Sudbury is a place we often pass through on our way to somewhere else. But this time we stopped for a closer look and pretty soon we realised we’d already done this walk before. It all fell back into place.

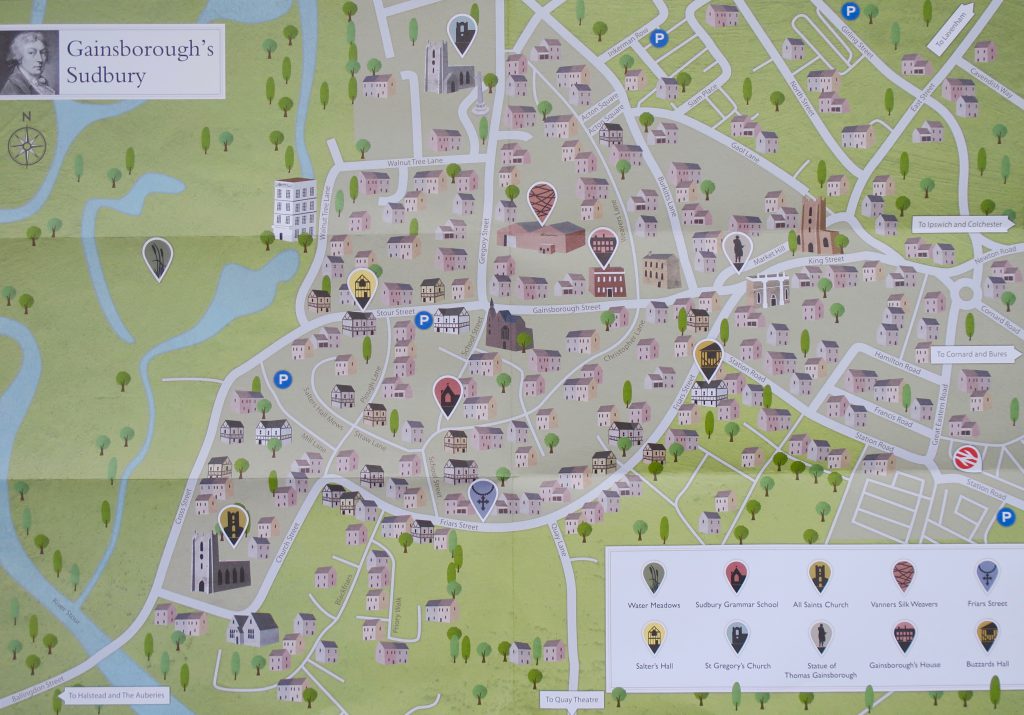

The market town of Sudbury has a unique feature on its doorstep. The Sudbury Common Lands make up some 115 acres of water-meadows on the flood plain of the River Stour. Cattle and horses graze here, as they have for a thousand years, and the area is crossed by footpaths, making it perfect for a peaceful walk.

We started out on the Valley Trail, along the disused railway line to Bury St Edmunds and Cambridge, but we branched off to walk around Friar’s Meadow and got disoriented just like last time, and quickly realised we were going the wrong way down the River Stour.

We doubled back and walked along the meadow’s riverside where girls sunbathed in groups, each group in its own bubble of portable pop music, and across the river boys dived in from the top of a concrete pillbox, whilst in the distance cattle safely grazed. A scene of timeless pastoral harmony.

We got back on track and followed the old railway as it crossed over the river and the road into town, over the allotments, by Kingfishers and Woodpeckers and alongside AFC Sudbury’s football ground.

We continued along the Valley Walk for two miles, crossing over Belchamp Brook and down a green tunnel full of birdsong, until we reached the path that led us between Borley Hall and Borley Mill.

We’d been heading north so far, following the old railway towards Long Melford

but now we turned south and walked back to Sudbury along the bank of the River Stour.

And another riverside pillbox, this one with a fine head of ivy.

We came by North Meadow Common to cross the river at Brundon Mill

and counted thirty swans and more beneath the bridge.

We came down to Sudbury Common Lands where we were greeted by this gentle old horse

standing still as a statue beside the path, enjoying the company of passers-by.

The river divides and follows multiple courses across Fullingpit Meadow and Freemen’s Common.

The water-meadows of Sudbury were first mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. Their current status dates from around 1260, when the Freemen of Sudbury acquired grazing rights from Richard de Clare, the owner of Clare Castle. The right to graze livestock on the commons still belongs exclusively to the freemen, passed on over the generations from father to son.

In the distance stands St Gregory’s Church where the preserved head of Simon of Sudbury is kept in the vestry. It can be seen on request but we didn’t ask. Simon was Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England. In 1380 he introduced the poll tax and in 1381 he was beheaded on Tower Hill in London during the Peasants’ Revolt. His story is told here.

