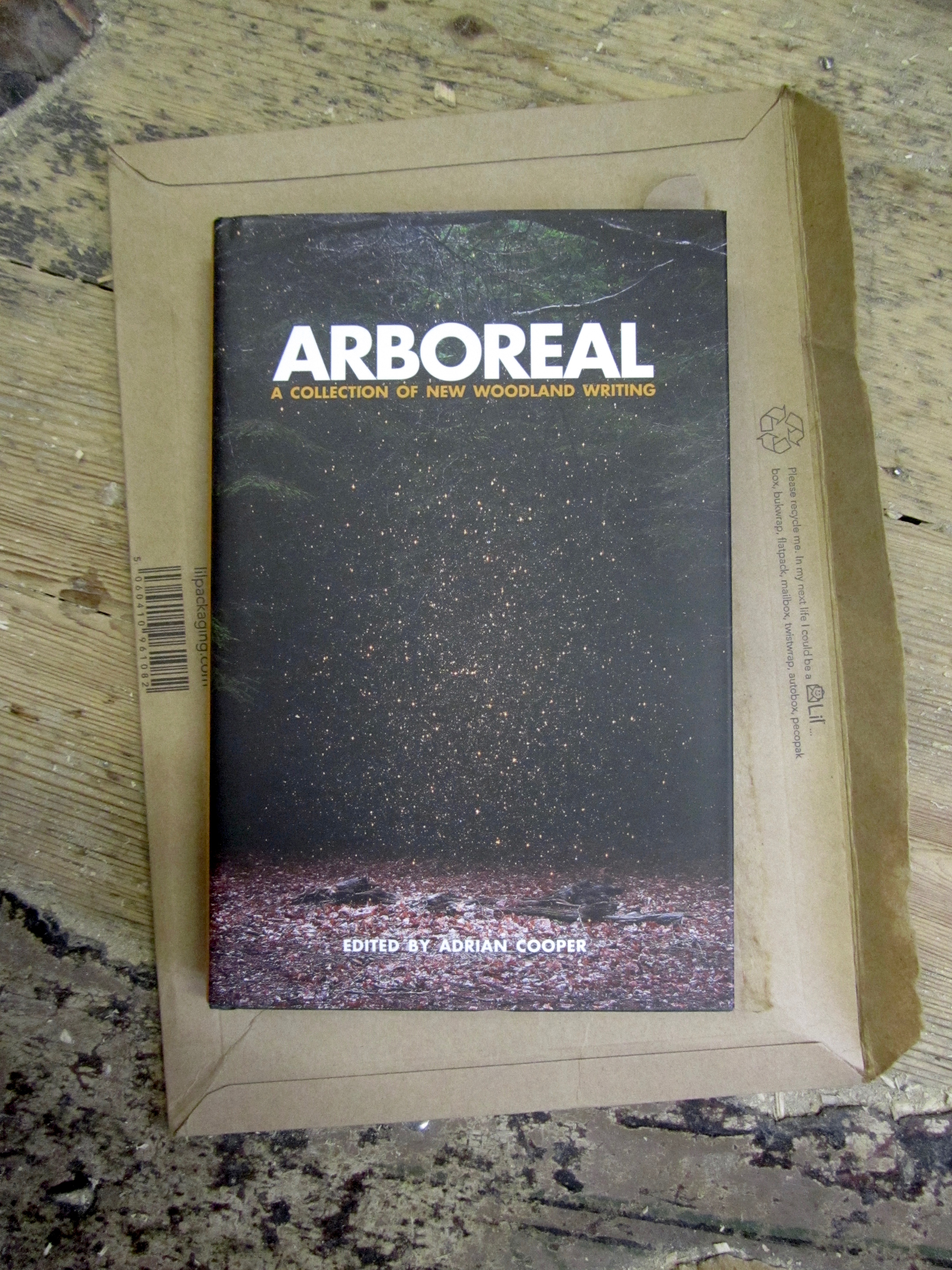

I was reading Up The Forest! one of the many contributions to Arboreal, a book I got late last year. It’s a wonderful compendium of woodland writings, a bumper book of tree stories. In this particular story Sue Clifford recalls her Nottingham childhood, Nottingham Forest FC, the coal mines interwoven with houses, fields and woodland, Robin Hood, Sherwood Forest.

Further east, I can take you to Sherwood proper. Its minster in Southwell shows off the High Medieval feeling for the spirit of woodland. Its arches echo its old habitat, recognisable curls of foliage, oak, maple, hawthorn, are carved reverently in stone and the chapter house is full of Green Men; Nikolaus Pevsner, in ‘The Leaves of Southwell’, argues that these ‘assume a new significance as one of the purest symbols surviving in Britain of Western thought, our thought, in its loftiest mood.’

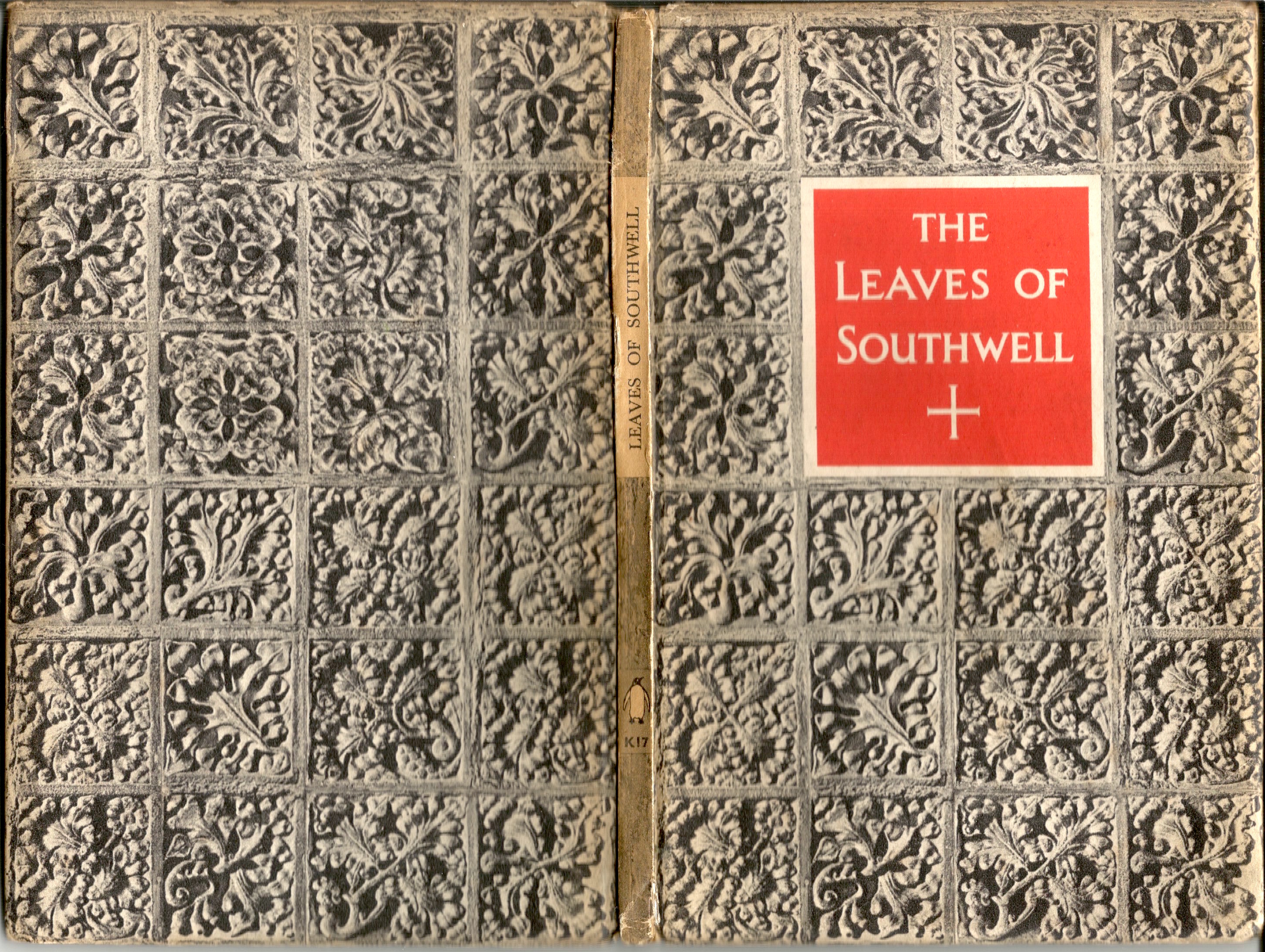

There was something familiar here, The Leaves of Southwell rang a bell. Then I remembered. It was one of the lovely King Penguin books we’d recently received from Julia Hallewell…

Dear Chris, We are clearing out my parents’, Gordon & Evelyn Hallewell’s, home as I am moving since my dad died a couple of years ago. Time to move on. We were all really moved when we found the blogs on your website that referenced the King Penguins my mother asked me to send you when she died, and we’re all short of space for the hundreds of books here so we thought who better to have the other King Penguins than the Rowley Gallery? I hope you enjoy them. Best wishes, Julia.

