Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde was an exhibition last year at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. It then transferred to the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn and it will soon arrive at Tate Modern in London. Here are a few photos of its appearance at the Stedelijk.

Shroud of Christ, 1908, gouache on cardboard, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

…In April 1907, an exhibition of the Symbolist art group Blue Rose opened in Moscow. Impressed by their work, Malevich was inspired to paint decorative Symbolist gouaches like ‘Shroud of Christ’…reminiscent of icons. However, this stylistic foray did not last…

Self-Portrait, 1909-10, varnished gouache, watercolour and pencil on paper, Private Collection.

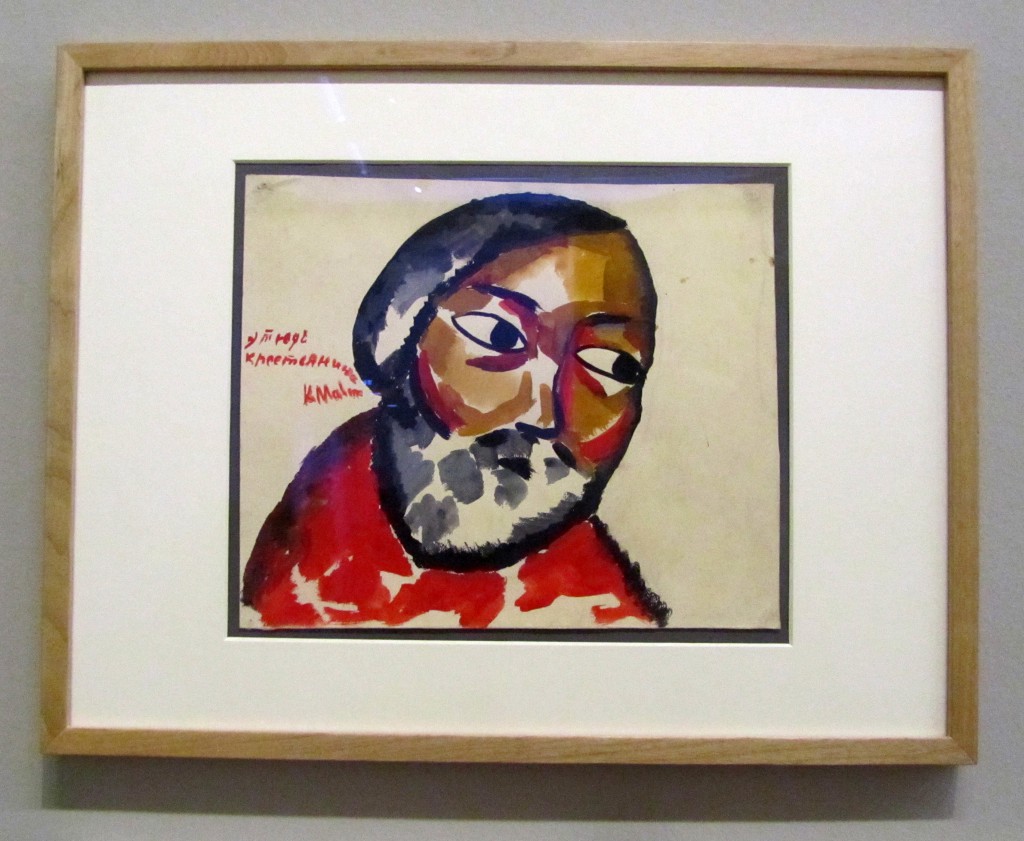

Study of a Peasant, 1911, gouache on paper, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris.

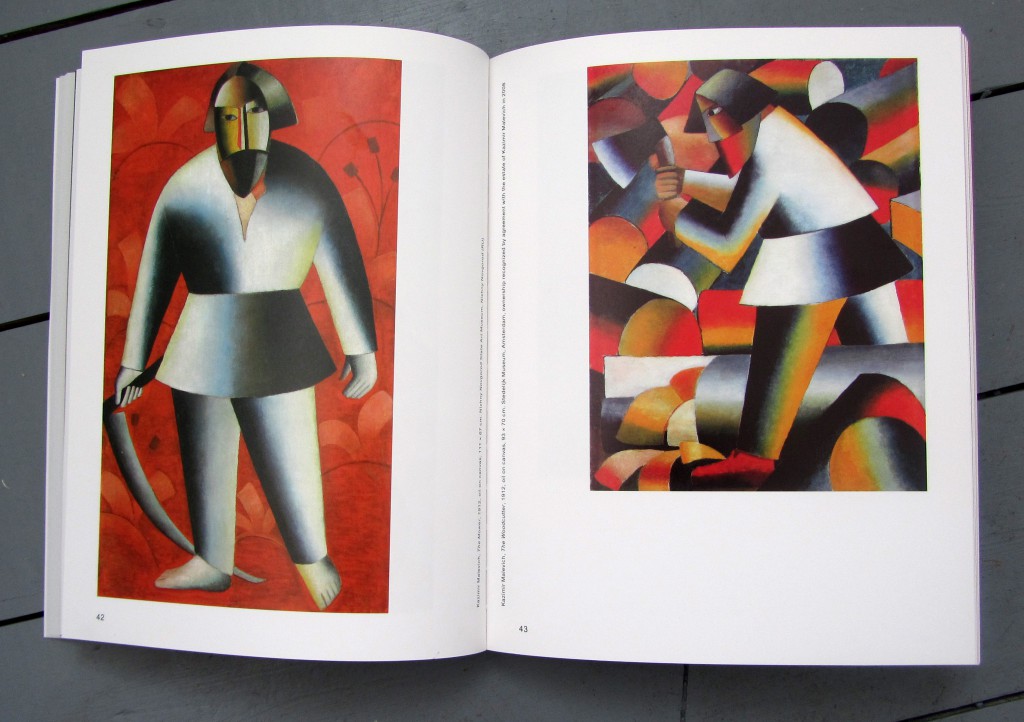

…In 1910, Malevich began to paint, in a Neo-Primitivist style, farmers at work, harvesting crops or threshing grain… But again his artistic development entered a phase of rapid change. There is a marked difference between the expressive ‘Study of a Peasant’, formerly in the possession of Wassily Kandinsky, and ‘The Mower’ or ‘The Woodcutter’, both of 1912. In these paintings, which explore rural and everyday subjects, even the human figure is secondary to the rhythmical composition of cylindrical shapes…

The Mower, 1912, oil on canvas, Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum, Nizhny Novgorod and The Woodcutter, 1912, oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, from the exhibition catalogue.

Cubo-Futurist Composition with Piano, 1913-14, oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

