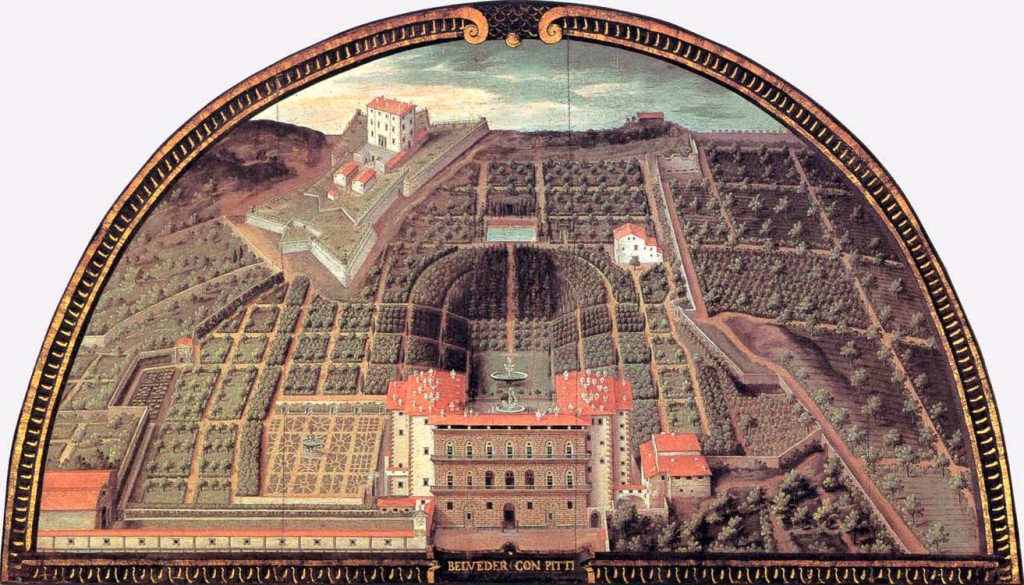

Palazzo Pitti & Forte Belvedere, one of a series of paintings of Medici villas by the Flemish artist Giusto Utens from 1599. The fort was built nine years earlier, on the highest hill of the Boboli Gardens to protect and watch over and keep an eagle-eye on the city of Florence down below.

In recent times Forte di Belvedere has become a site for art exhibitions, opening in 1972 with a display of works by Henry Moore, a renowned exhibition which has become a part of the history of Florence.

La retrospettiva di Henry Moore al Forte di Belvedere, Firenze

A groovy film with a psychedelic soundtrack that sounds like it might have been recorded underwater.

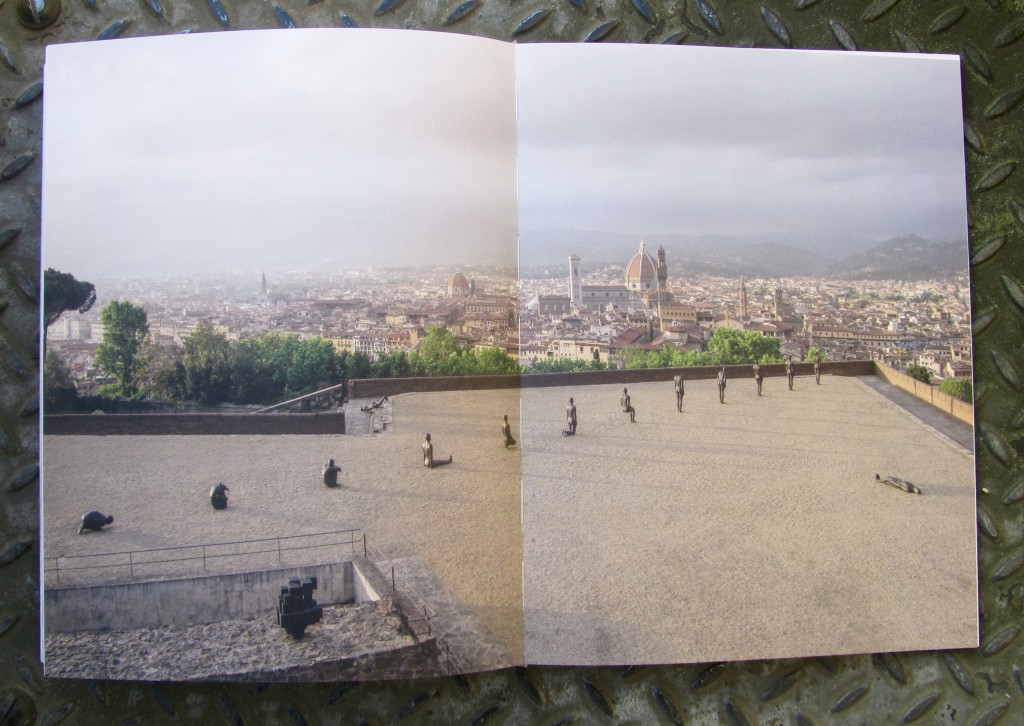

There is indeed nowhere better in the world to display sculpture in the open air in relation to architecture and a city than the Forte di Belvedere, with its imposing surroundings and marvellous views of Florence.

