On holiday in Italy last year, we were surprised and amazed by the supermarket tomatoes, so different to the usual British varieties. Now, with holiday season approaching again, I was looking back through our photos, and this one was pretty much the first I took. And then I discovered there were lots more that I’d overlooked, so here are a few of the freshest and ripest.

We arrived in Siena by escalator from the carpark below the Basilica of San Francesco.

This is the view looking back through the gate into the Piazza San Francesco.

On Via dei Rossi.

Our first sight of the remarkable Torre del Mangia, the giant bell tower of the Palazzo Pubblico.

Panorama from Costa Barbieri.

Piazza del Campo

Steep alleys lead down from the main streets of the town, Via di Città and Via Banchi di Sotto, to the Campo, the main piazza of Siena, with its extraordinary shape in the form of a fan or scallop shell, which slopes gently down to the magnificent Palazzo Pubblico with its incredibly tall tower on the flat southeast side. This has been the centre of civic life since it was laid out in the 12th century, and it was first paved in red brick and marble in 1327-49 (on quiet days in winter stonemasons can sometimes be seen sitting here carefully renewing by hand the herringbone bricks or stone courses, with low basketwork screens in front of them to catch the splinters). The comparatively low picturesque buildings which follow its curve, mostly with restaurants or cafés on their ground floors, allow ample sunlight into the square, and its life moves in and out of the shadows at different times of day according to the season, since almost the entire area is reserved for those on foot. The huge Fonte Gaia is a free copy made in 1858 by Tito Sarrocchi of the famous original fountain by Jacopo della Quercia. This was the main fountain in Siena, at the centre of the system of underground aqueducts which provided water for the citizens, and it still has two little fountains which provide a constant stream of drinking water.

Inside the Palazzo Pubblico.

The Palazzo Pubblico serves as the town hall, but the state rooms are open to the public. The main council chamber is called the Sala del Mappamondo, after a map of the world painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the early 1300s. One wall is covered by Simone Martini’s ‘Maestà’ (Virgin in Majesty). Painted in 1315, it depicts a beautiful Madonna seated beneath a baldacchino borne by apostles and surrounded by angels and saints.

On the opposite wall is the famous fresco of ‘Guidoriccio da Fogliano’, captain of the Sienese army, setting out for the victorious siege of Montemassi. It is a delightful work (partly repainted), traditionally attributed to Simone Martini (1330). Since 1977 it has been the subject of a heated debate among art historians, some of whom suggest it may be a later 14th-century work, and therefore no longer attributable to Simone Martini. The fresco beneath, discovered in 1980, and thought to date from 1315-20, which represents the deliverance of a ‘borgo’ (with the castle of Giuncarico) to a representative of the Sienese Republic has been variously attributed to Duccio di Buoninsegna, Pietro Lorenzetti or Memmo di Filippuccio (Simone Martini’s master). The outline of a circular composition here is thought to mark the position of the lost fresco of the Sienese territories, painted in 1345 by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, which gave its name to the room (‘Mappamondo’). It may have been meant to rotate (hence the hole at the centre of the circle); one of the theories (many of them fanciful) that have been advanced in connection with this work is that Giudoriccio was placed above the circle in such a way that his horse’s hooves would seem to gallop through Siena and her dominions as the map turned.

In the Sala della Pace (Room of Peace) the walls are covered with frescoes from 1338 by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, “considered the most important cycle of medieval secular paintings remaining in Italy.” The two photos above together show the entrance wall and The Allegory of Good Government.

…with its effects in the town and countryside: shopkeepers plying their trade, women riding safely through the streets, young people making music, fine buildings in good repair, and man and beast working in harmony in fertile countryside. The city naturally represents Siena.

We went looking for the Natural History Museum of the Academia degli Fisiocritici, described in the guide book as having “the atmosphere of a wunderkammer”, but sadly we failed to find it (this is not my photo). We lost ourselves on Via San Pietro. In retrospect I now see that if we’d continued a little further we would have arrived here. Instead we found ourselves at the gate to the Piazza del Duomo.

