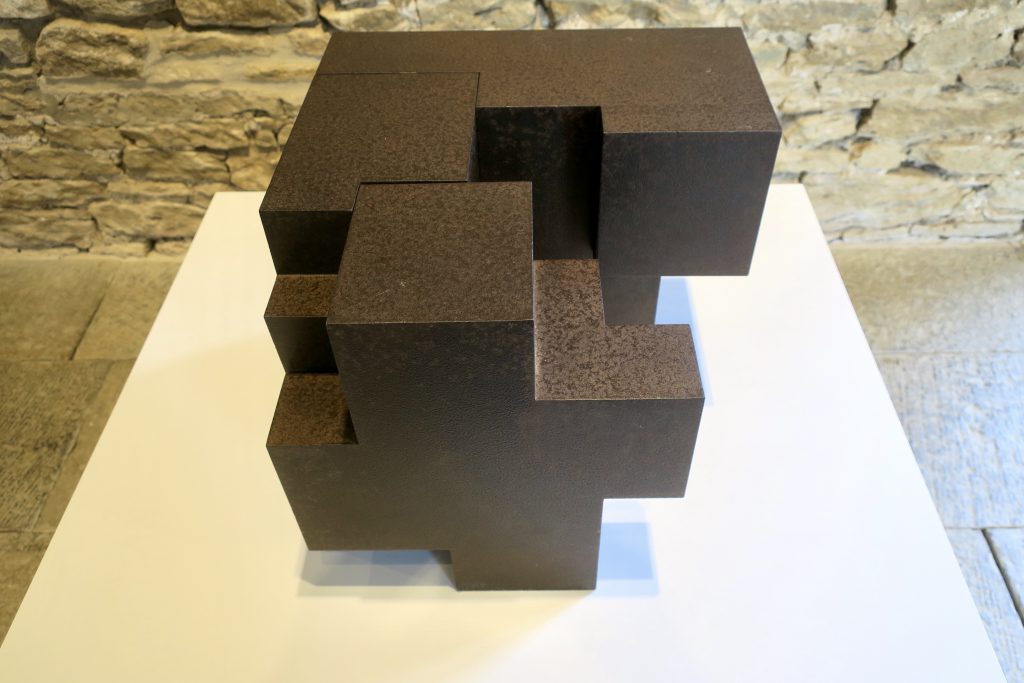

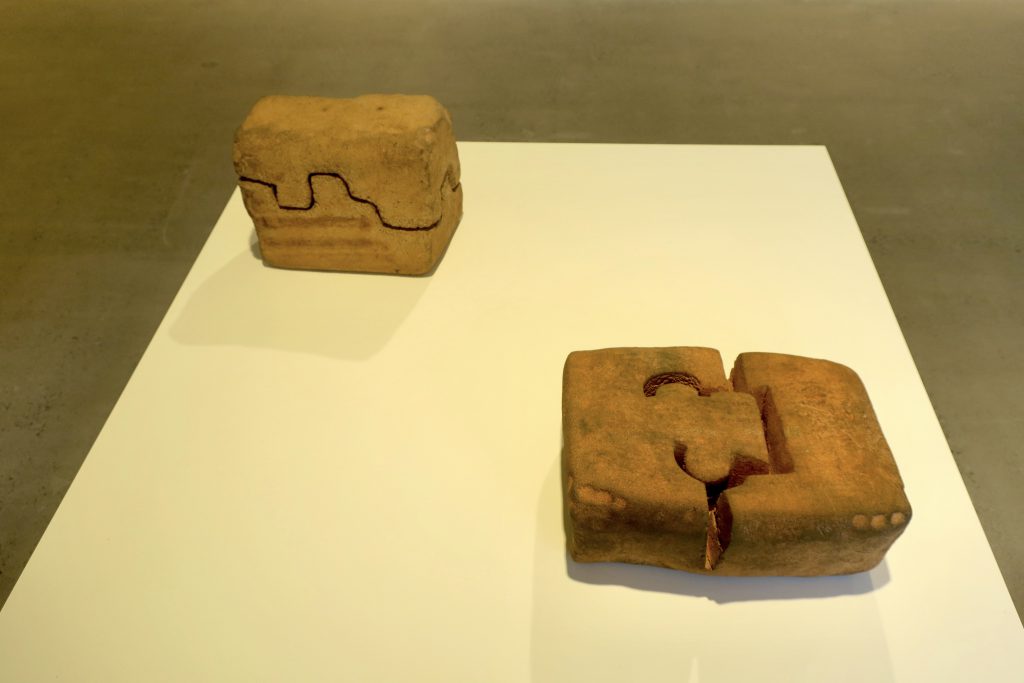

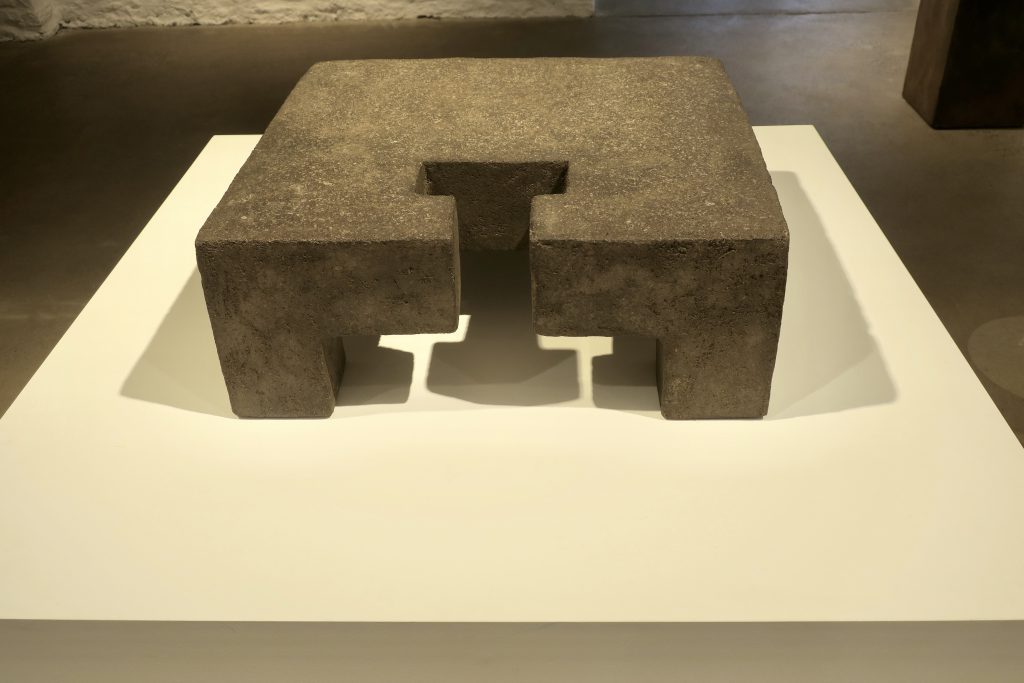

This was the first sight. Ignore the car park and the fancy farm shop and the reserved restaurant and the souvenir bookshop. Outside on the grass, just as the rain began to fall, my eyes met Harri VI (it translates as Stone VI), a great carved block of granite. Imagine that. How is that possible? The equivalent of a giant fist carved in granite. A fistful of granite. I love it.

We were at Durslade Farm in Bruton, the gallery of Hauser & Wirth Somerset. We’d long ago visited Chillida Leku in the Basque region of northern Spain, the most beautiful Chillida museum. It subsequently fell on hard times but it was recently reopened with support from Hauser & Wirth. This time round we were on our way back to London from Dorset. Northern Spain was out of the question but Bruton was within reach. It was our first exhibition in two years, we were masked spectators, art in the time of Covid.

It was a great joyful eyeful of an exhibition. Like meeting an old friend, familiar and surprising. I recorded it all with my quick click-happy camera.

The first great exhibition of Chillida sculpture in the UK was at the Hayward Gallery in 1990. Ironically I’d worked there briefly in the early 1980s but totally missed this one. I wasn’t aware of Eduardo Chillida until I saw an exhibition at the Annely Juda Gallery in 1992. How had he passed me by?