Henry Moore 1972

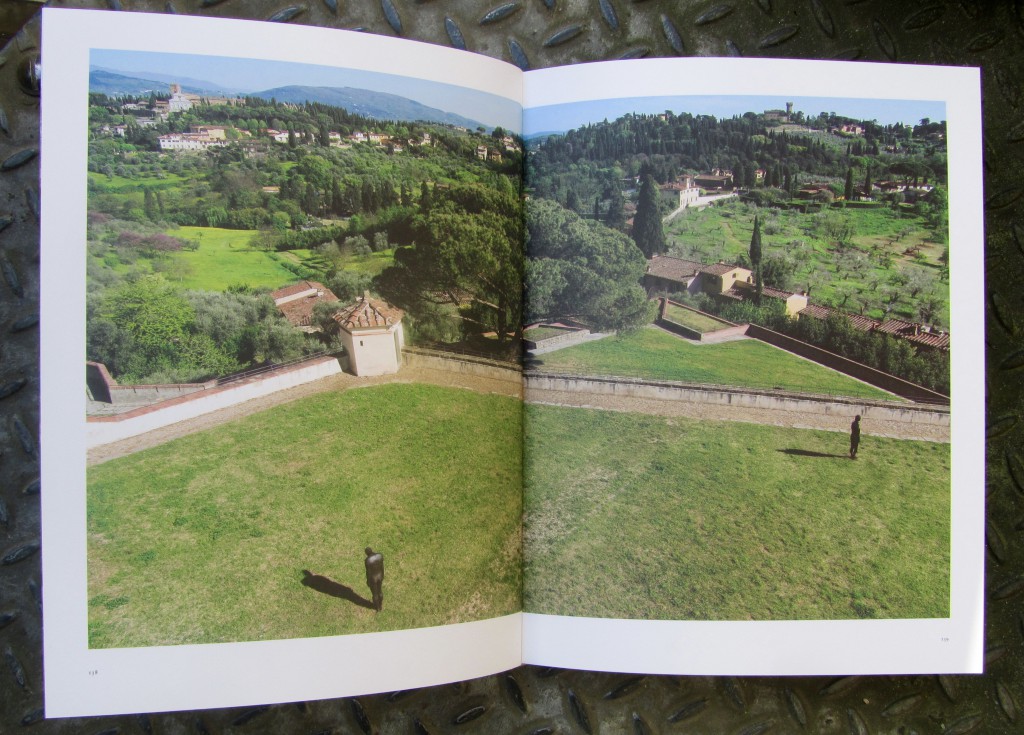

Then last year we kept seeing posters around Florence for an Antony Gormley exhibition. They led us via the Pitti Palace and the Boboli Gardens to the Forte di Belvedere. It was an unexpected bonus.

