Karen had just finished reading Wilding and was recommending it to everyone, saying it was the best book she’d read in ages. It’s the story of an experiment to rewild a West Sussex farm, restoring the land and its wildlife. It’s written by Isabella Tree who, together with her husband Charlie Burrell, is the owner of the Knepp Wildland Project. Dominic said he’d visited Knepp Castle many years ago, so as a surprise, whilst he was away in Spain, we arranged a works outing for when he returned.

It was the last day of summer when we drove down for a guided tour of Knepp. But before we arrived for our appointment, I took us on a detour up to the castle. I wanted to meet the ancient oak tree that features in the opening chapter of the book.

Ted Green came to a standstill under the canopy of the old oak. He caressed the rippled bark with a weather-worn hand. ‘You’re a sight for sore eyes,’ he said. As if in response a stirring shuffled through the foliage above our heads and a smattering of acorns thudded to the ground. Handing Charlie one end of a ‘Diameter at Breast Height’ measure, Ted extended the tape around the trunk and with a cry of delight read off 7m. Its girth made it about 550 years old. Most likely, it had started life during the War of the Roses, nearly three centuries before my husband’s family, the Burrells, had arrived at Knepp. It would have germinated when ‘Knap’ was a thousand-acre deer park owned by the Dukes of Norfolk, its acorns fodder – or ‘pannage’ – for wild boar and fallow deer. As a fine young tree only a hundred years old, it would have welcomed the arrival of the Carylls, Catholic ironmasters, owners of Knepp for over a hundred and seventy years. In the mid-seventeenth century it would have witnessed the Civil War, the assault on Knepp by Parliamentary troops and counter-assaults by Royalists. It had lived and breathed what we can only absorb from history books.

Meanwhile three red deer stags tried blending in with the branches of a fallen tree.

We left the park and continued down the road to the Countryman Inn at Shipley for lunch.

Afterwards, approaching our rendezvous, we passed these curious poles with sticks on top.