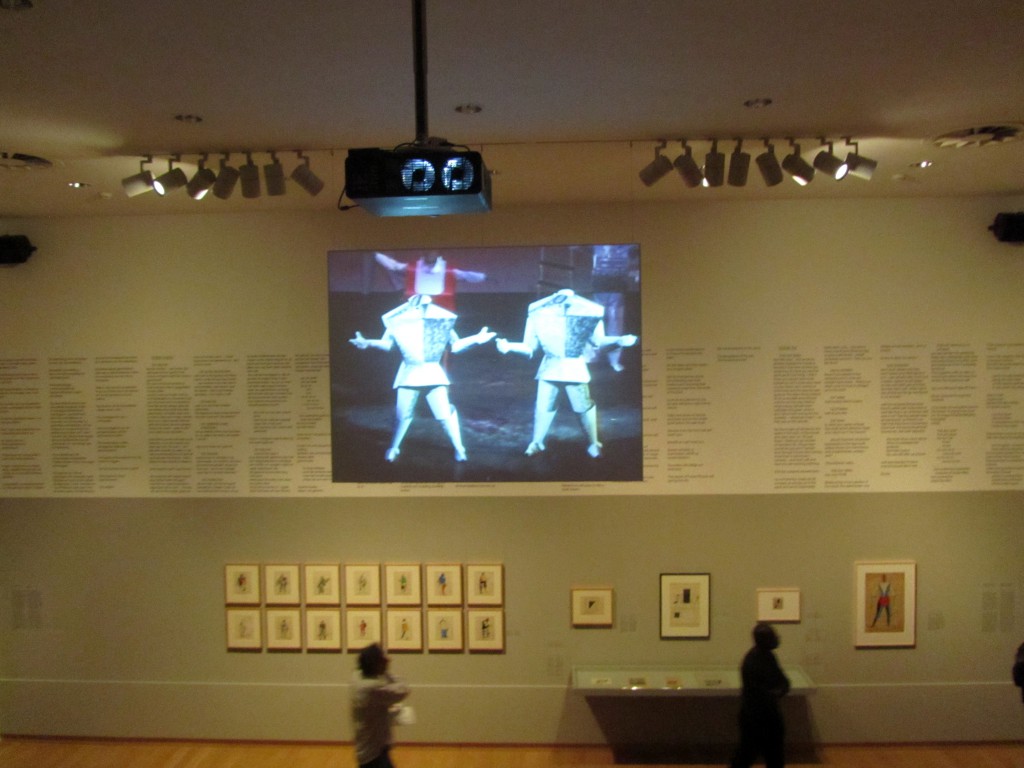

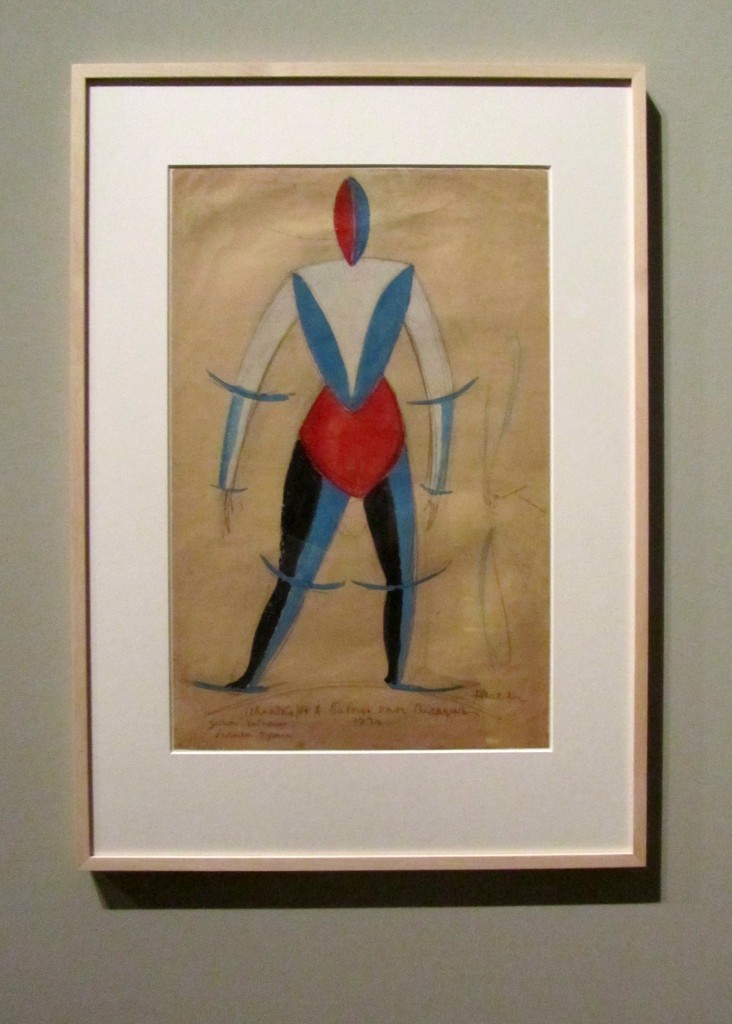

Aviator in Victory over the Sun, 1913, gouache on paper, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

In the opera ‘Victory over the Sun’, the People of the Future battle the sun. Hailing from the future, these characters were meant to look as though they were part of a new, limitless world that would emerge once the era of the sun had ended. To accompany the new Zaum language of the libretto by Kruchenykh, Malevich created decors and costumes in a visual form of Zaum. He devised radical and non-representational designs that deformed the bodies of the actors by covering them with elementary shapes and bright hues… Despite the hypermodern figures and sleek metal shapes, this costume design also integrates medieval and peasant motifs.