Siena Duomo (1136-1382) is one of the most spectacular in Italy… Its style is an amazing conglomeration of Romanesque and Gothic, delineated by bands of black and white marble, an idea adapted from Pisa and Lucca – though here with much bolder and more extravagant effect. The lower part of the facade was designed by the Pisan sculptor Giovanni Pisano, who from 1284 to 1296 created, with his workshop, much of its statuary – the philosophers, patriarchs and prophets, now removed to the Museo dell’Opera and replaced by copies.

Rough Guide to Tuscany & Umbria

But the queue to get in was endless. We were hungry and thirsty and the thought of standing for hours in the hot August sun was not appealing. So we turned and entered the cool interior of the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala.

Opposite the duomo is the irregular Gothic facade (modified over the centuries) of the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala, a hospital founded in the 9th century for pilgrims travelling down the Via Francigena on their way to Rome (the oldest document to have survived which mentions the hospital dates from 1090). The name comes from its position in front of the steps (scala) which lead up to the duomo, and its emblem is a step-ladder which can still often be seen on numerous buildings in Tuscany which it came to own. It was at first administered by the duomo, but after 1195 became progressively a lay institution. Up until a few years ago it was still a hospital, but this has now moved, and the huge group of buildings is slowly being restored as a cultural centre and museum (the Pinacoteca will one day be transferred here). Only a small part is as yet open to the public, but in the next few years more and more will become accessible.

AS YOU ARE I WAS

AS I AM YOU WILL BE

It was a collection of spaces and atmospheres, finished and unfinished, a work in progress, furnished with temporary exhibits amidst the exposed skeleton of the ancient hospital. We wandered from room to room over many levels. The ground floor was 4° Livello, but gradually as we descended the stink of the sewers grew stronger and stronger. 1° Livello was in the bowels of the building.

There was much to see but it was not possible to remain down there for long.

Back above ground the air smelled sweeter and there were Winter Flowers by Francesco Clemente.

Francesco Clemente: Fiori d’inverno a New York

This exhibition is an act of homage on the part of Francesco Clemente to Siena, the city that in 2012 paid him the compliment of commissioning from him the banner or ‘Palio’ awarded to the winner of the famous bareback horse race.

Ten original works are here presented for the first time. The Fiori d’inverno a New York (Winter Flowers in New York City) series was created together with the artist’s wife, Alba Primiceri, and consists of five canvases with representations of large-scale flowers, which took the artist six years to produce (2010–2016). Certain flowers found in the winter months in New York were chosen as the basis for these pictorial elaborations, which are distinguished for the careful selection of vegetable pigments and for their slow execution in several phases. The theme of Winter Flowers is a meditation on old age, and on the irreducible joy that can characterise this stage of life.

Tree of Life

The cycle of the Tree of Life, painted between 2013 and 2014, represents on the other hand the summation of the “emblematic” style adopted by Clemente for some of the motifs present in his work since the 1970s and linked to the cycle of life, such as the Tree, the Boat, the Bridge and the Wheel.

Clemente’s iconography freely draws on the most varied sources such as classical mythology, Buddhism, oriental history and literature and the contemporary imagination, but it clearly reveals his interest in the contemplative traditions of India, a country where the artist lived for long periods from the early Seventies and where he continues to spend many months of the year.

Love

Orientation

For Morton Feldman

Wheel of Fortune

Out in the piazza we marvelled at the Duomo and its liquorice-striped bell tower.