We’ve now got a fine collection of King Penguins in memory of the Hallewell family. Thank you!

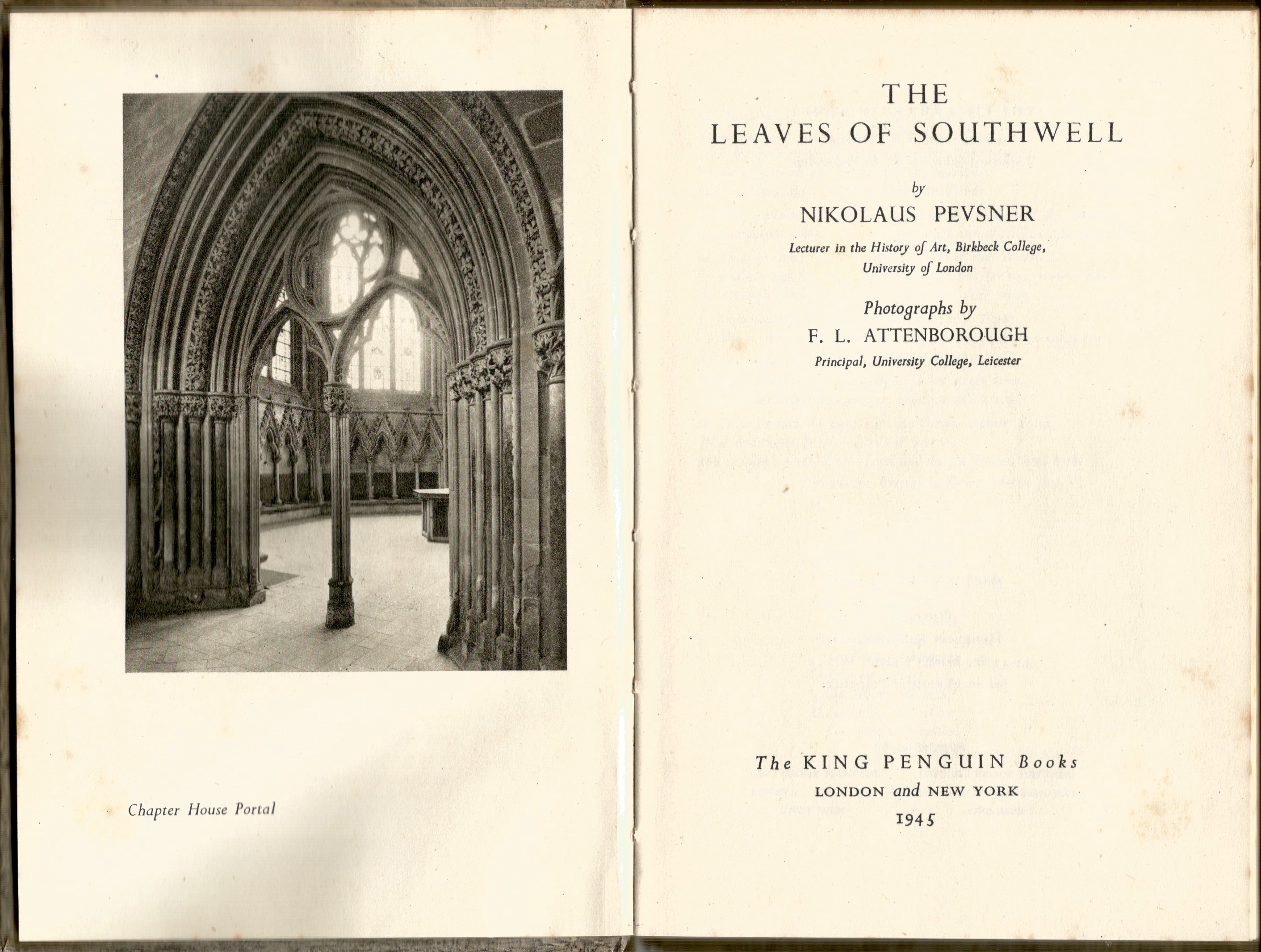

King Penguin Books was a series of pocket-sized monographs published by Penguin Books between 1939 and 1959. They were in imitation of the Insel-Bücherei series published in Germany by Insel Verlag from 1912 onwards, and were pioneer volumes for Penguins in that they were their first volumes with hard covers and their first with colour printing. The books originally combined a classic series of colour plates with an authoritative text… Some of the volumes, such as Nikolaus Pevsner’s ‘The Leaves of Southwell’ (1945)… were pioneering works of scholarship.