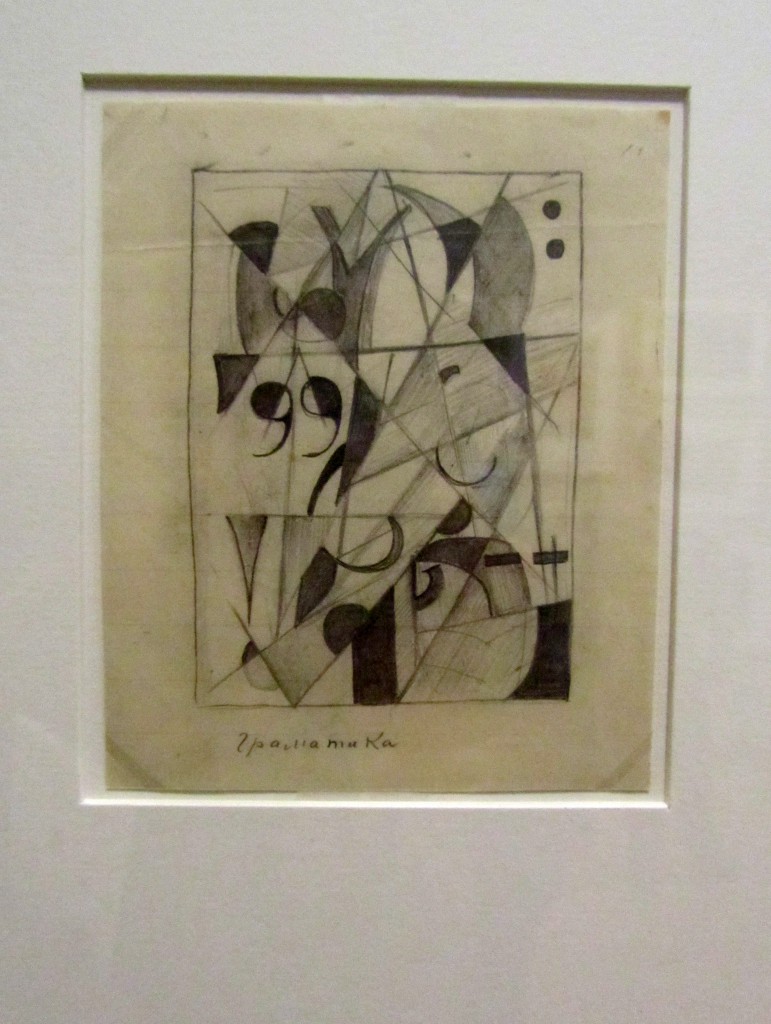

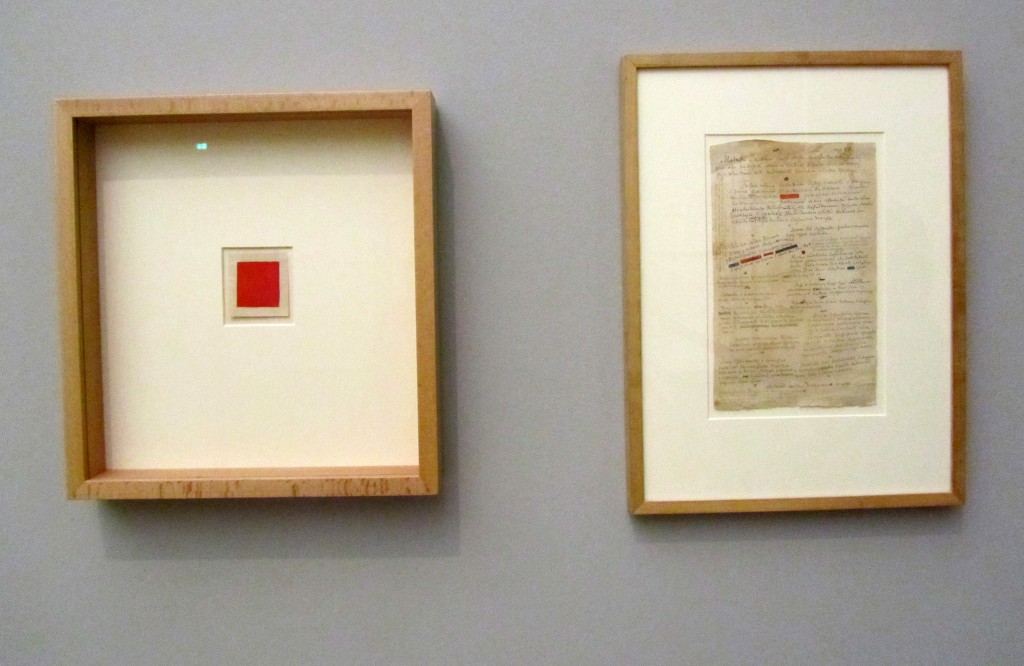

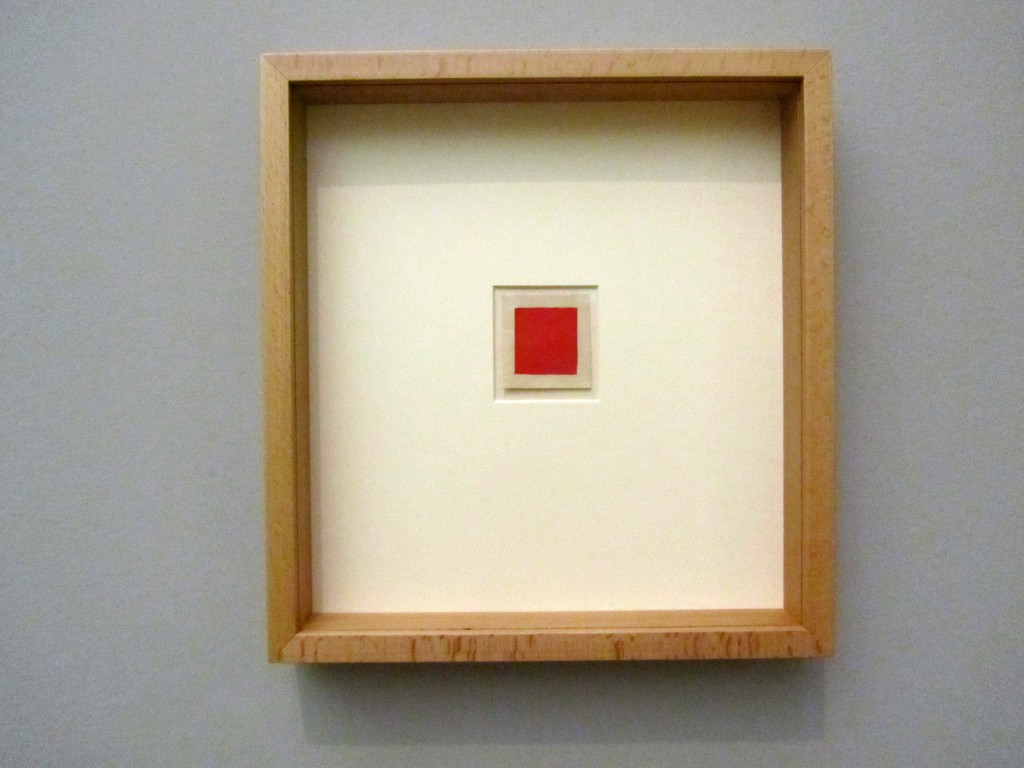

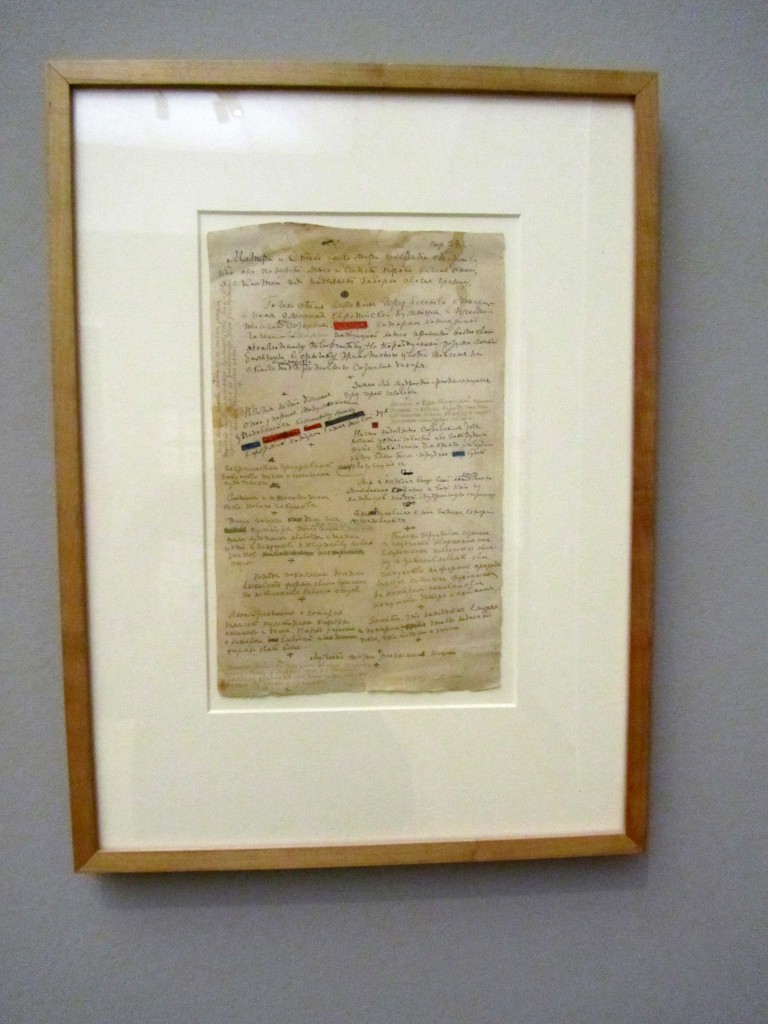

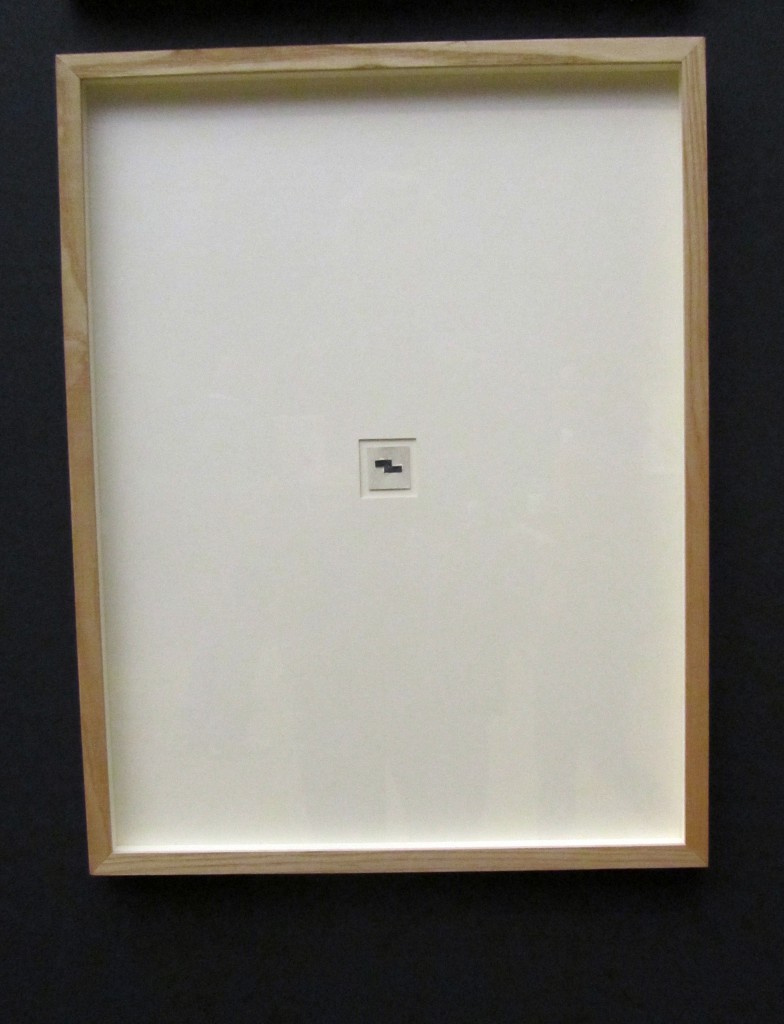

Grammar, 1913, pencil on lined paper, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