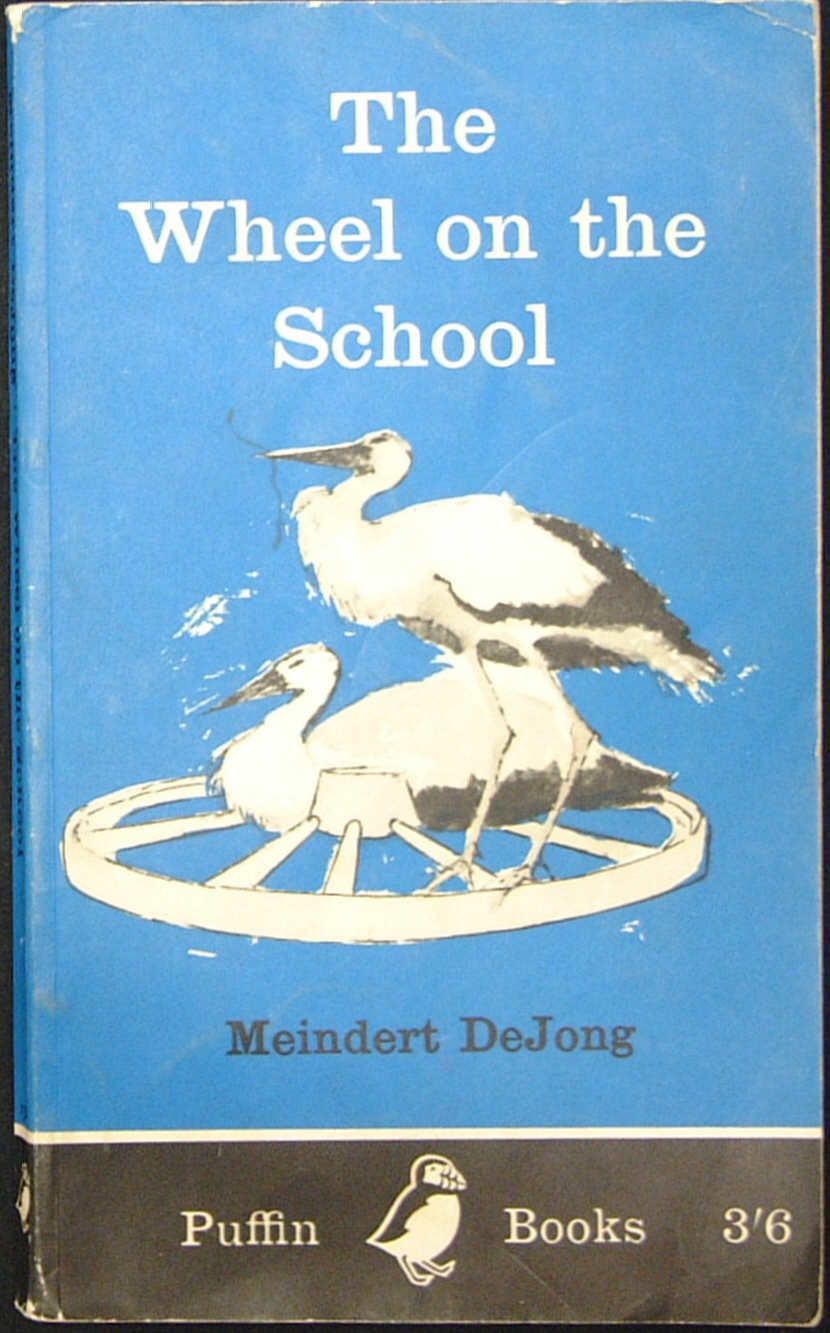

I was reminded of The Wheel on the School and how the Dutch schoolchildren were determined to put wagon wheels on the rooftops to encourage the storks to build their nests there. It was said to bring good luck. And we later learned that was also the plan at Knepp, to reintroduce storks which had once been so common hereabouts that the nearby village of Storrington was named after them.

Our tour of the Knepp Castle Estate Wildland Project was to be around the Southern Block.

We arrived to find Lucy, our guide, greatly excited, having just witnessed a stoat take down a rabbit directly below her window. We went to look but the stoat had dragged the rabbit safely out of sight.

As we left the farmyard and walked down by Newbarn Pond the sky was busy with house martins darting and chirping and kissing midair, the young birds being fed inflight meals by attentive adults.

Yurts in the glamping field

Tunnel in a blackthorn hedge

Birdsong

I’d made enquiries earlier to ask if there were any particularly notable or ancient trees at Knepp, and I’d been referred to the Ancient Tree Inventory. But I’d been told to look out for one old oak that is host to a very rare bracket fungus. I think maybe this is the tree, although it was not looking its best.

There’d been strong winds the night before and a large part of the tree had been blown down.

But the rare bracket fungus was still in place. Was it the cause of the tree’s collapse?

Woodpeckers had nested here and little owl chicks had been seen in the base of the tree.

If left where they lay would the fallen branches be stripped by the deer and the pigs and the cattle? The aim at Knepp is to let the land revert to its prehistoric roots with as little human interference as possible, so perhaps they would stay where they fell until the fallen branches were consumed by nature. It is hoped that the grazing animals will create new habitats and restore wildlife to Knepp.

It’s not a spectacular landscape, the ragwort and fleabane and brambles are not particularly photogenic, but it’s the next stage in a story that began in 2000 with an inspirational visit to the Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands, ‘one of the most extraordinary and controversial nature reserves in the world’.

Open up the box, allow natural processes to develop, give species a wider scope to express themselves, and you get a very different picture. This is what the Oostvaardersplassen is about. Minimal intervention. Letting nature reveal herself. And the result is an environment we know nothing about… We realised something important early on in the establishment of the reserve, that there’s a fundamental process we haven’t accounted for in nature, something that doesn’t get a chance to express itself when humans are in control: the influence of animals. Animals are drivers of habitat creation, the impetus behind biodiversity. Without them, you have impoverished, static, monotonous habitats with declining species. It’s the reason so many of our efforts at conservation are failing… In effect, could we manage this land for nature not by costly human intervention, but using natural processes, with grazing animals as the drivers?… So what we’ve shown in the Oostvaardersplassen is that a mix of herbivores, allowed to express themselves freely, without human control, stimulates a much greater variety of animal and plant species than can be found on the short grassland characteristic of seasonal farmland grazing…

Acorns that fall from the oak rarely produce new trees, but those that are distributed by jays stand a better chance. Lucy pointed out a struggling oak sapling nearby, its young leaves nibbled by grazing animals, and another that had grown in the shelter of a bramble bush that was thriving and was a living demonstration of the New Forest saying that ‘the thorn is the mother of the oak’.

And then, by a nice coincidence, just as I’m writing about acorns and jays, a perfectly timed tweet appears from Robert Macfarlane:

Words of the day: “Scréachóg Choille” – lit. ‘Screecher of the Woods’; Irish name for the jay. The jay’s scientific name is Garrulus glandarius, meaning Babbler of the Acorns. A single jay can cache up to 5000 acorns in an autumn, hiding them in tree-bark, earth, leaf-litter.

Rosehips

I spy Kai

Kai spies Pig

The Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976 prohibits the introduction of wild boar into the project, so our Tamworth pigs have taken on the role of their indigenous forebear. An old breed, renowned for their hardiness, they have long legs and snouts, narrow backs, long bristles and a surprising ability to sprint for short distances as fast as a horse – very much like the wild boar.

A windswept spindle tree

Pig rootled turf – in search of roots and rhizomes, earthworms and other invertebrates.