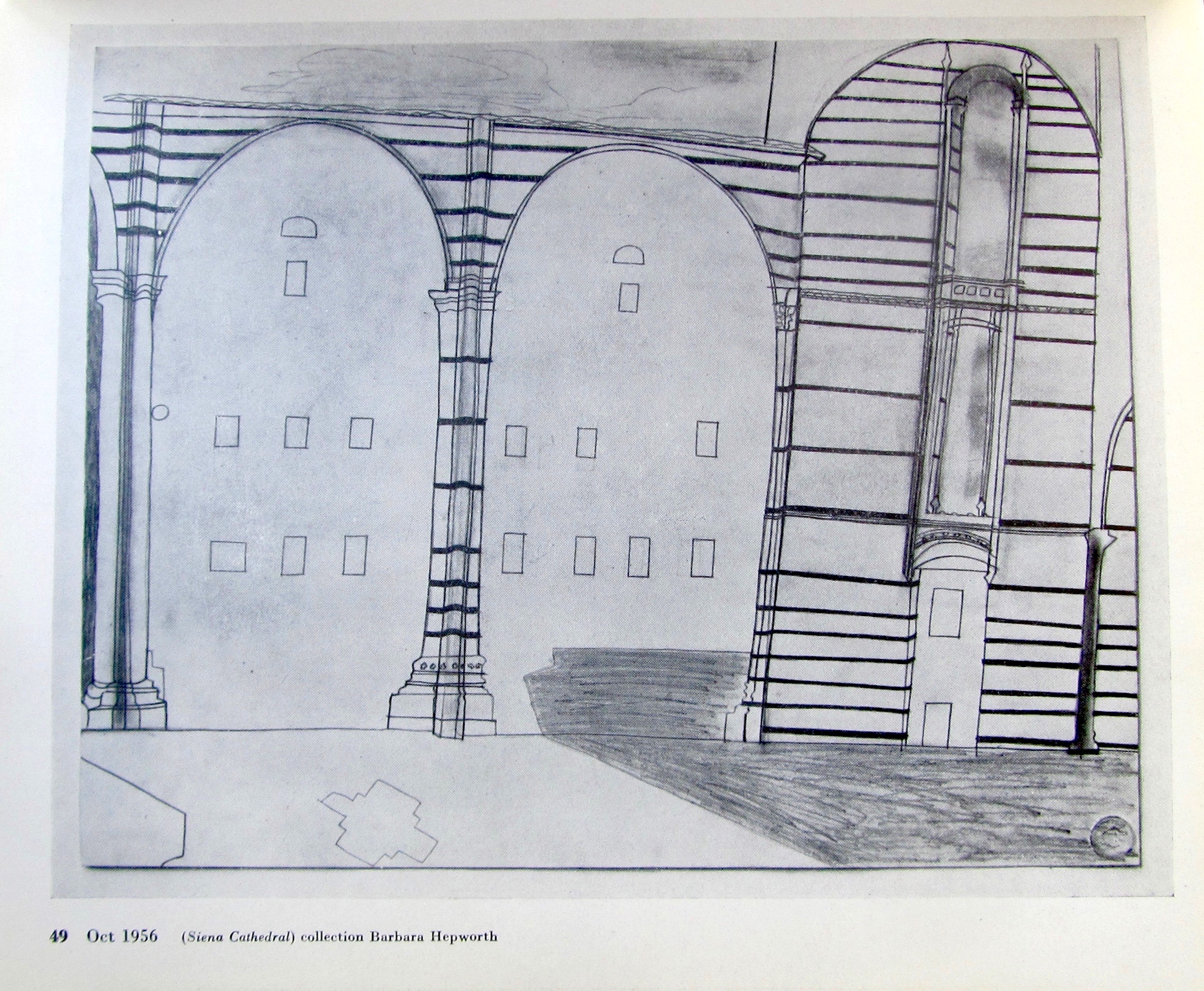

I remembered Ben Nicholson and I wished I’d brought my sketchbook.

May 1957 – Campanile, Siena: Ben Nicholson

1966, Siena: Ben Nicholson

A poster for a viola recital by Kim Kashkashian and I wished we’d bought tickets.

We came back into the Campo down a side street only to find the way was blocked by tiers of temporary grandstand seating for the Corsa del Palio, the bareback horse race first recorded in 1283.

Every year ten of the seventeen ‘contrade’, or city wards, are selected to compete in the famous Corsa del Palio, a horse race which takes place in the Campo twice a year: on 2nd July (Visitation) and 16th August (the day after the Assumption). It is watched by some 30,000 people who crowd into the Campo itself. The strong rivalry between the ‘contrade’ provides an extraordinary atmosphere of excitement in the city throughout the summer. The prize is the ‘palio’, a banner designed anew each year, which goes to the winning ‘contrada’ (not to an individual). Celebrations continue for many weeks after the victory.

