After a trip up north to see my folks it seemed like a good idea to see some folk art on the way home. We’d missed British Folk Art when it was at the Tate, but now we had a second chance.

Compton Verney is an 18th century house in Warwickshire, set in parkland landscaped by Capability Brown. In 1993 the house was bought by the Peter Moores Foundation and in 2004 it was opened as an art gallery. An Untitled Boulder by John Frankland was installed in the grounds.

※

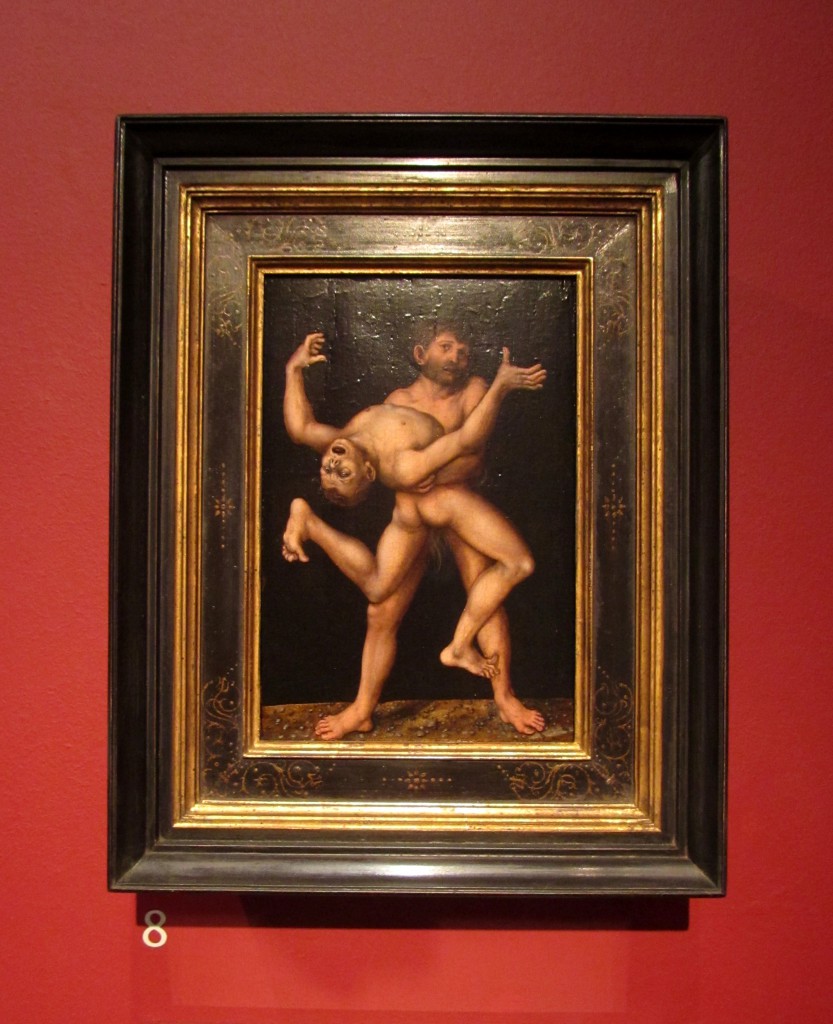

Inside, there are collections of Neapolitan art, Chinese art, Tudor portraits and Northern European art from 1450-1650. This one, No.8, is Hercules & Antaeus, oil on panel, by Lucas Cranach, c.1530.

Lucas Cranach, Venus & Cupid, oil on beechwood panel, c.1525.

Martin Schongauer, ‘Maria Lactans’, Virgin & Child Crowned by Angels, oil on panel, c.1470.

Unknown Artist, Three Female Saints, oil on wood panel, c.1490.

The saint holding the tongs is Saint Apollonia, patron saint of dentistry, a martyr to her teeth.