“His work is to be found in the great museums and collections of Europe and North America: he is commissioned to work on the largest possible scale: and he has been winning prizes and honorifics since the Triennale de Milano of 1954, that include the Gran Premio di Scultura at Venice in 1958, and the Carnegie Prize at Pittsburg in 1964. Of these, most distinguished of all, perhaps, was the Omaggio paid him by the Venice Biennale of 1990, in a special retrospective exhibition.

“Yet here in Britain we would hardly know it. All credit to the Royal Academy for having the independent judgement and open-heartedness to make him an Honorary Academician in 1983, for at that time his record here amounted to a single solo show, at McRoberts & Tunnard in 1965, and a meagre handful of group exhibitions spread thinly over the years. The Tate has a single work, seldom shown, bought in 1965. But for the South Bank Centre’s splendid retrospective, that filled the Hayward in the autumn of 1990, as physically beautiful a display of sculpture as any in that gallery’s distinguished history, and as sparsely noticed, and a single show with Anne Berthoud in 1985, we could hardly say that our dismal record has improved. It is still hard to believe that this is to be but the fourth Chillida solo show in London over a career that now stretches to nearer fifty than forty years. It is, I need hardly say, all the more welcome for that.”

William Packer, catalogue essay, Edouardo Chillida, Sculpture & Works on Paper at Annely Juda Fine Art, 1992.

And this too, almost 30 years later, is another rare and welcome exhibition.

