: Blue Guide Corsica

A statue of St Restitude of Calenzana and, below, a reliquary containing her bones.

On the winding road out of town, at the Chapel of St Restitude, a fallen wayside serpent.

The next stop was Zilia and the Église St Roch. We hadn’t set out to make a tour of the churches of the Balagne, but because there’s one at the centre of every village and their doors are nearly always open, it seemed only right to call in and pay our respects. They’re the region’s free local art galleries.

A Communion of Saints

The road passes between the church on our right and a belvedere to the left, at the edge of the village where the land falls away with a spectacular view down to Calvi airport and north to Montemaggiore.

And a similar sweeping panorama, when we get to Montemaggiore on the crest of the headland, looking back down to Calvi and the Golfe de la Revellata beyond, and I can see the Citadel and I imagine I can see our house and our bedroom window, and I can see me looking back at me.

The road below falls away like a waving ribbon and as we look on a procession of Citroëns, ancient and modern, goes weaving around the corniche hairpins – 2cv, Dyane, Traction Avant, Mehari, DS21 – I really should’ve taken photographs of these beauties – Vintage Citroën Corsica.

Another church and another campanile, they all seem to be variations of the same baroque model, but Montemaggiore is closed. So it’s back to the car, wishing we’d hired a Citroën instead of a Peugeot.

But glad we’d not hired a parapente.

We were stopped in our tracks by the amazing view and imagined paragliding from the Col de Salvi.

At 500m along the D 151 from Catteri take the D 413 to Sant’Antonino, on a ridge between two valleys. Founded in 9C it is perhaps the oldest village in Corsica. Narrow cobbled streets, tall granite houses, its church and a chapel are set below on a greensward which serves as a car park.

Roland Gant: Blue Guide Corsica

One road goes up from Cateri to the Col di Salvi and Montemaggiore; another ascends, just north of the Cateri crossroads, to Sant’Antonino, the most perched of all the Balagne’s ‘villages perchés’. Founded in the 9th century by the Savelli counts of the Balagne and claiming to be even older than Corbara, Sant’Antonino is a web of narrow, winding vaulted lanes and steps (one carved with an ancient nine-men’s morris game), tall granite houses and a pair of Baroque churches, all crammed on a rocky pedestal that usually turns an un-Corsican yellow by June. As Corsica’s ‘Most Beautiful Village’, according to the plaques, it also gets many coach parties.