※

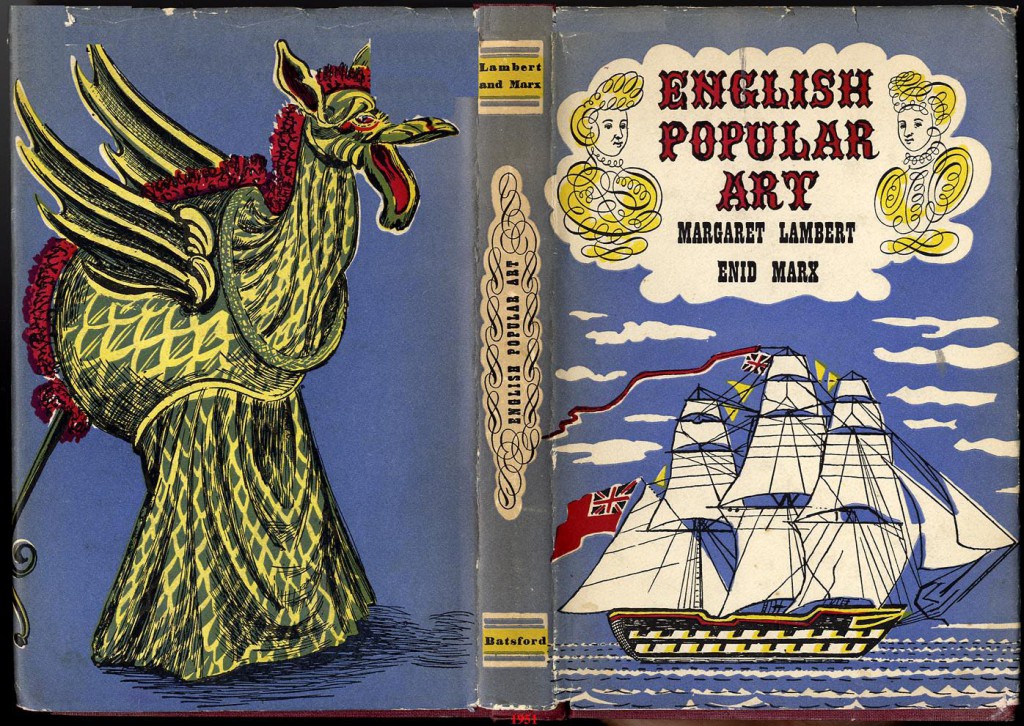

Upstairs there’s a small display devoted to the designer Enid Marx. She was an author and illustrator of children’s books, a book designer, a printmaker, a textile designer and a painter. There are also pieces of folk art and popular art that she collected with her partner Margaret Lambert.

A pair of Victorian cast iron Punch & Judy doorstops, hand-painted by Enid Marx.

Eric Ravilious, Coronation Mug, Wedgwood transfer-printed cream earthenware, 1937.

※

Compton Verney has the largest collection of British folk art in the UK.

