We just received a wonderful gift in the post. A message from beyond the grave. Before his death in January last year, John Hubbard had been putting together what he liked to call his self-curated retrospective; a collection of images with commentaries from his diary gathered together in a book celebrating his lifelong devotion to painting. Remaking Landscape is a thing of beauty.

Ouirgane, 1971, Oil on canvas, 165 x 178 cm, Private collection

Here are some of my favourite pages…

John Hubbard’s studio, Chilcombe House, Dorset, 1990s

Double Reflections, 1969, Oil on canvas, two panels, each 190 x 165 cm, Private collection

This is one of the earliest of my two-part (or two-panel) paintings. These were much influenced by Japanese screens, but they particularly appealed because they allowed me to develop the sections into much larger paintings. I also love painting screens, but have only completed one [Four-Panel Screen, 1978]. Other artists, such as Gustav Klimt and Pierre Bonnard, have made screens, but they have never really caught on as a vehicle for painting.

In The High Atlas, 1969, Oil on canvas, 178 x 165 cm, Arts Council of Great Britain

This is my first Moroccan painting. The Atlas Mountains reveal themselves across the broad lowlands surrounding Marrakech, their snowy peaks gleaming in the distance. Their power and mystery increase as one approaches their lower slopes. They are populated mountains with Berber villages scattered among them, along with terraces and bubbling irrigation canals that play such a key role in their agriculture. The mountains resonate to the voices of women and the chanting of children in the miniature madrasas. In the numerous woodlands the light is fractured through a rich tangle of leaves and trees while the open areas, often alongside clear streams, bake silently, their quiet only disturbed by domestic animals or the movement of gum leaves.

Mysterious Passes No.3, 1971, Oil on canvas, two panels, overall 198 x 254 cm

One of a series of large, often double-panelled paintings celebrating the almost mystical atmosphere of certain unique passes in the Atlas Mountains, which are often simply changes in ground level or a break in the tree cover. The sense of awe is moving and mysterious and best absorbed in quiet.

Rock Growth: Haytor (No.2), 1979, Oil on paper, 76 x 76 cm

It’s an easy drive from West Dorset to Dartmoor. The majestic sweep of the tors and hills appear on the horizon soon after Exeter, and Haytor is among the first. What is unique about Haytor is that its quarries were once serviced by a granite railway, some tracks of which still exist. The quarry is sunk into the moor, which offers some protection during storms. Parts of the quarry are rough, others are almost architectural.

Rocks also make sensible homes for wildlife and vegetation, and rock growth has found an important place in my work.