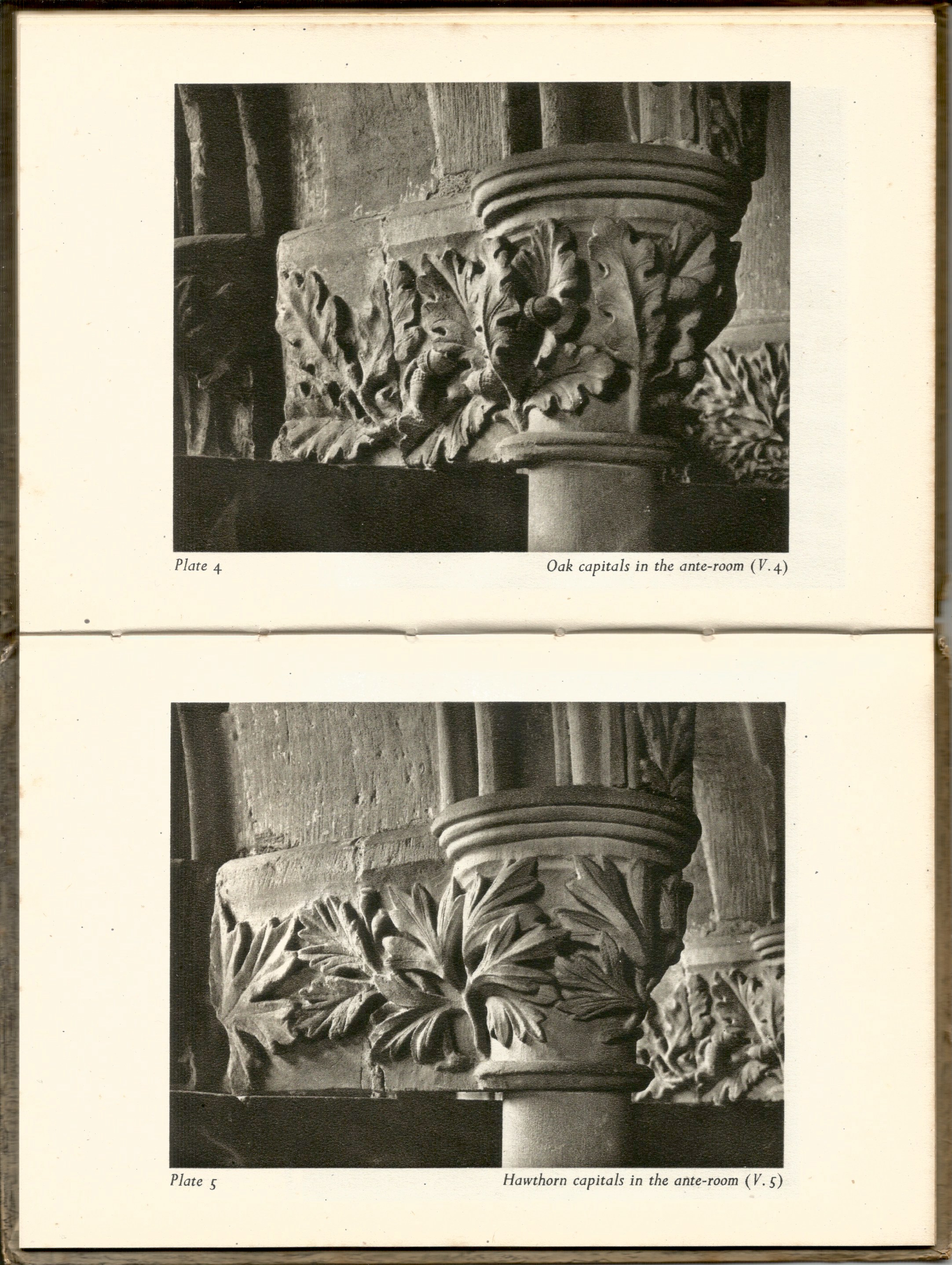

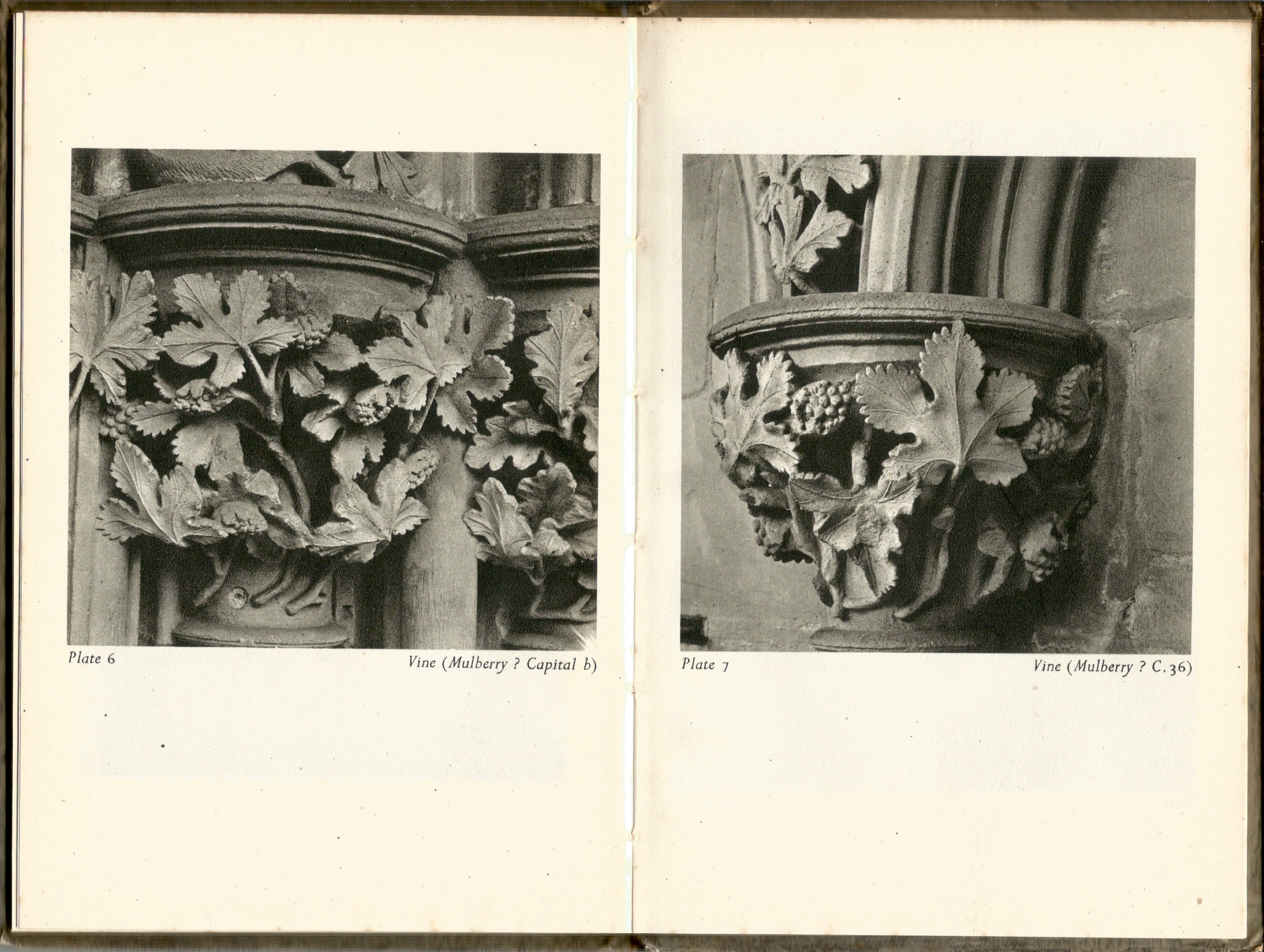

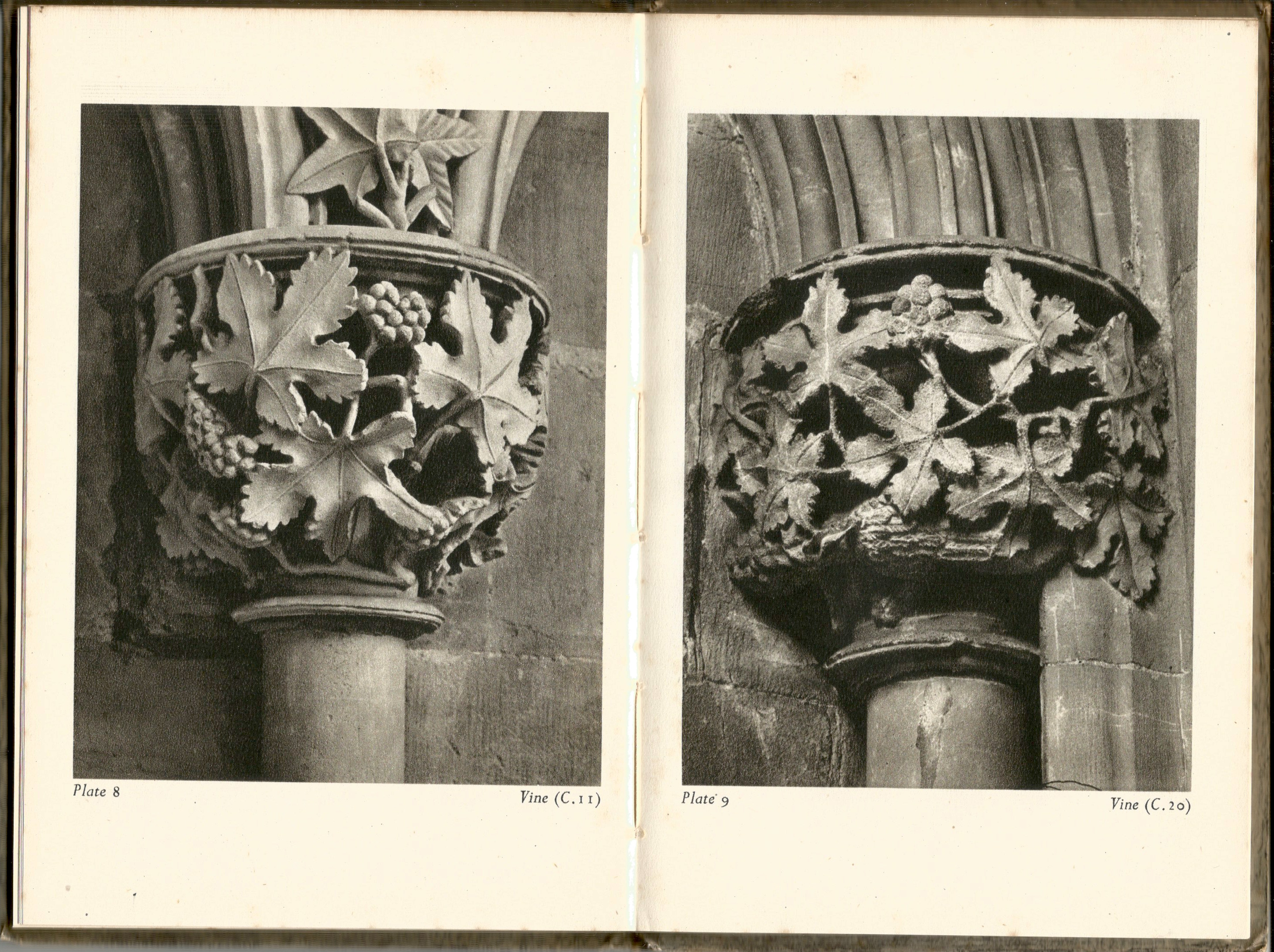

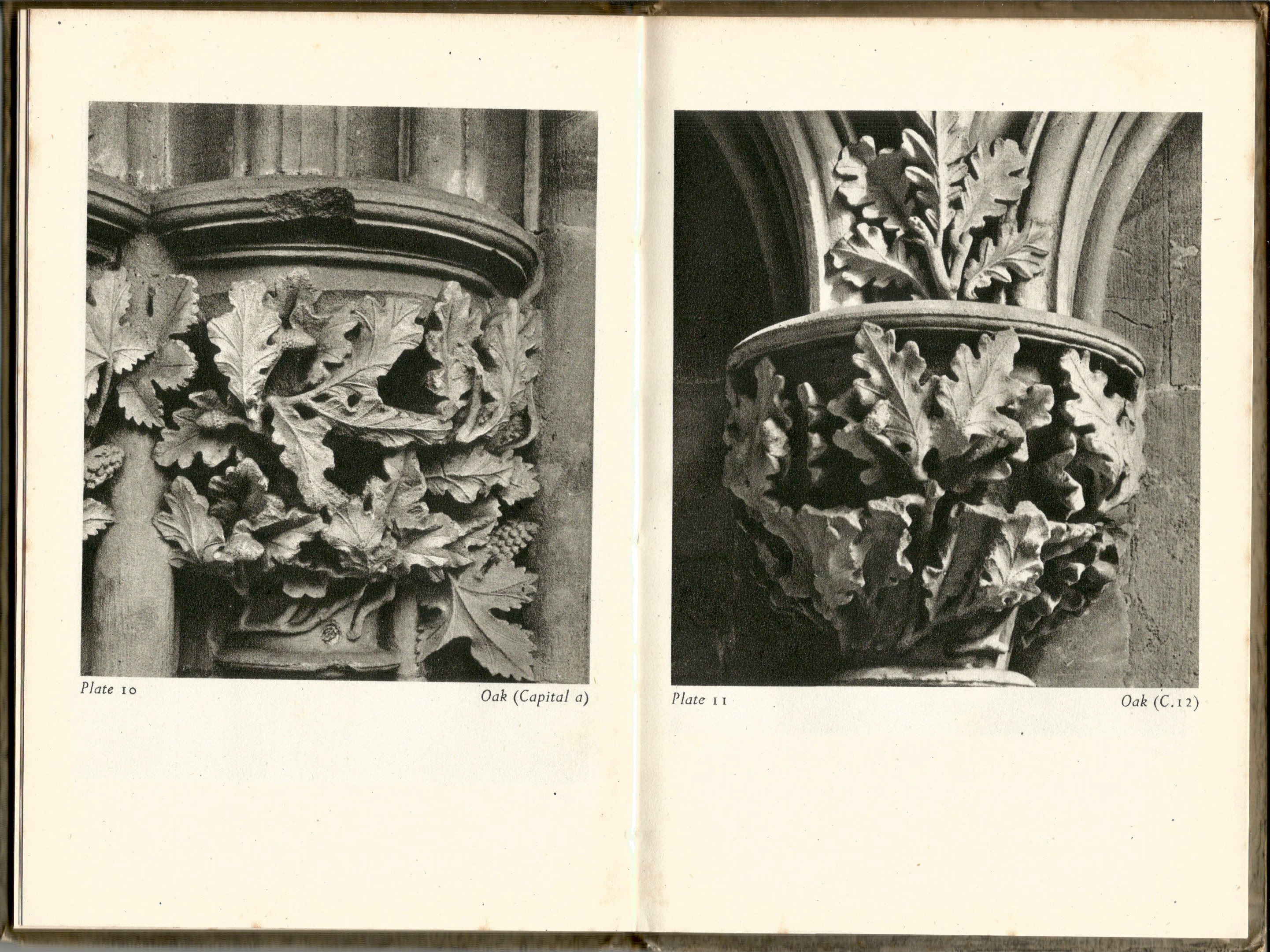