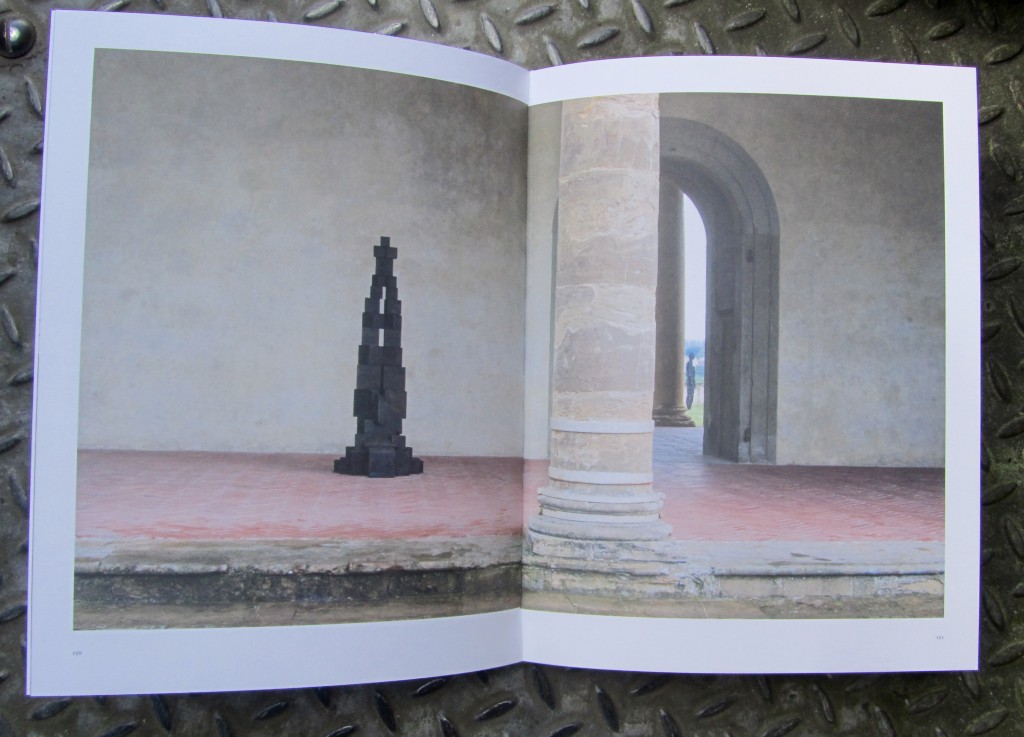

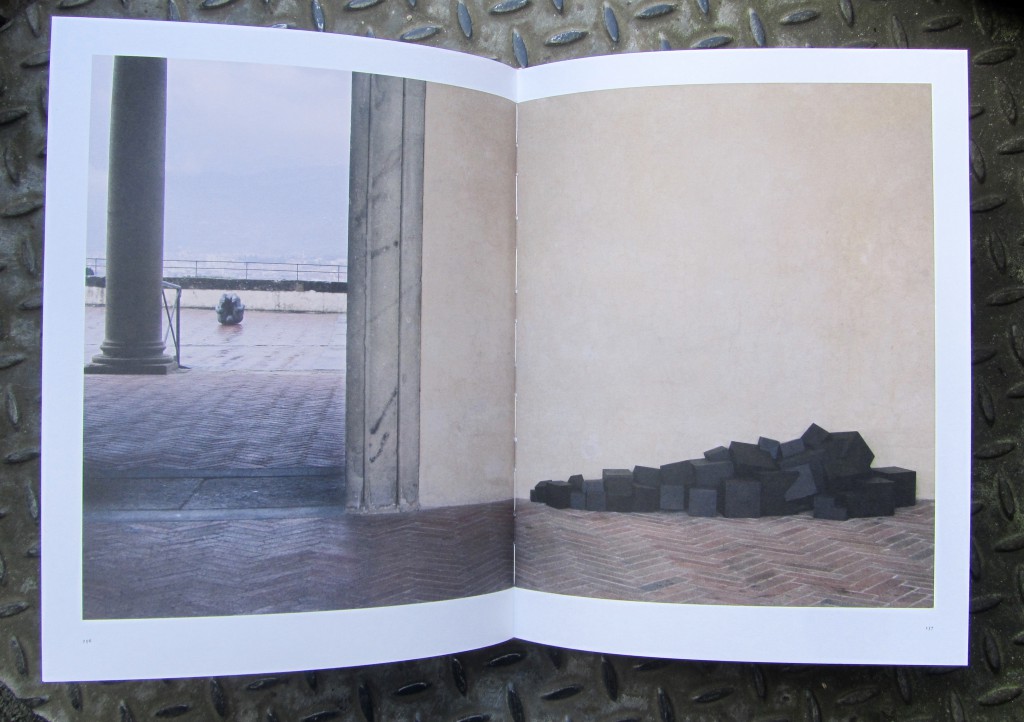

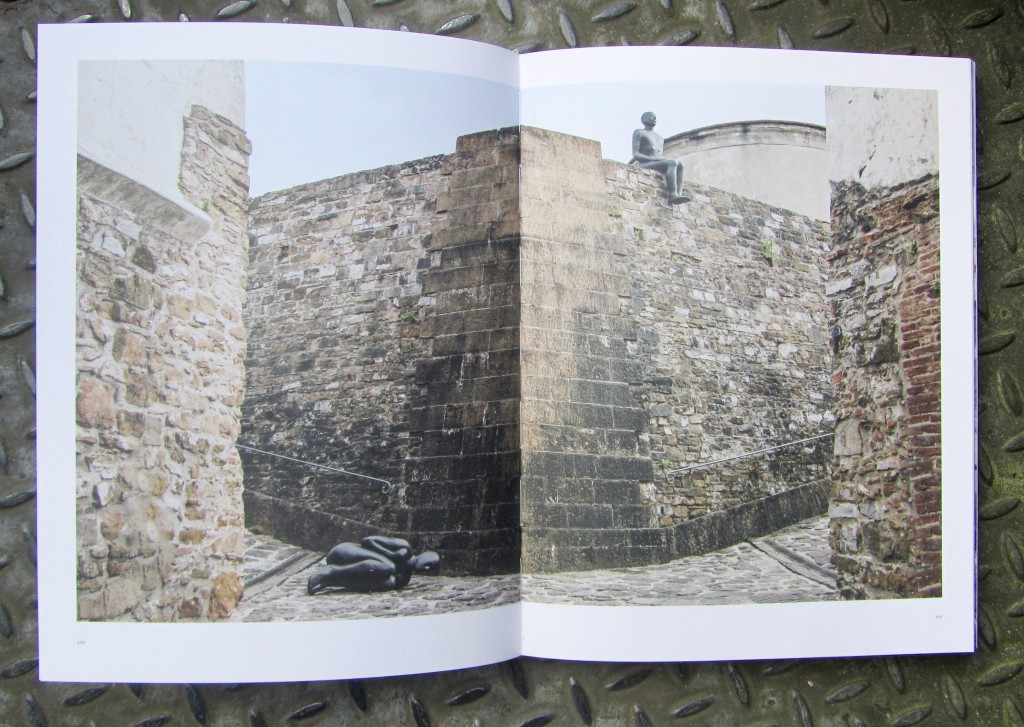

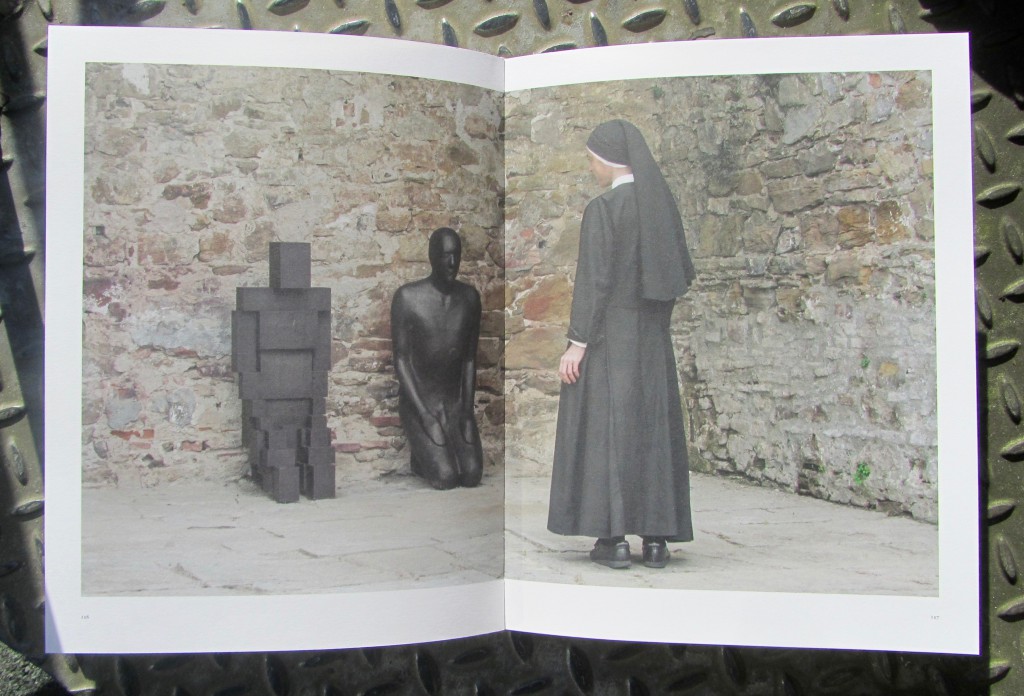

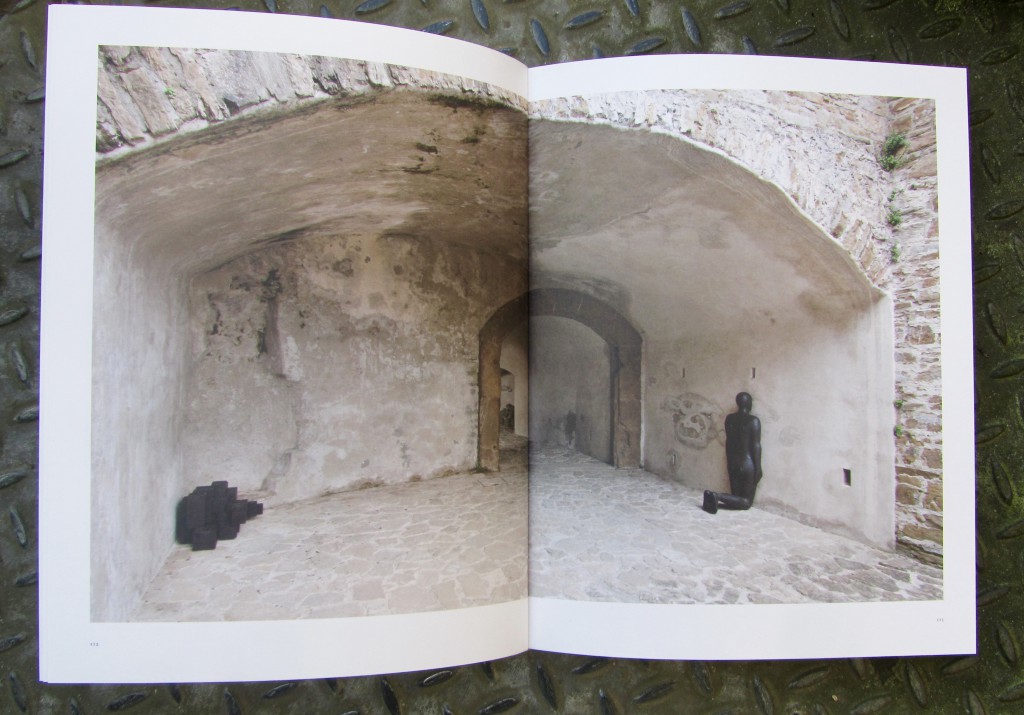