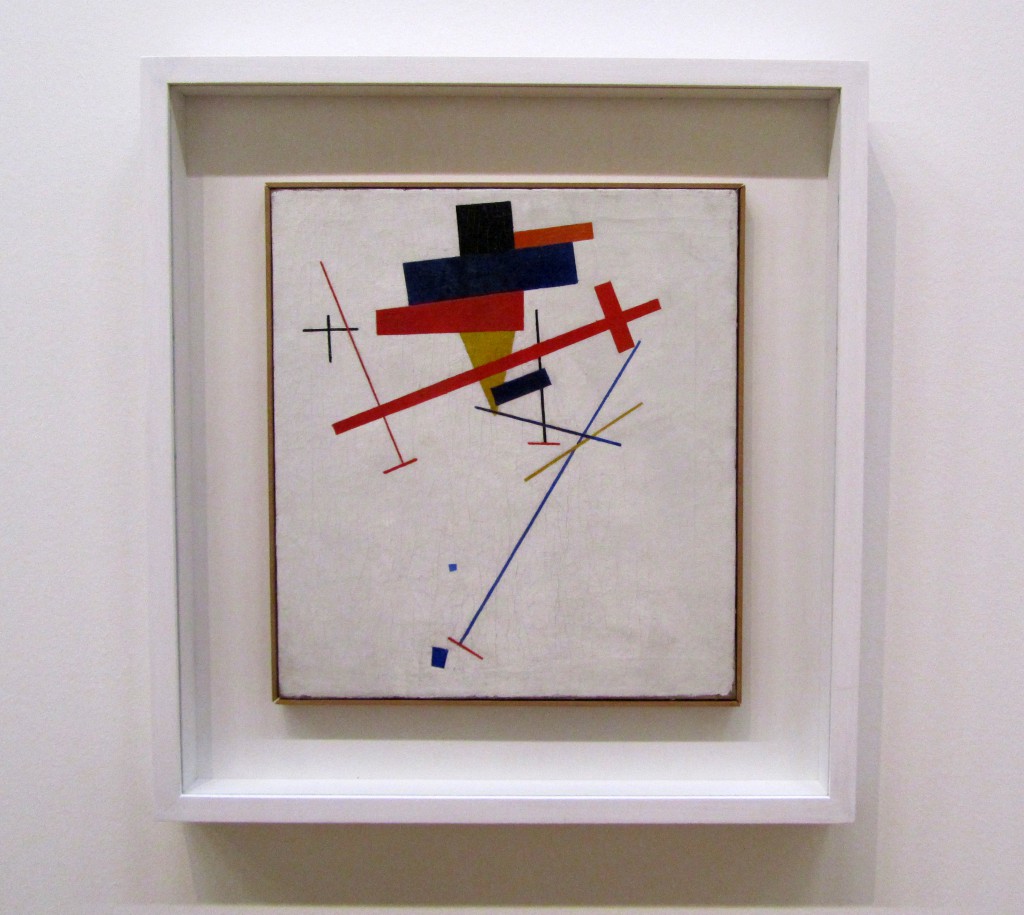

On 19 December 1915, the exhibition ‘The Last Futuristic Exhibition of Paintings “0,10”‘ opened in Petrograd… Suprematism, which asserted the supremacy of color and form in painting. For Malevich, this was ‘painterly realism’ precisely because it contained no recognizable pictorial elements. Suprematism was to be the art of paint on canvas – of pure creation – and not of the imitation of visible reality… In a high corner of the room, the place where sacred icons traditionally hang in Russian homes, Malevich installed his ‘Black Square’… the archetype of Suprematism, ‘the face of the new art’ and ‘the first step toward pure creation’.

Magnetic Construction, 1916, oil on canvas, Wilhelm-Hack Museum, Ludwigshafen am Rhein.

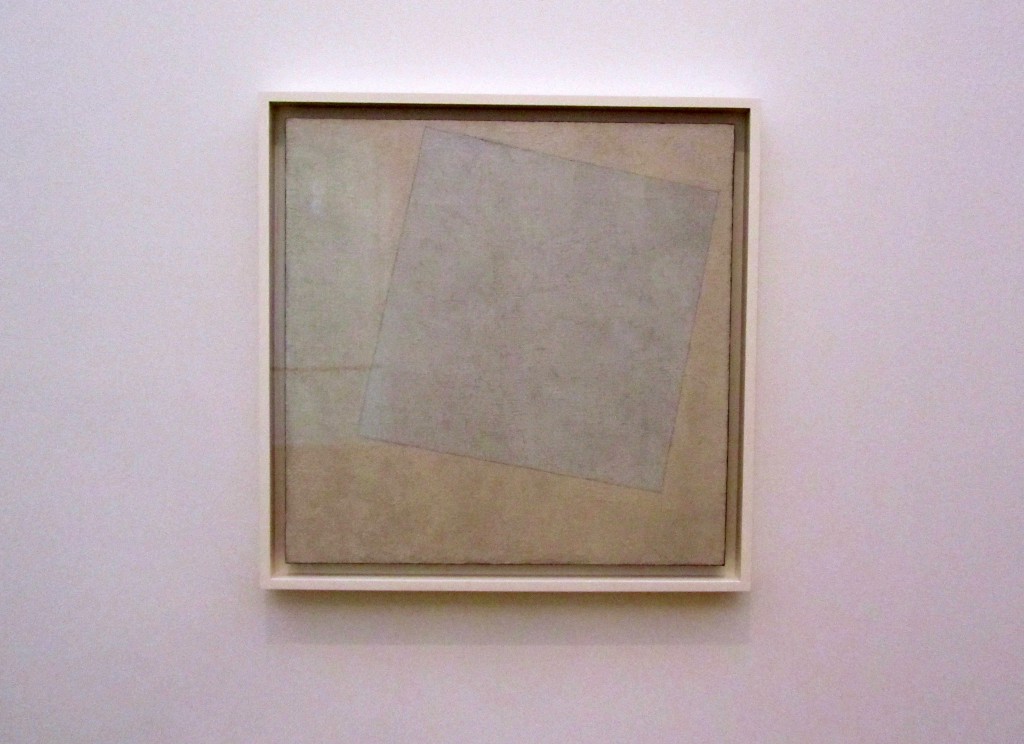

Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

‘Suprematist Composition: White on White’ is one of a series of five white-on-white paintings in which Malevich reached the pinnacle of his exploration of painting. Having already removed all pictorial allusions to space, perspective, and volume, he here also dispensed with color, which he saw as the last fundamental element of traditional painting. The surface, richly textured with brushstrokes, reveals the hand of the artist in a work that otherwise might be considered impersonal. By superimposing two very different shades of white, the artist aspired to layer infinity upon infinity and thereby evoke the cosmos. “Swim in the white free abyss, infinity is before you,” he wrote during an exhibition of the work in 1919. Malevich felt that he had finally freed himself from the conventions of painting. Inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917, Malevich believed that a new era of spiritual freedom was soon to dawn.

