Further on down the road we came to Gamlingay, a familiar sounding place, its pretty name once heard and hard to forget. We got lunch at the Cock Inn while villagers hung out flags for St George. And I remembered that the church of St Mary is renowned for its medieval graffiti.

Graffiti (‘drawings or writings scratched on a wall or other surface’) are to be found incised on the walls and pillars of innumerable cathedrals and churches in Great Britain. Most were done between the twelfth and early fifteenth centuries; many are valuable as examples of medieval art; and some are important for their preservation of particular styles of epigraphy.

In this pioneer work, Mrs Pritchard has studied the inscriptions and drawings in a large number of churches, mostly within a radius of sixty miles of Cambridge. These graffiti are far from mere scratchings performed by unskilled hands; they are imaginative, boldly executed drawings, combining freedom of line with occasional fussiness of detail, and inscriptions whose clarity and precision of lettering equal in execution the contemporary manuscript. Many were subsequently covered by medieval wall paintings; others have been partly defaced by cleaning and restoration of the original stone.

Mrs Pritchard illuminates a neglected corner of medieval art; and her skilful rubbings (over two hundred of them illustrate this book) preserve these curious relics of medieval artistry against the erosion of time and restoration.

I’d found this book years ago in my favourite bookshop, Notting Hill Books, and I particularly remembered this drawing. It had inspired me to try my hand at similar inscriptions of my own.

The small crowned head (fig. 50) is perhaps one of the most beautifully drawn graffiti in this collection, and is comparable with miniatures in manuscripts of the same period. Sir James Laver is of the opinion that the date of the drawing is between 1400 and 1410. It is on a pillar in the south arcade only a few inches from the floor; but it is not likely to have been drawn there originally.

Another head greeted us in the church porch,

and behind the door a metal hook had worn its own smile into the wall.

The stone pillars are rich in graffiti, with a variety of motifs often hard to decipher, each entangled with the next. Sometimes faces becoming ships becoming shields becoming more and more abstract.

Constellations of masons marks.

Runes and hieroglyphs and billets-doux.

Look here closely, two faces hidden in the undergrowth.

And there she was, the beautiful crowned head of Gamlingay.

A picture arrests time and brings to life a lost moment in a century long past.

Then two compass flowers and two more heads.

On the base of the same pillar but on another face there is a palimpsest (fig. 51). The heads were almost certainly drawn first and the ornamental circles subsequently. The unusual head-dresses are remarkable in their resemblance to those on Roman coins.

Click on this photo and zoom in to discern two more portraits.

Two more heads (fig. 52), of quite different character, are on a pillar in the south arcade, about four feet from the ground. If these heads have been drawn by the same hand, as they appear to be, then the draped liripipium, which forms the hat worn by the second man, is evidence that the graffito is not earlier than the end of the fourteenth century. There is enough character in the faces of these men, especially in the first one, to suggest that they were drawn from life.

See here, bottom left, another beautiful portrait.

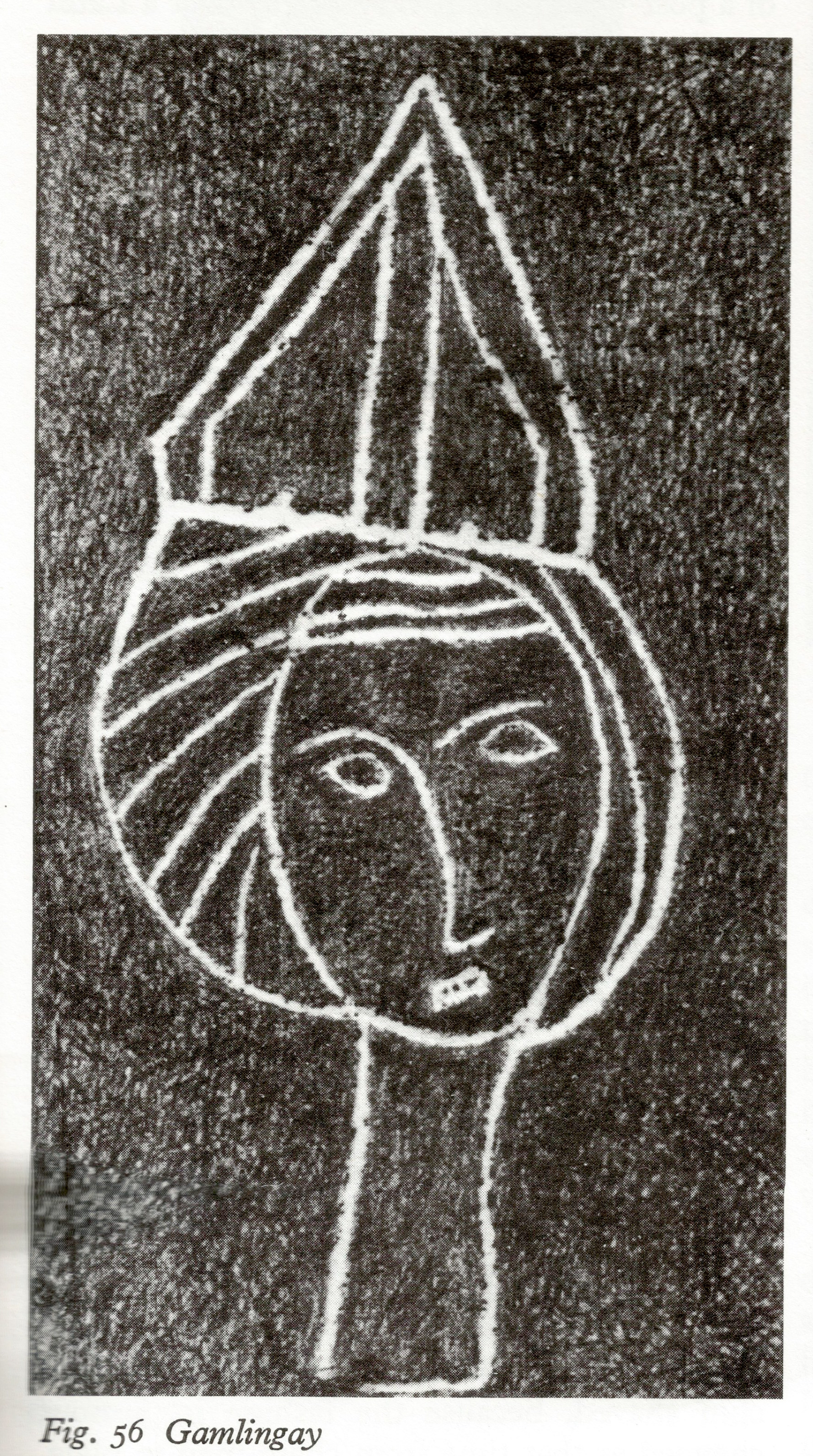

A mitred head (fig. 56) is drawn on a pillar in the south arcade. It is somewhat surprising to find a mitre on what appears to be the head of a woman.

Mors co[m]parat[ur] umbre que semper sequitur corpus

(Death is like a shadow which always follows the body)

※

English Medieval Graffiti by Violet Pritchard,

first published by Cambridge University Press in 1967, republished in 2008.

Fantastic.

fabulous revealings on busy walls