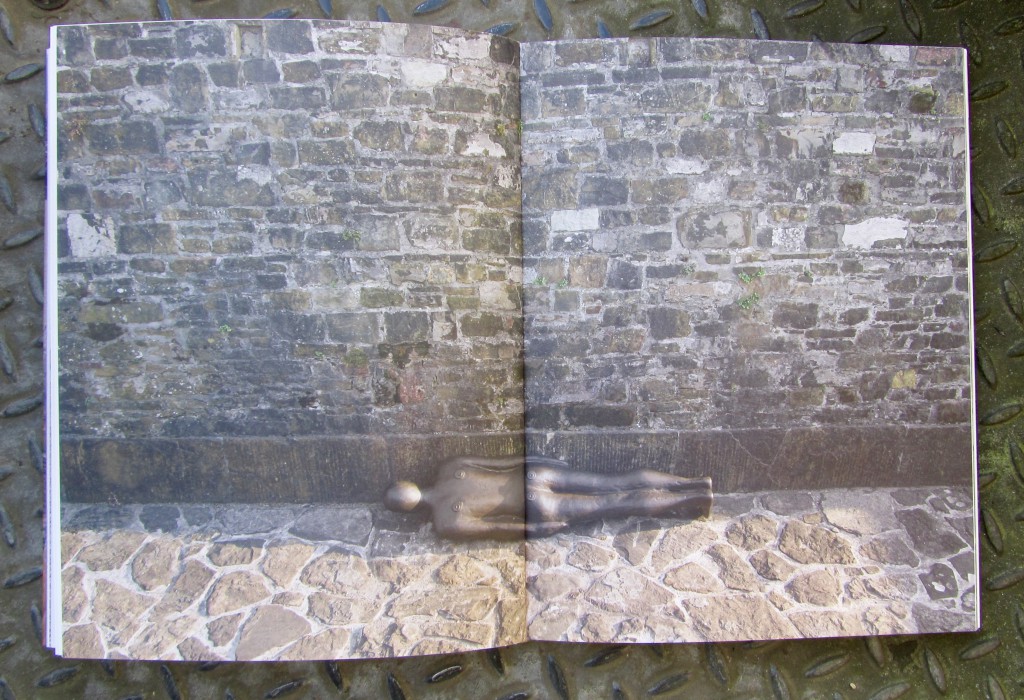

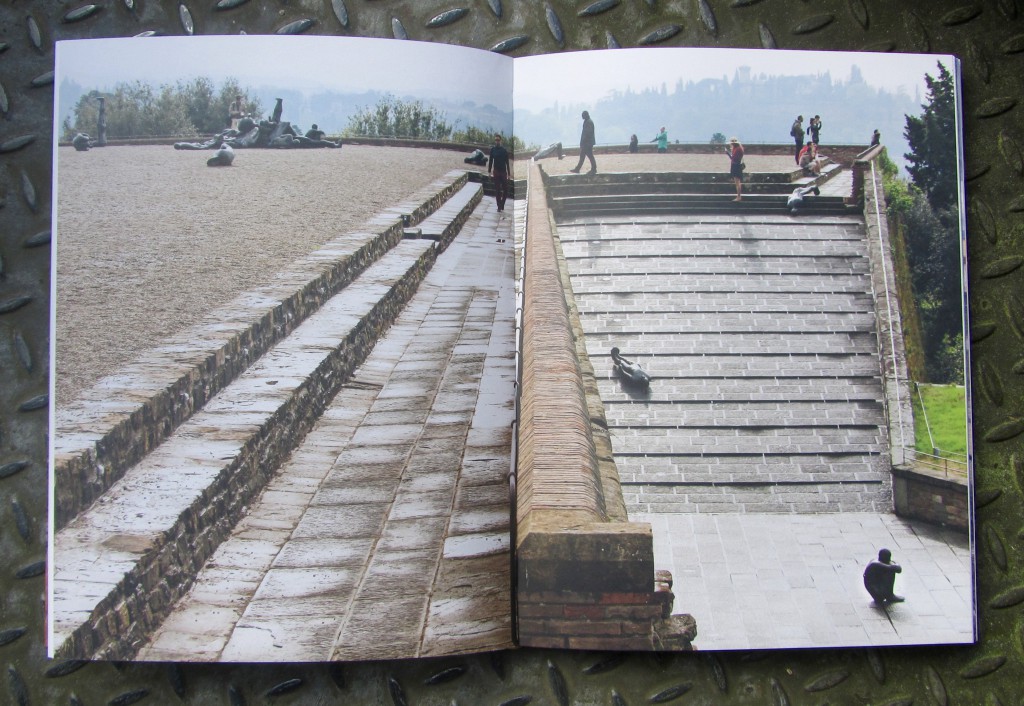

Bodycasts of the artist littered the precincts of the Forte. Some were strategically placed and others seemed more haphazard. Like the shed skins of a transforming ghost. Existential shells. And others like pixilated apparitions. Together they occupied all the various spaces of the fortifications.

I think Antony Gormley must have had a lot of fun choosing how and where to place them. They’re tokens of himself transformed as an Everyman, beautifully framed by the Renaissance architecture.