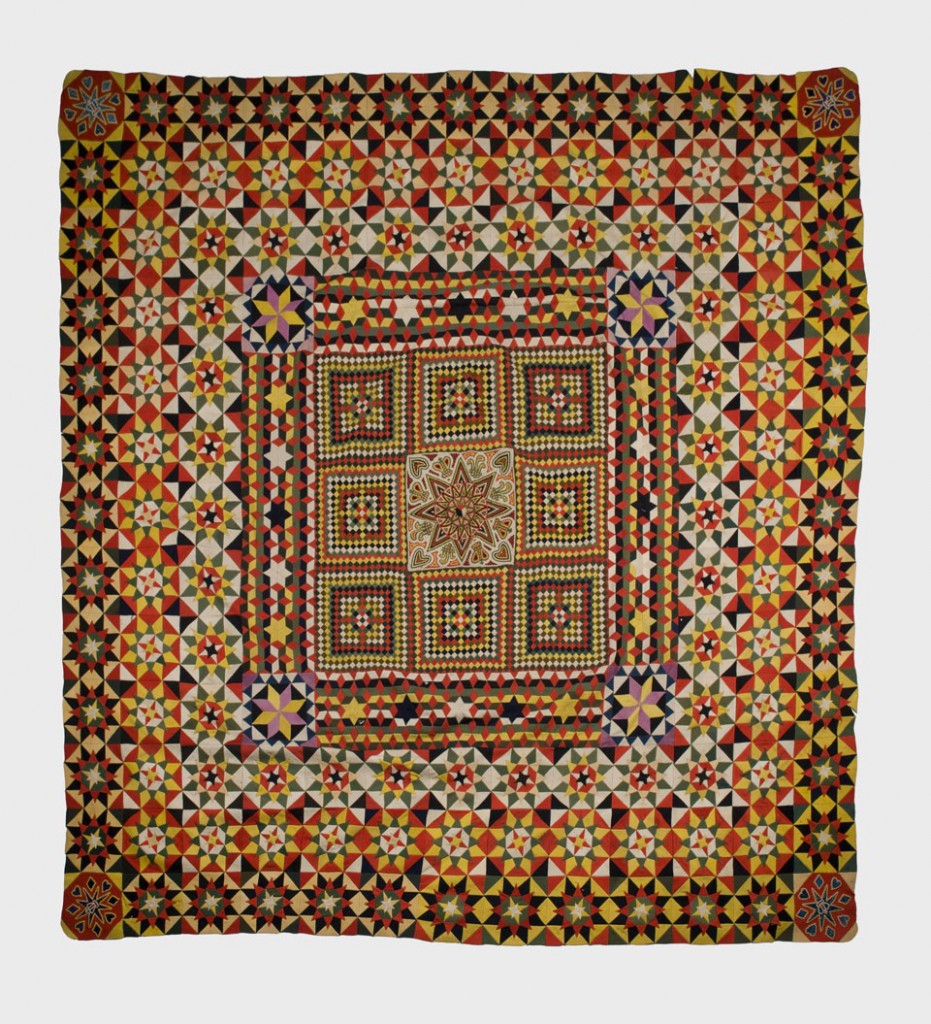

Military Patchwork, British, between 1854 and 1876.

The Fleet Offshore, English School, oil on panel, 1780-90. Blue-Painted Side Table, early 1800s. Primitive Windsor Armchair, Welsh, elm & ash, 1700.

Alfred Wallis, Schooner Approaching Harbour, oil on metal tray, c.1930.

※

The main galleries at Compton Verney are hosting British Folk Art until 14th December, an exhibition organised by Tate in collaboration with Compton Verney. It includes pieces from Compton Verney’s own folk art collection. Photography was not permitted so I gleaned a few images from the internet.

Ships’ figureheads and other carvings are among the most longstanding genres of folk art… (they) should have expired with the vessels that bore them, but figureheads were salvaged from stranded or wrecked ships, or preserved as retired ships were disassembled at the breakers’ yard. Brought permanently onto land, they were cherished as souvenirs, curiosities or, indeed, sculptural artworks, re-purposed as shop signs or in the case of figures salvaged from wrecks, set up as memorials. They were thus preserved, but also transformed.

The painted, carved or constructed signs hung in the street outside shops and businesses to advertise the services or goods available within, before the general spread of literacy and of standardised street numbers, are among the most long-established forms of folk art.

Sun Trade Sign, c.1720, cast iron & paint, Museum of London.

This is an early surviving example of a trade sign. Made from cast iron, it takes the form of a beaming sun with a face… ‘The sign of the “Golden Sun” between the two first-floor windows of 146 Whitechapel High Street, is doubtless intended to represent the head, surrounded by beams of light, of Apollo, the God of Healing, as it appears in the arms of the Apothecaries’ Company’.

Sweetheart Pincushion, 1896, fabric, beads, pins, Beamish Museum.

This exuberant pincushion was made in 1896 and fits into a tradition of such objects, made by soldiers and sailors while on duty, to be sent home as love tokens.

Crimean War Quilt, c.1850-1900, felted wool, Tunbridge Wells Museum & Art Gallery.

Military quilts – made between c.1850 and 1910 from the coloured wool serge or worsted twill used in soldiers’ uniforms – are a fascinating chapter in the history of British patchwork… Quilt-making was vigorously promoted by the British Government as a means to distract soldiers from alcohol and gambling during long periods of inactivity.

