High in the mountains of southern Corsica, on the road above Zonza and the Hippodrome de Viseo, described as Europe’s most elevated racetrack, we came to a hamlet of stone shelters with corrugated iron roofs, a collection of summerhouses and sheepfolds nestled beside the pass. We left the car at the Auberge du Col de Bavella, with the promise of a hearty meal upon our return.

One two-hour walk, waymarked red, leads through the Laricio pines, with trees over 150ft/46m high (the Genoese would come up here to harvest timber for masts), to the remarkable Trou de la Bombe or U Cumpuleddu, a curious 26ft/8m diameter hole eroded in the rock wall over the forest, that really does look as if someone had dropped a bomb in it; if you have a head for heights, you can even climb up to the edge for the dizzying views. Keep an eye out for the enormous lammergeiers who nest near here.

Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls: Corsica

But there were red waymarked paths in every direction and before long we were walking in circles.

Luckily the forest floor was littered with fallen pine cone compasses to show us the way.

A confusion of pine cones.

And then our first glimpse through the trees of the distant Trou de la Bombe.

The Aiguilles de Bavella, the great serrated granite ridge we’d seen when we started the walk, is a dominating presence visible for miles around. We’d first seen it from the plane when we arrived on the island (A Visit To Corsica), and again when we walked to the hill fort of Cucuruzzu.

We scrambled up and down the rocky path that eventually led to a small natural arena where it seemed many hiking trails converged. Sue waited here while I climbed up the final steep approach.

Watch me as I go, like an old mountain goat!

We came streaming over the rocks like ants funnelled through the eye of a needle.

But this was as close as I got. It was too congested and too vertical and too vertiginous.

From a distance I’d thought it might be better described as a stone picture frame, cadre en pierre or cadre sculpté seems nicely picturesque, like a natural portal or a porthole or a viewfinder; Trou de la Bombe sounds pretty violent, but up close Bomb Hole sounds about right. Click to play the video.

There it is again, between the trees. If I were a bird I’d fly right through it.

I’d brought with me a book of essays by W G Sebald. Four of them are about Corsica and in one, The Alps in the Sea, he writes about the loss of Corsica’s great trees; mankind’s fear of the natural world and his increasing destruction of it; the legend of St Julian and a world fallen from grace; and the sun going down over the horizon dividing what we can perceive from what no one has ever yet seen…

Once upon a time Corsica was entirely covered by forest. Storey by storey it grew for thousands of years in rivalry with itself, up to heights of fifty metres and more, and who knows, perhaps larger and larger species would have evolved, trees reaching to the sky, if the first settlers had not appeared and if, with the typical fear felt by their own kind for its place of origin, they had not steadily forced the forest back again.

The degradation of the most highly developed plant species is a process known to have begun near what we call the cradle of civilization. Most of the high forests that once grew all the way to the Dalmatian, Iberian and North African coasts had already been cut down by the beginning of the present era. Only in the interior of Corsica did a few forests of trees towering far taller than those of today remain, and they were still being described with awe by nineteenth-century travellers, although now they have almost entirely disappeared. Of the silver firs that were among the dominant tree species of Corsica in the Middle Ages, standing everywhere in the mists clinging to the mountains, on overshadowed slopes and in ravines, only a few relics are now left in the Marmano valley and the Forêt de Puntiello, and on a walk there a remembered image came into my mind of a forest in the Innerfern through which I had once gone as a child with my grandfather.

A history of the forests of France by Etienne de la Tour, published during the Second Empire, speaks of individual firs growing to a height of almost sixty metres during their lives of over a thousand years, and they, so de la Tour writes, are the last trees to convey some idea of the former grandeur of the European forests. He laments the destruction of the Corsican forests ‘par des exploitations mal conduites’ (‘by mismanaged exploitation’), which was already becoming a clear menace in his time. The stands of trees spared longest were those in the most inaccessible regions, for instance the great forest of Bavella, which covered the Corsican Dolomites between Sartène and Solenzara and was largely untouched until towards the end of the nineteenth century.