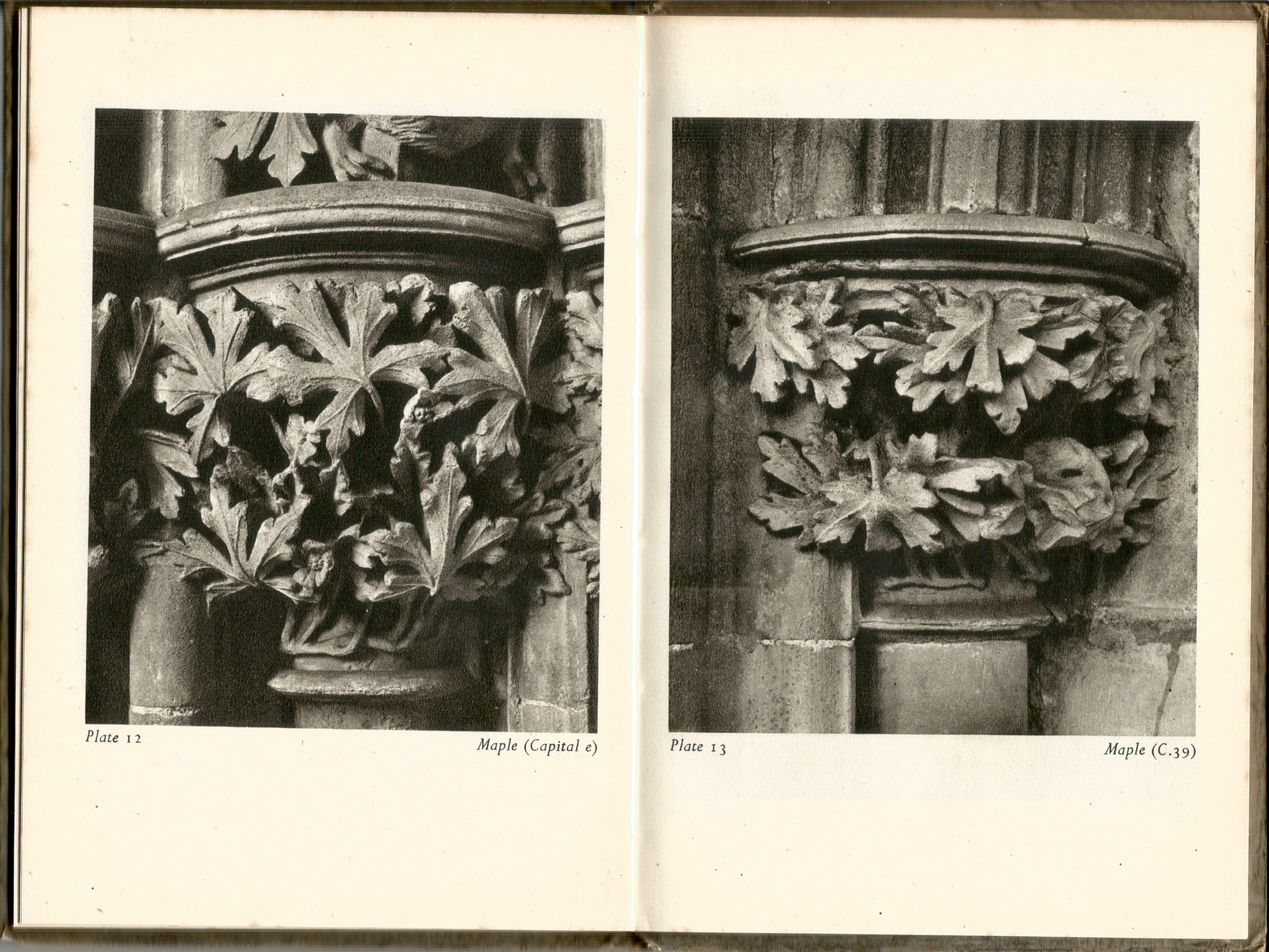

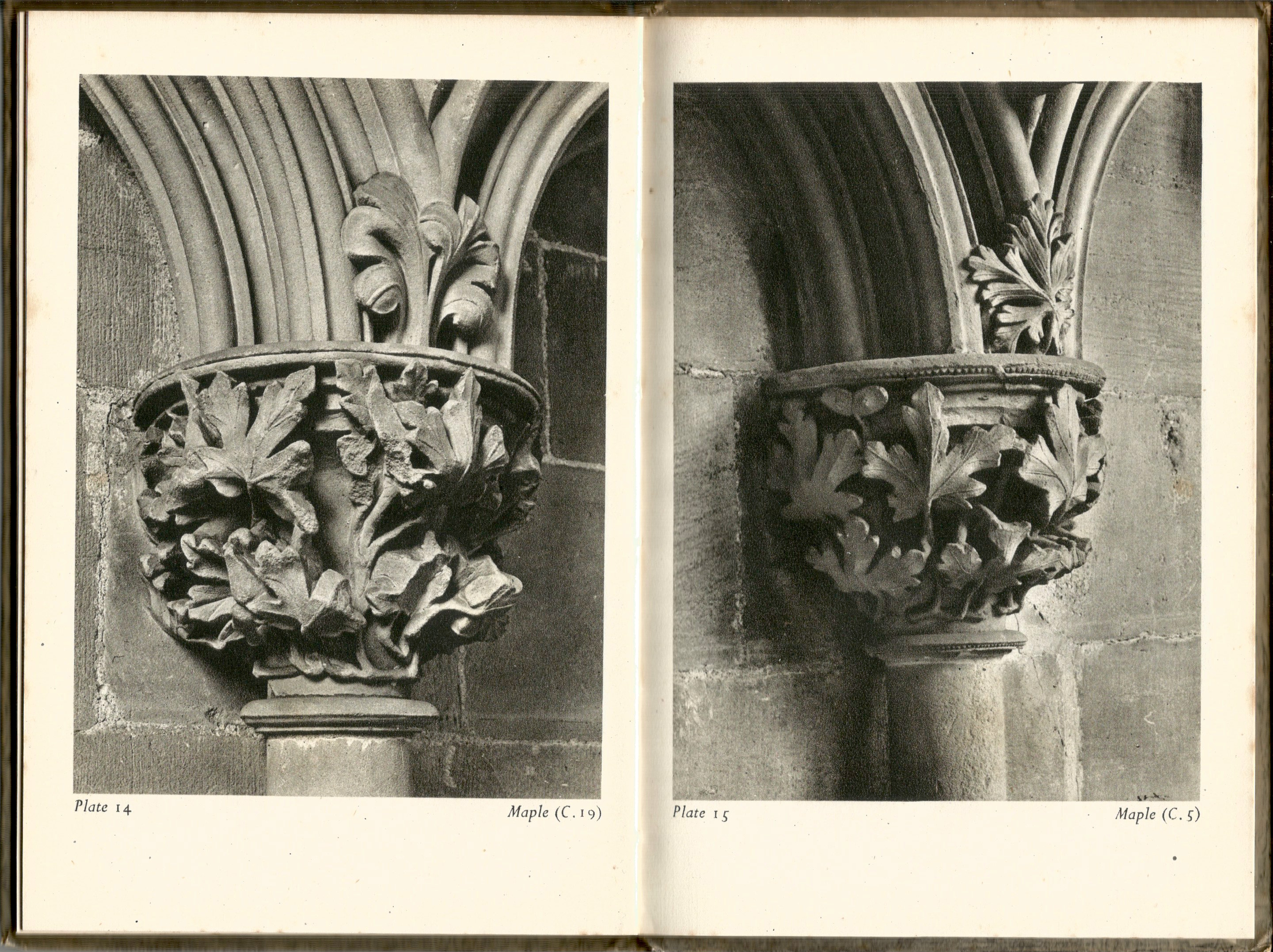

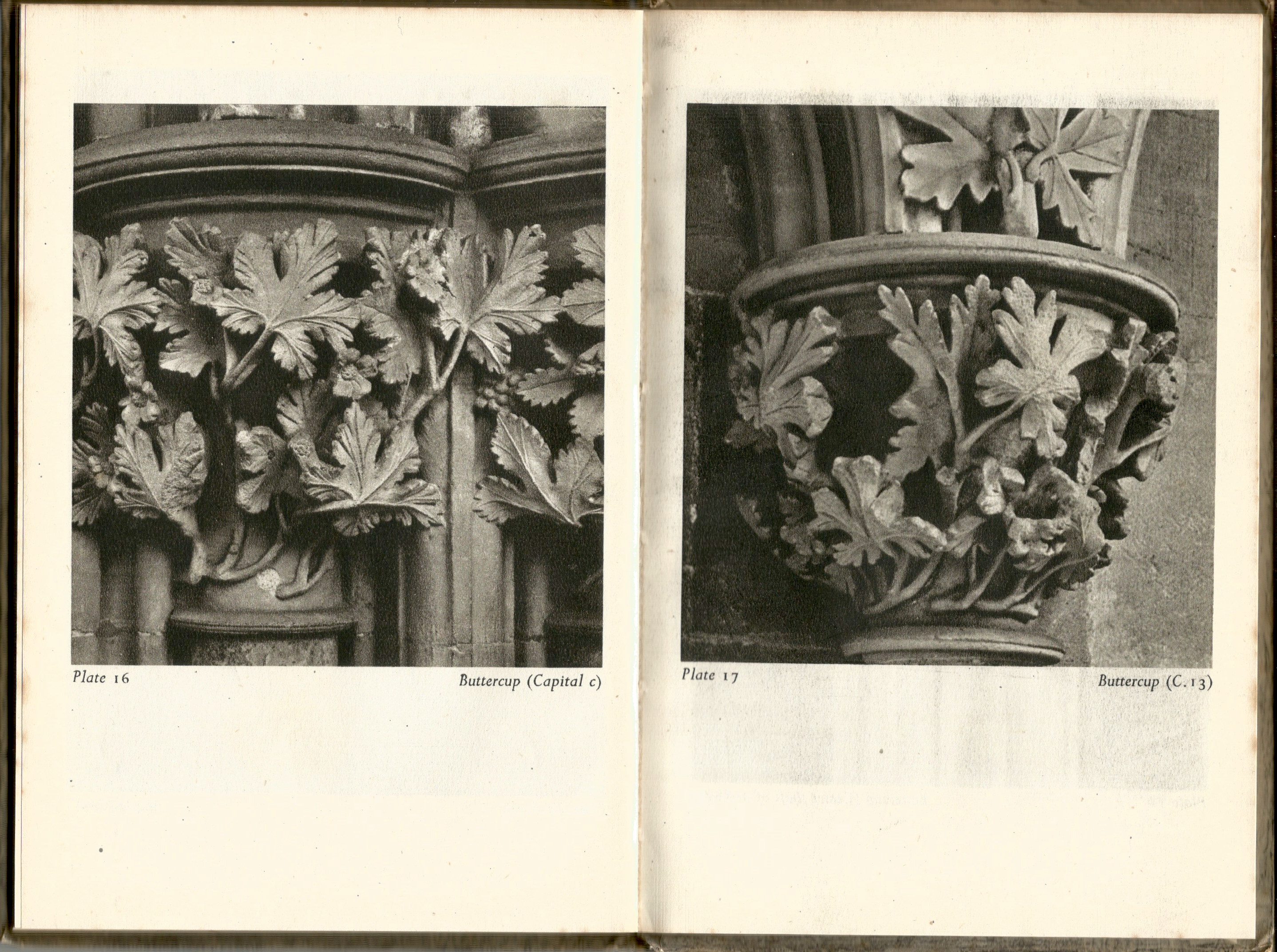