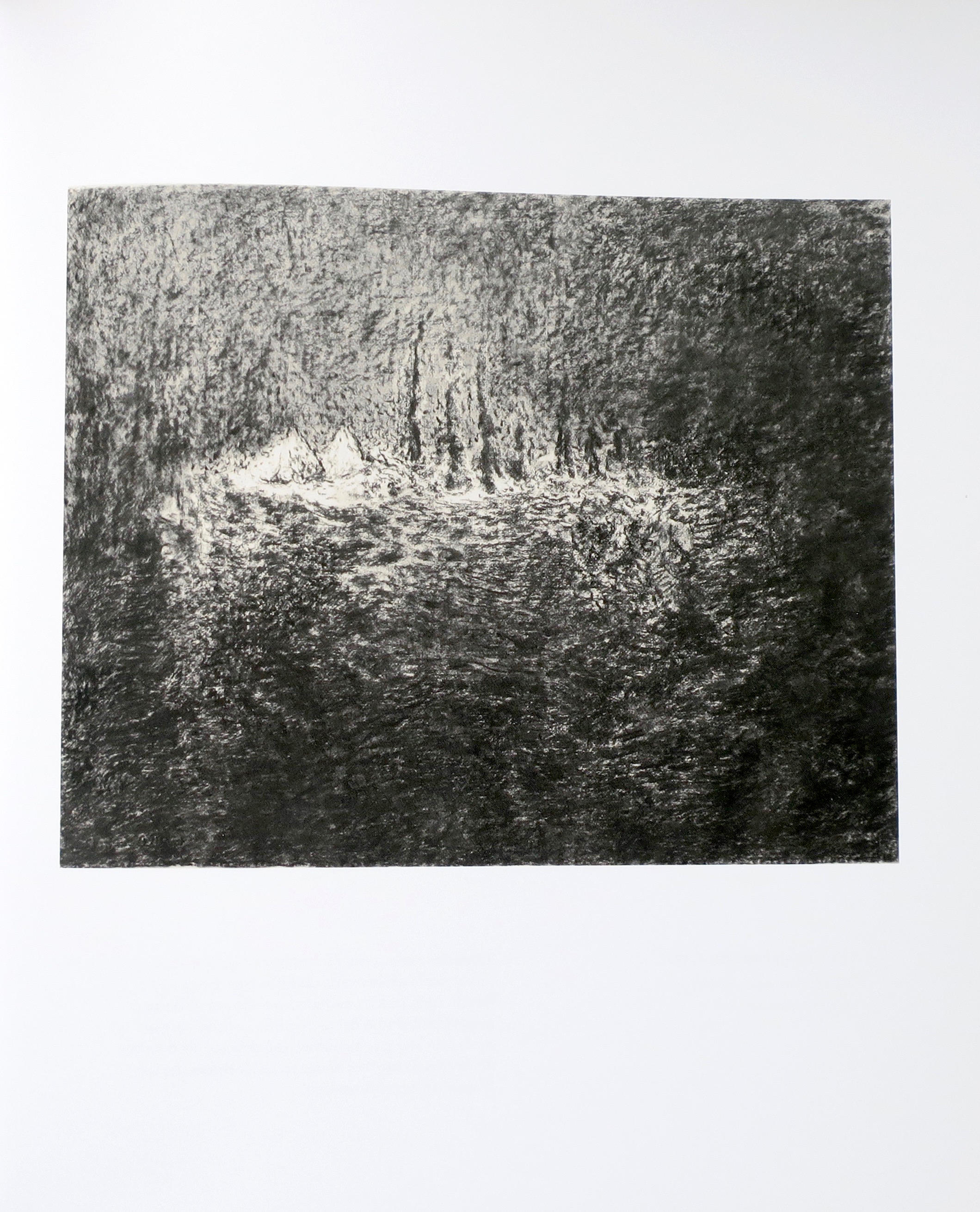

Inhabited Stone No.2, 1976, Charcoal on paper, 56 x 70 cm

This has long been a favourite drawing of mine, partly because of the pleasure I felt on finding the actual stone and partly because it reminds me so poignantly of the nature fantasies of my youth. I journeyed to Anglesey at the suggestion of an artist friend and, before the weather collapsed entirely, found several intriguing stones to draw. This I think is the best, with its suggestion either of still figures or a vanishing city.

White Sea, 1981, Oil on canvas, 152 x 152 cm, Private Collection

Most of the paintings I’ve made based on Porthmeor Beach in St Ives were determined efforts to open up and expand the vista one has when approaching it from above or near Tate St Ives. It seems almost to be a vertical descent by parachute, with the beach itself flying away below you, its edges defined by incoming waves on one side, the former warehouses and studios on the other. I have come to believe that there are really too many excitements with this view, making it almost impossible to convey its physical splendour. Here, I’ve come right down on to the beach itself, to where the rocks and sea wage constant tug-of-war. I’m pleased that ‘White Sea’ has now settled in Cornwall.

I first came to St Ives in 1958. Having sailed from New York, I was so struck by the beauty of the Devon coastline as we steamed towards Plymouth that I wanted to stay but was informed that I had to have a destination before I could leave the harbour. As I didn’t know the names of any towns in Devon or Cornwall, I was stuck, until the desk clerk asked ‘What’s your job?’ ‘Artist,’ I replied. ‘That’s fine,’ he said, ‘St Ives,’ and I was immediately dispatched on the train. I found a room in a small hotel, bought sketch-books, pencils and so forth and set out to spend several lovely days exploring the area. I’d met no one, and was about to leave when I walked into the Sloop, a pub near the harbour, and promptly met Bill Redgrave, Karl Weschke and Bryan Wynter.