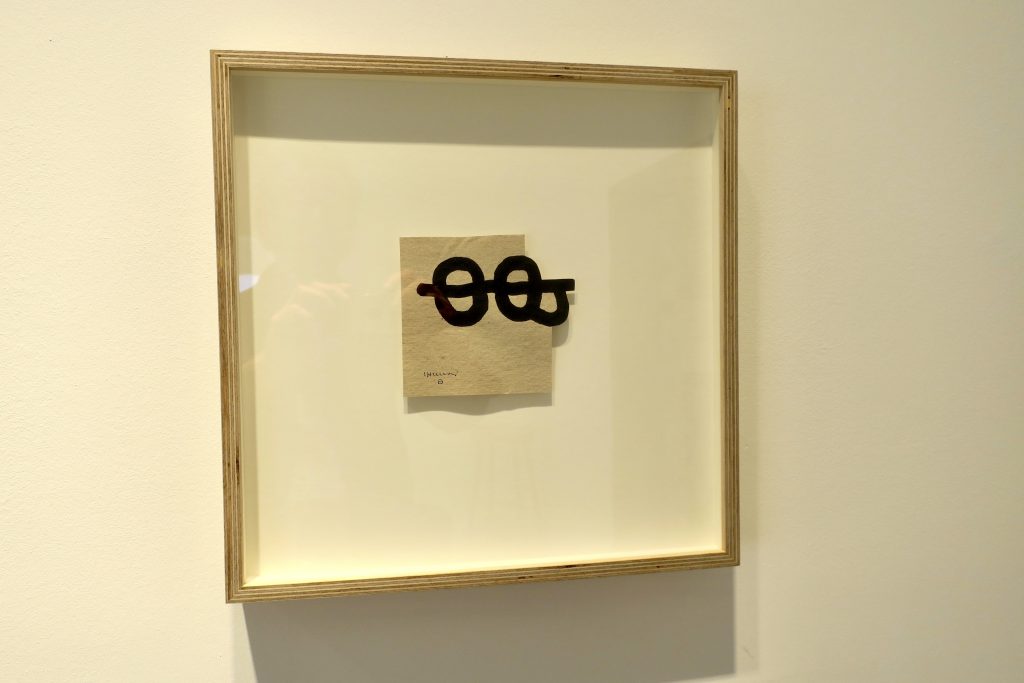

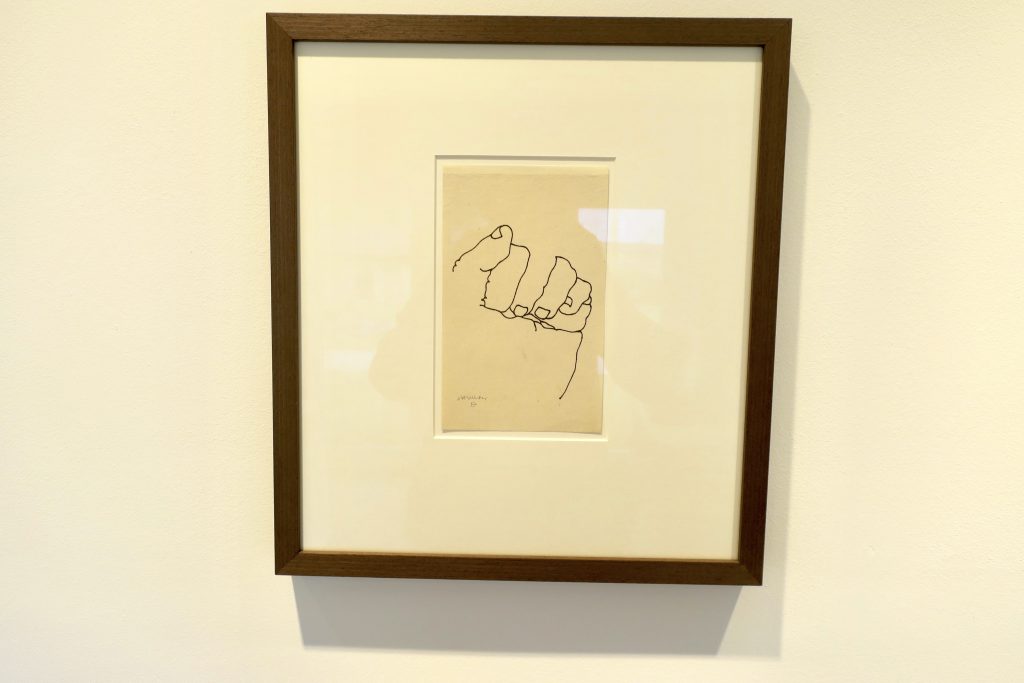

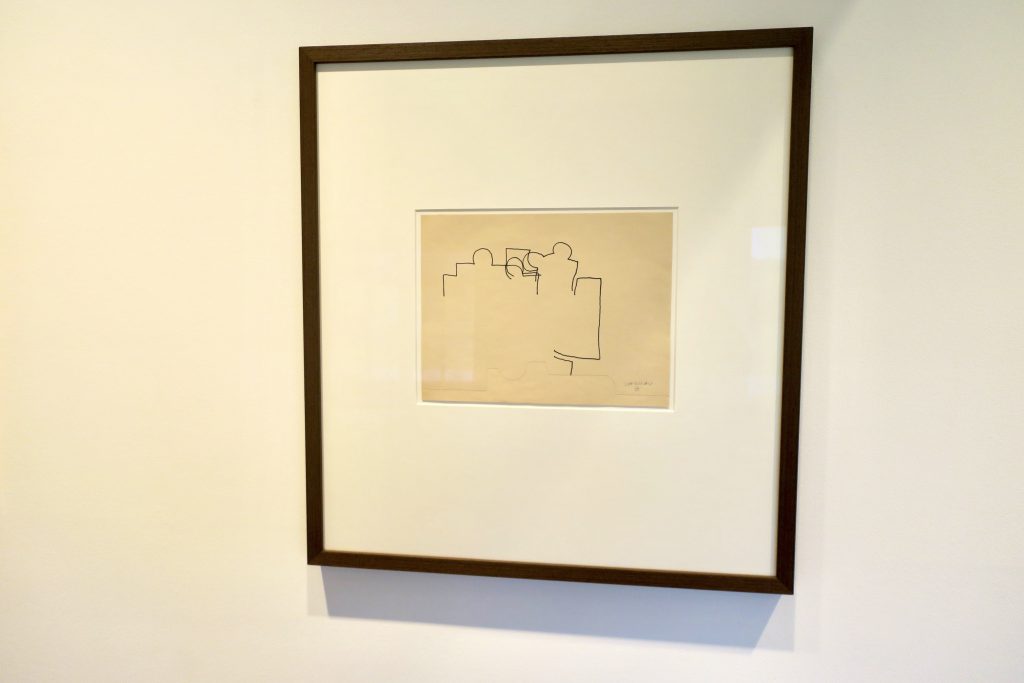

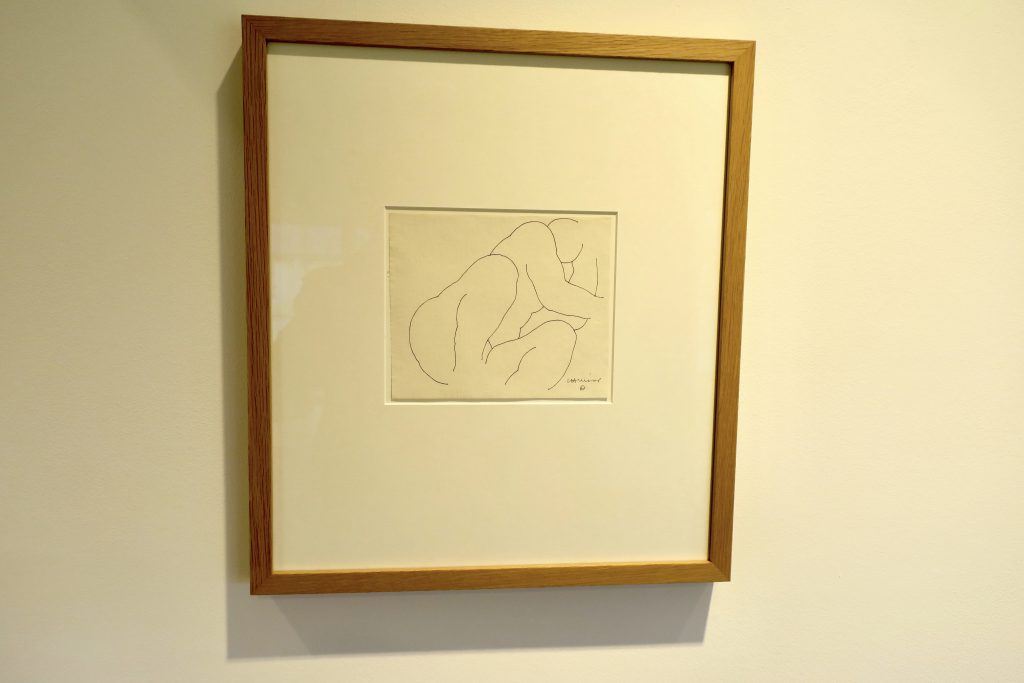

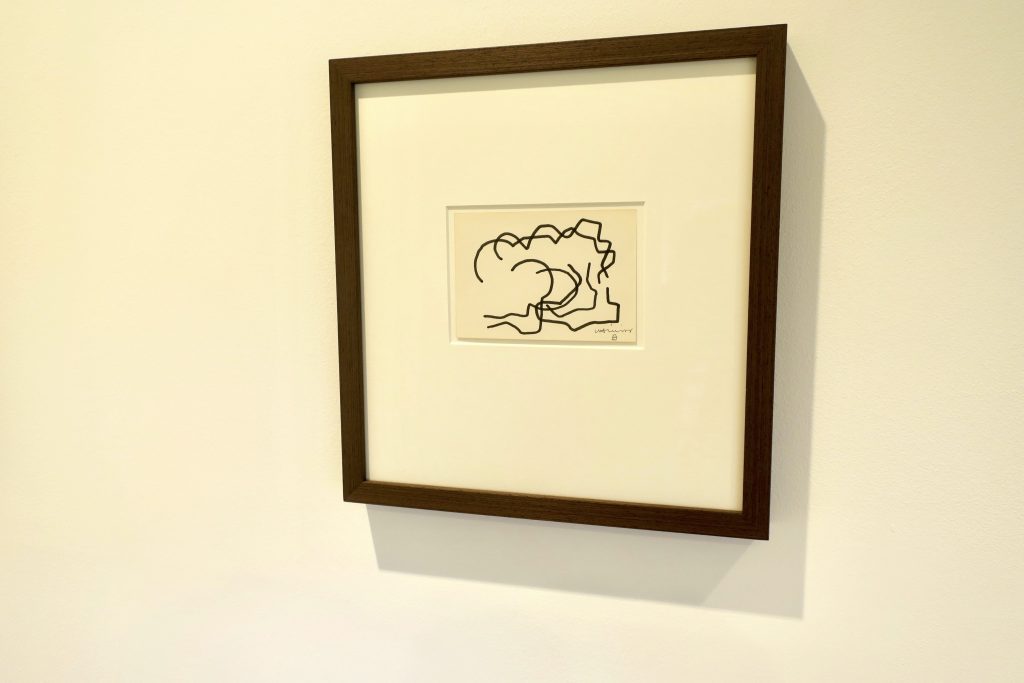

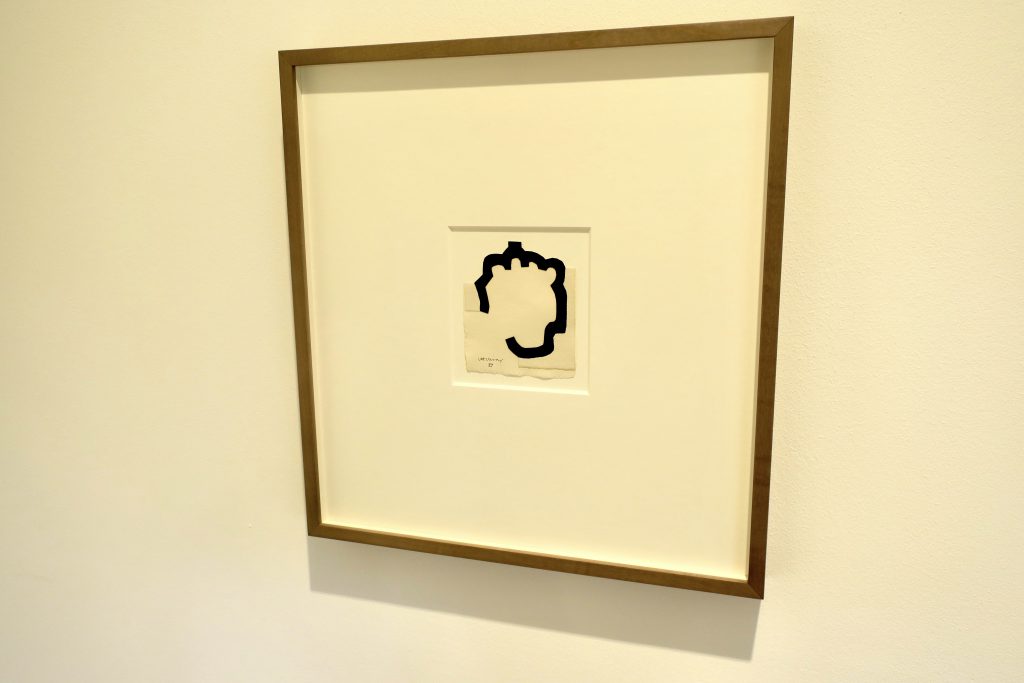

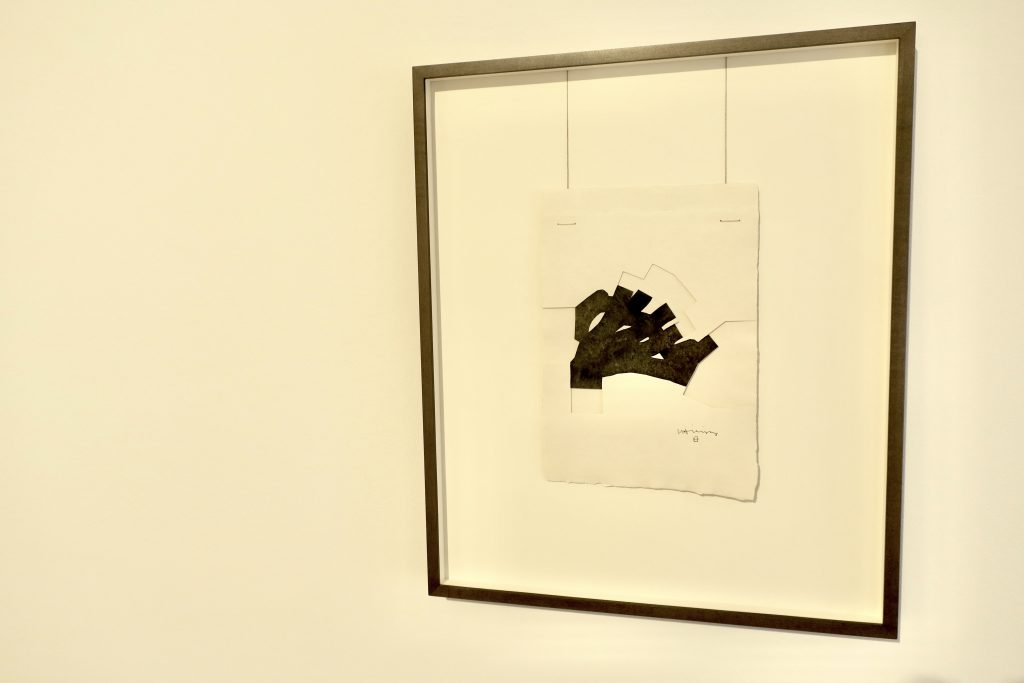

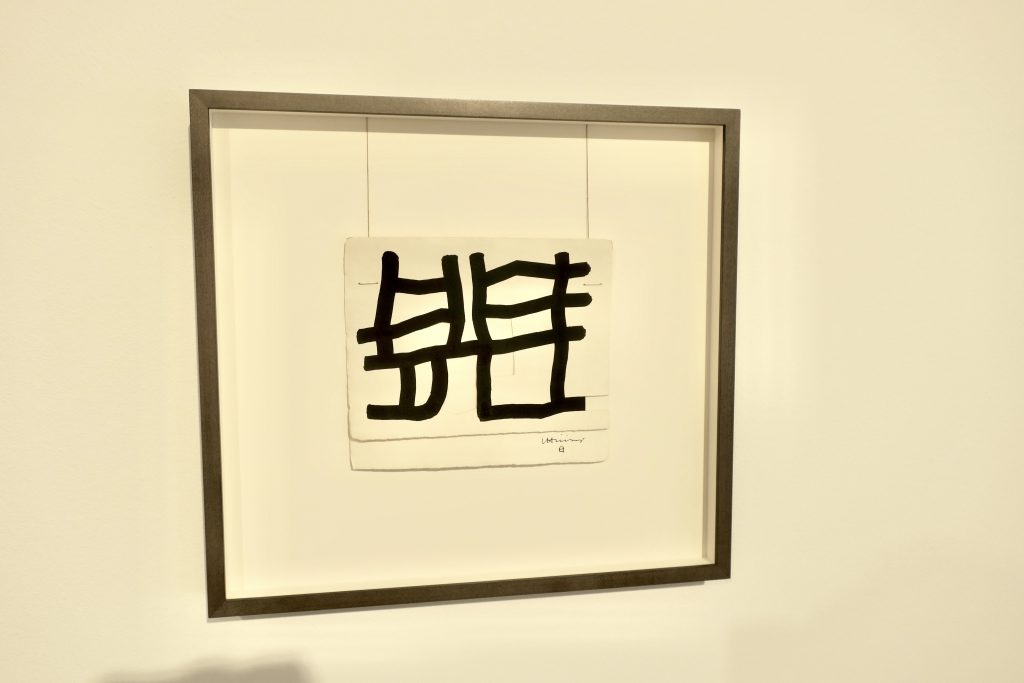

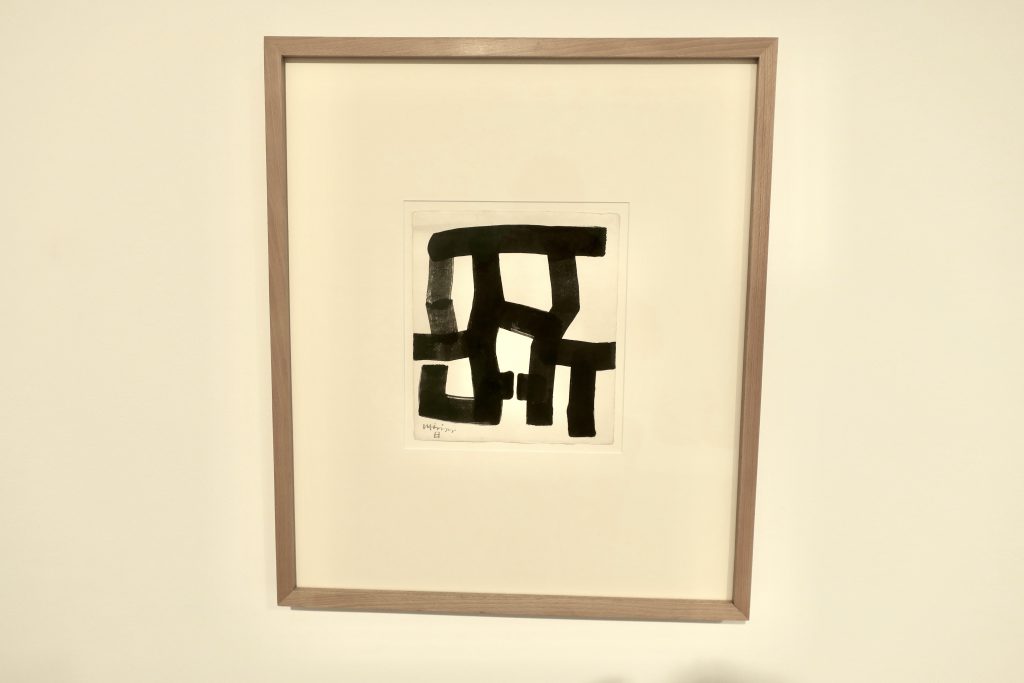

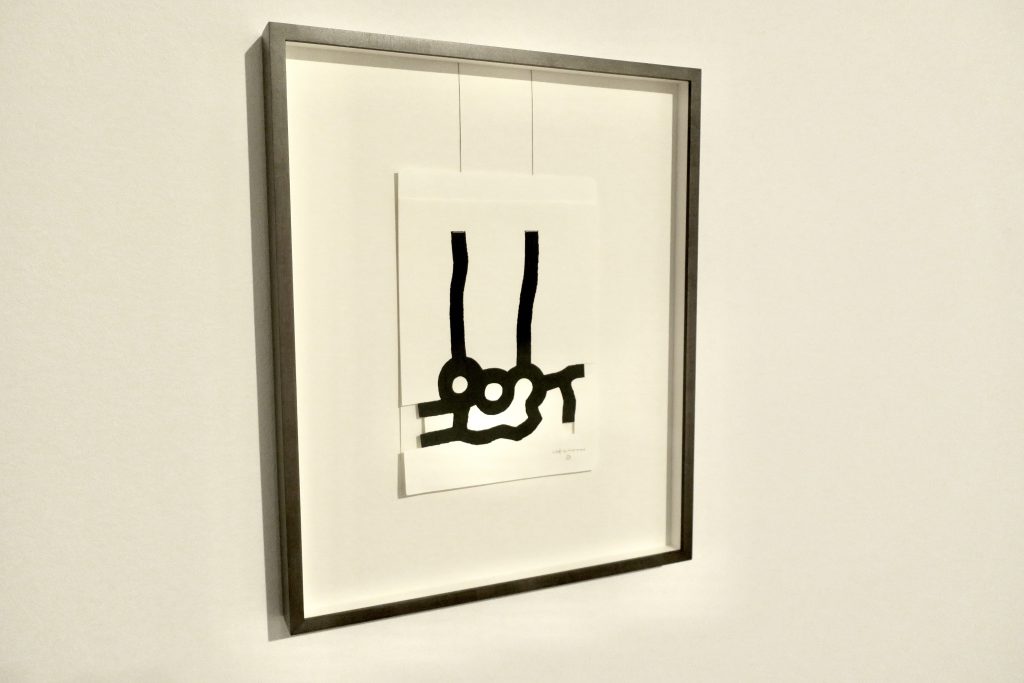

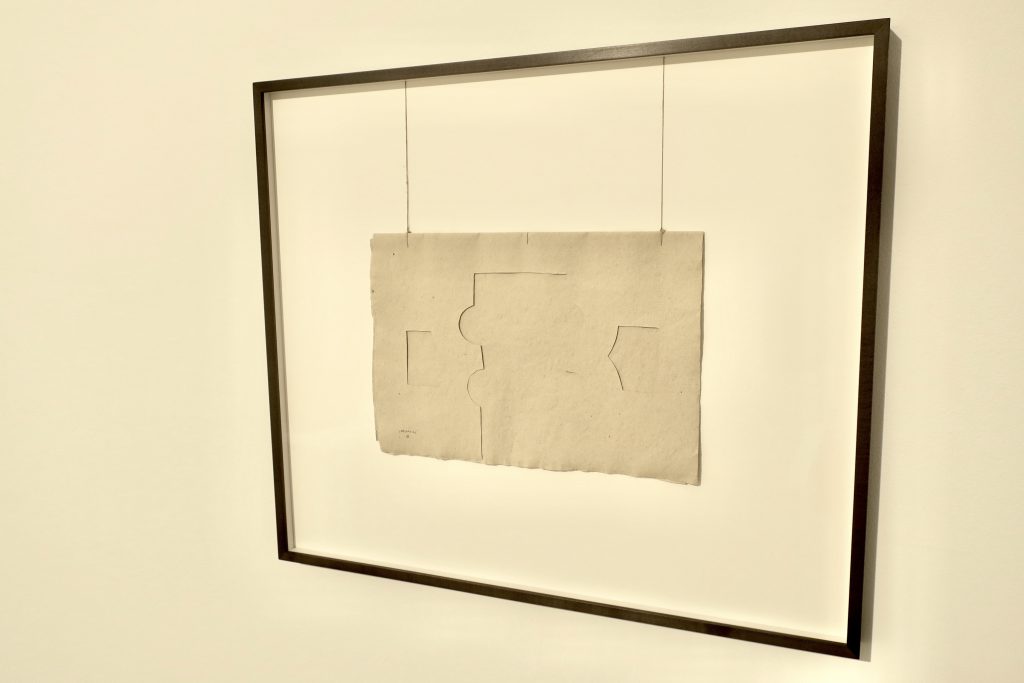

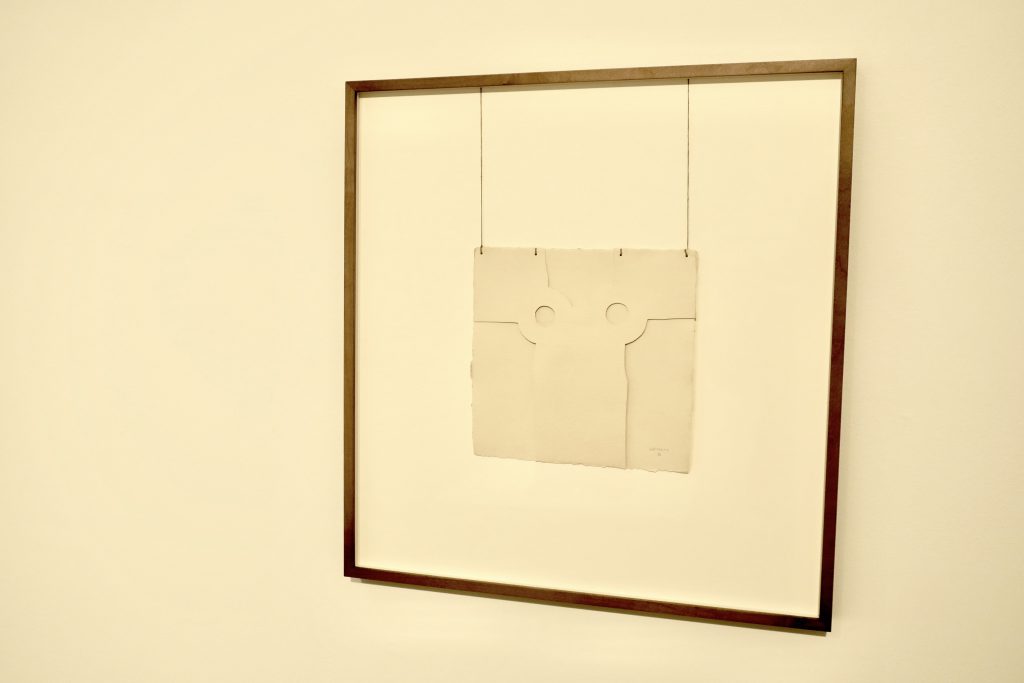

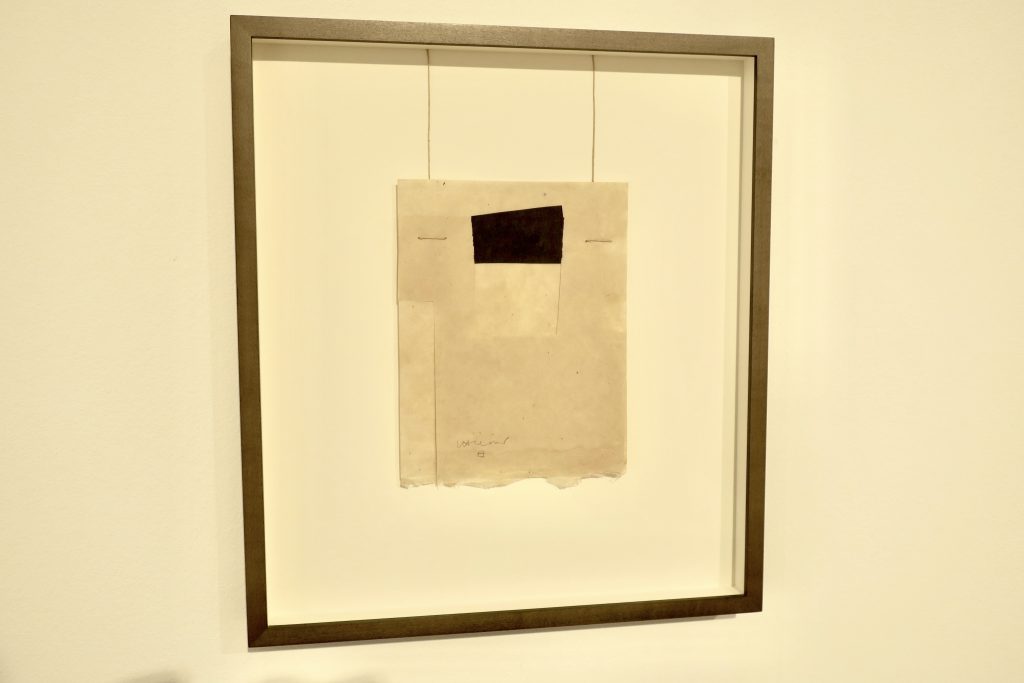