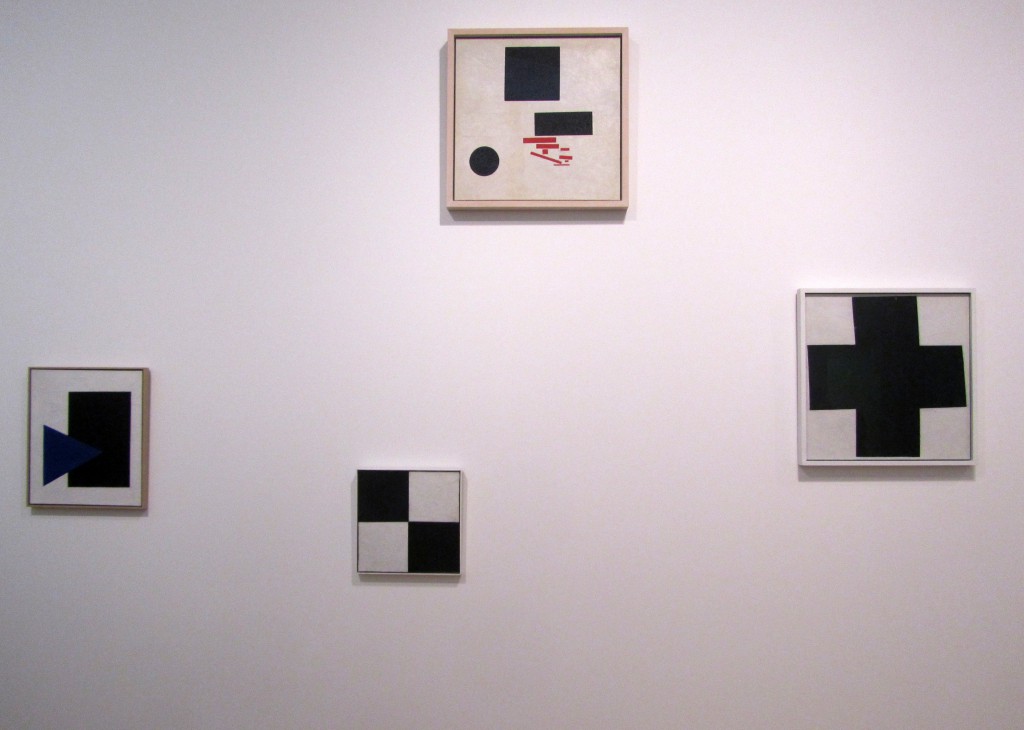

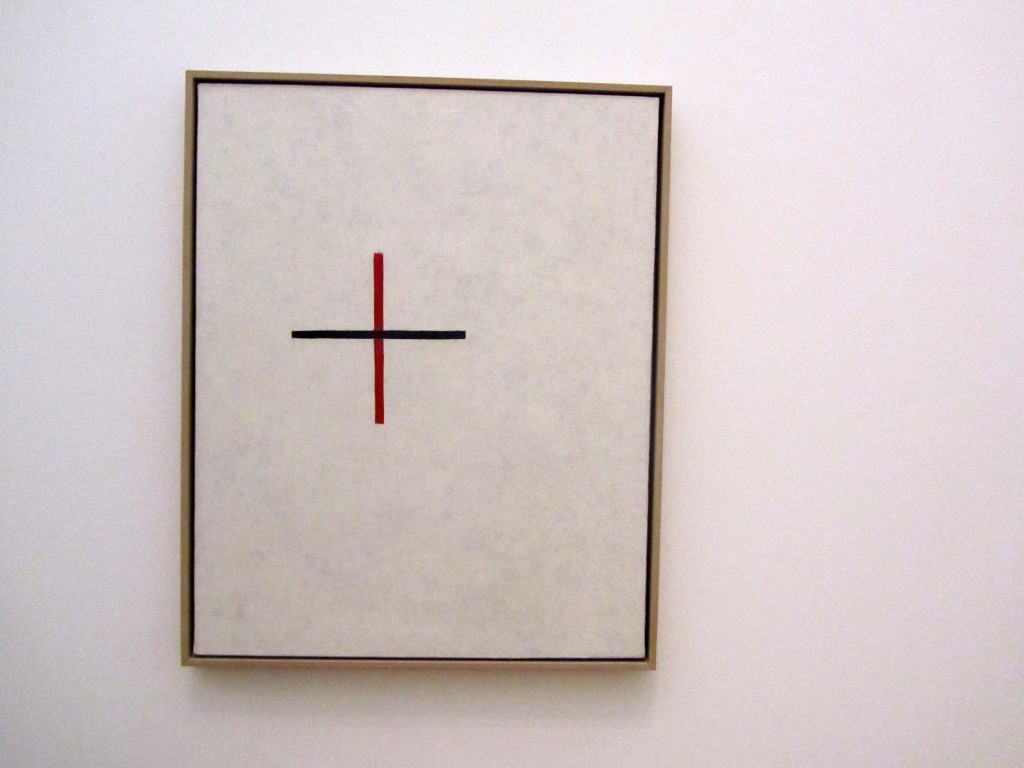

Suprematist Cross (Small Cross in Black over Red on White), 1920-27, Stedelijk Museum.

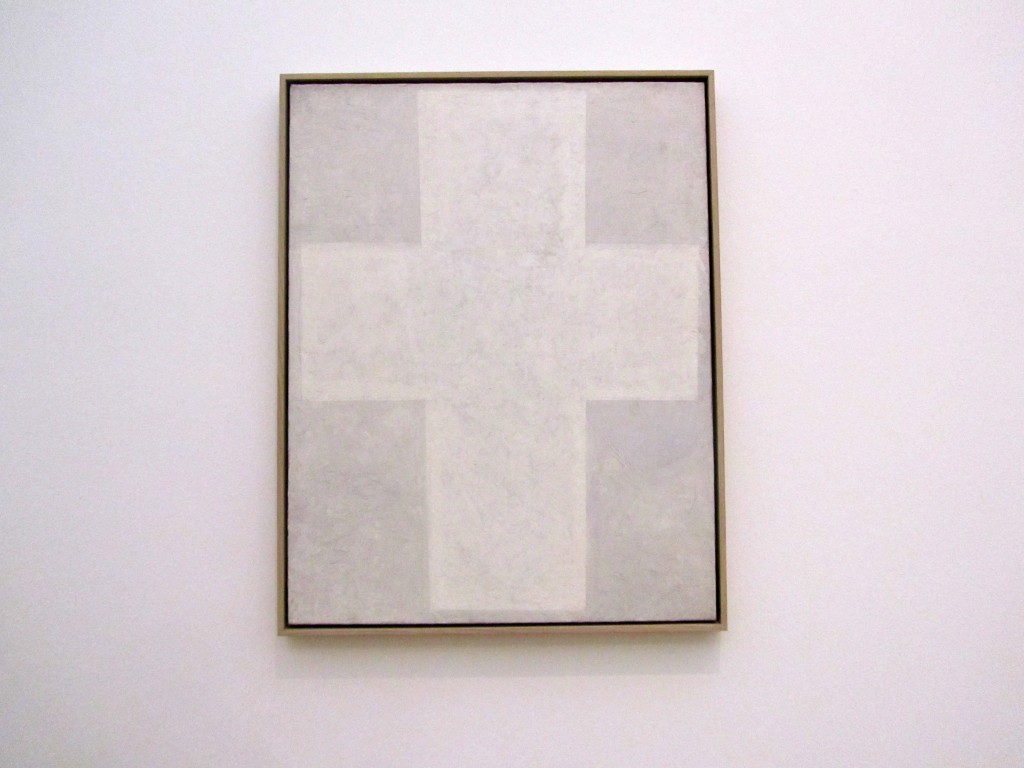

White Suprematist Cross, 1920-21, oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

For Malevich, Suprematism meant liberating painting from the burden of recognizable images. He described his Suprematist works as non-objective, but never as abstract… the colors and shapes speak their own language: they are the expression of the artist’s belief that everything is in motion… Suprematist compositions depicted the dynamics of planets, squirming bacteria, the living and not living, and visible and invisible nature in ‘pure’ color and form.

Hieratic Suprematist Cross, 1920-21, oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

‘Mothers and children of the world, beware of your homeland, because it will eat you and drink the blood of your children, and with their bones they will build a fence around their borders…’