Over the next few years I became friendly with Terry Frost, Patrick Heron and particularly Peter Lanyon, who invited me to his studio and took me to a wonderful exhibition of Stanhope Forbes in Penzance. I found Peter’s opinions about painting marvellously refreshing, as well as his interest in many other forms of art.

Pink Stones, Les Seguins, 1981, Oil on canvas, 178 x 193 cm

Les Seguins is the name of a relatively small limestone valley a short distance outside Aix-en-Provence. While never a subject for Cézanne, it is one of the places touched on in his late group of paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire. The stones there aren’t pink, but some of Cézanne’s middle-ground oils suggest pinkiness, for example ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From Les Lauves’. In several paintings from this magnificent series, sections of the landscape seem to possess their own gravity and almost hover in space. That is really the subject of this painting.

Encrusted Stones, Vaucluse, 1981, Oil on canvas, 183 x 173, Private collection

Not everything in Provence bakes continuously in the sun. These stones were in one of the quite sheltered valleys leading north from Apt towards the eastern slopes of Mont Ventoux, in the vibrant Vaucluse landscape. Painted in the same year as ‘Pink Stones, Les Seguins’, it has a bosky feel, with the encrusting foliage being both clothing and a reminder that these are living organisms.

Tresco No.5, 1984, Oil on canvas, 193 x 188 cm

It is terribly important not to go to a place which has been warmly recommended as subject matter until you can be pretty sure that it will be the place for you. Both Tony O’Malley and Patrick Heron were filled with enthusiasm for Tresco and the Isles of Scilly in general. I finally got to Tresco in 1984 and was immediately excited. The great variety of trees and profusion of exotically coloured plants at Abbey Garden was astonishing, particularly then, before the terrible storm of 1987 severely damaged the garden. I was particularly attracted by the larger-than-life types of vegetation that lurked everywhere, giving parts of the garden a surreal feeling.

