The Anni Albers exhibition at Tate Modern begins with a handloom. It is a wooden instrument made of frames and strings and pedals, with a stool for its operator to sit on. Threads pass rhythmically to and fro, writing the score of warp and weft. It might be likened to a piano whose musical offerings are captured for posterity in recordings of woven textiles.

Entering the exhibition we were watched by weavers at the Bauhaus workshop in 1928.

Anni Albers is in the bottom row, second from left.

The Bauhaus art school in Weimar was founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius, who wanted to create a school that brought together sculpture, painting, arts and crafts… Weaving was a popular class for women, and – despite the ideals of equality at the Bauhaus – it soon became known as the ‘Women’s Workshop’. Anni Albers said that she ‘went into weaving unenthusiastically, as merely the least objectionable choice’, but ‘gradually threads caught my imagination’.

Students in the weaving workshop produced independent artistic works as well as designs for industrial manufacture. Albers and her colleagues created wall hangings, which she later referred to as ‘amazing objects, striking in their newness of conception in regard to use of colour and compositional elements’. The weaving workshop developed its own distinctive language, making use of the grid structure of weaving, and emphasising haptic or tactile qualities. A number of lost wall hangings by Albers were later re-woven by Gunta Stölzl who was Master of Craft in the weaving workshop from 1927 to 1932.

Design for a wallhanging, 1926

The notations on these drawings were used by Anni Albers to calculate the number and colours of warp threads they would need to set up the loom. These methodical and grid-like designs were painted in watercolours in four or more different tones and were exercises in colour theory. When produced as large-scale weavings, only three colours of thread would be used: red, white and black. The mid-pink and grey colours would be made using a red weft on a white warp.

Preliminary design for a wallhanging, 1926

These designs of horizontals and verticals seem to echo the construction of the loom itself.

Design for a wallhanging, 1926

In 1933 the Nazis forced the Bauhaus school to close. Josef and Anni Albers were offered teaching positions at the newly founded, progressive art school Black Mountain College in North Carolina, US, following a recommendation from the architect Philip Johnson. Set in a rural environment, Black Mountain College encouraged experimental teaching methods and communal living. Artists, dancers, mathematicians, sociologists and architects formed an unusual creative and intellectual community.

Untitled, 1941

Untitled, 2018

The framed weaving on the wall reflected by a metal grid on the floor.

Red Meander, 1954

This piece, and the one below, bring to mind the abstract designs of Shoowa and Kuba textiles and the quadrangular Kufic inscriptions of texts from the Qur’an. And also the maze at Warren Street station.

Two, 1952

AA made a number of works that reveal her interest in the relationship between text and textile.

Development in Rose I, 1952

“To let threads be articulate again and find a form for themselves

to no other end than their own orchestration, not to be sat on, walked on,

only to be looked at, is the raison d’être of my pictorial weavings.”

Development in Rose II, 1952

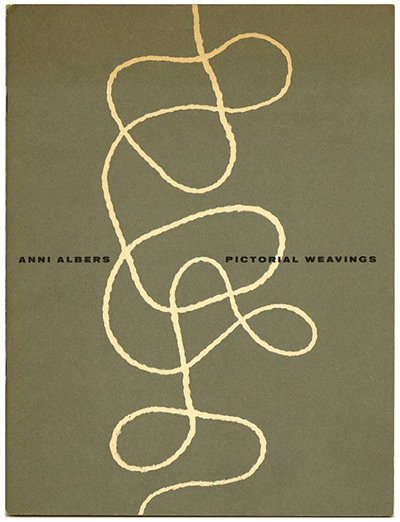

Anni Albers distinguished between the textiles she designed for architecture or interiors, and her smaller ‘pictorial weavings’. These works explore what Albers described as ‘a form of weaving that is pictorial in character, in contrast to pattern weaving, which deals with repeats of contrasting areas’. In essence, they are artworks that have been made with the materials and processes of weaving.

Albers made many of her pictorial weavings in the 1950s in her house in New Haven, Connecticut. She used a small handloom to create these pieces, several of which incorporate a technique known as leno or gauze weave, where the vertical warp threads twist over each other around the horizontal weft threads. Some works, such as ‘Development in Rose I’ and II, both 1952, may have been made on the same continuous warp threads, as companion pieces. But since they have been exposed to different conditions, the coloured threads have faded differently over time.