On Market Hill in front of St Peter’s Church there is a statue of another son of Sudbury, the painter Thomas Gainsborough. But it’s market day and there’s a fast food banner on the takeaway van, and just for a moment he’s mistaken for Thomas GainsBURGER.

The artist Thomas Gainsborough (1727-88) was born in Sudbury and as a boy he used to wander the water-meadows looking for inspiration. Both his father, a cloth dealer, and his uncle, who ran the local grammar school, were Freemen of the Commons. It is said that young Thomas would often play truant from school in order to sketch in the countryside. Although he later became better known as a portrait painter, Gainsborough loved to paint landscapes and his society portraits were simply a way of earning enough money to survive.

Gainsborough’s House, in a Georgian-fronted brick building close to Market Hill, has been restored and opened as a museum. It contains the most complete collection of his work on display anywhere in the world, including his first known portraits of a boy and a girl, a miniature of his wife, and some 20 portraits of rich clergymen, politicians and landowners. A small cabinet holds Gainsborough’s personal items, such as his pocket watch, snuff box, pipe stopper and paint scraper. The walled garden, where exhibitions of sculpture are held in summer, contains a 400-year-old mulberry tree.

The sign on the tree says – Here we go round

Hidden away in an alcove, an angelic wall-painting

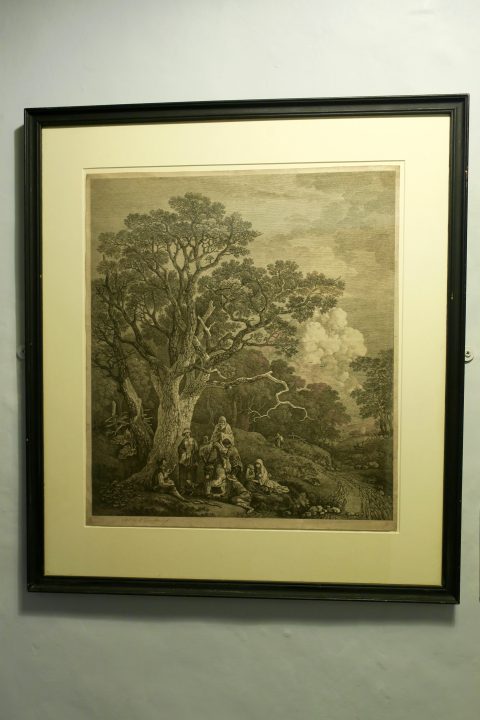

Thomas Gainsborough (1722-1788)

