Raven Row is a new gallery in Spitalfields. It is presently home to a wonderful exhibition of textile fragments, courtesy of the Centre for Social Research on Old Textiles. With little prior knowledge of the subject the beauty of the undertaking for me was initially its presentation and framing, which is just breathtaking. This is a beautifully renovated building and the exhibits are respectfully displayed. The delicate hand-wrought artefacts in their vitrines and the elegantly proportioned rooms combine to make this a place of pilgrimage.

The exhibition reflects, among other things, on the geographic and historic context of its setting. Situated in the former silk-weaving district of Spitalfields, Raven Row is housed in buildings on Artillery Lane, which in 1754 were converted by two Huguenot silk merchants into shops when the street’s name was Raven Row. In 1766 an import ban on foreign woven silk helped develop a lucrative textile industry in Spitalfields. The end of this embargo in 1824, together with other factors, led to its collapse, leaving the area to fall into poverty until its proximity to the burgeoning financial sevices district allowed it to prosper again.

The pieces on show are from the CSROT Historic Textile Collection assembled by Seth Siegelaub over the past thirty years. There are woven and printed textiles, embroideries and costume, from fifth-century Coptic to Pre-Columbian Peruvian textiles, late medieval Asian and Islamic textiles, and Renaissance to eighteenth-century European silks and velvets.

Seth Siegelaub was born in the Bronx in 1941. After running his own gallery in New York from 1964 to 1966, he played a pivotal role in the emergence of what became known as Conceptual Art, which resulted in a series of 21 art exhibitions in groundbreaking formats between 1968 and 1971. In 1972 he left the art world and moved to Paris, where he published and collected leftist books on communication and culture and founded the International Mass Media Research Center.

In the early eighties he began collecting textiles and books about textiles, and in 1986 founded the Center for Social Research on Old Textiles, which conducts research on the social history of hand-woven textiles. In 1997 he edited and published the Bibliographica Textilia Historiae, the first general bibliography on the history of textiles, which has since grown online to over 9,000 entries.

As well as textiles there is also a section of the ground floor gallery devoted to a fantastic display of wonderful hats and headdresses. They are a catalogue of all manner of ways of making by hand, ranging through woven, embroidered, knitted, feathered, plaited, beaded, carved and painted.

So far we have seen the modern extension at the rear of Raven Row. Back in the original building the display is as much about the restored fabric of the architecture as it is about the precious artefacts it houses. The various rooms can be seen as frames for these richly worked textiles.

Books on the history of textiles and trade and collecting are also displayed alongside samples of silk brocade and fragments of ecclesiastical and liturgical vestments.

In this room were Coptic tapestry panels from 5th and 6th century Egypt, Nazca textile fragments from 11th century Peru, an Islamic textile fragment from 12th century Egypt, a fragment of embroidered silk from 17th century Assisi and this little red feathered cap whose provenance I’ve forgotten, possibly from Peru, possibly 1000 years old.

The last two rooms on the second floor were dominated by a large painted panel and a headdress-mask from Papua New Guinea. But they were just the prelude to the wall beyond, which was filled with a collection of Mbuti barkcloth paintings. Here was what all the rest had been leading to. They were the culmination of the exhibition for me. This was the stuff that matters. I audibly gasped in amazement when I saw them, much to the amusement of the young female invigilator in the corner of the room. I just wasn’t expecting to find these here. They were a great surprise.

These are painted barkcloth panels made by the Mbuti people from the Ituri forest in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and they have such resonance for me that I feel they deserve a post all to themselves. This is a subject I will return to. They are a fitting conclusion to a wonderful exhibition, where the building and its contents combine as a work of art together. This was the perfect place for it with so many resonances of the silk trade hereabouts. (I was told by the attendant at the desk that Resonance FM were also recently in residence. Another resonance.)

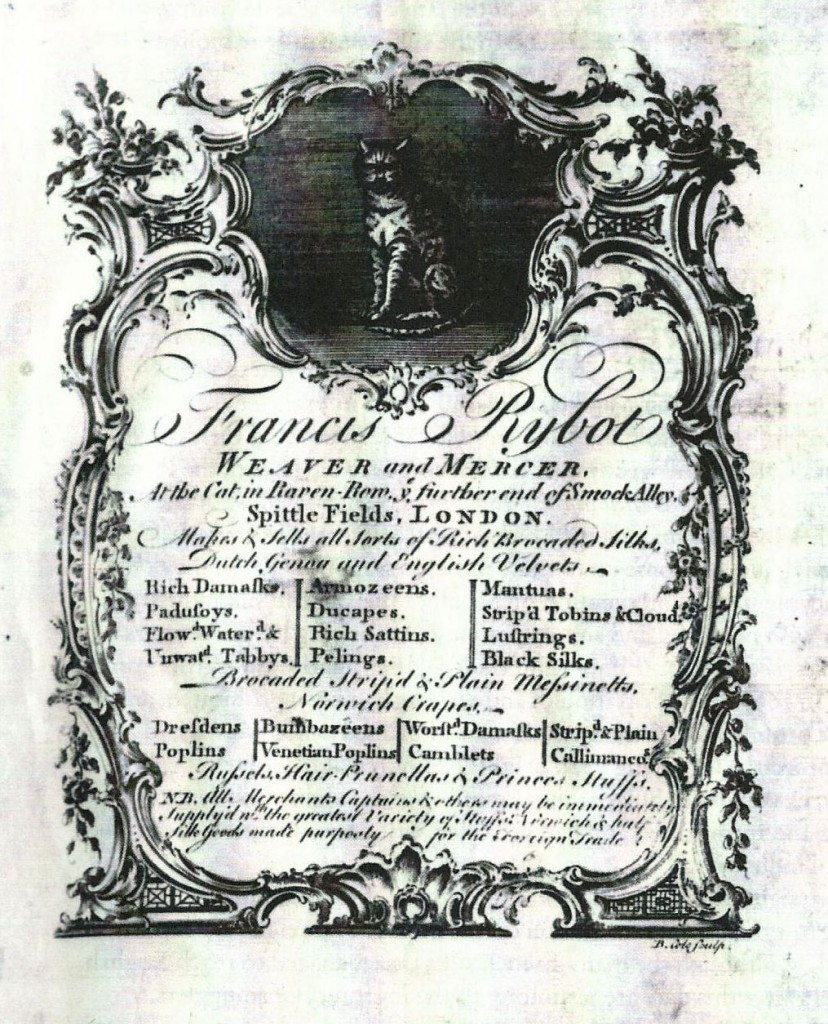

A final coda was this trade card of Francis Rybot, one of the two Huguenot mercers and weavers who occupied Raven Row in the 18th century. At the sign of the cat, a tabby cat, from the French tabis, “striped silk taffeta”, a rich watered silk, from Middle French atabis (14c.), from Arabic attabiya, from Attabiy, a neighbourhood of Baghdad where such cloth was first made, named for Prince Attab of the Umayyad dynasty. Ours is called Cosmo.

Raven Row / The Stuff That Matters

One thought on “The Stuff That Matters”