Pasture, 1958

Generally smaller scale than the wallhangings, these (pictorial weavings) are exercises in combining traditional with innovative techniques, pushing the weaving process in new directions… using leno weaves that group the threads together in little bundles and take structure to its very limit, as if the grid were activated with an almost frenetic agitation. This has the effect of making the vertical and horizontal accents almost seem to collapse in the middle of ‘Pasture’ 1958, for example. These play on gradations of dark through light, as well as on open and closed structures. Each section of the whole is different, even if the patterns loosely repeat. Bright red overstitching provides highlight and accent. These pictorial weavings seem so much about process that they may appear to be far removed from Albers’s earlier interests in painting, yet it is not hard to see how the intricacies of threading still relate to (Paul) Klee’s own delicate graphism of scratched crosses and lines. Arguably Klee’s legacy is most clearly felt in Albers’s work, even though this could only have been woven.

Close to the Stuff the World is Made of: Weaving as a Modern Project – Briony Fer

Red and Blue Layers, 1954

If Paul Klee took a line for a walk then Anni Albers led her threads on a beautifully choreographed dance, full of wild, spectacular, unexpected moves. These lines went walkabout with a New Orleans marching band, joined a circus, sang in a choir, danced in a Broadway boogie-woogie chorus line.

Thickly Settled, 1957

South of the Border, 1958

Dotted, 1959

Study for Six Prayers II, 1965-6

Six Prayers, 1966-7

Though born to a Jewish family, Anni Albers was baptised in a Protestant church and referred to herself as ‘not Jewish’, except, ‘in the Hitler sense’… In 1966-7 Albers made her most ambitious pictorial weaving, ‘Six Prayers’. She was invited by the Jewish Museum, New York, to produce a tapestry memorialising the six million Jews who died in the Holocaust… In a review, ‘New York’ magazine critic Mark Stevens described the work as, ‘an important piece about the Holocaust that has the dignified presence of religious ritual. The six weavings resemble prayer shawls. The interlacing of discordant lines suggests both control and mayhem, darkness and light; human beings appear woven of good and evil on the loom of nature’.