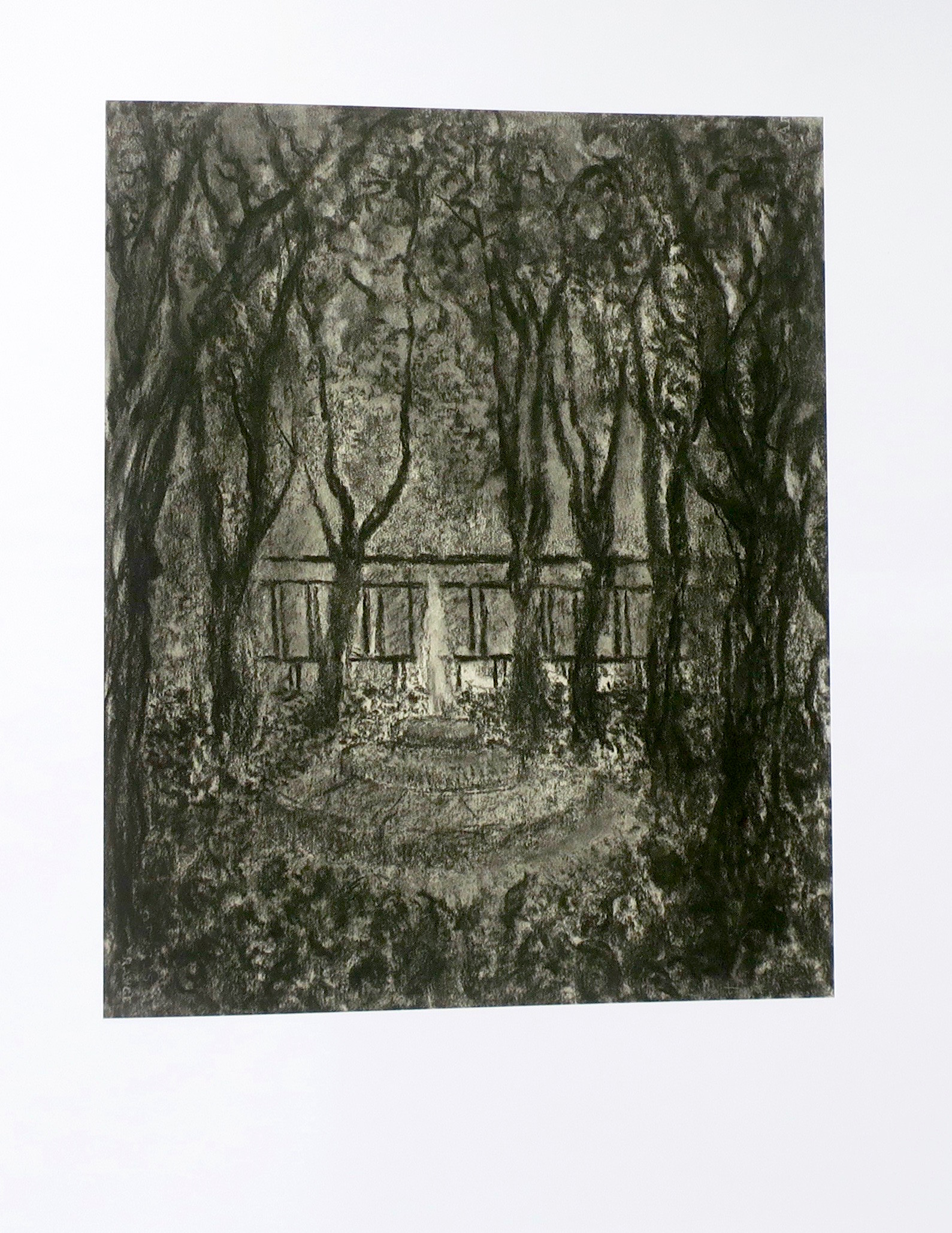

Carol’s Garden, 1988, Charcoal on paper, 69 x 56 cm

New Harmony is a utopian community in south-west Indiana, a mix of gardens, old and new buildings (including Philip Johnson’s Roofless Church and Richard Meier’s Atheneum), woods and farmland. In 1987 I met Jane Owen in New York. She had been married to the heir of New Harmony and invited me to make a project there. My suggestion was to produce a book, including a brief history, with etchings based on places in the village. Jane liked the idea, so we started forthwith.

I first saw New Harmony on a cold afternoon in December 1987, when it looked like a delicate, enduring lacework of wooden houses, trees, fences and cabins balanced between hard, flat earth and ice-blue sky. At that point, I felt colour to be extraneous, and an afternoon and evening spent walking about its streets and paths, exploring wintry fields and secret gardens illuminated by little lights that winked back at the stars, confirmed that first impression. New Harmony, I thought, would best be portrayed in print, in black and white.

Caryl and I settled into the Poet’s House in late September the following year, when high summer still persisted. We spent six weeks there and loved every minute. I began preparations for my ‘portrait’ by making large charcoal drawings in situ of places that caught my interest, as well as a number of small pastels. Later, back in Dorset, these became a series of 14 etchings, made in collaboration with the great printer Jack Shirreff. ‘Portrait of New Harmony’ was published in 1990, and its etchings and related pastels and charcoal drawings exhibited in a US travelling show which also came to London.

The New Harmony etchings can be seen here – From The Poet’s House.