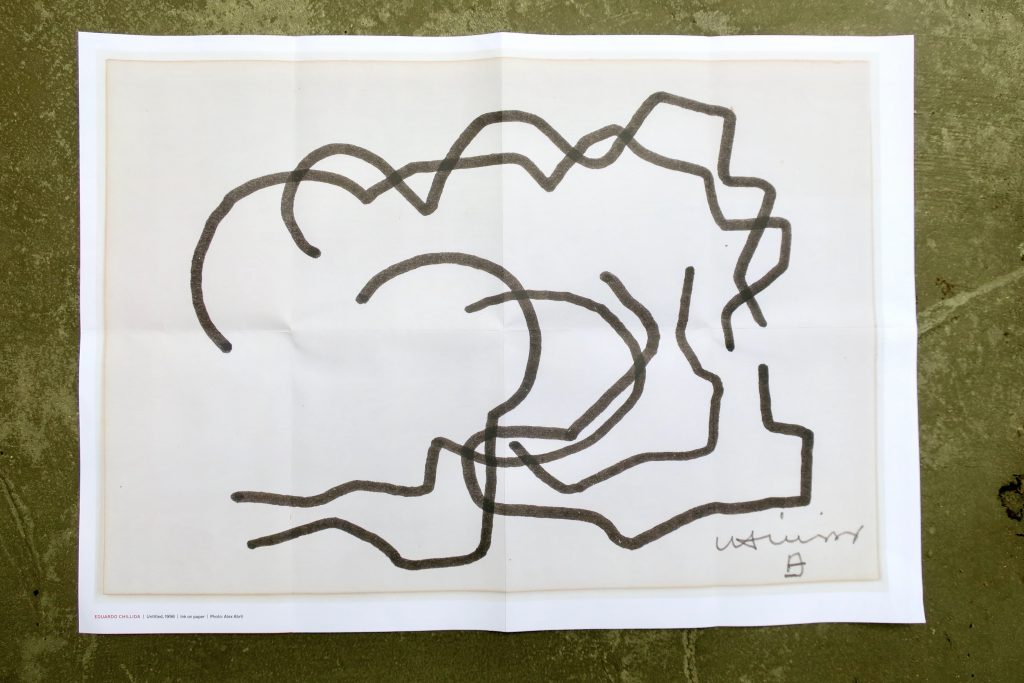

What I’d loved most at that first sight were his ink drawings on bark paper, intimate and intricate constructions, sometimes hung on strings, they also reminded me of Richard Smith’s kite paintings, and they inspired me to try drawing on bark paper for myself, though never quite with his fluency.

Over the years I’ve come to love his sculptures too. I’ve looked out for them wherever I’ve been. Type the word Chillida into the search engine at the top of this page for all the other blogposts where he’s made an appearance.