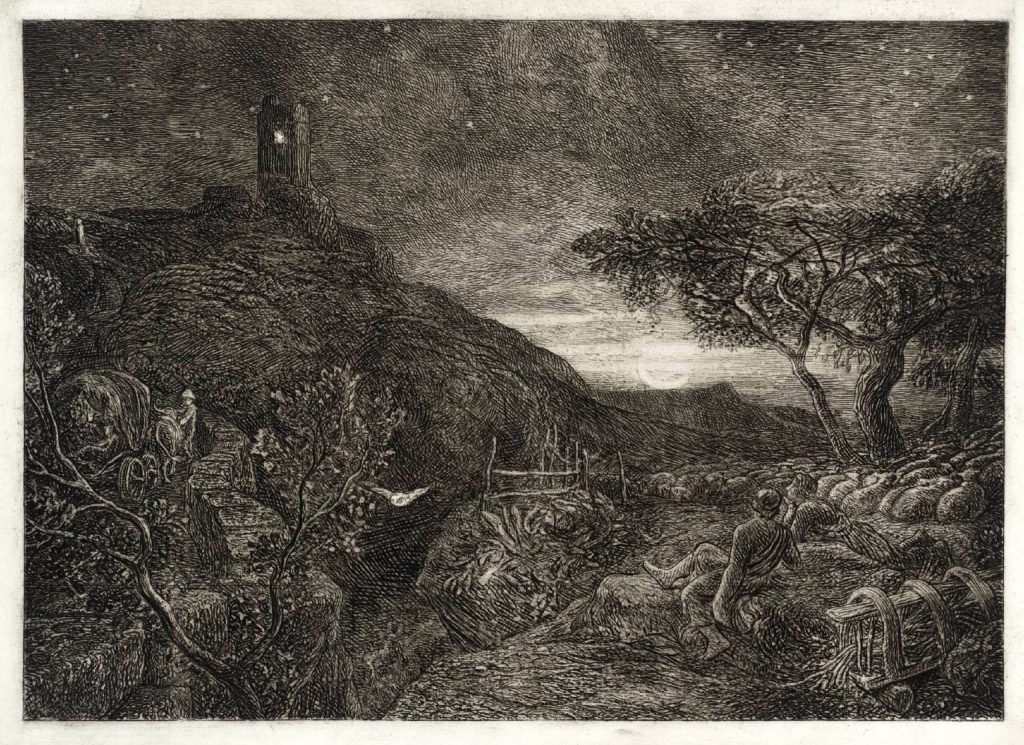

Wooded Landscape with Gipsies Round a Camp Fire (The Gipseys) 1759

etching on laid paper

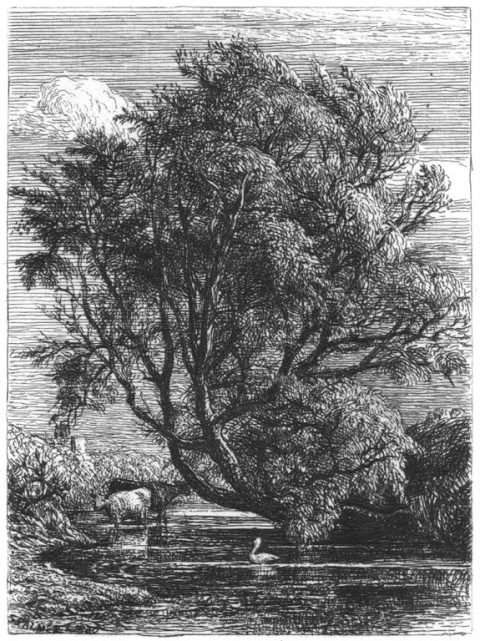

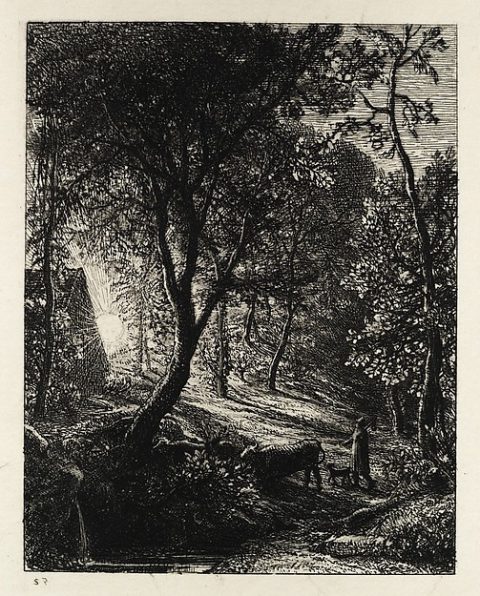

The main downstairs gallery was devoted to a beautiful exhibition of Samuel Palmer etchings.

Poetic Landscape – The Etchings of Samuel Palmer

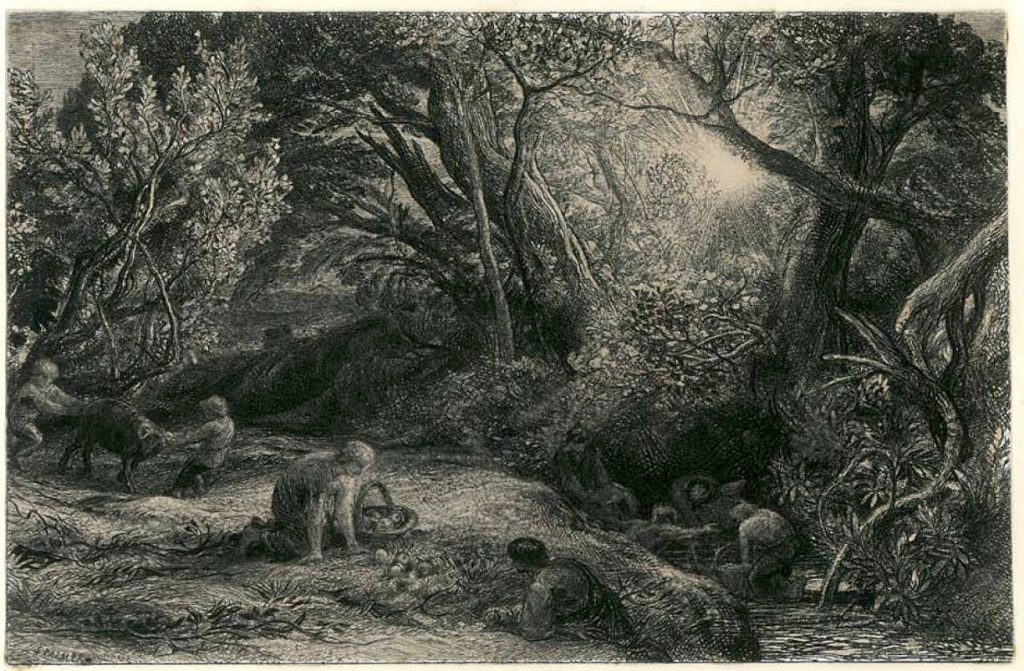

Samuel Palmer (1805-81), painter and printmaker, is one of Britain’s greatest artists of the Romantic period. He is perhaps best known for his visionary paintings created during the time he lived in Shoreham, Kent, and his close friendship with the artist, printmaker and poet William Blake (1757-1827).

