This interview originally appeared in the London Group Newsletter.

JL – We share in common a childhood in Essex (with parents moving out from London). Do you think that growing up in this semi-rural / suburban environment has influenced your work, or experiences as an artist in general?

DW – I was brought up on one of the first sprawling council estates to be built in Essex, in the also newly built Basildon New Town. But we were surrounded by countryside and spent all our free time as kids outside, summer and winter. I remember there were special mysterious woodland places, special trees and streams that you grew up with so I suppose this may have had an influence.

JL – Do you have any artists in your family? Were your family behind your decision to pursue art as a career?

DW – My daughter recently researched our family tree going back to the 19th Century and sadly there was no trace of anybody remotely connected to the arts. They were mostly from the East End dockland area too busy staying out of poverty. I seemed to have come out of the blue as an artist. I don’t know where it came from but it seemed to take hold from my early teens almost beyond my control. My mother was always supportive but had no real inkling of what went on. My father though was absolutely against it and he expected me to leave school early and bring in another wage. But ironically in very late life, despite his aversion to my art, started to paint himself making naive Alfred Wallis type pictures of local places. Even to the extent of the local paper publishing an article about his work with the headline “Father follows in son’s footsteps”.

JL – You began your art school career by studying in Colchester – how was your experience here?

DW – Colchester was a small, independent proper art school and I spent two years there before going to St Martins. We worked in large wooden huts. I loved it and it was a very formative time. We were totally immersed in art with some very influential teachers such as John Carter, Richard Bawden and John Nash, Paul Nash’s brother.

JL – Which artists – historical or contemporary – have influenced you over the years?

DW – Which artists have influenced me! So many artists have been very special to me over the years; Matisse, Miro, Bonnard, Van Gogh etc. But for a real direct influence I would probably go with my friends and contemporaries such as Jeff Dellow, Clyde Hopkins, Graham Crowley, who I’ve taught with, exhibited with and shared all the ups and downs of making art. Some contemporary landscape painters have interested me such as Michael Honnor, John Virtue and Michael Porter.

JL – You make your drawings outside as opposed to in your studio. What are your motivations for this?

DW – Most of my work on canvas is made entirely in the studio. The works on paper made outside are an important gathering of information, and are part of the process of absorbing the landscape. But I would never work directly from a finished drawing as it would become a process of imitation losing that initial spark and feeling of uncertainty that the studio paintings need. I regard the work made outside as a more direct, intuitive response to what is in front of me as opposed to the more manipulated, slowly evolving studio paintings. It is the experience of working outside that I love as much as the finished product.

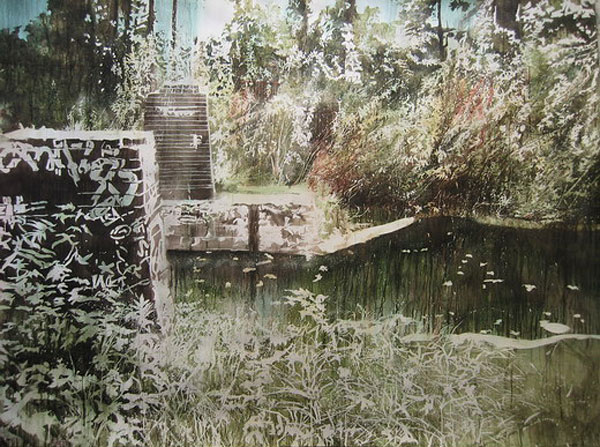

David Wiseman: Waters Edge – Glowing Light

JL – You describe your paintings as “playful but not necessarily topographical”. How would you describe the balance between the importance of representing a landscape in some way and the process of mark-making / exploring material qualities in your work?

DW – I have come to the landscape from a history of abstraction so I have an overriding feel for and love of paint. I like the paint to turn into the landscape. I love the act of painting, to throw the paint on, dribble it, wipe it away, roll it on with rich texture, sponge it on etc. Although I have particular special places in mind, the paintings are not really planned. I start out with a series of marks and see where the painting takes me. I like Jim Faure Walker’s quote on Heron “as if the painting was in command and of course this is what it feels like to be absorbed in a painting. It takes you outside of yourself, your identity dissolves into the painting.”

JL – You’ve made a number of public artworks. How important do you think it is for artists to engage with public art projects? Have any been more challenging or rewarding than others?

DW – For about 15 years I completed a series of large scale public artworks. Many artists in the past such as Matisse and Miro made public art and both had a big influence on me. The importance of public artworks is obvious especially in places such as hospitals where they can be positive and uplifting. But it doesn’t suit all artists and often the practical difficulties are the most challenging. They are time consuming and although I loved all of them, I do think my studio work suffered and it really took off again after I had made the last one.

JL – What, for you, was the driving factor behind joining The London Group?

DW – I absolutely love The London Group. It has always been in the background of my art making over the years. I have been taught by, taught with and exhibited with many past and present members of the Group and have exhibited in a number of open exhibitions over the years. I love the Group’s links to artists of the past and its ongoing aim to be diverse and challenging. I was pleased and proud to be elected somewhat late in life.

JL – If you could have a two person show with any non-living member, including a dinner and a chat, who would you choose?

DW – It would have to be Patrick Heron. I have always loved his work in all its various guises and his writing has always inspired me. I met him a few times when teaching at Winchester and I couldn’t think of a better person to share an exhibition and socialise with. My second choice, if I am allowed one, would be Ivon Hitchens whose work is probably more closely related to mine and would be wonderful to exhibit with.

Juliette Losq: Broken sentences and forgotten names wink like fossils among the ruins