Temple Commissions and Six Prayers – Ann Coxon

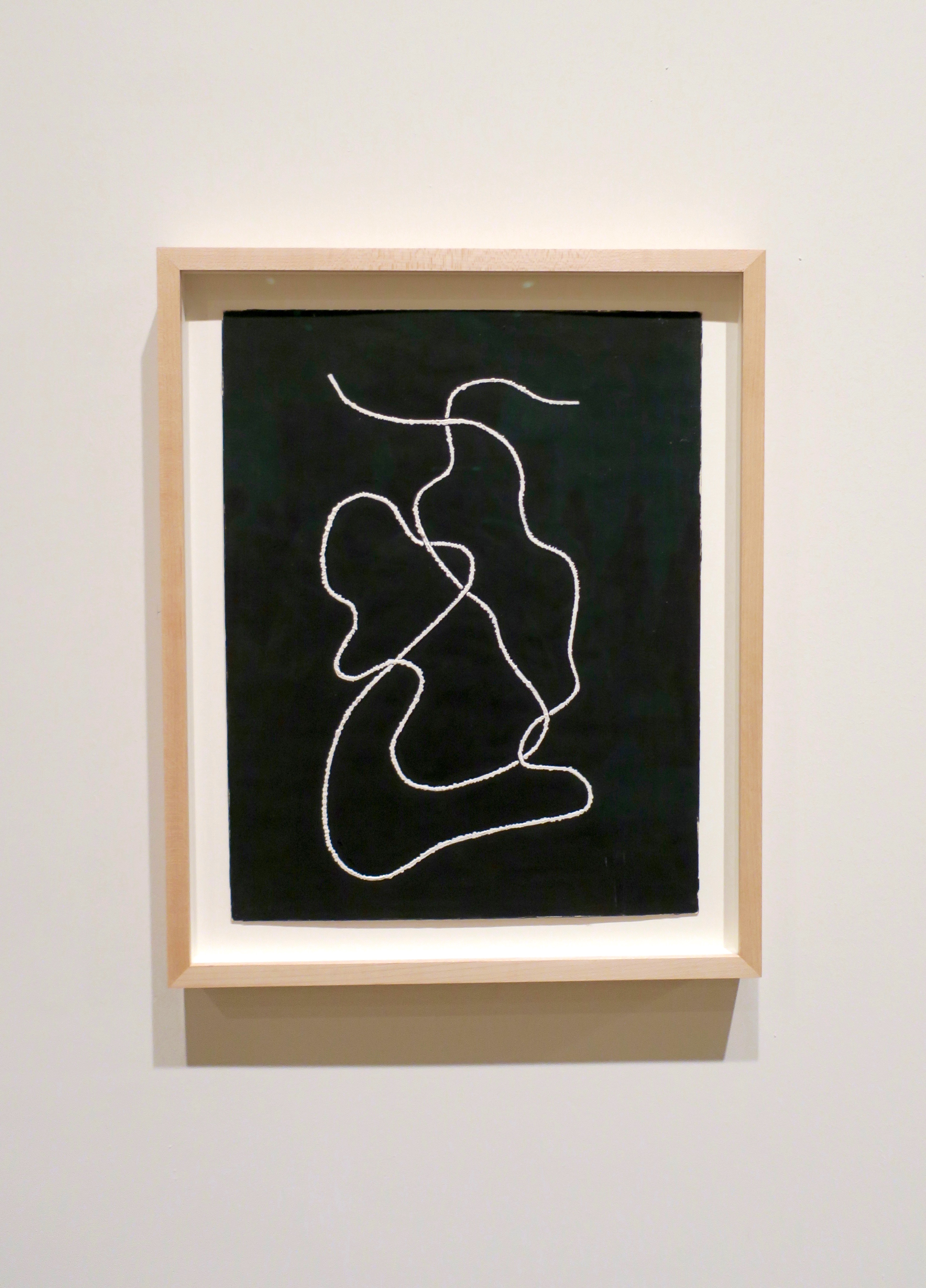

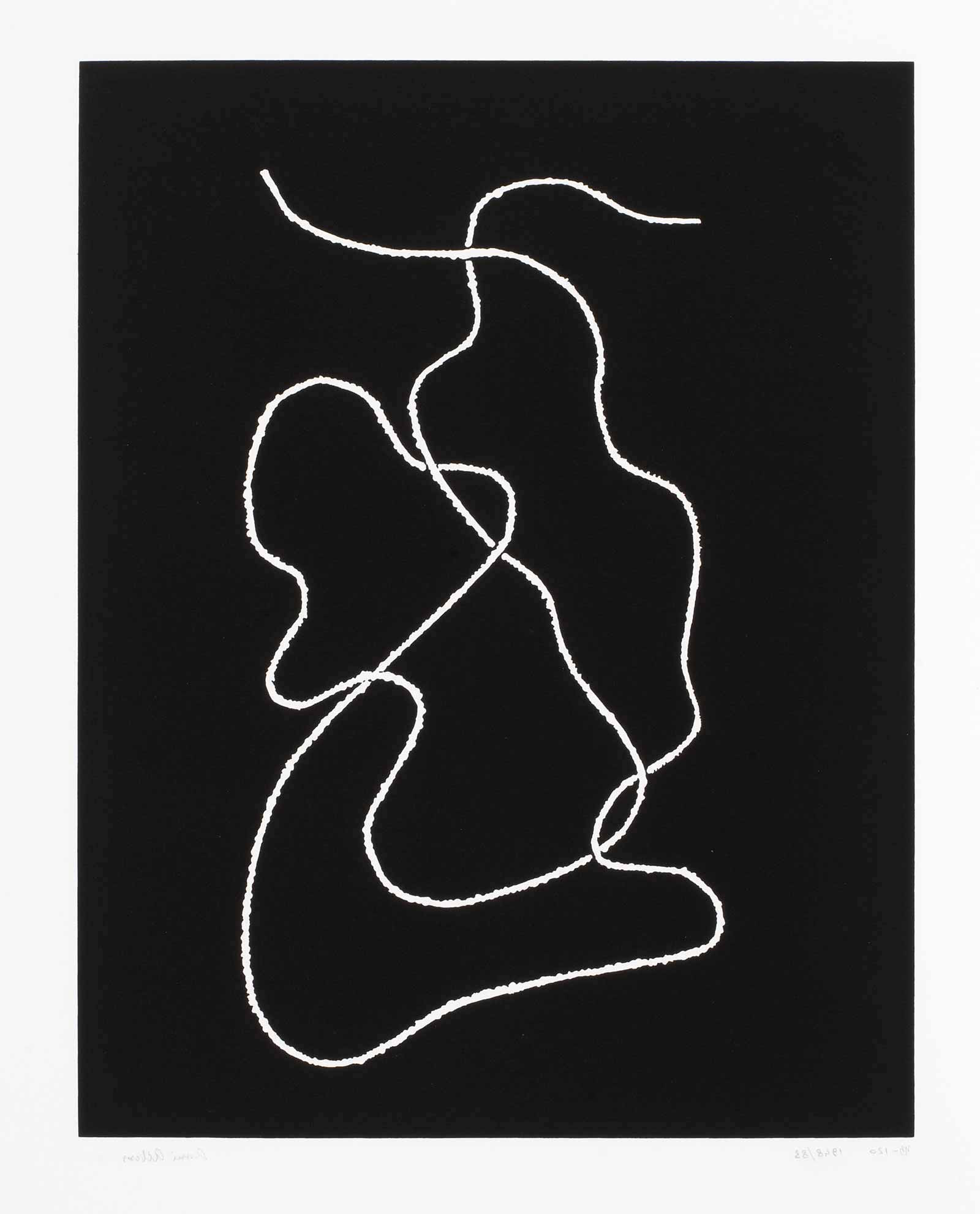

Drawing for a knot, 1948

The word ‘knot’ has many meanings. In hand-weaving it can signify a tangled mass, but also a patterned fastening or interlacing of threads. In mathematics a knot is a tangled loop in three-dimensional space. Knots entered Anni Albers’s work in 1947. Surprisingly they made their appearance in the form of calculated, deliberate, delicate tangles in gouache on paper, carefully signed, titled and dated. This was surprising, because Albers made few paintings outside her woven or graphic work, and rarely did she sign, title or date them. The 1947 ‘Knot’ paintings are surprising, too, in their lightness of hand and sureness of form. They point to careful consideration, yet they appear quite spontaneously as if, after more than two decades of learning to understand the material qualities of threads, she was bent on scrutinising their intrinsic behaviour.

Tangles, Knots, Braids, Loops and Links – Brenda Danilowitz

Knot drawing, undated

Drawing for a knot, 1947

Knot 3, 1947

Knot, 1947

This is not an Anni Albers, but all these knot drawings remind me of one of my drawings, made a few years ago as a design for my daughter’s wedding invitation. I like to think Anni would have approved.