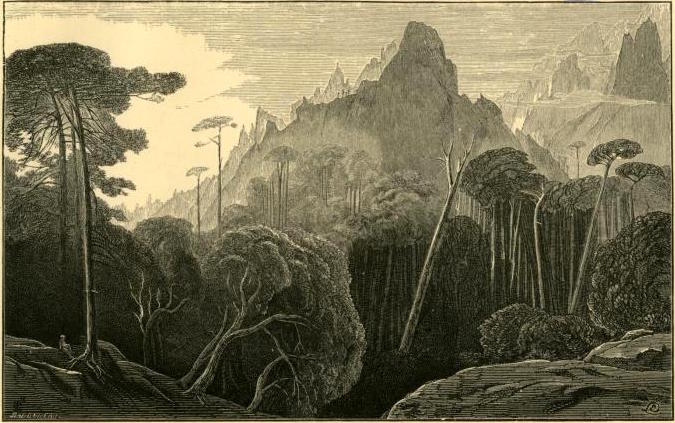

The English landscape painter and writer Edward Lear, who travelled in Corsica in the summer of 1876, wrote of the immense forests that then rose high from the blue twilight of the Solenzara valley and clambered up the steepest slopes, all the way to the vertical cliffs and precipices with their overhangs, cornices and upper terraces where smaller groups of trees stood like plumes on a helmet. On the more level surfaces at the head of the pass, the soft ground on which you walked was densely overgrown with all kinds of different bushes and herbs. Arbutus grew here, a great many ferns, heathers and juniper bushes, grasses, asphodels and dwarf cyclamen, and from all these low-growing plants rose the grey trunks of Laricio pines, their green parasols seeming to float free far, far above in the crystal-clear air.

‘At three the top of the pass… is reached,’ says Lear, ‘and here the real forest of Bavella commences, lying in a deep cup-like hollow between this and the opposite ridge, the north and south side of the valley being formed by the tremendous columns and peaks of granite… which stood up like two gigantic portions of a vast amphitheatre’, with the sea beyond them, and the Italian coast like a brush-stroke drawn on paper. These crags, he writes, ‘are doubly awful and magnificent now that one is close to them, and excepting the heights of Serbal and Sinai, they exceed in grandeur anything of the kind I have ever seen’. But Lear also comments on the timber carts drawn by fourteen or sixteen mules which even then were making their way along the sharply winding road, transporting single trunks a hundred to a hundred and twenty feet long and up to six feet in diameter, an observation that I found confirmed in 1879 by the ‘Dictionnaire de Géographie’ edited by Vivien de Saint Martin, in which the Dutch traveller and topographer Melchior van de Velde writes that he has never seen a finer forest than the forest of Bavella, not even in Switzerland, Lebanon or on the islands of Indochina.

‘Bavella est ce que j’ai vu de plus beau en fait de forêts,’ says van de Velde, adding this warning: ‘Seulement, si le touriste veut la voir dans sa gloire, qu’il se hâte! La hache s’y promène et Bavella s’en va!’ (‘Of the forests I have seen, Bavella is the loveliest… Only, if the tourist wishes to see it in its glory, he must make haste! The axe is abroad and Bavella is disappearing!’) And indeed, nothing in the Bavella area today is as it must have been then. It is true that when you first climb to the pass from the south, coming closer and closer to the rocky peaks, which are violet to purple in colour and are often surrounded halfway up by wreaths of vapour, and then look down from the edge of the Bocca into the Solenzara valley, it seems at first as if the wonderful forests praised by van de Velde and Lear were still standing. In truth, however, no trees grow here except those planted by the forestry department on the site of the great fire of the summer of 1960: slender conifers which cannot be imagined lasting a single human lifetime, let alone for dozens of generations.

The ground under these meagre pines is largely bare: I myself saw not the slightest trace of the wealth of game mentioned by earlier travellers – ‘le gibier y abonde,’ writes van de Velde. Ibex were once extremely abundant here, eagles and vultures soared above the rock-slides, hundreds of siskin and finches darted through the canopy of the forest, quail and partridge nested under the low shrubs, and butterflies fluttered everywhere around…

number nine, number nine

The road dropped sharply over the escarpment. Immediately below the pass was a group of stone huts set close together on little terraces. They were primitive one-storeyed cabins with wooden roofs, making a settlement where women sat in doorways and children played in the rocks and goats and pigs and chickens nibbled and rootled and pecked the turf. The cries of children and the yapping of dogs sounded tragically feeble in the vastness of the air.

‘We come up here every summer,’ she told me. And so I learned that this was a peasants’ holiday resort, that the cabins belonged to the inhabitants of the subtropical east coast plains who moved up here with their children and livestock during the hottest months of the year. While we were talking a truck came grinding out of the abyss. ‘You see, there’s a new lot arriving, they all come from the same village,’ the woman explained. They were so crowded in the truck that they were all standing, the women carrying their babies and the men their guns, and as they arrived they were all cheering. The Corsicans, I thought, might not be a gay people, but they had their own deep fantastic pleasures.

Granite Island, A Portrait of Corsica: Dorothy Carrington

※

We left Bavella descending towards Zonza and soon found a belvedere with a vast panorama looking towards Monte Incudine. Please try to imagine these 3 photos stitched side by side from left to right.

Further down the road, a wayside oak and a universe in its branches, worth stopping for.

The Aiguilles de Bavella

The Alps in the Sea