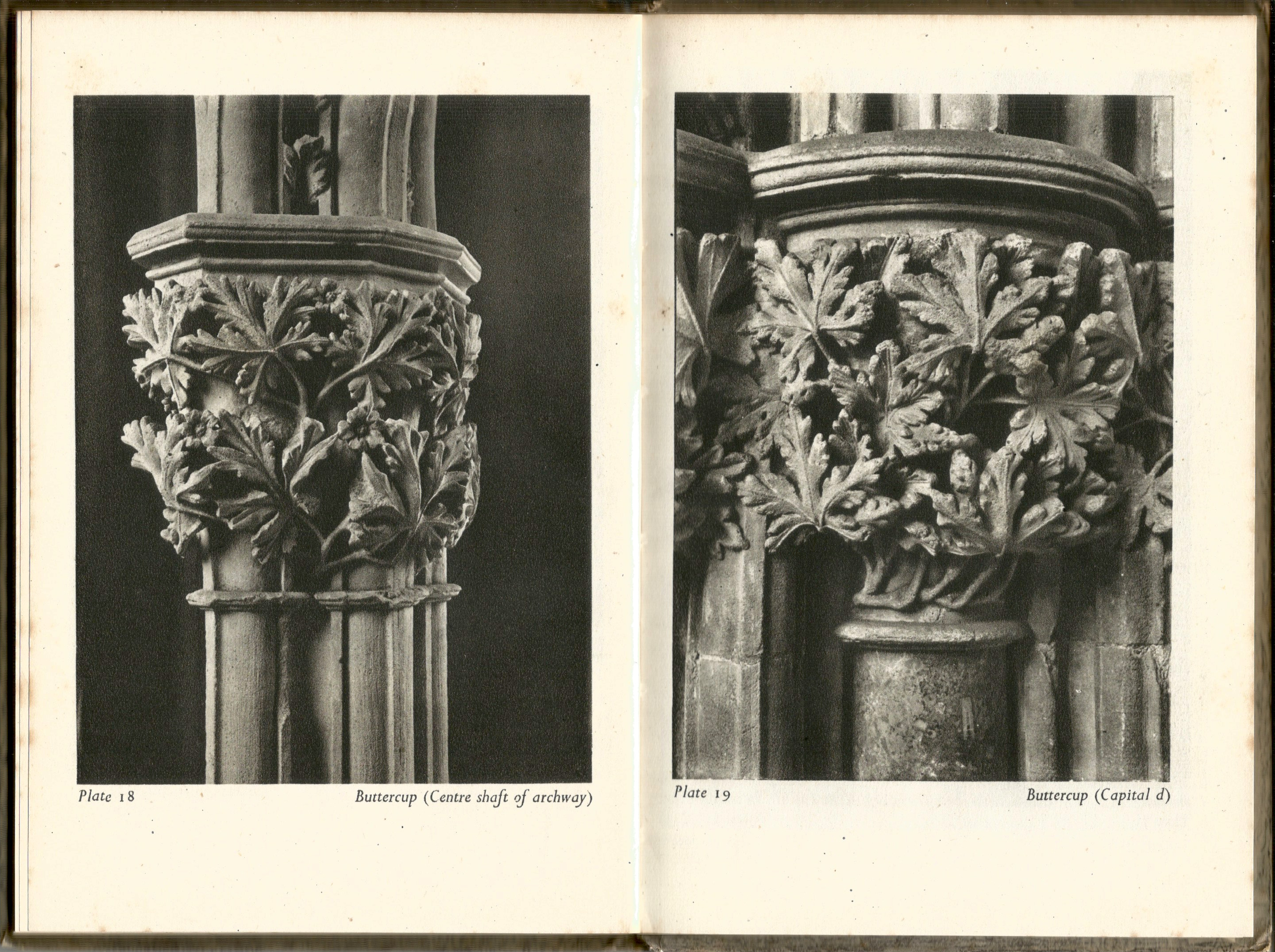

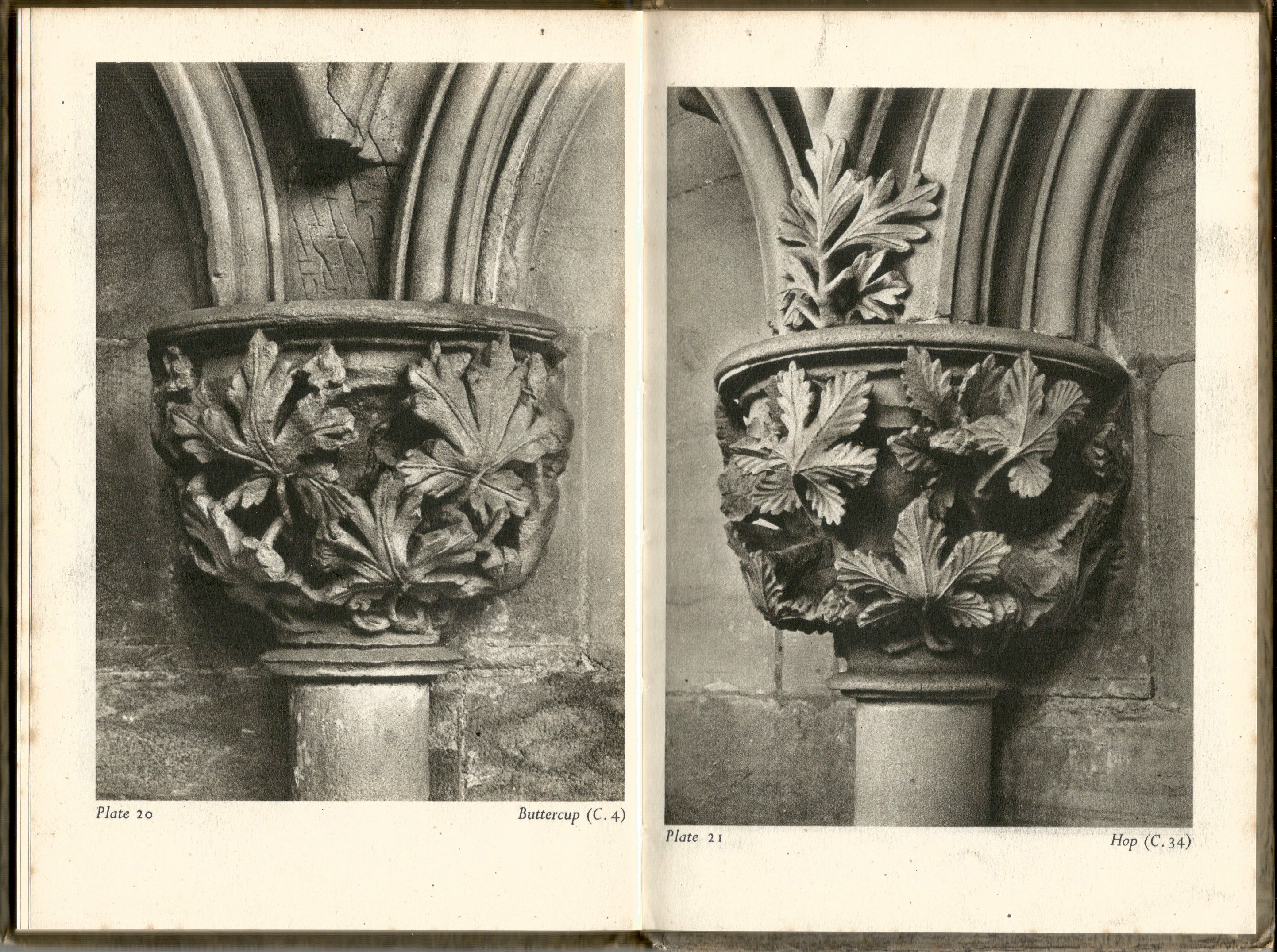

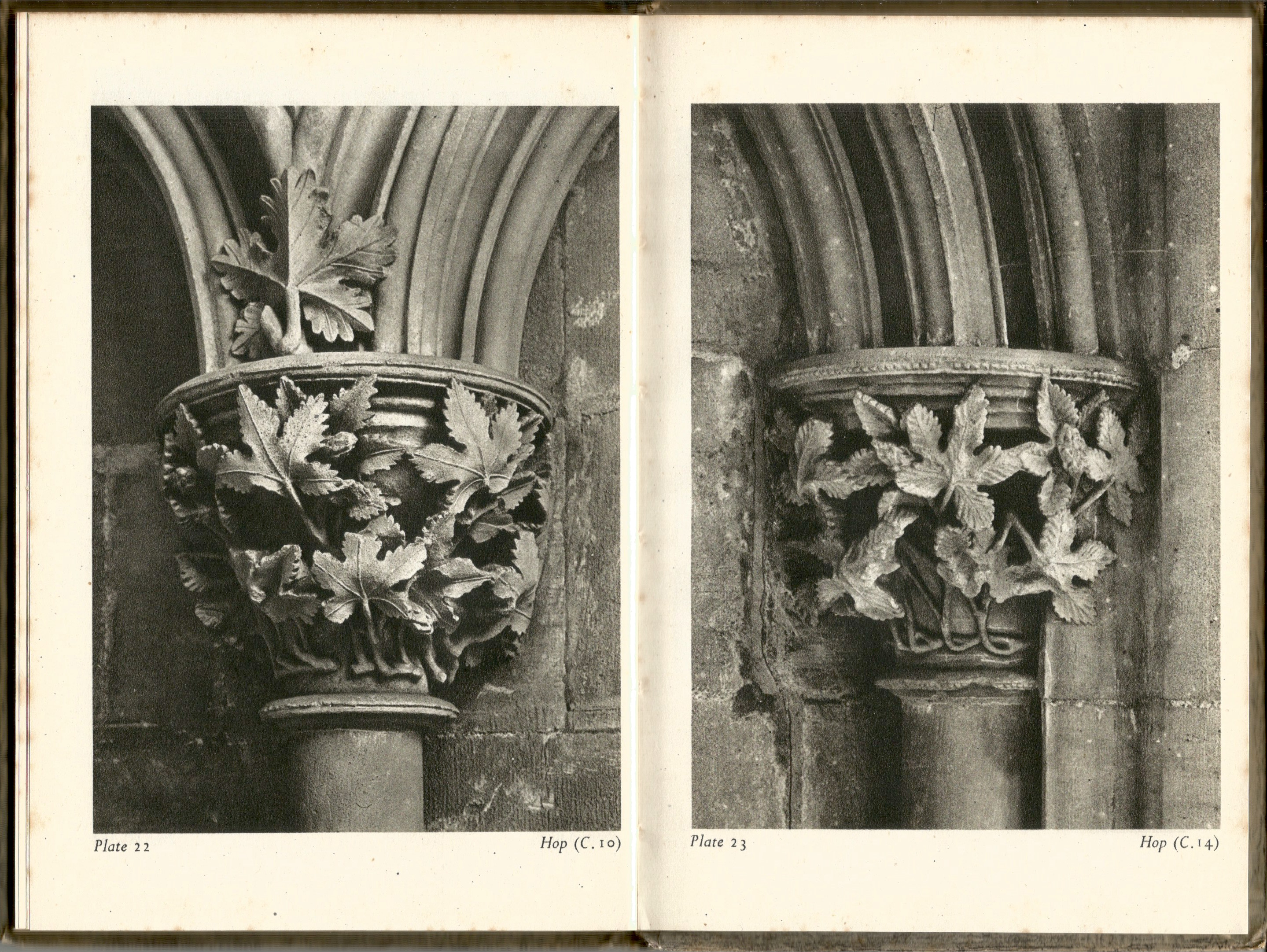

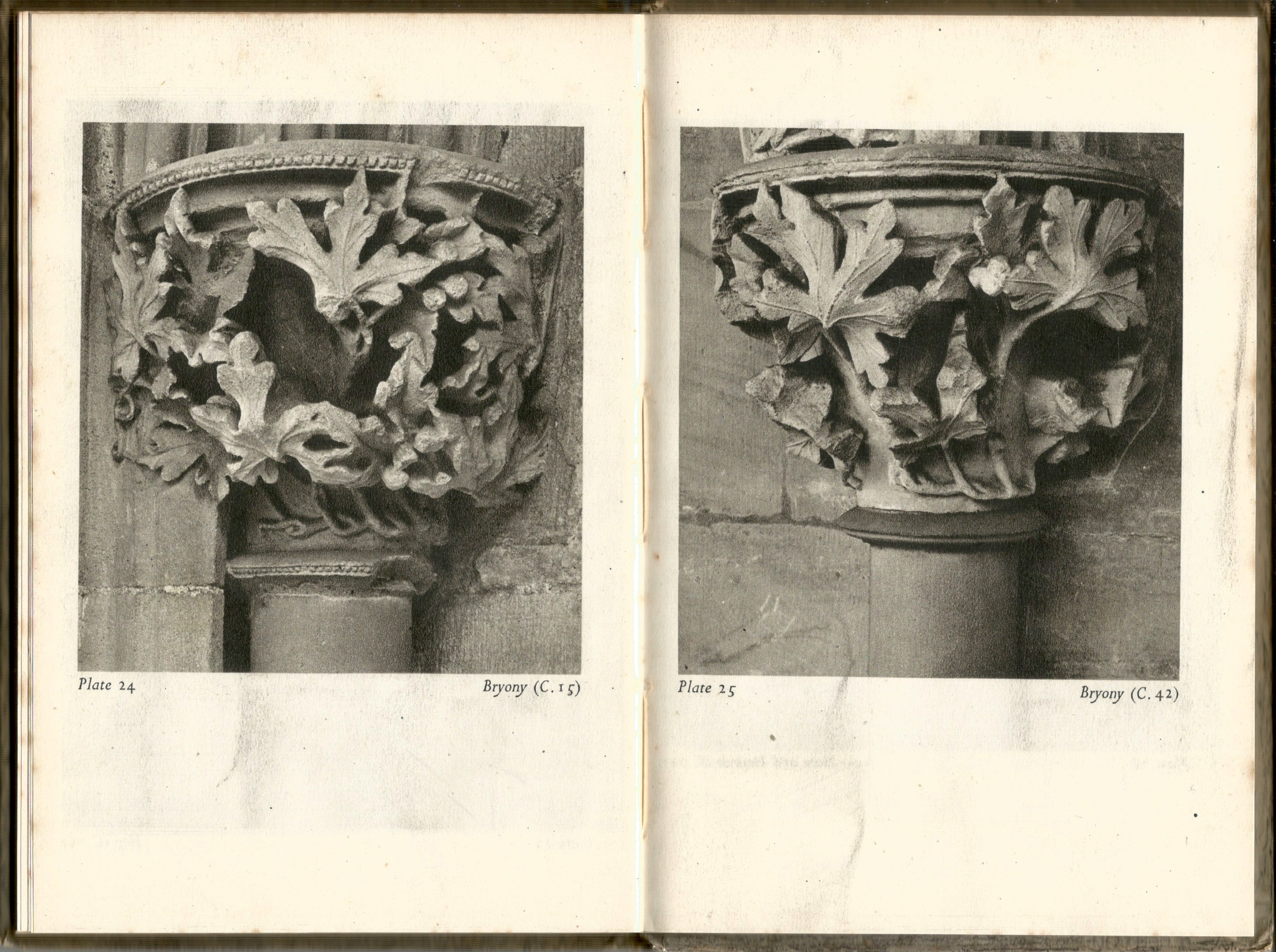