Corsica: Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls

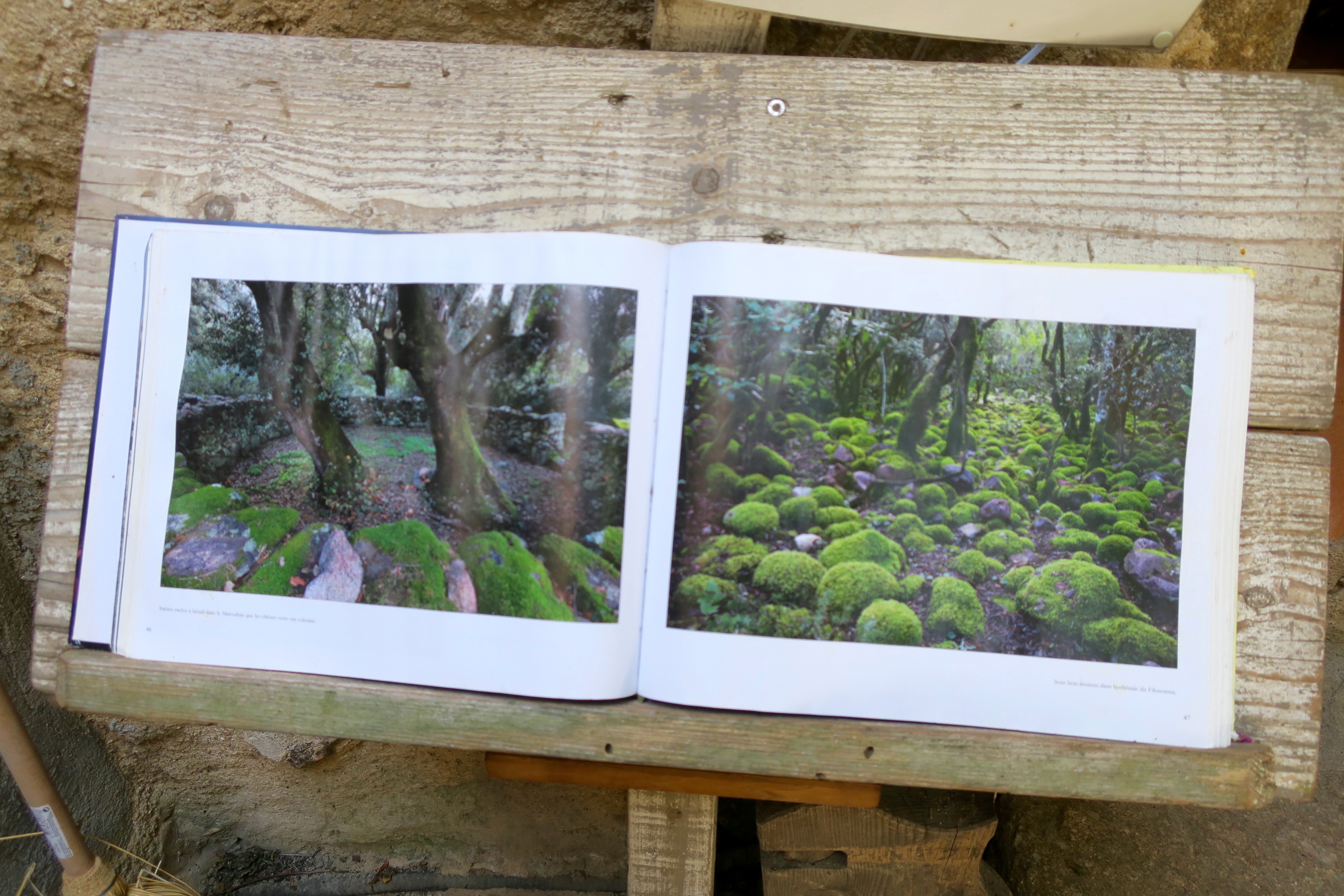

The villages were glimpsed kaleidoscopically as the bus meandered to Calvi through the old gnarled olive groves: below the road, as a geometry of Roman tiles, and above as compact cliffs of superimposed facades gashed by dark archways and arcaded galleries. The silver crowns of the olives fluttered over the shelving miles to Algajola, collapsing Genoese fortress jutting into the waves; Sant’Antonino brooded over us, a circular medieval village that from afar looks like one great castle, something on the lines of Krak des Chevalier.

Dorothy Carrington: Granite Island, A Portrait of Corsica

And because it’s there we take a quick look inside the Church of the Annunciation.

Another auspicious grasshopper.

Sant’Antonino is a maze of narrow cobbled lanes, ginnels and alleyways climbing between granite walls to the top of the village. The highest house is no.1 then down to no.2 and so on winding back through the labyrinth to A Casa Corsa for lunch, and all the way spectacular rooftop panoramas.

From Sant’Antonino we descended to Aregno, a sleepy village with no-one on the streets and no open doors. The Church of Saint-Antoine-Abbé was firmly shut. So we climbed a little way back up the hill.

La Trinità San Giovanni Battista is a 12C masterpiece of Pisan Romanesque architecture.

Four great walls of multicoloured granite blocks, decorated with curious carvings,

it’s a surprisingly modern-looking building despite being almost a thousand years old.

Striking polychromatic walls of granite ranging through dark green, shades of yellow, orange and ochre. Bold sculptures in high relief on the western front: left of the door a woman in a long dress, hands on hips, wearing a small cap; to the right a naked, bald man (Moses?) holding what might be the tablets of the law on his knees. Under the apex of the pediment is a seated male figure with the ankle of his left leg resting on the knee of his right in ‘removing thorn from foot’ posture. The door was originally surmounted by a low rounded arch without a tympanum, replaced in late 19C restoration by a monolithic lintel. The ‘teghie’ (flat stones) covering of the nave has been replaced by round tiles but has been retained on the roof of the semi-circular apse.

An admirably bare single nave. Two frescoes on the north wall. The first represents ‘Quatre Docteurs de l’Eglise latine’ (Augustine, Gregory, Jerome and Ambrose) dated 17 May 1458, probably the work of a local artist because Jerome, for example, is given in the Corsican form of Gilormi. The second fresco is dated 1449 and depicts St Michael slaying the dragon, his expression that of a matador confident of tail and ears.

Roland Gant: Blue Guide Corsica

Next stop Pigna and the Church of the Immaculate Conception.

The pillars inside are hung with curious Stations of the Cross made out of pebbles.

2.5km north of Aregno is Pigna to the left of the D 151, its houses tightly grouped in narrow paved streets on a rounded hillock girded by orange and lemon groves and olive trees. Exceptional views over to Algajola Bay, particularly at sunset. Park in square on entering the village. The 18C church of l’Immaculée Conception has slender bell-turrets with cupolas at either end of the facade and a fine organ by Antonio Ferrari… In this lovingly preserved Balagne village the true heart and spirit of Corsica is everywhere apparent and available to the visitor – the past still living vigorously, the present actively creative in arts and handicrafts, all adding up to an optimistic and constructive view of the island’s artistic and economic future. In 1964 La Corsicada started here as a co-operative association with the aim of reviving old village crafts with an apprentice system to ensure that ancient skills, some nearly lost forever, are revived and taught to future generations of craftsmen. In the village, together with shepherds and farmers, are potters, engravers, a print-maker, an organ-builder, a maker of lutes and other ancient instruments, sculptors, painters, musicians, specialists in Corsican products and cooking. The Casa Musicale, in a spacious and restored old house, is the village arts centre where several concerts are given each week, with traditional instruments such as the cetera (cithern in English) the medieval lute-like instrument now being made in Pigna, and with the participation of visiting folk and jazz musicians. These concerts, usually given out of doors with the setting sun and sea as backdrop, are unforgettable. In summer a bar and restaurant specialising in Corsican and Moroccan dishes is open in the Casa Musicale (the Casa is closed Jan and Feb). Galleries and studios where work (for sale) by local artists is always on show, including that of the painter and sculptor Toni Casalonga who, among his many activities and exhibitions throughout Europe, has been arts advisor to the Corsican Assembly.

Roland Gant: Blue Guide Corsica

At A Casarella we enjoyed an ice cream on the terrace and a spectacular panorama.

Navelwort Umbilicus rupestris

Then down the coast road back to where we started from…

and another view of where we’d just been.

One thought on “La Balagne”