Then suddenly, in the distance, between the trees, a red deer looks back at us.

Red deer are indigenous to Britain but, in the wild, they have been relegated, almost exclusively, to the Scottish Highlands and we have come to think of them as an animal whose natural habitat is the landscape of Landseer – barren uplands swathed in mist. This was not always so, as their behaviour at Knepp demonstrates. They love wallowing in rivers and ponds and, in the warmer, lusher environment here, they grow almost twice the size of Scottish beasts and develop colossal antlers. Red deer, it is now believed, were originally a riverine species that were pushed out of their preferred habitat throughout Europe as humans took over the fertile floodplains and river deltas.

A green lane

Dominic and oak tree

Thinking about tree climbing

The view from the tree. There’s a green sandpiper down there, just visible through binoculars.

Then in the distance we caught a brief sight of a couple of longhorn cattle disappearing into a hollow.

We didn’t follow, fully expecting them to re-emerge before too long, but we never saw them again.

Here’s a photo of two I saw earlier in Epping Forest.

Longhorn cattle are commonly used in naturalistic grazing projects, acting, in effect, as proxies for their extinct ancestor, the aurochs. Hardy, traditional breeds retain the ability to survive outside all year round. Like their ancestors, they browse on vegetation as well as graze – crucial for the winter months when good grass is scarce.

We stopped for refreshment at an old field barn (tea, coffee, elderflower cordial) and when I asked about the nesting box in the roof and the pile of droppings on the barn floor below, Lucy was quick to explain about barn owl pellets. Afterwards I asked for a few words to remind us of what we’d seen…

As a conservation biologist with a specialty in mammals looking at animal droppings is a regular occurrence, you can tell an awful lot about what the animal has been eating. One particular favourite of mine is looking at owl pellets. Owls digest their food differently, they will swallow their prey whole, or rip it into manageable chunks, including all the fur and bones. This food goes into their gizzard, all of the soft squishy bits go to their stomach for digestion and pass through, all of the indigestible bits get compacted together in the gizzard and coughed up as a pellet. The owl will cough up 1 or 2 pellets a night and it takes roughly 6 hours for a pellet to form. Barn owls in particular have a very low acid so the bones are really well preserved, this means they are fantastic for monitoring the small mammals in the area as you can identify the bones to species level. Each pellet can contain the remains of 4-5 small mammals and regularly contain field voles, bank voles, wood mice and shrews. Identifying the mammals inside is done by skull shape and the shape and size of the teeth on the jaw bones. If I can remember correctly the pellets that we collected and looked at mainly contained Bank vole remains, the shape of the teeth creates a rounded zigzag if you look from the top of them. You can also see the other bones in the pellet including shoulder blades, hip bones and even the ribs!

The sweetest blackberries we ever tasted

Left to right: Dominic, Karen, Kai, Chris, Lucy.

Hammer Pond

Fox scat and private sign – two territorial markers

Sweat wasp nest hole

Another Tamworth pig

And another

Cissbury Ring on the far hilltop

Knepp was a revelation, and a beacon of hope. In these dark days when our planet’s future seems increasingly in jeopardy, when one day the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change tell us we have just twelve years left to limit global warming, and then the next day scientists warn us that we are cutting down the tree of life, when we feel helpless in the face of a terminal meltdown and wonder what on earth we can do, we find these people at Knepp are already doing it.

A Knepp butterfly

It was becoming clear to Charlie and me that had we set out with the intention of creating the perfect habitat for purple emperors, we would never have achieved the numbers that have spontaneously emerged through rewilding. The phenomenon is an example of what we are learning to refer to as ’emergent properties’. An emergent property is a property which a complex system has, but which the individual constituents of that system do not have, like the cells of a heart which, on their own, do not have the property of pumping blood but which together create a higher level aggregate – a complex organ – that does. At Knepp, previously missing or dormant components were coming together, striking up extraordinary and unexpected outcomes. In effect, two plus two was making five – or more; and this imposed on us, as midwives of the system, acceptance and humility about our role. There may well be other factors involved in the success of purple emperors at Knepp that we have not yet identified, perhaps may never identify – a preference for certain types of animal dung, minerals or sap-runs, temperatures, moisture or some other tiny cog in the wheel, or a fortuitous combination of any number of things. What seems imperative is that we take care not to fall into the trap of assuming, as conservationists have so often in the past, that a couple of specifics – some tall trees and a massive amount of sallows – is basically all the purple emperor needs. This is tantamount to asserting that the individual cell of a heart has the property of pumping blood – an assumption known as the ‘fallacy of division’. The purple emperor butterfly, with its complicated life cycle involving numerous stages requiring different conditions over the course of almost a year, beats its wings to the tune of the entire symphony orchestra that has conjured it into being.

※

Rewilding Knepp

※