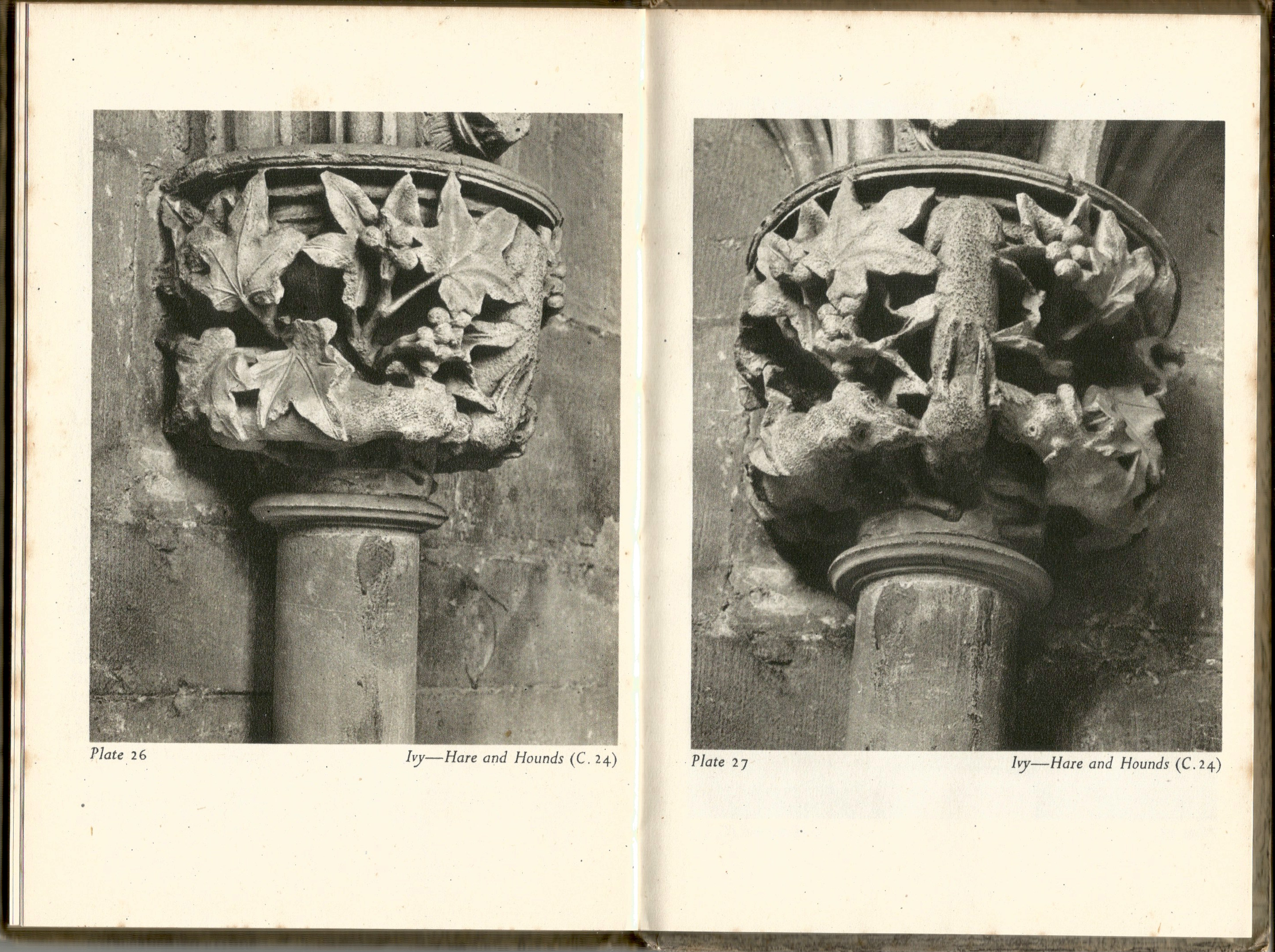

The leaves of Southwell to which this little book is devoted are the leaves which adorn the capitals of the columns of Southwell Chapter House. The Minster of Southwell lies eight miles west of Newark and fourteen miles north-east of Nottingham…