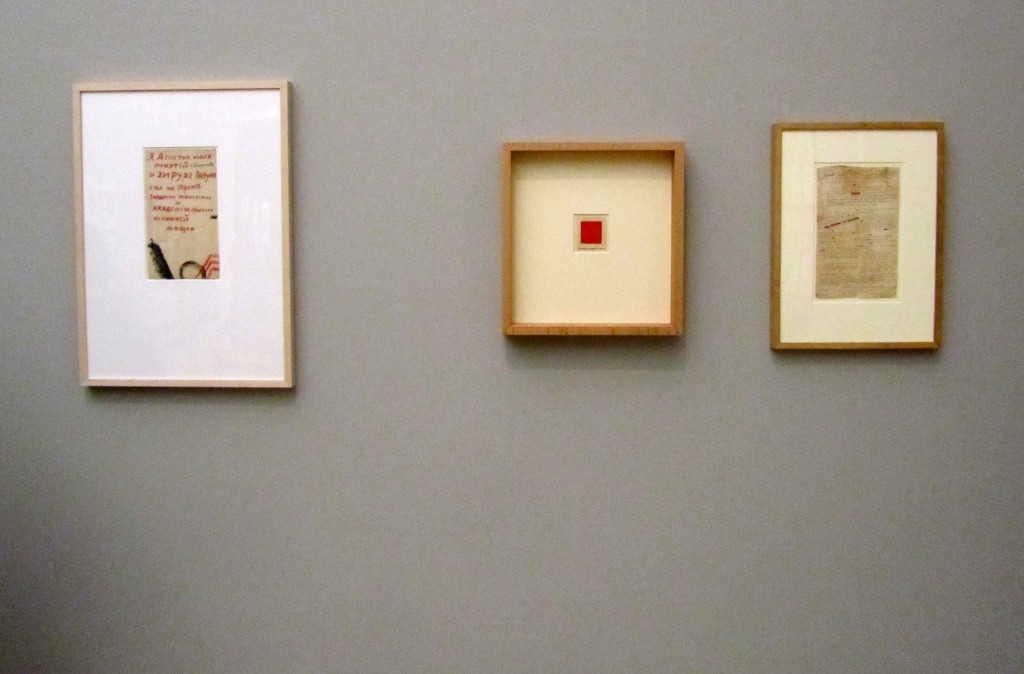

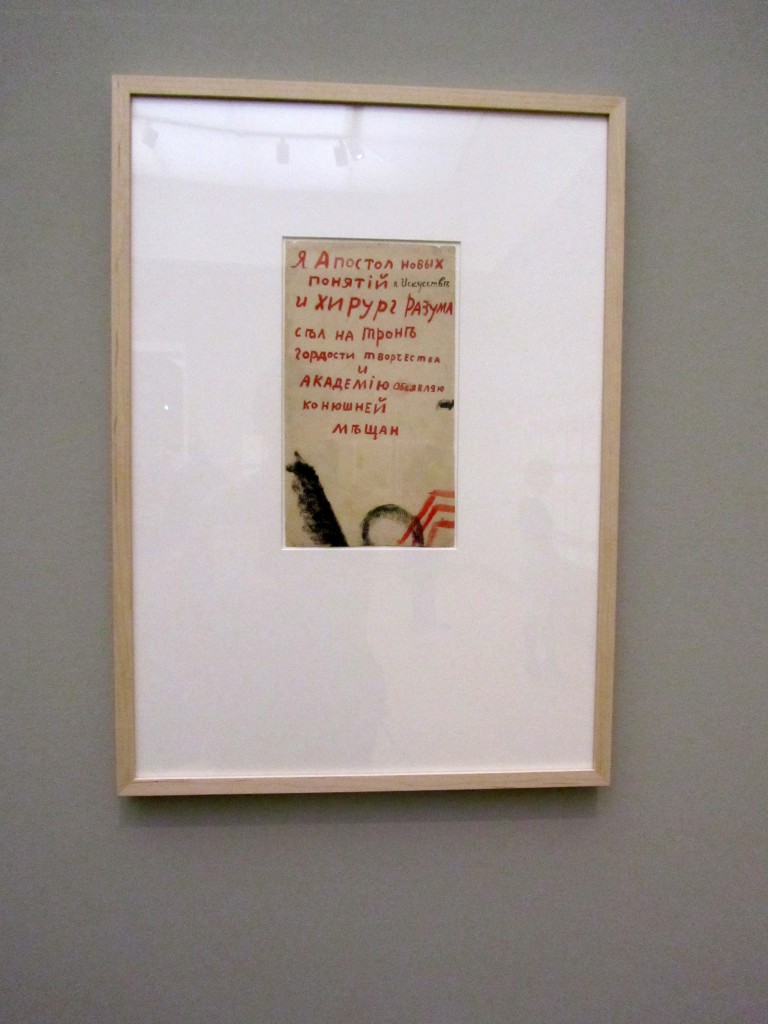

‘I, the apostle of new concepts in art and surgeon of the spirit, have taken up residence upon the proud throne of creativity and I declare the academy a bourgeois mass.’

Malevich appointed himself as an apostle and an exponent of the art of cosmic harmony. A true artist-philosopher, he proclaimed a doctrine that was designed to inspire the human spirit.

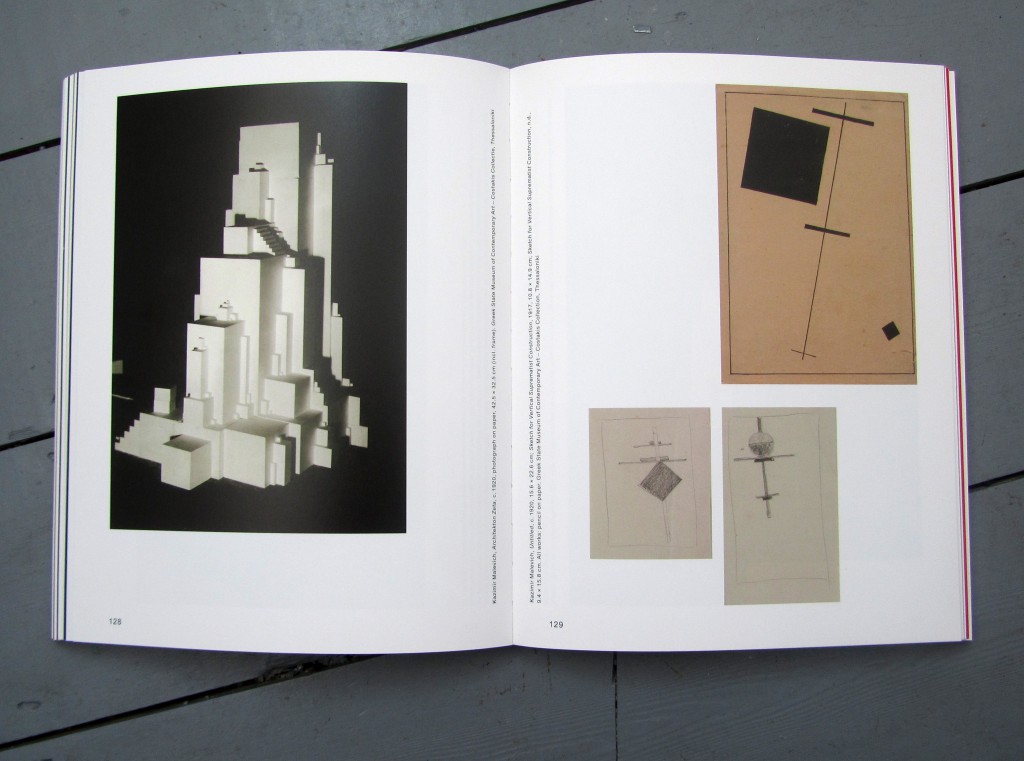

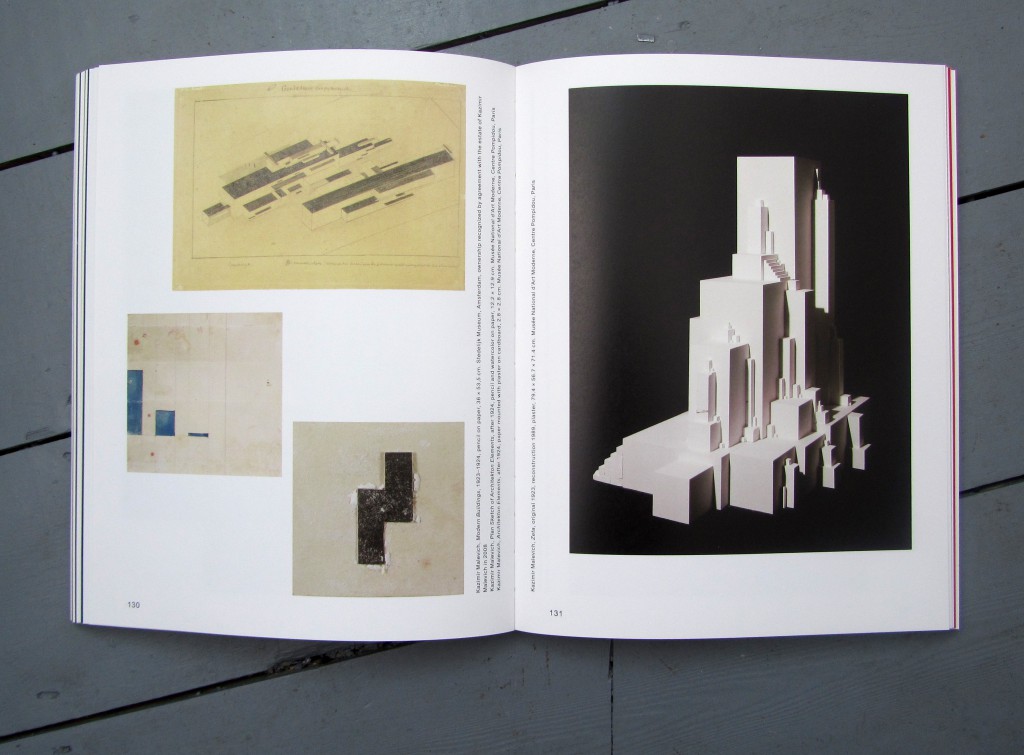

Left: Architekton Zeta, c.1920, photograph on paper, Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art – Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Right: Zeta, original 1923, reconstruction 1989, plaster, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris.