True Lover’s Knot, 2002

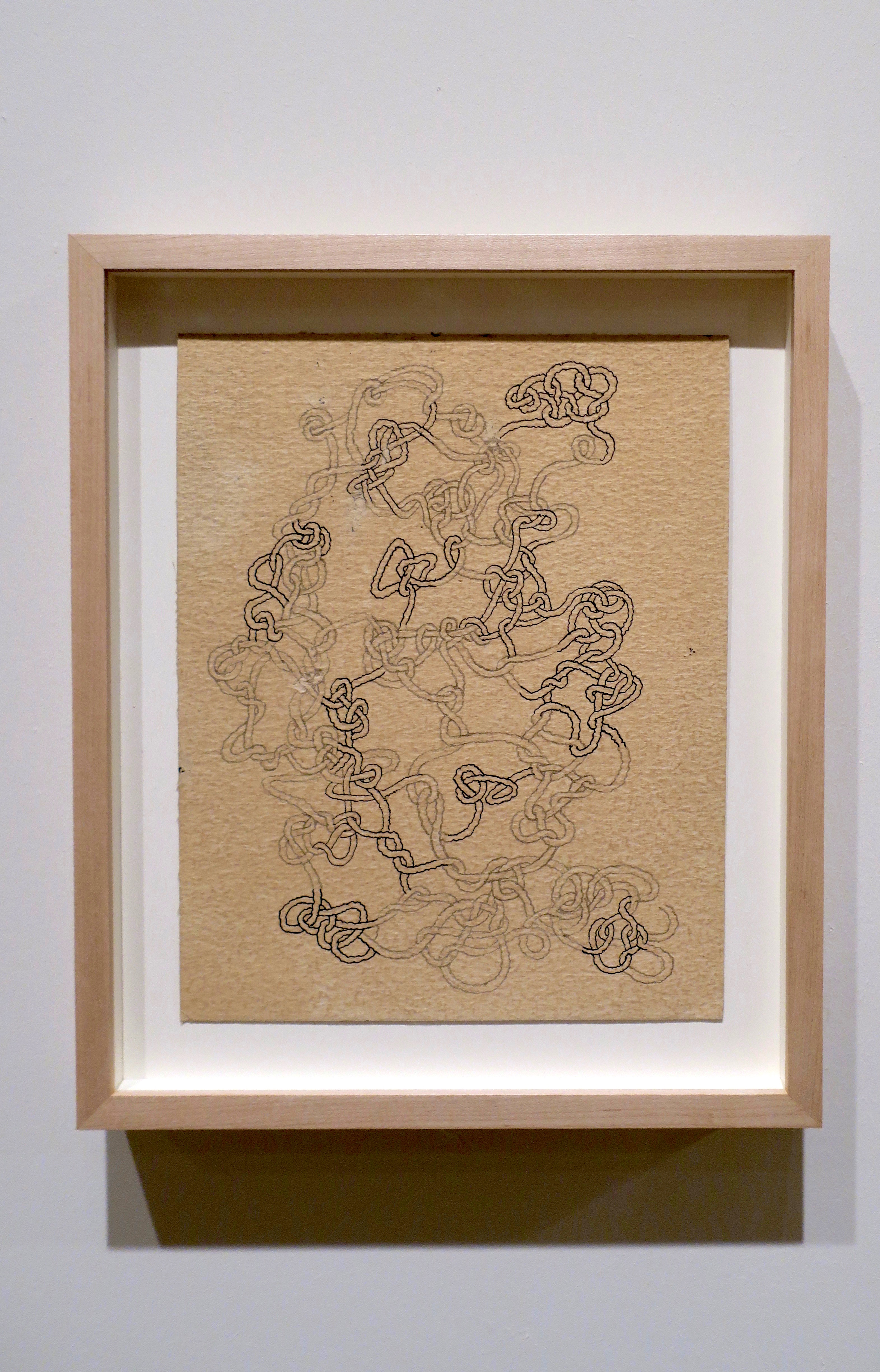

Drawing for a Rug II, 1959

Study for a Nylon Rug, 1959

Rug, 1959

A great tangled design carefully woven from untangled threads.

This is a memory generator, a picture of a brain that brings me back to the street where I was a six year-old, scratching drawings of roads on the pavement to drive my toy cars around, then later, with the advent of electricity, it’s what my Scalextric aspired to, on a soft rug and no more grazed knees.

Sampler, Peru, Chimú, 1100-1300

This unravelling weaving is from the Josef and Anni Albers Collection of pre-Columbian artefacts. It makes me think of puppets on strings. There are many more examples on show. It’s an exhibition within an exhibition with pieces from Mexico, Bolivia, Chile and Peru and a lovely Shoowa textile from the Congo. There are letters from friends, books by contemporaries and weavings by students.

Lekythos: Leonore Tawney, 1962

Black White Yellow, 1926

The exhibition takes us from the blocky, stripy weavings of the Bauhaus, their designs plotted according to warp and weft, to the cursive, tangled later weavings that go against the grain of the loom. It’s like watching the paintings of Sean Scully metamorphose into those of Brice Marden.

Under Way, 1963

Intersecting, 1962

※

※

When Anni Albers left Germany for the United States in 1933, she brought her 6 x 7 ft. countermarch Flensburg loom with her. The loom has been refurbished and is in the collection of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. In this short film by Alberto Amoretti and Giovanni Hänninen, weaver Addison Walz demonstrates the loom in action.

※

If you enjoyed this post you might also like to see – Entangled: Threads & Making.

I feel like I’ve just been round the exhibition again reading this. Excellently comprehensive and love the close up photos of the leno/gauze weaving particularly. Best review so far! It is such a brilliant exhibition.

Thanks Julia, you are too kind! A review maybe in the déjà vu sense. It is indeed a brilliant exhibition and there’s so much more to it. That room of ‘pictorial weavings’ was worth the price of admission alone. I’m glad you enjoyed it too.