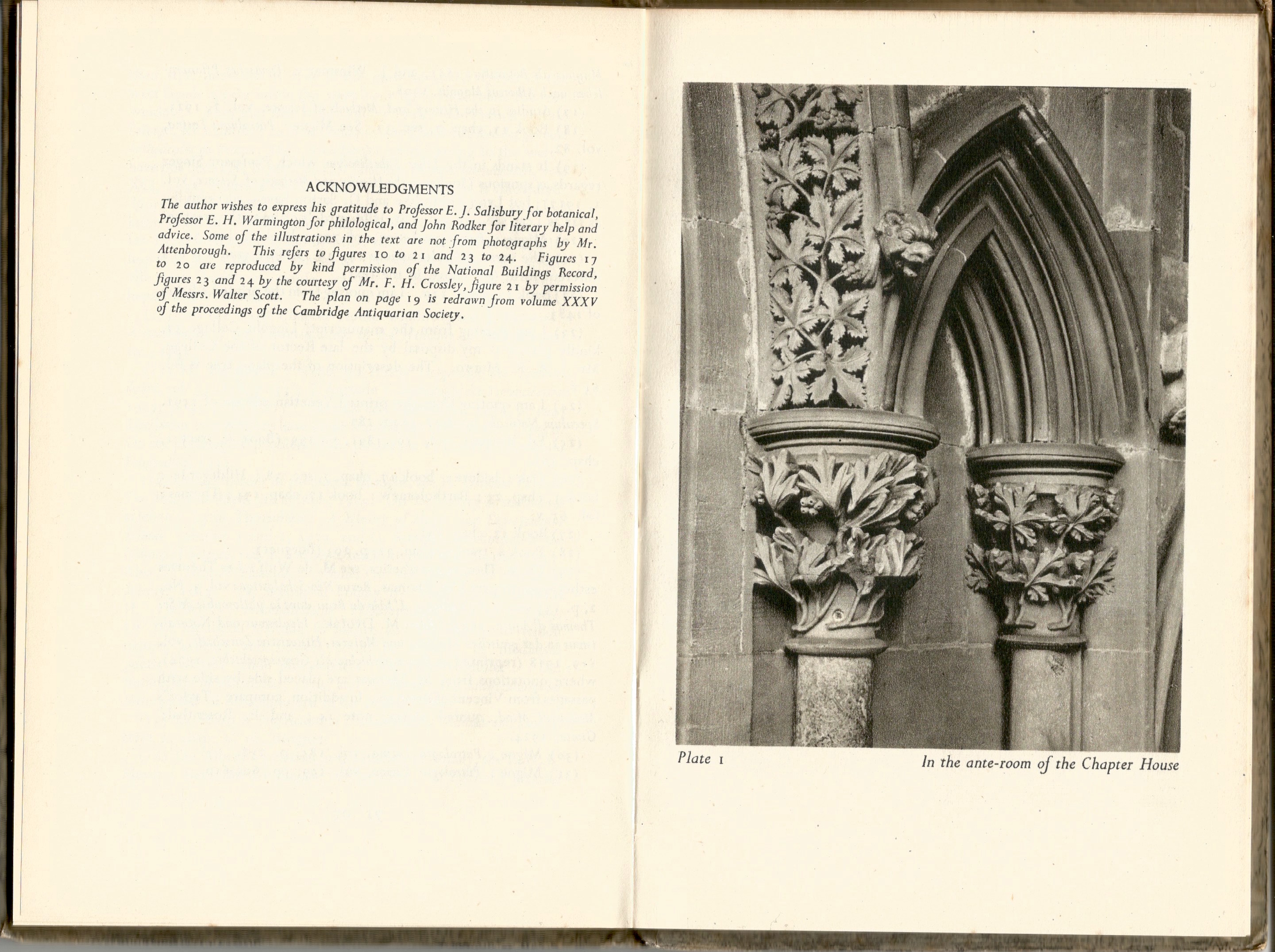

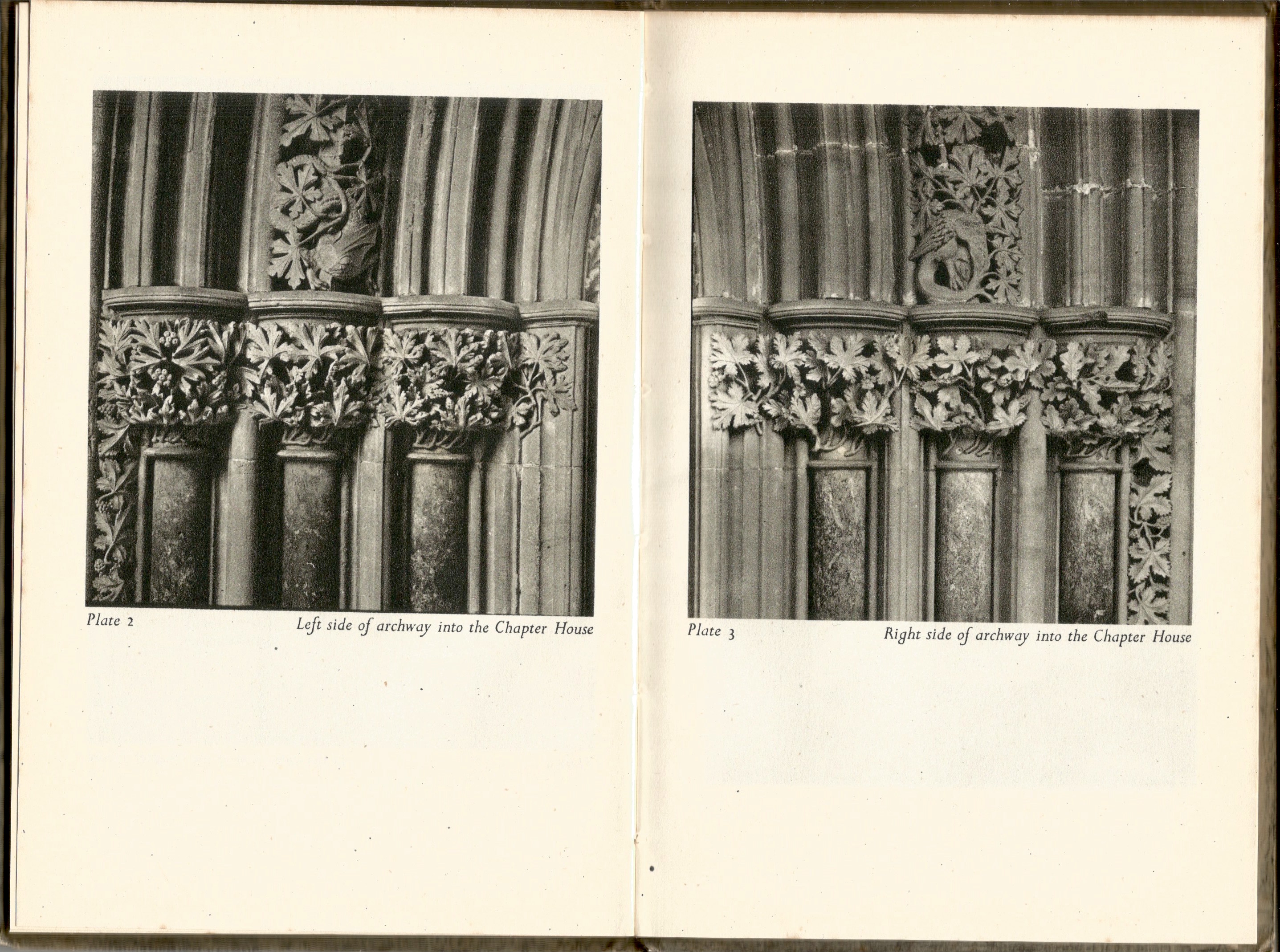

Balance of structure and decoration – a precarious, adventurous, proudly and self-consciously sustained balance – is one of the achievements of the Southwell capitals. Another is balance between nature and style. The copying of nature, for reasons ranging from primitive magic to sheer pride in imitative skill, is amongst the earliest functions of art. So is the desire to create expressive or decorative pattern out of material from nature.

At Southwell a degree of truth to life is reached which never between the first and the thirteenth century had been attempted in the West. Yet nowhere is the result that plodding, painful, pedantic pettiness of detail which spoils so much academic flower drawing and flower modelling of the nineteenth century. What saves the Southwell masters from this pitfall is their faith in the integrity of pattern.

Look at Plates 7, 8, 15, and 22, to choose a few of the most accomplished. They reveal how carefully the coherence of the pattern has been preserved in spite of the sway and scalloping of the leaves. Stone must remain stone and not attempt to masquerade as vegetable matter. However, the sculptor has nowhere gone so far as to force his leaves into decorative symmetry. Leaf, he felt, must remain leaf and never be reduced to abstract pattern.

He respected his material – stone – precisely as much as his subject – leaves. This is how he could achieve unity, while at the same time preserving variety; and this is how he could avoid tediousness, while confining himself to a far smaller number of botanical genera than the casual observer would realise… The impression the non-botanist receives is that the artist had a quick eye to observe the characteristic features of certain leaves, but no scientific ambition.

It never occurred to him, for instance, to keep to a uniform scale. Hawthorn leaves are no smaller than maple leaves. This confirms what has been said about his endeavour to achieve a synthesis of nature and style. The leaf, despite all his accuracy, remained to him a decorative motif. It is the decorator’s joy and skill, in association with the explorer’s, and in the end mastering the explorer’s, that accomplish the miracle of the Southwell carvings.

This quality can, of course, be fully appreciated only in front of the originals. And if these originals were in France rather than England they would doubtless draw numbers of educated English pilgrims to see them. Yet, being so close at hand, few know of them, and fewer still have really seen them. The plates to this book are meant to whet appetites. Sculpture is essentially three-dimensional. No reproduction in two dimensions can do it justice.

But Mr. Attenborough’s photographs (F.L. Attenborough was the father of Richard and David) of the Southwell capitals are an almost perfect interpretation. They have as much depth as the camera can achieve without smudging detail to obtain dramatic contrasts. Moreover, photographs have two advantages over originals which are not universally recognised or at least admitted. They focus the reader’s attention on important detail that he might miss on the actual spot, drawn from capital to capital by their multiple interest. And, as they lie on a table or are reproduced on the pages of a book, they can be enjoyed and studied with more comfort and leisure.

…And is not the balance of Southwell something deeper too than a balance of nature and style or of the imitative and the decorative? Is it not perhaps also a balance of God and World, the invisible and the visible? Could these leaves of the English countryside, with all their freshness, move us so deeply if they were not carved in that spirit which filled the saints and poets and thinkers of the thirteenth century, the spirit of religious respect for the loveliness of created nature?

The inexhaustible delight in live form that can be touched with worshipping fingers and felt with all senses is ennobled… by the conviction that so much beauty can exist only because God is in every man and beast, in every herb and stone. The Renaissance in the South two hundred years later was perhaps once again capable of such worship of beauty, but no firm faith was left to strengthen it.

Seen in this light, the leaves of Southwell assume a new significance as one of the purest symbols surviving in Britain of Western thought, our thought, in its loftiest mood.

This is a wonderful little book, a child of its time but ageing well and still beautiful. I am encouraged to visit Southwell Minster and its delightfully lively chapter house, with all its quick bright carvings.

I am especially grateful for this King Penguin. Here are some of our previous gifts –

Wood Engravings by Thomas Bewick, Portraits of Christ, British Shells,

Popular English Art, Chalk Flowers, Woodland Birds

※

Curiously, when looking back through my iCloud photo files I found these two images, a box of King Penguins from Julia Hallewell and a copy of Arboreal from Little Toller, each with the same date, 16 November 2016. They had both arrived on the same day!

I love a spooky coincidence!