This exhibition of Palmer’s complete etchings shows the playfulness, beauty and complexity of his compositions. Despite creating just thirteen etchings in his lifetime, Palmer’s technical deftness earned him the posthumous reputation as one of Britain’s leading printmakers.

The works on display are taken from the private collection of Edward Twohig. It is a rare opportunity to see all thirteen etchings together, and alongside works by artists who inspired Samuel Palmer, such as George Barrett (1730-84). Works by twentieth-century artists, including Robin Tanner (1904-88) and Paul Drury (1903-87) illustrate the influence Palmer had on the generations that succeeded him.

The first etching recalled the walk we’d just made through the water-meadows.

In Palmer’s etching, a shepherd at his cottage gate stood watching the bird; his dog, too, watched. The trees were heavy with night, the clouds just beginning to part with the coming day… The lark’s song of light outlined the crowded sheepfold and the crisped, bowed heads of a field of wheat which, as always, Palmer could not forget. Larks traditionally sprang from wheat… and fell again, straight as stone, to the deep concealing meadow. They were silent as they fell, Dante wrote, because they were satiated with sweetness. Palmer’s son Alfred observed that at his father’s burial in 1881 a lark sang joyously above them the whole time, ’till, as the last words of the service died away, it dropped silently into the long grass’.

My introduction to Samuel Palmer came via A Vision Recaptured: The complete Etchings and the Paintings for Milton and for Virgil that I got second-hand at Notting Hill Books. It included five facsimile etchings, and as a picture framer I couldn’t just leave them in the book, I had to frame them. I gave away a couple as presents and those I kept have watched over me ever since.

The Rising Moon or An English Pastoral

The paintings of Palmer’s ‘visionary years’… were done under ‘ideal’ conditions in the secluded valley of Shoreham, safe from the hated machines of the encroaching industrial revolution (of which Palmer wanted no part). He was surrounded by friends such as Richmond and Calvert – the ‘Ancients’, as they liked to term themselves, who were all young and idealistic and as yet unencumbered with responsibilities. Here they were visited in a cottage… by their ‘master’, William Blake. Here Palmer was able to give full reign to his imagination and to his ‘poetic genius’, which Blake had taught him must be the inspiration of all ‘true Art’.

How different was Palmer’s ‘sanctum sanctorum’, the etching corner at Furze Hill, where he settled almost thirty years later… His son, A H Palmer… has given us a description of his ‘retreat’ at Furze Hill:

“Samuel Palmer’s study at Furze Hill was a small, comfortable room, to which only a chosen and privileged few were admitted… On one side were other and much larger shelves, holding portfolios, in which were classified the innumerable sketches of all sizes… a life’s selection from Nature’s material, landscape and figure… Then came that ‘sanctum sanctorum’, the etching corner – a rough, home-made cupboard, standing on a chest of drawers; containing, the one a veteran set of tools and a stock of copper plates, new or in progress; the other… some favourite etchings by other hands, and a few relics of the childhood of the son and daughter who were dead… a room of the smallest pretensions to luxury…”

Palmer was a meticulous craftsman who found the complexities of etching very much to his taste, and he was able, too, in these… to pursue his early preoccupation with the effects of light and shade, particularly in the evening and at dawn. ‘The Lonely Tower’ and ‘The Bellman’…reflect the accumulated visual experience of a lifetime; and they represent a continuity with the style and spirit of his Shoreham work.

A Vision Recaptured – The Etchings and The Designs For Milton and Virgil: Raymond Lister

※

※

Walk the walk: Oil on Canvas at Sudbury Common Lands

As always, beautiful and interesting.

I like the ivy-topped pillbox. It is as if Nature looked at it and said, “You are an ugly and mean thing. You won’t do here. I shall reclaim this space, despite you.” It brings to mind Tyler Durden’s vision of thick kudzu vines growing up abandoned skyscrapers in Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club.

Thanks Bill. I don’t know about Fight Club but I do know it’s always good to see Nature getting its own back.