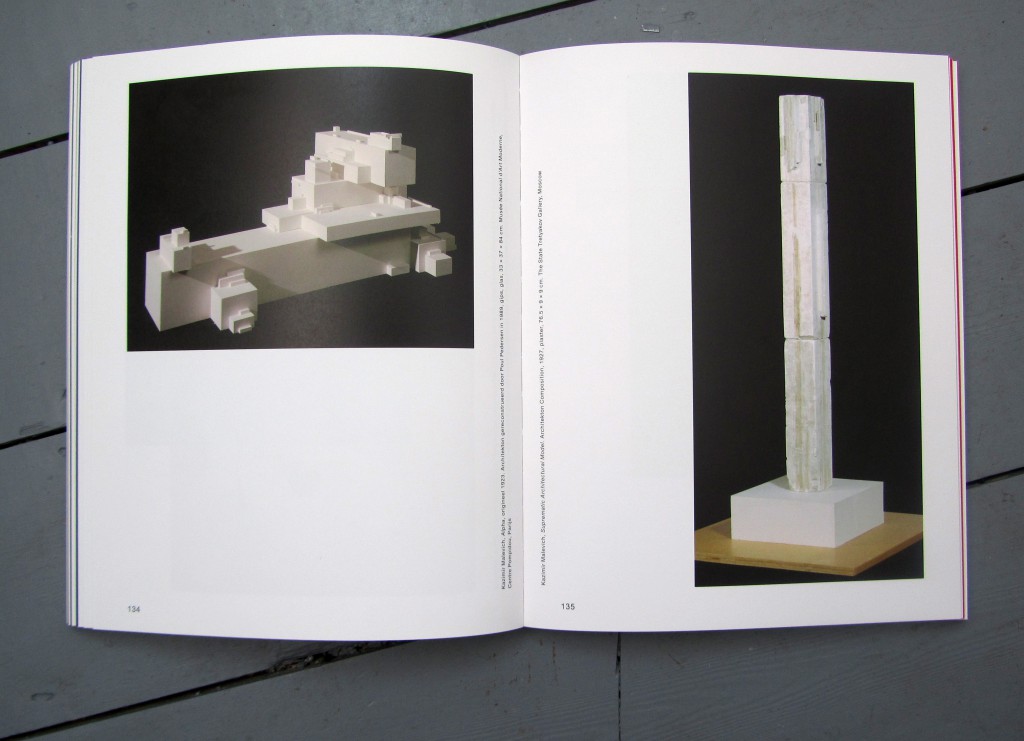

Left: Alpha, original 1923, reconstruction 1989, plaster, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Right: Suprematic Architectural Model, Architekton Composition, 1927, plaster, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

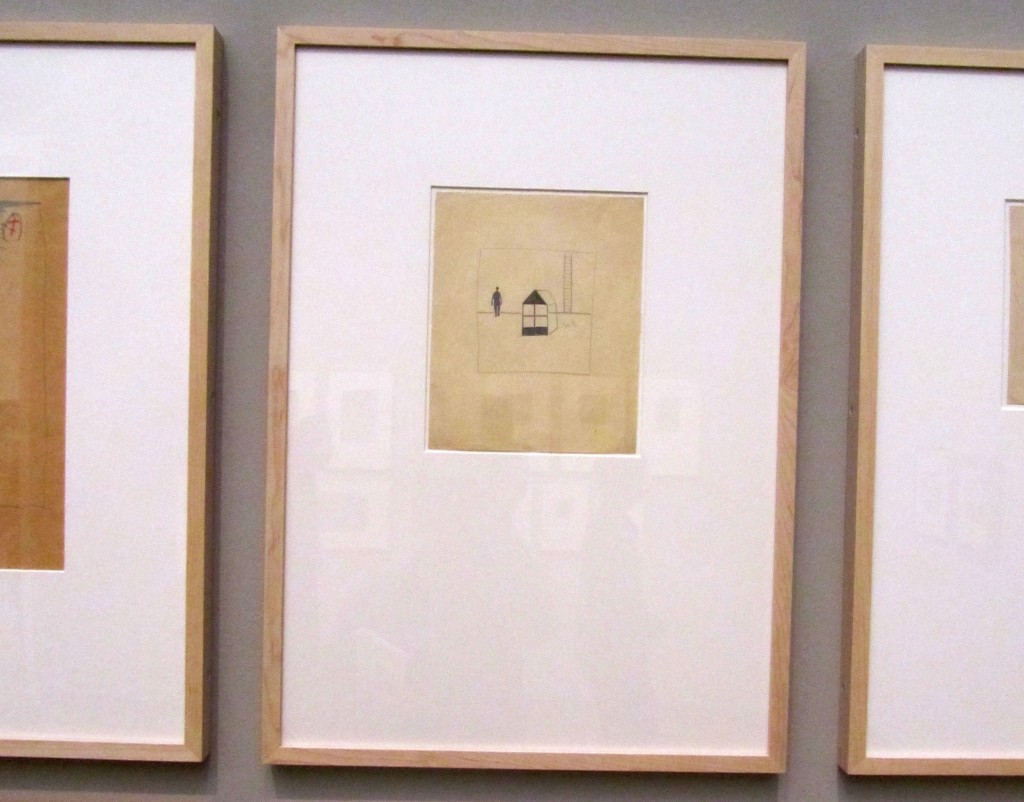

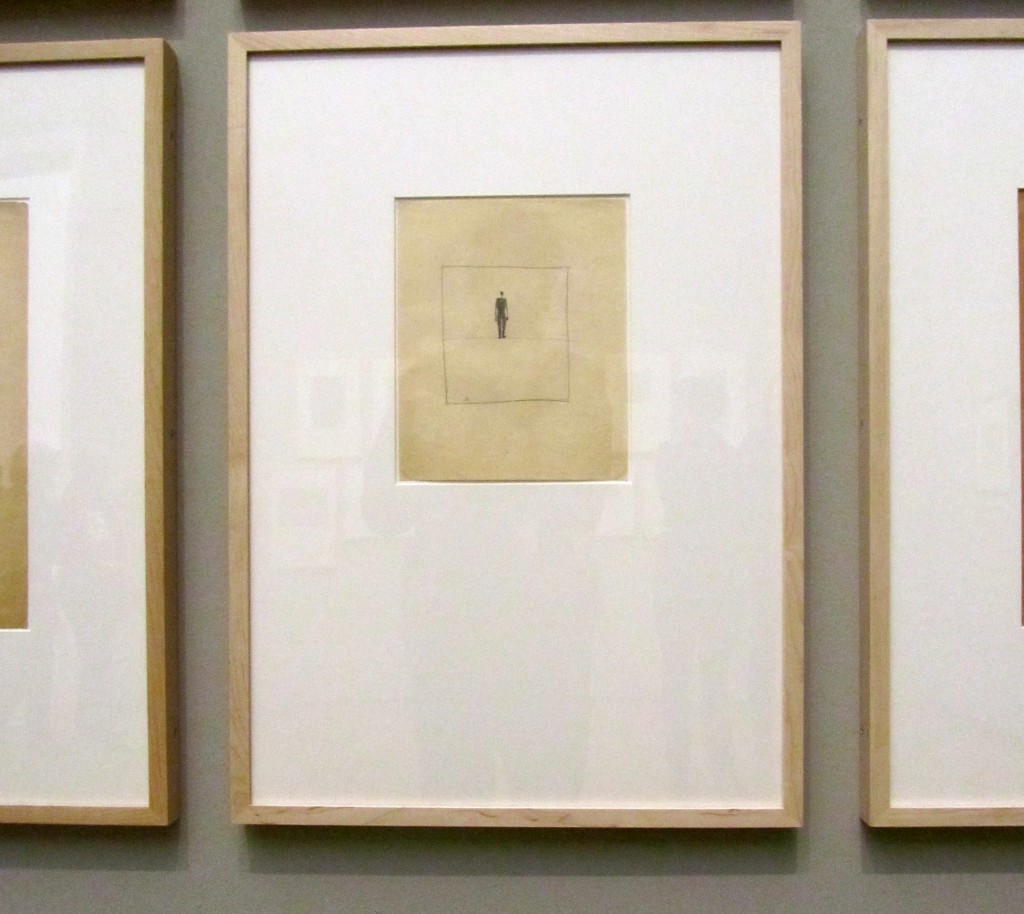

Segodnyashnye Sooruzheniya, 1923-24, Modern Buildings, pencil on paper, Stedelijk Museum.