Antony Gormley exhibition HUMAN at Forte di Belvedere

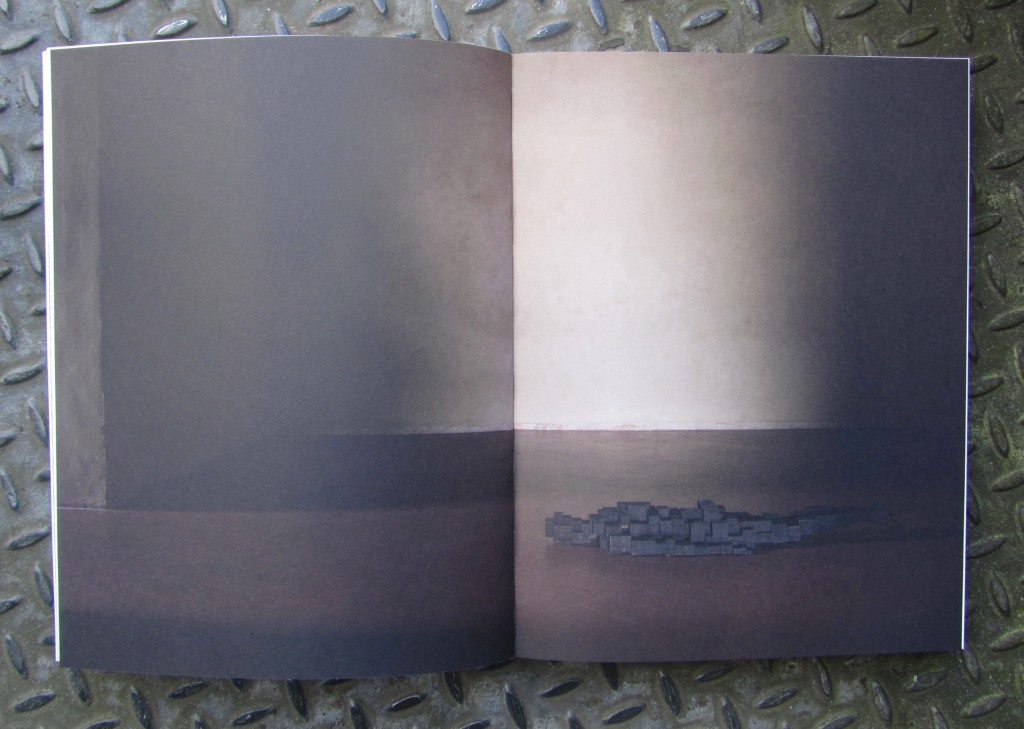

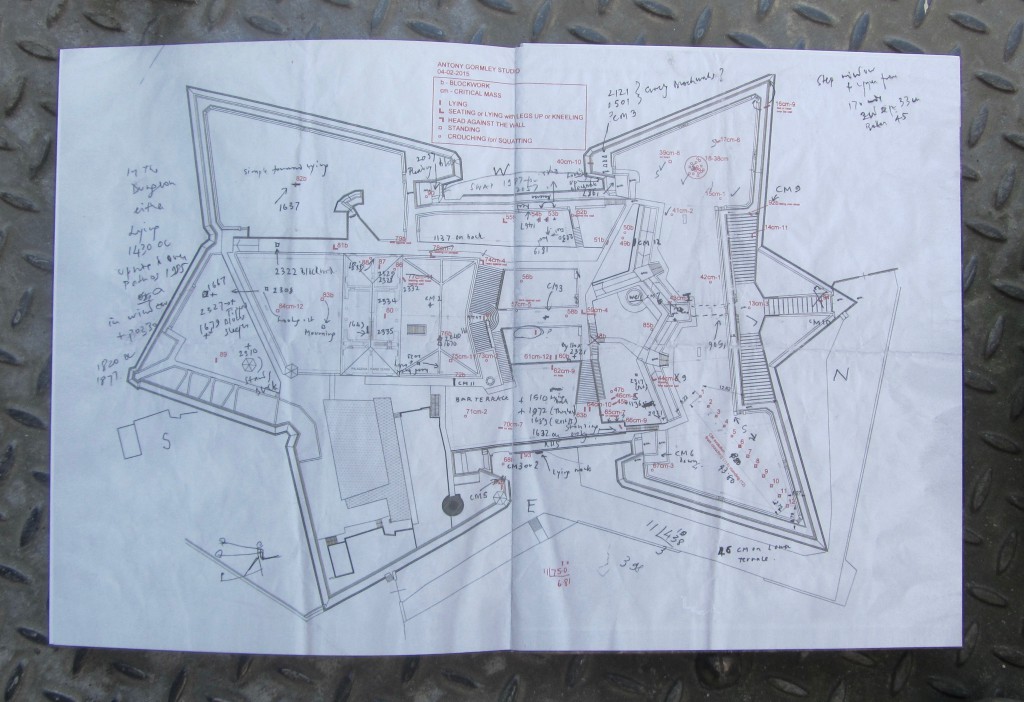

In the Palazzina at the centre of the Forte we found an exhibition catalogue.

Gormley’s ‘Blockwork’ figures are midway between the spatial fragmentation of the Cubists and the pixelisation of our contemporary media universe.

Mario Codognato, p102

Of these figures, these forms, some would seem to be male, others yet to be determined. Some are cast from a mould taken from life. Others are comprised of cast blocks which articulate the space that the body once occupied, digitally scanned from life and then articulated together as human form. Some are simply on their own. They lie on the ground. Or they are hunched in a corner. They lean against a wall. Each position is fixed. And yet, each position is contingent. The rooms, the passageways, the locales in which these singular bodies are found, are all charged.

Andrew Benjamin, p45

Walking along the terraces and around the villa we come up against a host of iron figures which the artist has placed one by one in a sensitive, careful interpretation of the architecture: of the perimeter planes, of the vanishing points and horizons. This is a process that he refers to as ‘acupuncture’.

Sergio Risaliti, p10

With its fortress rising up over the Boboli Gardens, Florence is, for Gormley, the perfect setting for showing his distrust for the age of Lorenzo the Magnificent and Cosimo I. By occupying every inch of the space, he reminds us that the centuries of Renaissance magnificence were also dominated by forces hostile to the dignity of man, and that the ‘Princes’ of the Medici era were actually capable of the darkest violence, calculated persecution and discrimination.

Sergio Risaliti, p10

I am very intensely aware of the failure of Humanism.

Antony Gormley, p34

The deep interest you have in each individual, in humankind and its place in the world, is here underscored even in the title of the exhibition itself, “Human”. In this ‘occupation’ of the fortress by ‘humans’ – human forms presented in a variety of situations and predicaments – a projection of the diversity of humanity materialises.

Arabella Natalini, p26

Humankind, or rather the human condition, is the mainstay of his aesthetic and conceptual research. In an epoch in which mankind is no longer the fulcrum of the universe, but rather a disoriented, phantasmal being, and a simulacrum of apparitions, Gormley tries to convey different states of mind without giving answers but by posing questions.