Three days before the race, the horses are drawn by lot by each contrada. Jockeys are chosen and paid for in advance. There are six dress rehearsals, the last one, the ‘provaccia’, on the morning of the race. At 2.30 or 3 the horse and jockey are blessed in the oratory of each ‘contrada’: everyone is invited to keep silent, and flash photography forbidden in order not to startle the horse; only when it is well outside the oratory does the cheering and singing erupt. At 4.30 or 5 in Piazza del Duomo a parade forms, led by the dignitaries of Siena and members of each ‘contrada’ in Renaissance costume. It proceeds round the Campo to the accompaniment of the tolling bell from the Torre del Mangia, and with two flag-throwers performing the ‘sbandierata’ for each ‘contrada’. At the end of the procession a triumphal chariot drawn by four white oxen bearing the ‘palio’, with eight buglers, enters the Campo from Casato di Sotto, ringing a bell. The crowd salutes it by waving little flags at it as it passes. The ‘palio’ is hung up at the corner of the Campo near Via dei Pellegrini (beside the starting posts).

The horses and jockeys (riding bareback) enter from the courtyard of Palazzo Pubblico, lining up behind a rope. Another horse (drawn by lot) canters up from behind: when he is level with the rope, the ‘mossiere’ (or race official) lets the rope fall so that they all start together (‘la mossa’). The timing is extremely difficult, and there are usually a number of false starts (which are signalled by a loud cannon shot which recalls the jockeys to the starting point). It can take over half an hour to start the race (after three false starts the order of horses is changed), and since his decision is often contested, the ‘mossier’ is rushed out of the Campo as soon as the race finally starts. It consists of just three laps of the Campo, and is all over in just a few minutes. It is the horse that wins, not the jockey, so even if a horse comes in riderless, victory can be claimed.

Celebrations by the winning ‘contrada’ last all night (and the horse eats at the head of the table at the banquet held in its honour). The following morning the captain, flag-throwers, drummers and horse of the winning ‘contrada’ parade around the city with the ‘palio’, visiting the headquarters of each ‘contrada’ (except that of their traditional enemies). The banner of the winning ‘contrada’ is flown from Palazzo Pubblicco. There has been criticism that the Palio is too dangerous, but in recent years there have been no fatal accidents, and greater care is taken to select horses hardy enough to endure the course and the strain of the excitement.

The Parade of the Contrade, Piazza del Campo, Siena: Vincenzo Rustici

Twice a year the Italian city of Siena goes crazy for the oldest horse race in the world: the Palio. Not your average race: strategy, bribery and corruption play as much a part as the skill of the riders. Horses are allocated by lot four days prior to the race. This is when the madness truly begins. In the eye of the storm stand the jockeys. Loved and loathed by the districts they represent, they forge alliances and make deals promising large cash sums to try and get the best start. Legendary rider Gigi Bruschelli has won 13 Palios in 16 years and is accused by his critics of monopolizing the race. He works the system, paying off younger jockeys and fixing the race with average horses. Two races away from beating the world record, Bruschelli will do anything to win. But one jockey stands in his way, his former trainee, a handsome young Sardinian, Giovanni Atzeni, who is quietly determined to challenge his old mentor. Less interested in bribes and collusion, he rides for the love of the race. PALIO is the thrilling story of a young ‘outsider’ keen to break in to the dangerous but lucrative race and the corrupt ‘insider’ who has manipulated the city of Siena for a decade. Their passionate and dramatic battle is an epic and cinematic tale of Italian life in microcosm.

In preparation for our holiday it seemed like a good idea to watch this movie beforehand as a piece of entertaining homework. But in fact I only lasted a few minutes. The sight of terrorised horses smashing into barricades was enough for me to switch off. It seemed a brutal display of inhumanity, an adrenalin fuelled stampede around a baying crowd of corralled spectators. I was in no hurry to visit Siena. And once there, all the implied violence of those barricades has coloured my view of the city.

We left quietly, around the backstreets, avoiding the crowds and found our way back to the church of San Francesco where we’d entered Siena and we paused in its cool tranquil cloisters before leaving.

※

Palazzo Pubblicco / Duomo di Siena / Santa Maria della Scala