Malevich’s designs for Planits – architectural constructions that would support human life beyond planet Earth – parallel the writings of philosopher Nikolai Fedorov. According to Fedorov, humans, assisted by technology, would eventually have the ability to complete “the project of God” and bypass death to achieve a state of immortality. This new human would subsequently use scientific knowledge to resurrect previous generations and would spread out across the universe as Earth becomes too crowded. The Planits are simpler in design than the Architektons and are not earthbound. They are three-dimensional constructions that may be likened to spaceships or extraterrestrial houses.

Steps (Project for Suprematist Décor of the Red Theatre, Leningrad), 1931, watercolour on paper, Annely Juda Fine Art, London.

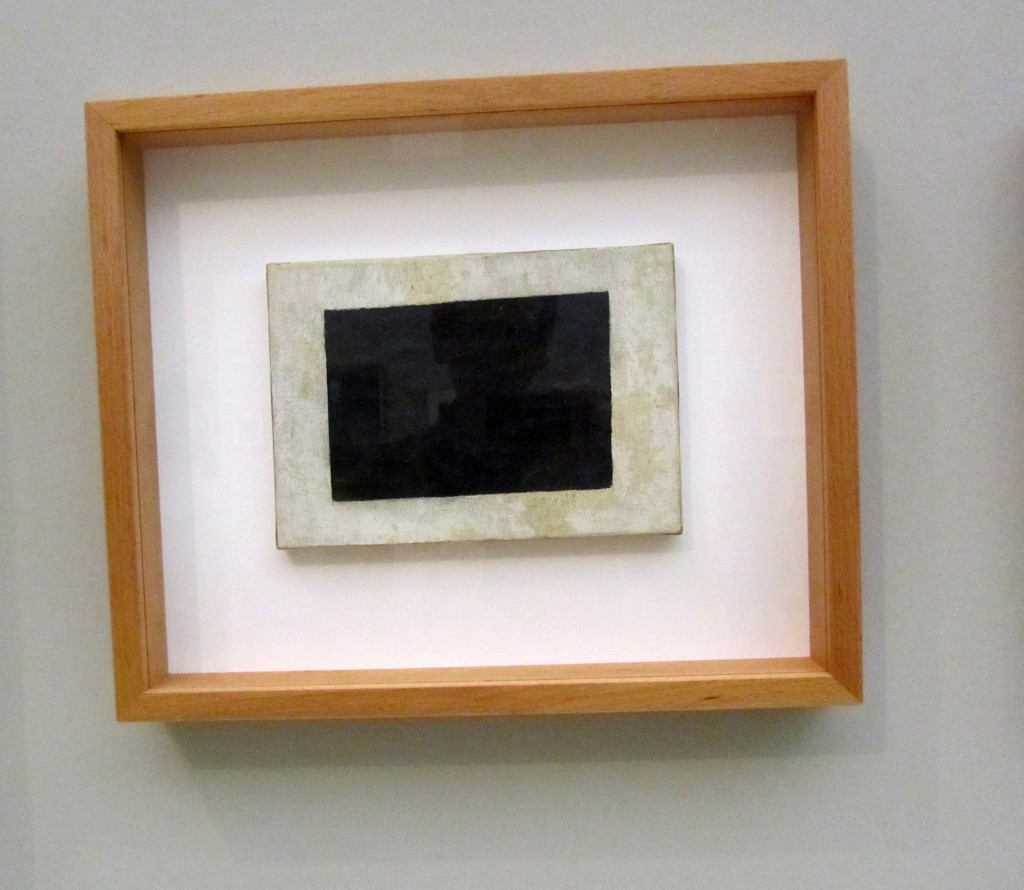

Black Quadrilateral, not dated, oil on canvas, Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art – Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich was born… on 23 February 1879 in Kiev. While attending agricultural school, the young Malevich devoted an increasing amount of time to painting, until the mid 1890s when he dedicated himself exclusively to art. An autodidact up to that point, he felt an intensifying need for academic training, which prompted his decision to move to Moscow in 1905. There, he started exhibiting his works and became acquainted with members of Moscow’s avant-garde… In July 1913, Malevich conceived… a Futurist opera, ‘Victory over the Sun’… staged that December in Saint Petersburg. In 1915, Malevich exhibited his first Suprematist paintings in the now legendary exhibition ‘0,10’.

…In 1924, he was appointed director of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (GINKhUK), where he led the Department of Painterly Culture… It was at the institute that he resolved his ideas for a Suprematist architecture in a series of models, which he called ‘architektons’. In the spring of 1926, however, he was dismissed as director of GINKhUK.

In 1927, in preparation for a trip to Berlin and Warsaw, Malevich designed a series of explanatory cards to function as visual aids for lectures. On 8 March, he traveled to Warsaw and later that month to Germany, where he visited the Bauhaus in Dessau. Before his departure from Germany on 5 June, he entrusted the works he brought with him to architect Hugh Häring.

After returning to Leningrad, Malevich published several articles, but his views were no longer appreciated in the Soviet Union, resulting in his expulsion from the State Institute for History. Even so, a retrospective exhibition of his works opened at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in November 1929. In 1930, however, the government’s pressure on Malevich mounted, and he was held for some time for questioning. As a precautionary measure, friends burned a large number of his manuscripts. Malevich recommenced figurative painting, which he had abandoned so long ago. These later works were featured in several exhibitions during the early 1930s.

Girl with a Red Pole, 1932-33, oil on canvas, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

In the late 1920s, abstract art, which had previously flourished in Russia, was banned by the Soviet regime. Artists were required to conform to the propagandistic art of Social Realism. Malevich returned – possibly under duress – to figuration. He began a series of portraits based on Russian folk art and icons, themes that also had featured in his early work. Malevich did, however, remain true to his Suprematist use of form. ‘Girl with a Red Pole’ is an early example of this imposed approach. The face and hands of the peasant girl are depicted realistically, but they contrast with her clothing, which is made up of flat and abstracted forms. Only her torso suggests volume. The composition is reminiscent of earlier compositions created during Malevich’s heyday, in which geometric forms float in white spaces. The serene and sublime atmosphere emanating from this tranquil portrait almost has the religious aura of an icon.

Girl with a Comb in Her Hair, 1932, oil on canvas, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, 1933, oil on canvas, Moscow Museum of Modern Art.

Ivan Klyun, Malevich on his Deathbed, 15 & 16 May 1935, Khardzhiev Foundation.

The artist, Ivan Klyun drew several renderings of his old friend and mentor during Malevich’s final days and shortly following his death. In his memoirs, Klyun described the ailing Malevich as embodying the dying Christ as depicted by the Renaissance artists. Klyun probably made this drawing on the day after Malevich’s death. A second drawing shows the artist sunken into his pillows, his head at an angle and his hair tousled, at the moment of death or soon after. Although Klyun had turned away from Suprematism in 1919 and his relationship with his teacher cooled as a result, Malevich’s final wish was that Klyun should be present at his deathbed. Malevich died of cancer on May 15, 1935. In a tribute to his deceased mentor, Klyun wrote: “Malevich was my best and closest friend.”

※

Excerpts from the exhibition catalogue, Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde, are courtesy of Linda S. Boersma and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

This exhibition will open at Tate Modern on July 16 – Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art.

I really appreciate the time you take to put together these great posts.

Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Bill, nice of you to say so.

Hi, Thank you for sharing . I do wish to study more on this artist and his works on geometrical abstractions. Can u suggest a good source.