Mario Codognato, p89

what would I do without this world faceless incurious

where to be lasts but an instant where every instant

spills in the void the ignorance of having been

without this wave where in the end

body and shadow together are engulfed

what would I do without this silence where the murmurs die

the pantings the frenzies toward succour towards love

without this sky that soars

above its ballast dust

what would I do what I did yesterday and the day before

peering out of my deadlight looking for another

wandering like me eddying far from all living

in a convulsive space

among the voices voiceless

that throng my hiddenness

Samuel Beckett, p89

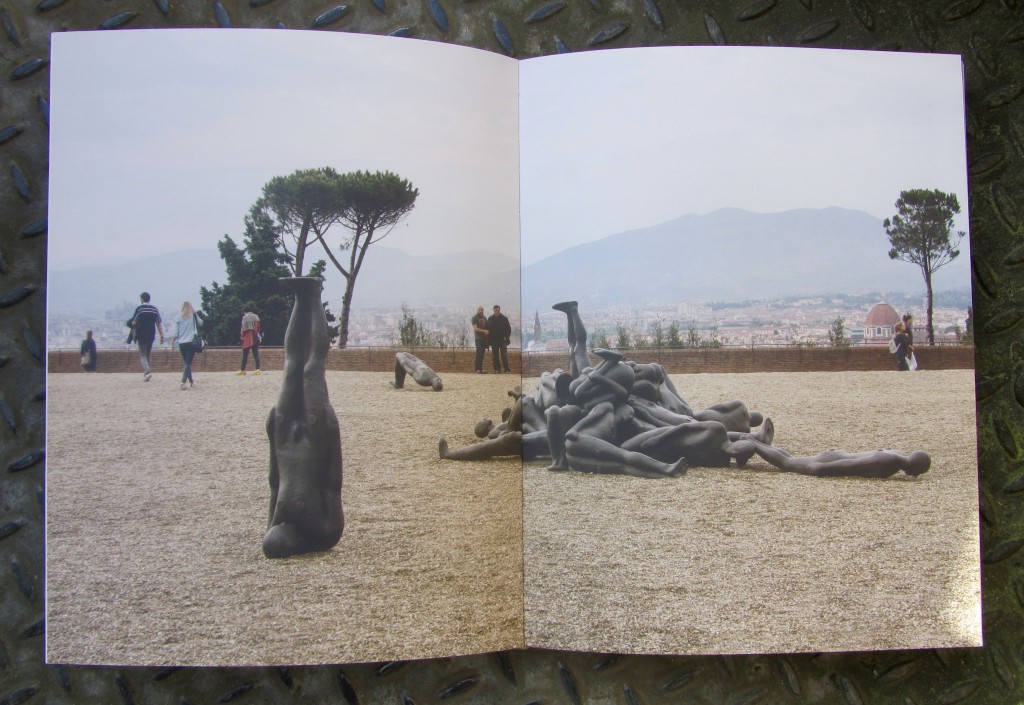

When we look at the line of sculptures that Gormley has arranged along the north-east bastions of the Forte di Belvedere, we are prompted to judge the evolutionary process of our species… The first figure in this sequence is huddled up in a primordial egg, and appears to be emerging into life, looking towards the earth and seemingly perceiving itself as one with the Great Mother. The last figure, on the other hand, is firmly erect, with its eyes towards the sky… When faced with each of these anthropomorphic sculptures, we are able to revive a sacral relationship with Mother Earth, in an anthropological, scientific and poetic sense, rejecting any titanism or heroism of a religious or technological nature.

Sergio Risaliti, p14

HUMAN, FORTE DI BELVEDERE, FLORENCE, ITALY, 2015

The Forte di Belvedere, its function as defensive fortress and its expression of temporal power are the basis of this exhibition. Overlooking Florence, a city that typifies an urban ideal, this site offers a place in which to consider how architecture serves to shelter, protect and dominate people and space.

The Forte is an extraordinary example of a terraforming: a natural hill transformed by Ferdinando de’Medici into an artefact. It has a long association with contemporary art and has often been used as a monumental context for monumental sculptures. Rather than attempt to insert works that try to match the scale of the site, I have chosen to exhibit works that are life-size and that will allow the mass and form of this remarkable construction to speak.

At the core of the exhibition there are two arrangements of the work CRITICAL MASS II (1995). This work comprises twelve body forms, each cast five times to produce a total number of sixty works that can exist in any orientation. CRITICAL MASS II identifies a number of basic body postures from the contemplative to the supplicant, from the mourning to the deferential, from the position of a man who awaits an order to the dreamer. On the east side of lower terrace of the Forte the twelve body forms of CRITICAL MASS II are installed in a linear progression, from foetal to stargazing, recalling the ‘ascent of man’. On the opposite side is a jumbled pile of the same bodies. Here, as abandoned manufactured iron objects, each ten times the specific gravity of a living human body, they reflect the shadow side of any idea of human progress, confronting the viewer with an image redolent of the conflict of the past century.

This dialectic between aspirational and abject is the tension that runs throughout the exhibition.

As the installation infiltrates the spaces and places of the Forte, a dialogue between anatomy and architecture evolves. Bodyforms become increasingly rectilinear, departing from the symmetry of the CRITICAL MASS II works to the more cubic and chaotic forms of the Blockworks. A single work installed against the wall in an entrance tunnel to the east connects building and body but also underlines the contrast between the idealism of a Renaissance city and the figure that we all know well, that of the homeless person sheltering in a city doorway.

On the top terrace, outside the loggia, a mourning figure from CRITICAL MASS II faces a horizontal plane that it shares with a Blockwork that looks out to the campagna. At the heart of the exhibition, in the old gunpowder store, is a single sculpture constructed from pure cubes, where the idealisation of the statue placed on a plinth is replaced by the pathos of the exposed prisoner on a box.

The concept behind the exhibition is to open up the Forte through sculptural acupuncture: the works are widely dispersed to catalyse the inherent masses, constrictions and panoramas that the site affords. In finding the right places to make these confrontations and allusions, I want to create stumbling blocks that stop the viewer in their tracks. I want to encourage the viewer to think again about who they are and how they negotiate the spaces around them.

Antony Gormley, February 2015

Musei Civici Fiorentini / Forte di Belvedere

One thought on “Forte Di Belvedere”