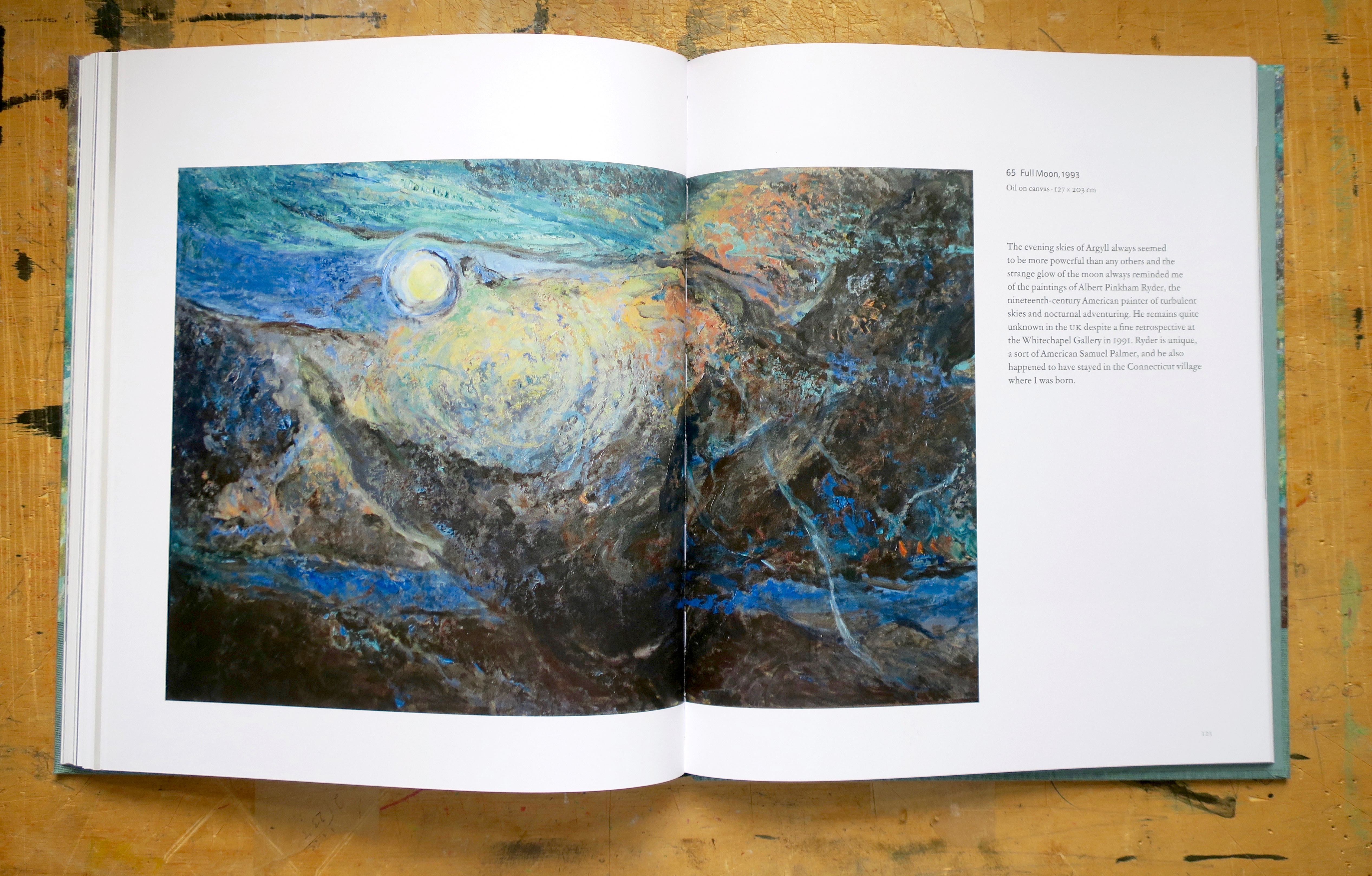

Full Moon, 1993, Oil on canvas, 127 x 203 cm

The evening skies of Argyll always seemed to be more powerful than any others and the strange glow of the moon always reminded me of the paintings of Albert Pinkham Ryder, the nineteenth-century American painter of turbulent skies and nocturnal adventuring. He remains quite unknown in the UK despite a fine retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1991. Ryder is unique, a sort of American Samuel Palmer, and he also happened to have stayed in the Connecticut village where I was born.

Change, 2002, Oil on canvas, 127 x 142

This might be termed a fleshed-out arabesque. It is a sort of rush-hour water painting, each element vying with the next to create a busy bubbling panorama, colourful, lively and joyous.

John and Caryl Hubbard’s garden, Chilcombe House, Dorset, 2009

※

We felt lucky to have met John and we always looked forward to his visits, whether he came to get something framed or to bring us pictures to exhibit, he always brought wise words and his special kind of warm attention that made us glad to know him.

※

John Hubbard: Remaking Landscape

Catching up on Frames of Reference this morning, learning of John Hubbard and viewing his work has been a delight. On an archive style website I found a short film of the man himself talking about painting and singing American folk songs:

Fantastic! Thanks Susie. There’s more here – http://blog.rowleygallery.co.uk/for-john-hubbard/

Wandering my way through all the John Hubbard words and pictures on Frames of Reference, a good Friday so far SX