Sailors with sewing machines on HMS Hindustan, c.1905, Royal Navy Museum, Portsmouth.

…part of a sailor’s duty on-board ship was to repair sails and uniforms and all serving seamen were required to have rudimentary sewing skills… The sailors stitched their decorative pictures in wool on canvas, with button thread or silk used for more precise finishing… the sailors’ lack of artistic training often lent the ‘woollies’ a certain naïvety, yet their understanding of ships and ship-building is clearly apparent in the accurate rendering of rigging, flags and other details.

Gunner Baldie, Sunbeam, 1875-80, wool & silk on canvas, Compton Verney.

This example, from the British Folk Art collection at Compton Verney, demonstrates how sailors used their skills to create personal tributes to the ships on which they sailed. ‘Sunbeam’ was a 323 ton, three-masted schooner built in 1874. It was one of the first yachts to sail around the world, carrying the railway tycoon Sir Thomas Brassey and his family on their 1876-77 circumnavigation. This picture of the boat sailing up the River Solent was made by Gunner Baldie, a member of the Royal Artillery who probably attended the family on a later voyage.

Alfred Wallis, The Blue Ship, c.1934, oil on board, Tate.

The St Ives rag-and-bone merchant and self-taught painter Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) is the great exception to the general neglect and marginalisation of self-taught and artisan art by the British establishment. His work is familiar to everyone with an interest in modern British art, displayed extensively at Tate and in collections across the UK and internationally.

George Smart, Goosewoman, c.1830, paper & fabric collage, Tunbridge Wells Museum & Art Gallery.

From around 1818, visitors to the spa town of Tunbridge Wells in Kent could, in the midst of the whorl of fashionable shopping and entertainments that made the town such a lively attraction, visit ‘Smart’s Repository’ in the nearby village of Frant. This was the premises of the local tailor, George Smart (c.1775-1845), who alongside his primary business created and sold pictures made from textile scraps.

Unknown Artist, Bone Cockerel, c.1797-1814, bone & wood, Peterborough Museum.

This remarkably precise model of a luxuriously plumed cockerel was made by an inmate at the Norman Cross Depot for Prisoners of War, near Peterborough. In operation from 1797 to 1814, during the long wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France and its allies, Norman Cross was the first modern-style prisoner-of-war camp. It held up to 6,000 prisoners at any one time, predominantly French but with some Dutch men present in the early years.

Unknown Artist, Tin Tray Covered With Boody, tin & broken ceramic, Beamish Museum.

From as early as 1815, the term ‘boody’ or ‘boudy’ appears to have been in common usage in the dialect of Northumberland and Durham to denote a piece of broken china or earthenware. Originally collected by children and classed as playthings, by the 1880s boody was increasingly used to decorate jugs, bottles, boxes and tinplate in a distinctive mosaic style, which became known as boody ware.

I’m reminded of the trencadis at Park Güell in Barcelona, the walls covered with ceramic shards and broken tiles by Antoni Gaudí, that Robert Hughes reckoned was the first instance of collage (and which appeared in an earlier post). Maybe he’d not heard of boody ware.

Unknown Artist, God-in-a-Bottle, 19th century, glass, wood, water, Beamish Museum.

While the ship-in-a-bottle is well documented as a form of amateur craft, the associated God-in-a-bottle, sometimes also known as a ‘whimsy’, ‘patience’ or ‘puzzle’ bottle, is far less familiar. Particularly prevalent in the north of England and often associated with the Irish Roman Catholic diaspora, working in construction or mining, the exact purpose of these enigmatic objects remains a mystery. Perhaps talismanic in nature and used as a form of good-luck charm by some, they were claimed by others to possess strong medicinal powers.

These were intriguing, I wonder how they taste? And there’s lots more. It’s a wonderful exhibition, full of vernacular homemade and handmade authentic artefacts, each with a story to tell. It leaves me wanting to see more folk art, British, French, Spanish, wherever, everyfolk art. Here’s a short trailer…

British Folk Art continues at Compton Verney until 14 December 2014.

One thought on “British Folk Art”