Large or small, his sculptures are all wrought by hand, they display his handiwork, even on a grand scale when other hands have helped him, they are still manipulated with his strength and dexterity and grace.

He is, like (Henry) Moore, a carver and a modeller, cutting, twisting and forging the particular intractable material to his own ends. He is never the assembler, the welder or collagiste of given elements, for all that so often his work could only be accomplished, bent or cut, by the heaviest industrial machinery. The sense is always of the object made, whatever the literal truth of it, directly under the artist’s own hand. And given this quality of physical engagement, the sense returns of the human scale and physical presence, unspoken and unspecific, but real enough. The carvings offer spaces to enter and inhabit in the imagination; the writhing metal arms and fingers invite a true embrace, if only of the wind…

William Packer, Ibid, 1992

A Bach piano soundtrack accompanied us around the exhibition, so that our ears as well as our eyes were able to tie all the pieces together. I would have happily gone around again and again until the music stopped, but after only a few more photos the battery in my camera expired, so it was time to leave.

“I’m of the opinion that we should all be from somewhere… Our roots are buried in one place but our arms reach out to the entire world, and the ideas from any culture should be of value to us. Here in the Basque Country I feel like I’m where I belong, like a tree adapted to its environment, whose branches stretch out to the rest of the world…”

Eduardo Chillida

※

Hauser & Wirth / Eduardo Chillida

Thank you for this. Saw a show of his at the Bilbao Gehry gallery about 15 years ago and loved it. Hope to get to this one

Just returned home from the Hauser and Wirth Gallery in NYC. No Chillida sculpture but lots of Phillip Guston (with Gilbert and George next door).

This looks like a ‘must visit’ thanks so much for the private view. So simple and strong, and poetic too!

I love it, isobel